The Horrific Violence and Continuing Legacy of Chicago's 1919 Race Riot

Daniel Hautzinger

July 26, 2019

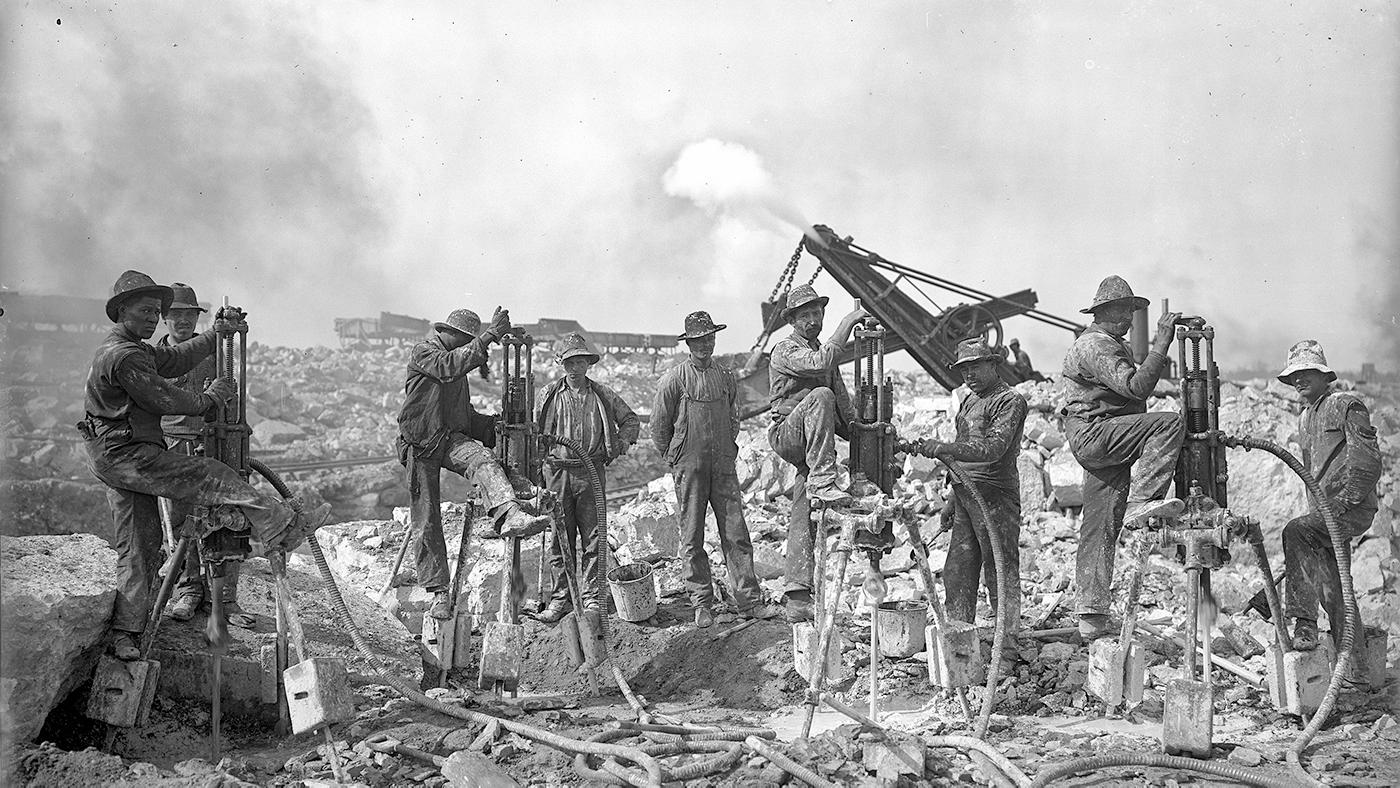

The North was supposed to be better. Beginning in the mid-1910s, thousands of African Americans left the South for better economic opportunities and to escape racial violence, in a movement that became known as the Great Migration. World War I only spurred further migration, as the departure of men to become soldiers left labor shortages and the wartime economy ramped up. From 1910 to 1920, Chicago’s black population more than doubled, from around 44,000 people to almost 110,000.

But with that explosive growth came increasing racial tension, as black Southerners began competing with white Northerners for jobs. From 1917 through 1919, some two dozen black homes in Chicago were bombed. A six-year-old girl named Garnetta Ellis died in one attack; none of the bombings were ever solved by the police. As soldiers returned from the war to find African Americans in many of the jobs they used to hold, the tension escalated. The early summer of 1919 saw reports of white mobs attacking black people.

Then, on July 27, 1919—one hundred years ago—a seventeen-year-old boy named Eugene Williams accidentally drifted across an invisible but acknowledged line separating the white and black parts of the 29th Street Beach. A white man standing on the beach named George Stauber pelted Williams with rocks. One hit Williams in the head, and he drowned.

