How Chicago's Ballparks Reflect the American City (For Better or Worse)

Daniel Hautzinger

July 31, 2019

“Baseball is more closely connected to place than any other major American sport,” the Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic Paul Goldberger writes in his new book Ballpark: Baseball in the American City, “and for most of the game’s history… it has been a game of the city.” For Goldberger, the best baseball parks are intimately tied to their urban surroundings; that’s a prime reason he celebrates Wrigley Field, which is on the cover of his book, but laments Guaranteed Rate Field in his survey of the history of baseball park design and how it reflects American attitudes towards cities. Whereas the Cubs’ home, especially before the recent new development around it, has always felt like a part of its neighborhood, the White Sox play today in a stadium surrounded by parking lots that could seemingly have been dropped into any city.

“What Wrigley speaks to most clearly is the indigenous connection between a great ballpark and the city around it,” Goldberger said in a recent phone conversation. “There’s a natural, almost organic connection between the neighborhood and the ballpark, and I think Wrigley really is the very best we have anywhere of that.”

Wrigley Field is one of only two remaining ballparks from the “Golden Age” of baseball fields, a period in the early twentieth century that saw the construction of some of baseball’s most beloved parks, including Shibe Park in Philadelphia, Fenway Park in Boston (the other surviving park), and Ebbets Field in Brooklyn.

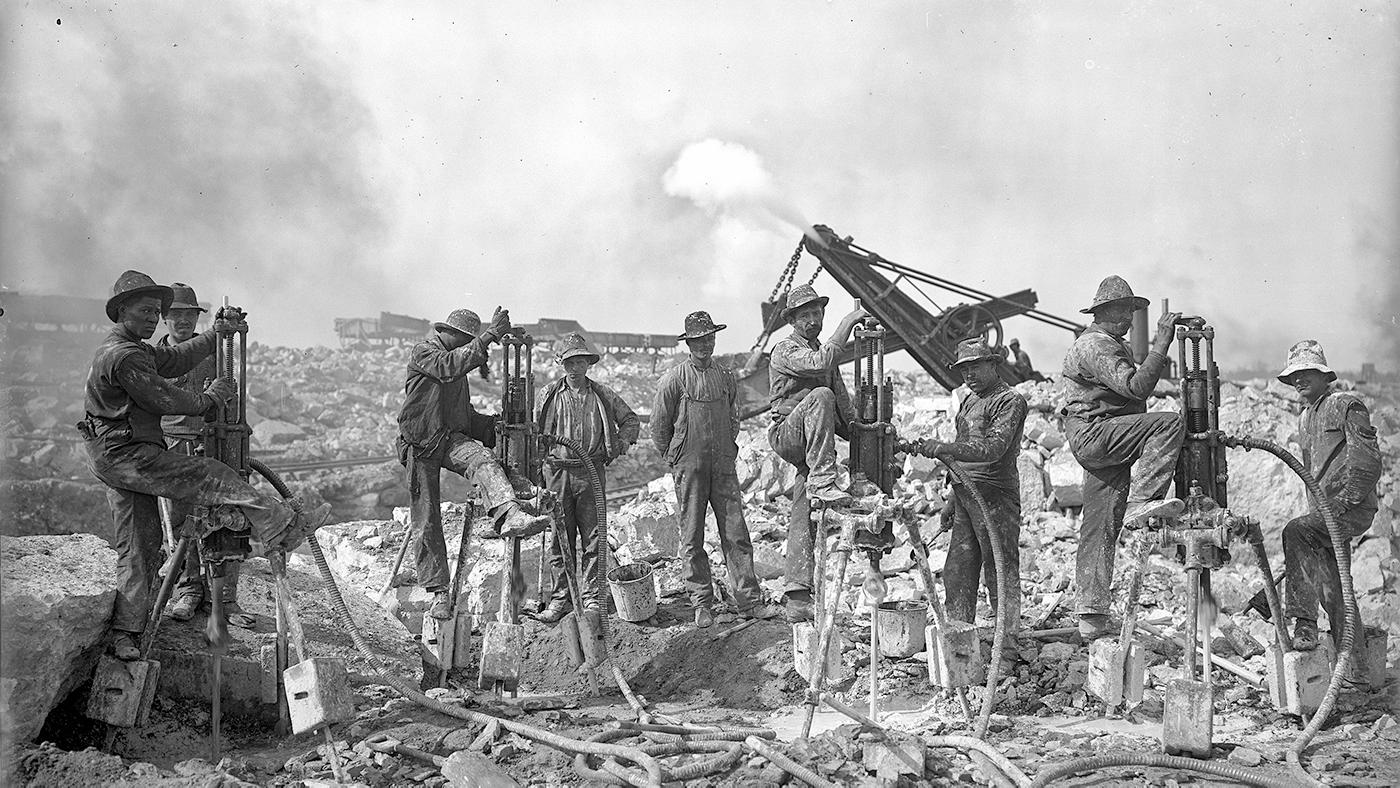

A postcard image of Weeghman Park, which became Wrigley Field, in 1914, the year it was built. Image: Wikimedia Commons

