How Pullman Porters Laid Groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement

Daniel Hautzinger

February 22, 2019

The Pullman Company was one of the more successful industrial companies in the United States, worth more than $200 million at a peak in the 1920s, but the African American men who worked as railroad porters on its luxurious “Palace cars” made less than a livable wage, if you didn’t count their tips; worked 400 hours or for 11,000 miles of travel a month and up to 20 hours a day; slept on the couches in the smoking car, and only when they weren’t in use; and had to buy their own uniforms, provide their own shoe polish, and pay for their own meals. Plus, they had to smilingly serve white passengers in a servile manner, making their beds, shining their shoes, helping them in any manner. Many of the early porters were ex-slaves.

And yet, for black men in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, being a Pullman porter was an enviable position, much better than most jobs available to them at the time. Porters were a well-respected part of the black middle class, counting among their ranks such people as the designer and artist Charles Clarence Dawson and Thurgood Marshall’s father. The Pullman Company was the largest employer of African American men in the country.

Not that George Pullman was kind to his employees. “[Labor leader Eugene] Debs once said that George Pullman was ‘as greedy as a horse leech,’ but that was unfair to leeches,” Jill Lepore memorably put it in The New Yorker. He had built a company town south of Chicago to keep workers close to the factory and prevent them from striking – with the added benefit that rents and other outlays now went to him. As one worker famously said, “We are born in a Pullman house, fed from the Pullman shops, taught in the Pullman school, catechized in the Pullman Church, and when we die we shall go to the Pullman Hell.”

When Pullman slashed wages by as much as half after an 1893 financial depression, but didn’t commensurately cut rents or food prices in his company-controlled town, his workers went on strike, in one of the largest labor protests in American history. They were violently put down by national troops.

