The Black- and Woman-Led Success of a Chicago Ice Cream Company

Daniel Hautzinger

February 7, 2019

Boss: The Black Experience in Business is available to stream.

Only one Fortune 500 company has ever been headed by a black woman – Ursula Burns, who ran Xerox from 2009 to 2016 – and that number is indicative of the immense challenges black women and other women and people of color still face in climbing the corporate ladder. So imagine what it must have been like for Jolyn Robichaux, a 43-year-old widow with two young children and no business education, to take over Baldwin Ice Cream almost five decades ago, in 1971.

Her husband, Joseph, had been an executive at the Chicago-based Wanzer Milk Company and bought Baldwin in 1967. Upon his sudden death from leukemia in 1971, Jolyn decided to take over as president. “Why should I waste my time [looking for a replacement]?” she said. “I’ll just do it myself.” Over her more than twenty years heading the company, sales increased at least twelve-fold, according to her accounting.

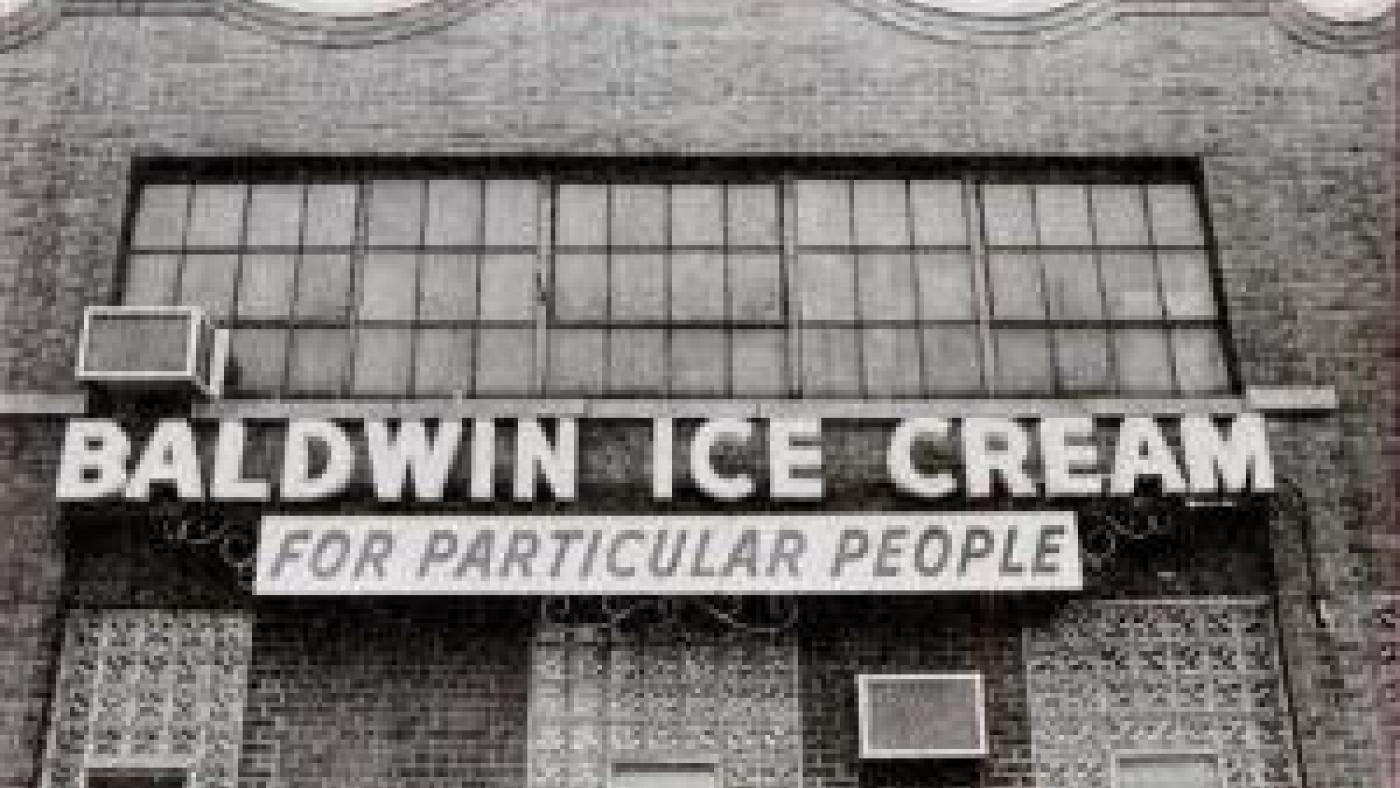

Baldwin Ice Cream had been around for half a century by the time Robichaux took over. In 1921, seven African American postal workers joined together to open an ice cream parlor at 53rd and State Streets in Washington Park, naming their shop Seven Links Ice Cream. By the 1940s they had seven locations throughout the South Side, and, despite the aptness of their name, had rebranded as the Service Links Ice Cream Company. In 1946, Kit Baldwin, one of the founders, bought out his partners and named the company after himself.

Baldwin expanded the business beyond standalone parlors, offering his ice cream through small South Side grocers beginning in 1955. When he died in 1961, the company quickly went through two presidents before the Robichauxes bought it at the behest of the previous leader, who wanted the company to remain in African American hands, especially since it served a predominantly black community. “My husband was chosen because he was the only black man that [the previous owner] knew that had any involvement in the dairy business,” Robichaux recalled to the Chicago Tribune. (Joseph Robichaux was also a Democratic committeeman in Chicago and a coach who trained track-and-field athletes, including for the Olympics.)

Jolyn Robichaux was not unfamiliar with being a trailblazer. The daughter of a dentist in Cairo, Illinois, she was the first African American employee of Betty Crocker. But being an executive was different. “In the early years, some people were uncomfortable with me,” she told the Tribune. “When I went in, the whole room would be filled with people looking at this oddity, this black woman who’s going to run the company,” she remembered in another interview.

But she also believes there was a benefit: “Being a black woman has actually helped me,” she said. “I was different, and nobody forgot who I was.” And she brought reinforcements, instituting women in many of the company’s management positions: her sister was the vice president, her mother was the financial manager, and a niece became a sales manager and account executive.

Robichaux’s success at the head of Baldwin was a result of her decision to focus on wholesale over standalone parlors. The last neighborhood shop, in Chatham, closed in 1992. But Robichaux had obtained concession rights at O’Hare Airport nine years earlier; Baldwin operated five stores there. And in 1989 she got Jewel, Dominick’s, Omni, and Cub Foods to sell Baldwin in their stores throughout the Midwest. She received a “National Minority Entrepreneur of the Year” citation from Vice President George H. W. Bush in 1985.

Despite her achievements, Robichaux did have one disappointment, according to her niece: the failure of a brandy-spiked black-eyed pea-flavored ice cream.

After two decades as president of Baldwin, Robichaux retired to Paris, selling the company to the scion of another prominent black business in Chicago: Eric Johnson, the son of Johnson Products founder George Johnson. Baldwin Ice Cream is now a part of Baldwin Richardson Foods Company. While it no longer has stores or sells ice cream, the company still manufactures syrups, fillings, sauces, and toppings for desserts and other foods.

When Robichaux died in 2017, not just Chicago newspapers but also The Wall Street Journal honored her with obituaries. Almost thirty years after her retirement, here's hoping more African American women are given the opportunity to replicate her sweet success.