A postcard image of Weeghman Park, which became Wrigley Field, in 1914, the year it was built. Image: Wikimedia Commons

Wrigley was built in 1914 by a restaurateur named Charles Weeghman to house his team the Chicago Whales, which was part of the upstart but short-lived Federal League. Weeghman hired the architect Zachary Taylor Davis, who had designed White Sox Park (known as Comiskey Park) four years earlier, to design his North Side field, which he named after himself.

Despite their cherished status today, “Both Wrigley and Fenway were smaller and more ordinary at opening, and they grew and became somewhat more interesting and complex structures over the years,” Goldberger said. “But neither was created as this beautiful, complete object.”

Wrigley, for one, took decades to accrue its most recognizable features. When Weeghman became the owner of the Cubs after the collapse of the Federal League in 1916, he moved the team to his new park. It was eventually renamed Cubs Park and then Wrigley Field, after the chewing gum magnate William Wrigley, who took over ownership of the team from Weeghman. Along with the team president Bill Veeck, Sr., Wrigley began to expand seating and build a devoted audience. Wrigley’s son, Philip Knight Wrigley, added the distinctive red sign outside the park in 1934, while Veeck's son Bill put up the ivy on the outfield walls in 1937, inspired by Perry Stadium, a minor league park in Indianapolis.

Beautifying the park was a conscious strategy to appease the fans of a losing team. As Goldberger reports, Veeck wrote that P. K. Wrigley’s solution to selling tickets “was to sell ‘Beautiful Wrigley Field’; that is, to make the park itself so great an attraction that it would be thought of as a place to take the whole family for a delightful day.”

Wrigley Field's intimacy and its connection to the city around it are part of what Goldberger admires most about the park. Photo: Russell Hughes

Wrigley Field's intimacy and its connection to the city around it are part of what Goldberger admires most about the park. Photo: Russell Hughes

Goldberger emphasizes that the architectural qualities of a ballpark are only a small part of what makes one great, however. “The things that make a ballpark beloved and iconic, to use that overused word—quality of architectural design is certainly a part of it, but it’s far from the whole thing,” he said. “It’s also the team itself, and the people involved in it, and the nature of the community. It’s intimacy more than anything else, in the sense that everyone’s in it together in a very benign way.”

“The reality is,” he continued, “while there are many wonderful physical things about Wrigley—and I’m always sort of struck by the power of the steel structure, and also by the quirkiness of some of the seating areas—nobody would say that it is as beautiful as a cathedral or something like that. It’s that combination of funkiness and monumentality that is so cool. Those are qualities that almost never exist in the same building, but they do there.”

Guaranteed Rate Field (originally New Comiskey Park), on the other hand, which opened just south of the park it replaced in 1991, offers only monumentality and none of Wrigley’s famed intimacy. (Its construction also required the removal of roughly seventy-eight houses, “most of which were occupied by African American families,” Goldberger writes.) One writer has determined that the front row seats of Guaranteed Rate’s upper deck are farther from the field than the back row seats in old Comiskey.

