The 125th Anniversary of One of America's Biggest Strikes

Daniel Hautzinger

May 10, 2019

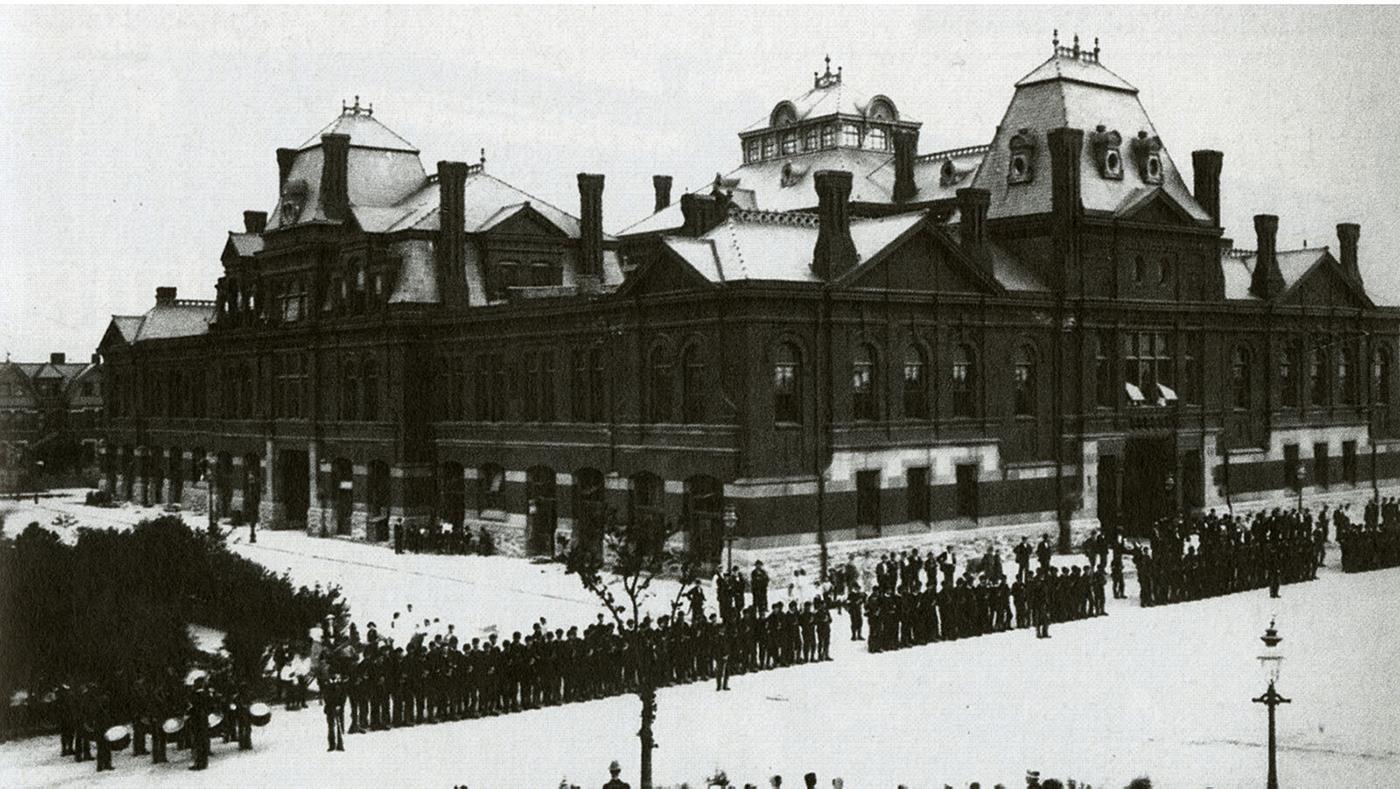

Pullman was supposed to be “The World’s Most Perfect Town.” The 4,000-acre community designed by the architect Solon Beman and landscape architect Nathan Barrett on behalf of George Pullman was fourteen miles south of the crowded, dirty neighborhoods of Chicago. It had its own school, church, parks, library, theater, and hotel, while each of its 531 varied brick homes had its own yard – a huge step up from the urban slums where most workers lived. The laborers who lived in those homes could walk to work at the Pullman Palace Car Company plant in the town, where they constructed luxury sleeper cars for railroads.

