An Exciting Collaboration Between Two Giants of Chicago's Arts Scene

Daniel Hautzinger

January 16, 2019

Great Performances broadcasts Orphée et Eurydice from Lyric Opera of Chicago on Friday, January 18 at 9:00 pm. It will be available to stream after the broadcast for a limited time.

Christoph Willibald Gluck revolutionized opera with his Orfeo ed Eurydice of 1762, instituting reforms that eventually culminated in the masterworks of Richard Wagner a century later. Now, Gluck’s opus once again marks a new beginning, as the first collaboration between two mainstays of Chicago’s arts scene: the Lyric Opera of Chicago and the Joffrey Ballet. Their production of Orphée et Eurydice (Gluck prepared a revised French version of his Italian original in the 1770s after he was brought to Paris by his former pupil Marie Antoinette), directed by the renowned choreographer and director John Neumeier, premiered in Chicago in the fall of 2017 and will be broadcast as part of Great Performances on Friday, January 18 at 9:00 pm.

“Working with the Lyric was thrilling,” says Ashley Wheater, the artistic director of the Joffrey. “It was a beautiful collaboration, and we’re excited about the possibility of future collaborations – there are so many wonderful pieces out there, and also the potential to start from scratch and commission something new.”

Wheater is thinking about future collaborations not just because Orphée was successful, but also because the Joffrey will soon share the same space as the Lyric. In 2020, the Joffrey will move its performances from the Auditorium Theatre to the Civic Opera House, where the Lyric performs.

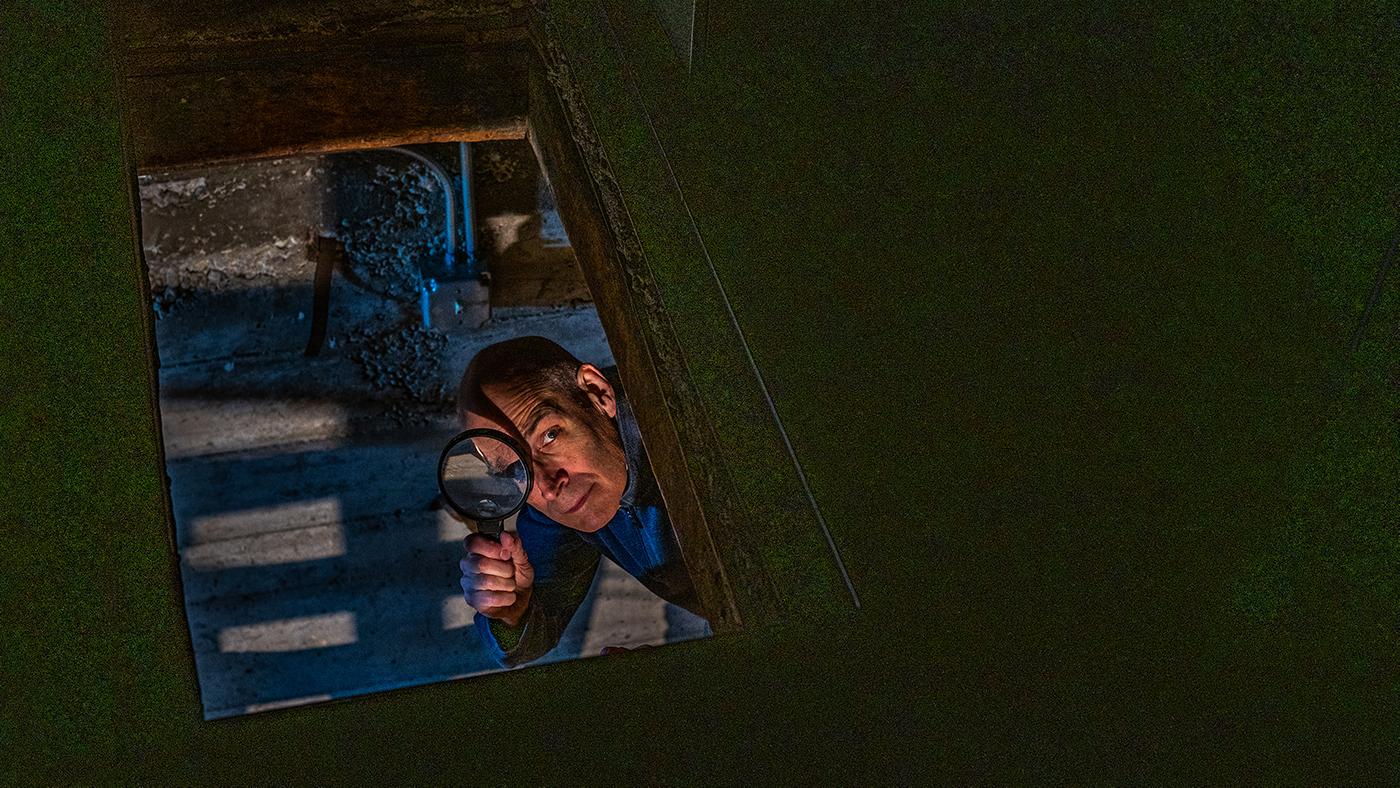

"The size of the Lyric stage opens up endless possibilities," says Ashley Wheater, the artistic director of the Joffrey. Photo: Todd Rosenberg Photography

"The size of the Lyric stage opens up endless possibilities," says Ashley Wheater, the artistic director of the Joffrey. Photo: Todd Rosenberg Photography

“The size of the Lyric stage opens up endless possibilities,” Wheater says. (The Civic is the second-largest opera house in America, after New York’s Met.) “It allows the dancers to go to the furthest edges of movement, which is such a liberating and freeing experience. There have also been works that I have wanted to do in the past that we were unable to stage because of technical capabilities; now we can try some of those.”