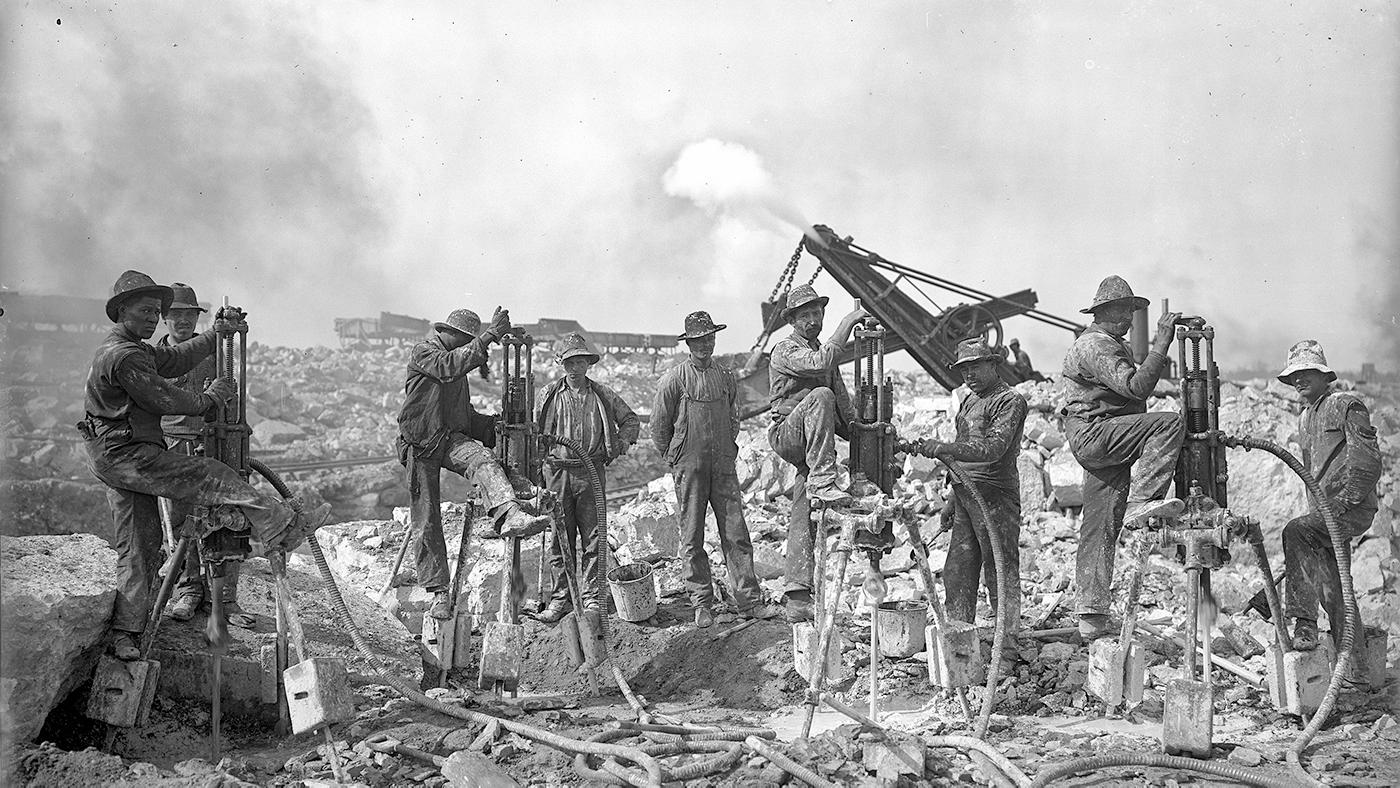

Members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in front of the 12th Street Station, gathered once they had finally been recognized by the Pullman Company

Members of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in front of the 12th Street Station, gathered once they had finally been recognized by the Pullman Company

In the following decades, the Debs-led American Railway Union made advances on behalf of the workers. Unfortunately, those benefits didn’t apply to the African American porters, who were outranked by every other employee. At its first meeting, in 1894, the American Railway Union had voted 112 to 110 not to allow African Americans to join, a decision that Lepore says “set back the cause of labor for decades.” Instead, black workers formed the Anti-Strikers Railroad Union and worked as scabs in the place of their striking white counterparts.

As the porters observed white Pullman employees gaining better contracts through the union, they decided to organize themselves. Their first attempt to unionize came in 1909, but the company derailed it by forming a false front company-led union and firing anyone trying to form a separate one. In 1925, the porters made a more concerted effort and approached the fiery A. Philip Randolph, who did not work for Pullman and therefore was safe from firing, to lead a new union. At a secret meeting on August 25 in Harlem, Randolph spoke to a crowd of some 500 porters. The next day, 200 joined the Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters.

By 1926, the Brotherhood had grown to more than 3,000 men. The local in Chicago, where the largest number of porters was based, was led by the gruff former porter Milton Webster. But the Pullman company refused to recognize the union, infiltrated its meetings with spies, and fired hundreds of employees associated with it. Female Pullman maids helped organize for the Brotherhood, as did the porters’ wives, raising money via bake sales and collecting dues to evade the company’s notice.