George Pullman, who had become extremely wealthy from his business, wanted his town to be free of the kinds of workers who would participate in costly strikes – hence the attractive amenities. But the requirement for entrance into his idyllic company town was a 32-page lease that had restrictions meant to ensure social and moral health. You had to ask permission if you wanted plants. You couldn’t sit on your front porch and had to follow a dress code when you left the house. The only people who could purchase alcohol in town were hotel guests.

Pullman owned the whole town, which generated a profit for his company. The company served not only as employer to the workers who lived there, but also as landlord, shopkeeper, and town council. “We are born in a Pullman house, fed from the Pullman shops, taught in the Pullman school, catechized in the Pullman Church, and when we die we shall go to the Pullman Hell,” one laborer said. While many observers marveled at the order and cleanliness of the town, seeing in it a new future, some viewed it as more malevolent: an 1885 Harper’s Monthly report accused it of being paternalistic and restricting rights.

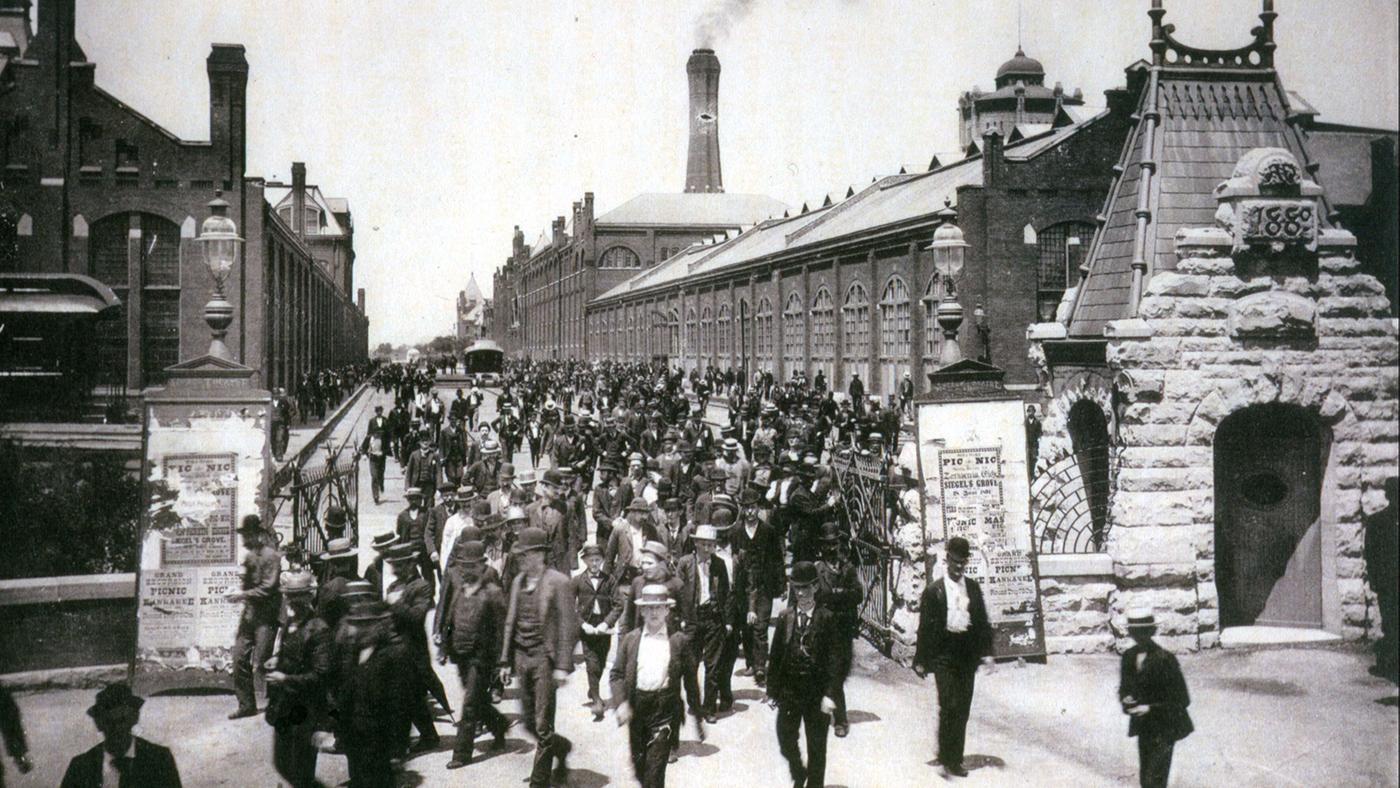

Pullman was supposed to be idyllic, with its rows of brick houses for workers. Photo: Courtesy Chicago History Museum

Pullman was supposed to be idyllic, with its rows of brick houses for workers. Photo: Courtesy Chicago History Museum

Pullman workers began to chafe against the restrictions, but it wasn’t until 1894 that resentment flared into major action. A national economic downturn had begun in 1893, and the Pullman Company was suffering, along with many other businesses. George Pullman slashed the wages of his workers by a quarter or more – but didn’t commensurately reduce their rents or the price of food.