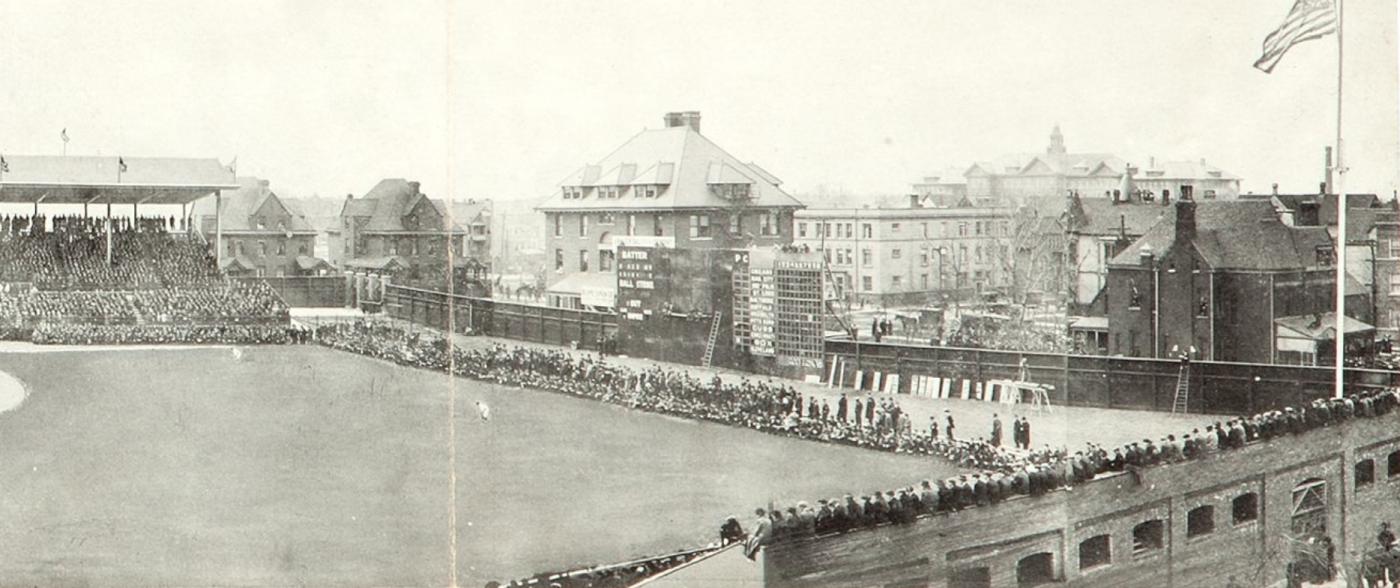

Old Comiskey Park was built by the same architect as Wrigley Field, four years earlier. Photo: Rick Dikeman via Wikimedia Commons

Old Comiskey Park was built by the same architect as Wrigley Field, four years earlier. Photo: Rick Dikeman via Wikimedia Commons

Guaranteed Rate Field “is the last of the twentieth century’s concrete behemoths,” Goldberger writes. It is more similar to the much criticized, generally suburban “concrete doughnuts” of the 1960s and ‘70s—stadiums like Houston’s Astrodome that tried to house both baseball and football, at the cost of distancing fans from the field and cutting off any glimpse of their surroundings—than the more intimate, characterful, and integrated urban parks that immediately followed, like Camden Yards in Baltimore, which opened in 1992.

“I find New Comiskey to be a basically sad story,” Goldberger said. “It shouldn’t have happened, because by the time it happened we knew better.” Baseball teams like the Baltimore Orioles had come to understand that fans and players preferred smaller stadiums that were integrated into their urban surroundings and had idiosyncratic features that distinguished them from other parks. A plan for a field along those lines was floated when the Sox were replacing old Comiskey Park, but it didn’t gain any traction. New Comiskey Park’s architecture was essentially outdated within a year of opening.

The trend that Camden Yards inaugurated—and New Comiskey ignored—mirrored a broader trend in American urbanism: that of returning to cities and celebrating localism after postwar suburbanization. Baseball is “a metaphor for how we have chosen to deal with our cities, the extent to which we have seen them as a natural habitat versus the extent to which we have seen them as something to escape from, or, more recently, as something to try to return to,” Goldberger writes.

New Comiskey Park (now Guaranteed Rate Field) “is the last of the twentieth century’s concrete behemoths,” Goldberger writes. Photo: Ken Lund

New Comiskey Park (now Guaranteed Rate Field) “is the last of the twentieth century’s concrete behemoths,” Goldberger writes. Photo: Ken Lund

There is a new, troubling development in both ballparks and cities that has emerged in the wake of Camden Yards and the parks it inspired: the “developer-built city,” in Goldberger’s words. Epitomized by Atlanta’s SunTrust Park and its surrounding “Battery”—a privately owned, faux-urban setting of shops, restaurants, condos, and offices—it is also visible in the recent redevelopment of the area around Wrigley Field, although Goldberger is careful to distinguish between the truly urban Wrigley and the entirely private, newly created area of the Battery in Atlanta.

“The Battery is a whole other thing entirely: picking up and leaving the city, and creating this make-believe, pseudo-urban theme park way out in the suburbs,” he said.

“American history has often had significant public spaces that are technically private, and the ballpark is perhaps the most significant genre of them,” Goldberger said. “They are among our most important civic spaces. In this latest phase of ballparks, much of the city outside the ballpark gates is being privatized. The larger trends toward the privatization of public space are serious ones that we talk about in a lot of contexts, and I just wanted to add the ballpark to the larger context. The increasing compromise to the public realm is what makes something like Atlanta’s Battery so disturbing, because it’s all a private real estate development masquerading as a city. There’s something a little bit disingenuous about it, and it also generally doesn’t represent the diversity of the community, which is a sadness.”

Meet the husband-and-wife team that designed everything from uniforms to scorecards for P. K. Wrigley's Cubs, and learn about a little-discussed but integral aspect of the ballpark experience in these videos from our sister station WFMT introducing the White Sox organist and the Cubs organist.