Williams’s friends tried to get a black cop to arrest Stauber, but a white policeman intervened, eventually arresting someone from the gathering crowd of black people calling for Stauber’s arrest. A fight broke out, and the simmering tension finally ignited into a horrific, six-day-long race riot, the worst in Chicago’s history. “I thought of the hate on the faces of these hoodlums who were running to attack us, and I thought that they looked exactly like a pack of wild animals out for a kill,” a young black man later wrote of his experience during the riot. By the time rain and the deployment of the Illinois National Guard calmed the violence, 38 people were dead, more than 500 were injured, and thousands were left homeless.

A mob runs with bricks during the 1919 race riot in Chicago. Photo: Chicago History Museum / The Jun Fujita negatives collection

A mob runs with bricks during the 1919 race riot in Chicago. Photo: Chicago History Museum / The Jun Fujita negatives collection

Chicago wasn’t the only city to experience such trauma: the summer of 1919 is known as “Red Summer” for the race riots that swept the country from Syracuse, New York to Bisbee, Arizona. Hundreds of African Americans were killed by white mobs—researchers believe there were around 250 black deaths over ten months, in at least 25 riots—and thousands of homes and businesses burned in what the historian John Hope Franklin has called “the greatest period of interracial strife the nation has ever witnessed.”

But Chicago, a Northern city that was supposedly less racist than the South, experienced some of the worst of the violence. “The riot is a demonstrative event in showing Chicago to not be some sort of haven,” says Simon Balto, an assistant professor of history and African American studies at the University of Iowa whose 2019 book Occupied Territory: Policing Black Chicago from Red Summer to Black Power uses the 1919 riot as a starting point to examine “racially repressive” policing in Chicago neighborhoods, which Balto argues are “overpatrolled and underprotected,” in the words of a black Chicago Police officer.

“1919 represents a moment in time that is not that distant in the past in which you can see the violence of white supremacy enacted all across the country,” Balto says. “It is kind of a high-water mark of violence, but it neither comes from nowhere, nor does it solve anything. When things return to quote unquote ‘normal,’ that normal is still defined by incredible racial conflict and white-on-black violence.” Take the bombing of Tulsa’s “Black Wall Street” in 1921, to name one later instance. “The riot exists within this larger and years-long moment of essentially white terrorism to protect neighborhood boundaries,” Balto continues.

According to Balto, the racial tension that led to the riots emerged not only from the economic competition of whites and blacks in the time around the war (the Red Summer riot in Elaine, Arkansas began after black sharecroppers who had joined a union were attacked), but also from the influx of black people into spaces near or in white neighborhoods. This attempt to keep black people out of white areas grew into a formidable system of legal segregation in the years and decades following the riot.

A crowd of men and armed National Guard stand in front of the Ogden Cafe during the 1919 race riot in Chicago. Photo: Chicago History Museum / The Jun Fujita negatives collection

A crowd of men and armed National Guard stand in front of the Ogden Cafe during the 1919 race riot in Chicago. Photo: Chicago History Museum / The Jun Fujita negatives collection

“The riot does not all the sudden make black people acquiesce to white demands for them to stop trying to move into white neighborhoods,” Balto explains. “It proves that these extra-legal means of trying to enforce segregation in Chicago are not going to work. So you get the creation of legal means of segregation, in redlining and restrictive covenants.” Redlining was the government-mandated practice of restricting loans and other financial services for black neighborhoods; restrictive covenants were agreements signed by homeowners that they would not sell to black people. “When we look at Chicago as being one of, if not the most, segregated city in America,” Balto says, “that all springs out of the aftermath of 1919.”

Balto also argues that the Chicago riot “was really suggestive of the direction that policing was ultimately going to take in terms of how it really prioritized the interests of white folks at the expense of black folks.” An all-white jury convened to investigate the riot said that, “It is the opinion of this jury that the colored people suffered more at the hands of the white hoodlums than the white people suffered at the hands of the black hoodlums,” and, in fact, the majority of the violence was committed by whites against blacks: there were twenty-three black deaths and fifteen white, and five of the whites seem to have been killed as they were committing violence. “Generally speaking, the Negroes were orderly after the initial riots, in which they acted largely in self-defense, aggravated by very real fear of a general massacre,” an Illinois Reserve Militia captain wrote.

But the majority of people arrested were black. As the State’s Attorney put it, “There is no doubt that a great many police officers were grossly unfair in making arrests. They shut their eyes to offenses committed by white men while they were very vigorous in getting all the colored men they could.” The grand jury agreed: “The cases presented to this jury against the blacks far outnumber those against the whites,” they said, and refused to continue their trial until they saw more white people charged. Only three men were convicted of riot-related killings, and they were all black teens. Two had their sentence commuted later due to suspicion that their confessions had been coerced.