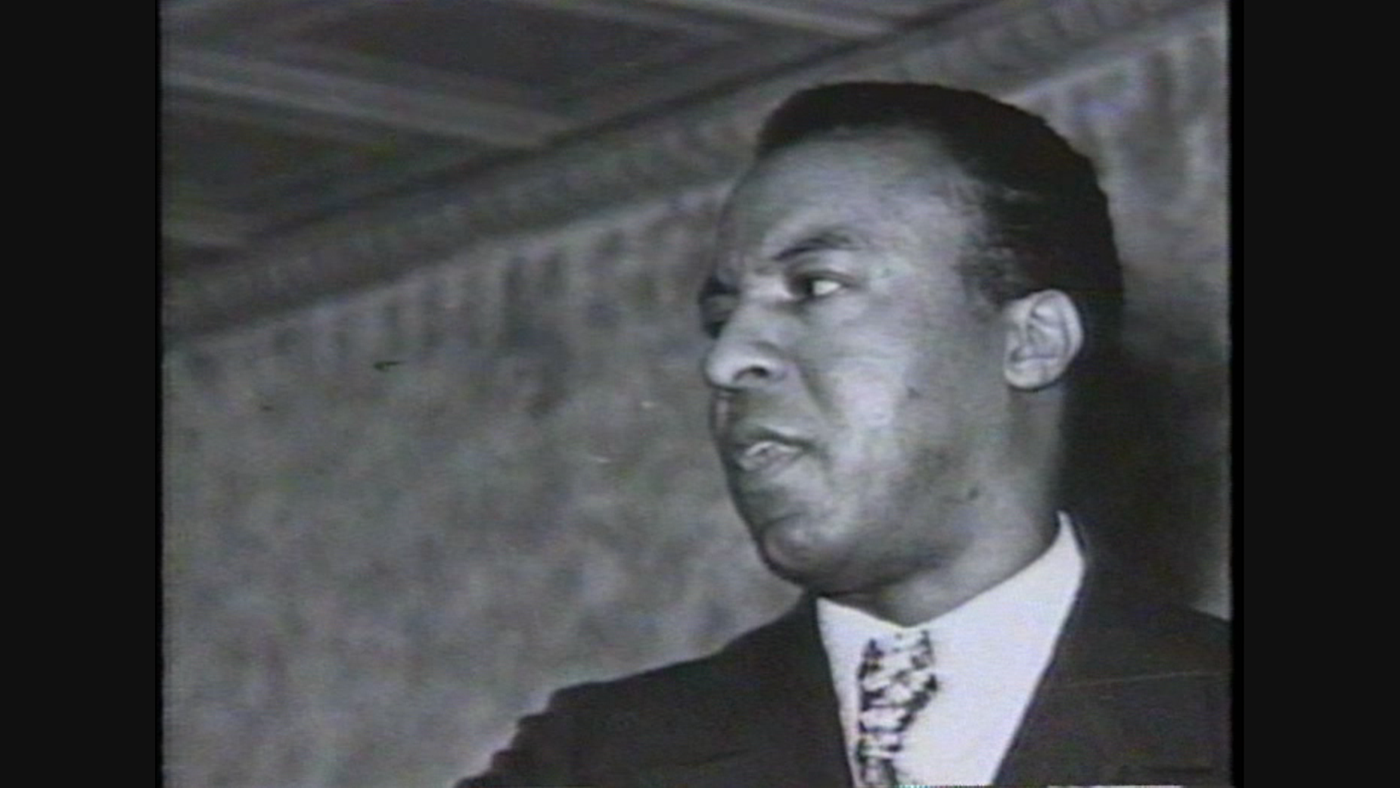

A. Philip Randolph led the Brotherhood, resisting attempts by the Pullman Company to buy him out

A. Philip Randolph led the Brotherhood, resisting attempts by the Pullman Company to buy him out

The Brotherhood suffered a serious setback in 1928, when Randolph backed away from a strike at the last minute and lost the support of half of the union’s members. The onset of the Great Depression the following year forestalled any further progress, as no one wished to jeopardize employment by striking in a time of such hardship.

President Roosevelt’s signing of pro-labor legislation as part of the New Deal in 1934 provided an opening for the Brotherhood, and in July of 1935, the Brotherhood finally forced the Pullman Company to the negotiating table. (Not without the Company trying dirty tricks: at one point, they sent Randolph a blank check, telling him to fill it in for any amount up $1 million in exchange for backing off. He refused.) Two years later, on August 25, 1937 – exactly twelve years after the founding of the Brotherhood – they reached an agreement that included pay raises, hour reductions, and job security. The Brotherhood was the first black union in the country to successfully negotiate with a company.

That success was a courageous example of triumph over injustice, demonstrating the organizational and negotiation skills necessary to force change. It was a Pullman porter named E.D. Nixon who paid Rosa Parks’s bail in Montgomery, Alabama and asked a young Martin Luther King, Jr. to lead a bus boycott there. Not only did the porters improve their own lives and working conditions through tenacious organizing; they also laid groundwork for the civil rights movement.