The 1969 Clash Between the Counterculture and the Establishment in a Chicago Courtroom

Daniel Hautzinger

September 19, 2019

It wasn’t your typical court case. The defense appeared in judge’s robes and called a witness who later claimed to have dropped acid before taking the stand, while other witnesses read poetry and tried to sing songs. The judge ordered one defendant bound and gagged, and was later found to have violated standards of fairness in his attitude toward the defense.

The Chicago Eight conspiracy trial held in Chicago 50 years ago was an attempt to restore propriety and order after the chaos of the Democratic National Convention the previous year, but instead it did the opposite, inviting disorder into a federal courtroom and tarnishing the respectability of the very establishment forces it was meant to uphold.

The late 1960s were riven by conflict between the so-called establishment and the youthful counterculture. Disillusioned by the Vietnam War, young activists staged large-scale protests against the government, including at the ’68 Democratic Convention, when they were met with force in what a national commission later called a “police riot.” Despite the violence, polls found that most Americans approved of how Mayor Richard J. Daley and the city had handled the protests (the turmoil may have helped the law-and-order Richard Nixon easily defeat Hubert Humphrey in the presidential election that fall), and the city quickly moved to ensure that public opinion remained on its side.

On September 15, 1968, only a few weeks after the convention, WGN aired a documentary produced by the city that sought to portray the protesters as anarchic in order to justify the city’s response. In it, Daley claimed to have had intelligence reports that “certain people planned to assassinate the three contenders for the Presidency,” as well as himself. A Chicago police intelligence officer claimed to have information on plans to spike the water system with LSD and sprinkle the food of convention delegates with broken glass. A police officer from Los Angeles argued that the Chicago police had been restrained in their response “really beyond reason.”

The documentary, which aired in 140 American cities as well as in Canada and Britain, also showed protesters engaging in “anti-police ‘maneuvers,’ “ in the words of a Chicago Tribune review, including throwing stones at police officers. But the Tribune author also noted that it “contained disappointingly little footage of actual attacs [sic] upon the police.”

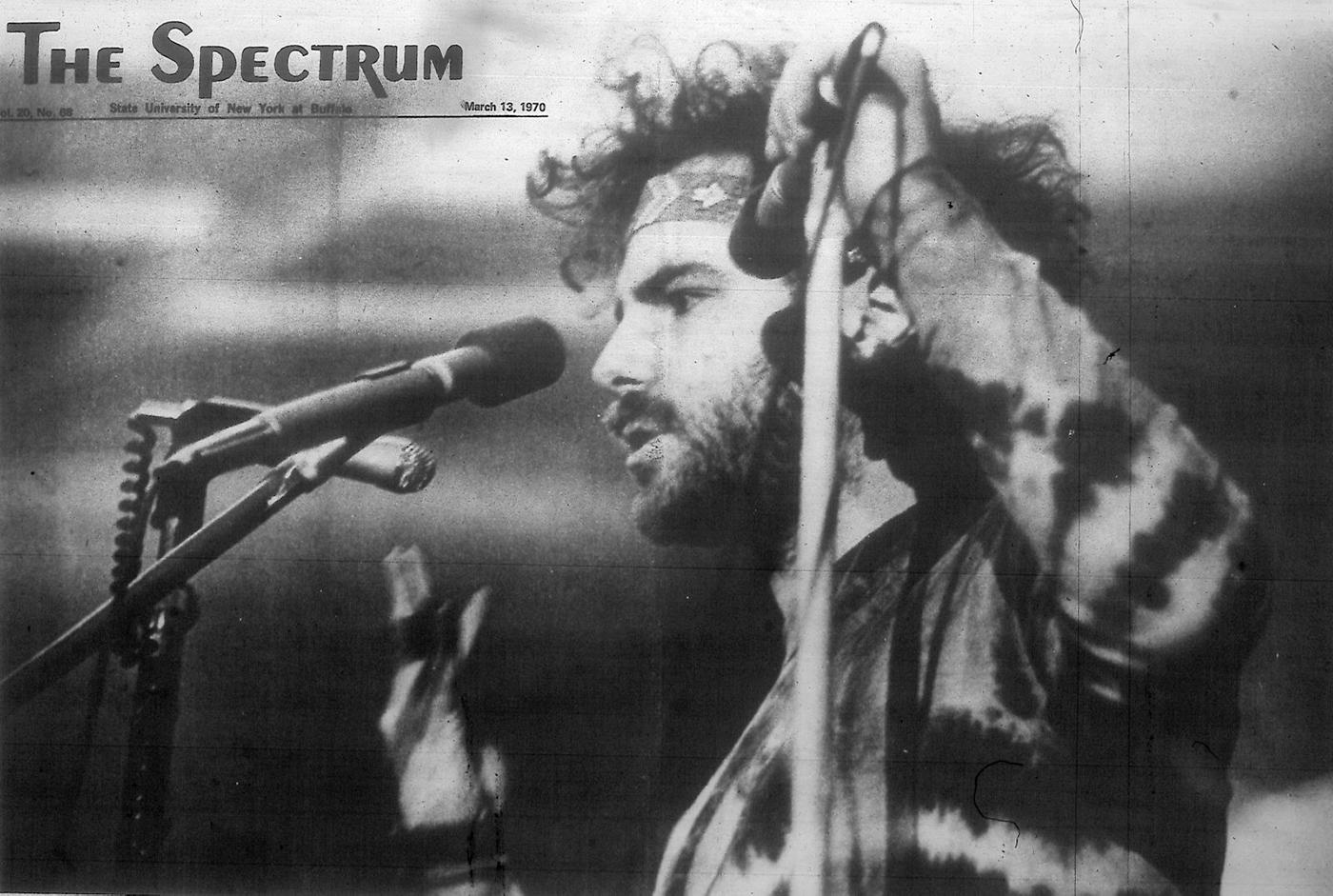

Jerry Rubin speaking at the University at Buffalo's Fillmore Room, one month after his conviction in the Chicago Eight conspiracy trial. Image: The Spectrum/Wikimedia Commons