Already the Joffrey has been able to chart new territory for themselves, by joining with singers to realize an opera, Orphée, that contains evocative interludes meant to accompany ballet. One aspect of Gluck’s reforms was to tie the orchestral passages of opera into the drama, instead of using overtures just as curtain-raisers and interludes as opportunities to stop the action and interpolate dance. “I have felt that the overture ought to apprise the spectators of the nature of the action that is to be represented and to form, so to speak, its argument,” he wrote in a famous 1767 document that set out his principles.

There are thus ample opportunities for dance during Orphée, although opera companies rarely take advantage of them when staging the work nowadays. Another of Gluck’s reforms was a turn towards simplicity from the highly standardized, overly embellished, artificial works of previous decades. His stripped-down Orphée has only three roles and a simple structure: perfect for the inclusion of ballet to fill out some of the details and further express the emotional struggles of the characters.

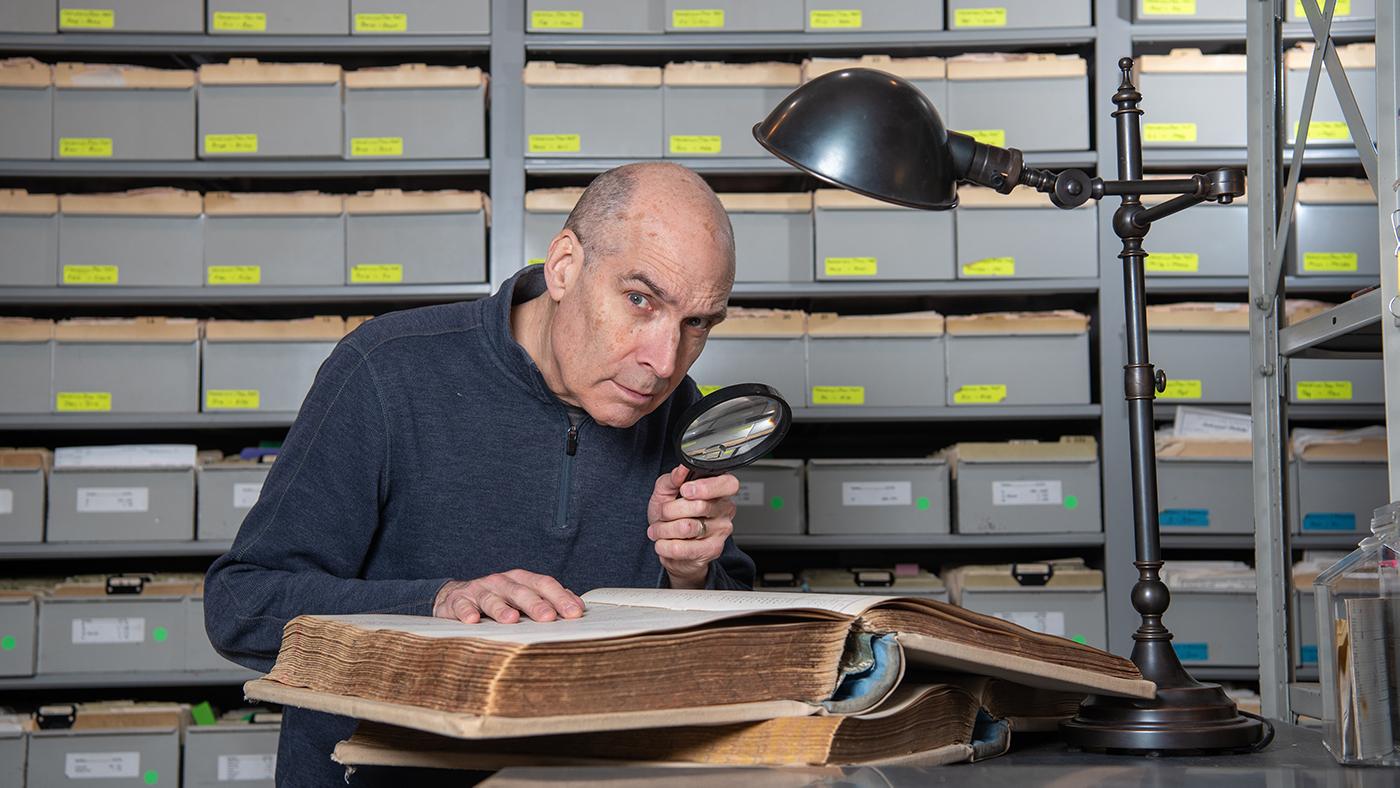

Orphée originally included passages meant for ballet, so it's a fitting work for the Lyric and the Joffrey. Photo: Todd Rosenberg Photography

Orphée originally included passages meant for ballet, so it's a fitting work for the Lyric and the Joffrey. Photo: Todd Rosenberg Photography

Gluck’s use of dance is unsurprising, for he also plays a seminal role in the history of ballet. Around the same time as the premiere of Orphée, ballet was beginning to emerge as its own independent art form out of its role as a secondary entertainment in works of opera or other grand theater. The “ballet d’action,” or plot ballet, in which dance alone was used to tell a story, was just starting to coalesce. And who wrote the first continuous score for a ballet d’action? None other than Gluck, whose Don Juan premiered in 1761.

Clearly, Orphée is a fitting work to inaugurate a collaboration between opera and ballet. But there’s one further reason that this collaboration was special and appropriate. John Neumeier, who choreographed and directed the production, is from Milwaukee and received much of his early dance training in Chicago. According to Wheater, Neumeier’s first performance as a young boy was at the Lyric. So Orphée acts as a sort of bookmark in multiple ways: as a homecoming for Neumeier, and as a new beginning rife with possibilities for the Lyric, the Joffrey, and Chicago’s arts scene as a whole.