A house destroyed in the riot. Photo: Chicago History Museum / The Jun Fujita negatives collection

A house destroyed in the riot. Photo: Chicago History Museum / The Jun Fujita negatives collection

There were also reported instances of white policemen siding with white rioters either by standing by during violence against black people or joining in the violence themselves. This, combined with the disproportionate arrests of black people, “laid bare core problems of policing for black people: that they may not be properly protected in moments of need; and that police may abuse, harass, and violate them for no reason other than the color of their skin,” Balto writes in his book.

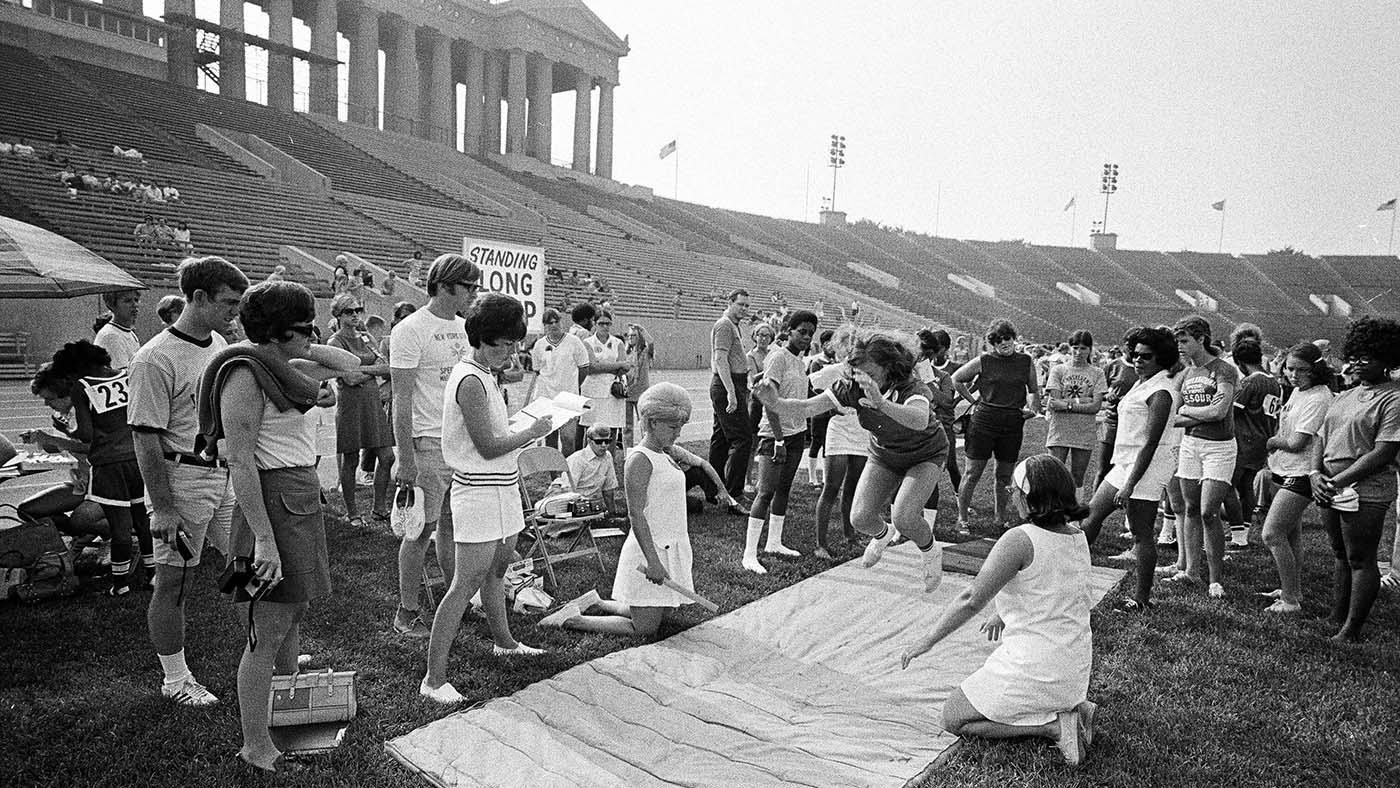

In the aftermath of the riot, a commission consisting of six black and six white men was created to study the causes. They released their detailed report in 1922, detailing discrimination in numerous segments of everyday life, urging reforms and condemning segregation. But most of the reforms were never enacted. “In terms of the reforms, it has just been the same story over and over again for a hundred years,” Balto says. “You get people suggesting reforms, and those reforms never get put in place.”

Beyond the failure to enact reforms, the Red Summer and the Chicago race riot of 1919 have also been largely forgotten, although groups are aiming to change that. “Americans in general—white Americans especially, I would say—do not do a good job wrestling with the ugly parts of our history,” Balto says. “And 1919 is a really ugly part of this country’s history. It’s hard and difficult to grapple with. What does it mean and say about Chicago’s history to have this as part of the city’s fabric? Once you ask that question, then you actually have to start trying to answer it.”