Jerry Rubin speaking at the University at Buffalo's Fillmore Room, one month after his conviction in the Chicago Eight conspiracy trial. Image: The Spectrum/Wikimedia Commons

A few months after the documentary aired, a federal grand jury investigation into the tumult of the convention brought indictments against seventeen people: eight police officers, eight demonstrators, and one broadcasting company employee. The policemen were charged with false testimony or use of excessive force on demonstrators or reporters; four were recommended for firing. An NBC producer was charged for secretly recording closed sessions of the convention. And the eight demonstrators were charged for conspiring and crossing state lines to incite a riot under a controversial anti-riot section of the 1968 Civil Rights Act.

The Chicago Eight, as they became known, were David Dellinger, chairman of the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam (MOBE), one of the main activist groups behind the demonstrations; Rennie Davis, the Chicago coordinator for MOBE; Tom Hayden, a co-founder of Students for a Democratic Society; Abbie Hoffman, a cofounder of the Youth International Party (“Yippies”); Jerry Rubin, another Yippie leader; Lee Weiner, a research assistant, and John Froines, a chemistry professor, both of whom had participated in the demonstrations; and Bobby Seale, a cofounder of the Black Panther Party.

The trial of the Chicago Eight began on September 24, 1969, on the 23rd floor of the Dirksen Federal Building downtown. It was presided over by 74-year-old judge Julius J. Hoffman with the prosecution led by United States Attorney Thomas A. Foran and the defense by William Kunstler. Predicting that they would lose in the actual courtroom, the defense focused on the court of public opinion, hiring a public relations agent and holding media briefings as often as twice a day. The prosecution and the judge, meanwhile, were prohibited from discussing the case publicly.

“We were going for the nation,” Yippie cofounder Nancy Kurshan told WTTW in a documentary about the trial. (Kurshan was Jerry Rubin’s girlfriend at the time). “We wanted to talk to the nation about what we were trying to do, we wanted to win them with everything that we could think of.”

From the beginning, the defendants targeted Judge Hoffman, who became increasingly frustrated by their antics and by the spectators, who often laughed along. “For those who think that remarks of this court are funny, I would like to remind them that this is not the plaza downstairs [where demonstrators gathered],” the judge said on the very first day of the trial. Rubin and Abbie Hoffman appeared in judge’s robes at one point in an attempt to delegitimize the court. Shouting matches repeatedly broke out, with Foran often objecting to the defense’s tactics. Brawls occurred both in the plaza outside and in the building; the National Guard was called in for crowd control.

One of the most dramatic – and indelible – moments of the trial came in late October, when Judge Hoffman ordered Bobby Seale, the Black Panther leader, bound to his chair and gagged by a cloth and tape. Seale had requested a delay, as his attorney was ill when the trial started, but the judge had denied it, so Seale decided to defend himself. His frequent interjections incensed Hoffman, who ordered the court marshals to restrain him. The struggling Seale fell backward in his chair at one point as he attempted to yell through his gag about his right to speech. Hoffmann eventually mis-tried Seale, and the Chicago Eight became the Chicago Seven.

A courtroom illustration of Bobby Seale bound and gagged during the Chicago Eight conspiracy trial. Illustration: Franklin McMahon/Wikimedia Commons

A courtroom illustration of Bobby Seale bound and gagged during the Chicago Eight conspiracy trial. Illustration: Franklin McMahon/Wikimedia Commons

“Here you had a black man in an American courtroom tied to a chair with tape around his face and around his mouth,” the Chicago Sun-Times reporter Bob Greene told WTTW for the documentary. “It’s as damaging a thing as I’ve ever heard of a judge doing.”

The trial proceeded for five months in a similar theatrical, unbecoming manner. The defense’s witnesses included stars of the counterculture such as Timothy Leary, Pete Seeger, Norman Mailer, and Paul Krassner, who later claimed to have dropped acid for the occasion. Judy Collins and Arlo Guthrie tried to sing but were cut off by Judge Hoffman. Allen Ginsberg was asked to read some of his poems by Foran and began a Hindu chant in an attempt to calm an argument that broke out.

On February 18, 1970, the jury found five of the seven guilty – not of conspiracy, but of individual acts of incitement. (As the Tribune explained it: “In effect, what the jury decided was that the five men were guilty of provoking the convention disorders, but that they did not act in a widespread and planned conspiracy to do so.”) Judge Hoffman had already cited the defense lawyers and the defendants, including Froines and Weiner, who had not been found guilty, with contempt, so they still received a prison sentence. (Kunstler’s contempt citation was the longest, at four years and 13 days.)

The contempt citations, convictions, and prison terms were all wiped away on appeal. On November 21, 1972, the convictions were reversed. The Court of Appeals found that, while “there appears to be sufficient evidence for a new trial and appears to be sufficient evidence that the crime was committed,” Judge Hoffman and Foran had committed trial errors. (One justice did say the anti-riot law was unconstitutional, while the other two found it only borderline constitutional.) “The district judge’s deprecatory and often antagonistic attitude towards the defense is evident in the record from the very beginning,” the court wrote.

Despite the “sufficient evidence” of a crime under the anti- riot provision, the government declined to retry the case. “[The trial] really did bring disrepute on the judicial system,” said Greene, the Sun-Times reporter. At the end of it, Jerry Rubin tried to gift Judge Hoffman with a copy of his book. The inscription read, “Judge, you radicalized more people than we ever did.”