On the morning of May 11, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Pullman workers had asked for a raise, and that George Pullman had responded by sharing “some facts which they should take to heart,” namely, that the continuation of work necessitated sacrifices from both the workers and the company. The Tribune editorialized: “Had [the Pullman company] not tried to save its employés [sic] to some extent from the consequences of Democratic malignity and imbecility,” – the paper blamed the Democratic party and President Grover Cleveland for the economy – “and had it consulted its own interests only, the works would have been closed till better times came.” Assuming many of the workers had voted Democratic, the paper concluded, “Instead of scolding Mr. Pullman they should scold themselves.”

That day, 125 years ago, the workers decided to go on strike.

George Pullman, pictured with his wife, Harriet, wanted to avoid strikes by building a company town. Photo: Courtesy Chicago History Museum

George Pullman, pictured with his wife, Harriet, wanted to avoid strikes by building a company town. Photo: Courtesy Chicago History Museum

A month later, on June 12, the first annual meeting of the newly formed American Railway Union (ARU) took place in Chicago. In his opening remarks, the union’s leader Eugene Debs – later a five-time candidate for President of the United States as a socialist – colorfully likened George Pullman to the devil. “So happily are the principles of Pullman blended with the policy of the proprietor of the lake of fire and brimstone that the biography of one would do for the history of the other,” he said. Debs himself was described as a “dictator” by the likes of the pro-business Tribune.

Debs did not initially want the ARU to become involved with the Pullman strike. But after a nineteen-year-old Pullman sewing worker named Jennie Curtis spoke at the meeting and explained that the entire salary she was paid by the Pullman Company went back to them in the cost of room and board, the ARU voted for a boycott of Pullman cars. (They also voted by a slim margin during that first meeting not to allow African American men in the union, a decision that later led to the formation of a separate black union, the famous Brotherhood of the Sleeping Car Porters.)

The boycott began on June 26. ARU workers refused to handle, inspect, switch, or haul Pullman cars or equipment, and sometimes even unhitched them from trains. The strike eventually stopped trains in 27 states, grinding most rail transport in the West and Midwest to a halt for a month. The historian Jill Lepore has called it “one of the single biggest labor actions in American history.” And it began in a town meant to prevent strikes.

The Pullman strike failed, but the workers did attract broad sympathy. Photo: Courtesy Chicago History Museum

The Pullman strike failed, but the workers did attract broad sympathy. Photo: Courtesy Chicago History Museum

Despite its size, the strike failed. Violence erupted from both strikers and police, some of whom were given orders to shoot and kill any demonstrator found destroying property. President Grover Cleveland deployed federal troops to Chicago and other areas (the mail wasn’t moving, so the strike had become a national issue). By the end of July, without broader support from other unions, the strike had fizzled and been defeated.

Debs and seven other organizers were charged with violating a federal injunction against aiding the strikers. Clarence Darrow, at the time a relatively unknown lawyer for a Chicago railway, quit his job to defend Debs, beginning his career as a legendary trial lawyer and crusader. He lost the case, and the organizers were sentenced to a short term in a county jail in Woodstock, Illinois; their conviction was upheld by the US Supreme Court.

Despite the indictment and general public animosity towards the boycott, the Pullman workers did receive wide sympathy while George Pullman was broadly censured for his treatment of them. Even the paternalistic Tribune changed its tone and castigated Pullman. When he died in 1897, he was so disliked by his workers that he was buried in a lead-lined coffin inside a reinforced steel and concrete vault in Graceland Cemetery; several tons of cement were poured over the vault, lest any disgruntled employees try to dig up and desecrate his body. The following year, the Illinois Supreme Court ordered the Pullman Company to give up ownership of residential property in Pullman. “The World’s Most Perfect Town” was now just a town.