The Killing of Fred Hampton

Daniel Hautzinger

December 4, 2019

Independent Lens: The First Rainbow Coalition airs Monday, January 27 at 10:00 pm

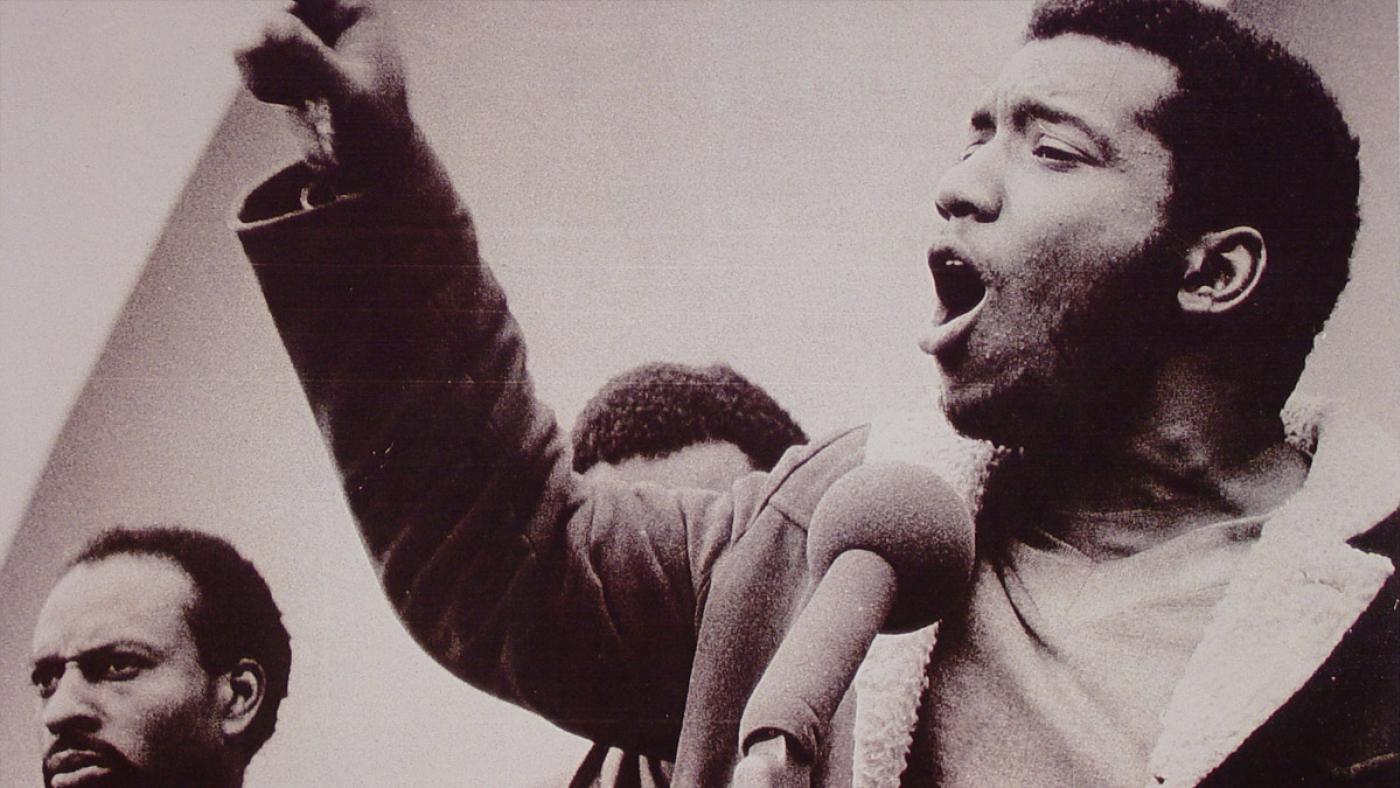

Fred Hampton did a lot in a single year. When the Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party was established on the West Side of Chicago in 1968, he became its chairman. Under his leadership, the militant, somewhat Marxist Panthers, who were known for carrying firearms in their home state of California, filled in the gap in social services in disadvantaged neighborhoods, offering free hot breakfasts for children and opening a network of clinics in North Lawndale and other neighborhoods. He taught the Young Lords, a Puerto Rican gang-turned-human rights organization, about activism and community organizing, and brokered an alliance between the Panthers, Young Lords, and the poor white Appalachian Young Patriots to organize against poverty and lack of services; the alliance became known as the Rainbow Coalition.

“We’re gonna fight fire with water,” Hampton said. “We’re gonna fight racism not with racism, but we’re gonna fight with solidarity… We’re gonna fight their reactions with all of us people getting together and having an international proletariat revolution.”

And the Panthers’ arsenal, their penchant for calling police “pigs,” and Hampton’s promise that, if police and others “step outside the bounds of legality into the bounds of illegality, then we’ll blow their brains out, if they bother the people,” scared the powers that be so much that the FBI, Cook County State’s Attorney’s office, and Chicago police all worked against him: investigations suggest that the three organizations conspired to murder him, 50 years ago.

In the early morning of December 4, 1969, fourteen Chicago police officers came to 2337 W. Monroe St., where Hampton and other Panthers were staying. The official account given by state’s attorney Ed Hanrahan was that the police were fired upon by the Panthers when they tried to enter the home on a search warrant issued for possession of illegal weapons. They allegedly called three times for the Panthers to stop shooting and exit the house with their hands up before returning fire, killing Hampton and another Panther, Mark Clark.

This was the narrative Hanrahan and the city pushed via allies in the media. The Chicago Tribune published an exclusive offered by Hanrahan: photos purporting to show bullet holes left by the Panthers’ gunfire. Other journalists visited the house and concluded that the “bullet holes” were nail holes.

A week after Hampton’s death, WBBM-TV broadcast a recreation of the raid that reflected Hanrahan’s account and featured the policemen who participated in it re-enacting their roles. The program was offered to other television stations, but they refused to air it, given the stipulation that it air unedited and without interruption or comment.

Meanwhile, the Panthers sought to prove their own narrative. Bobby Rush and Chaka Walls, two Panthers, appeared on WMAQ during its noon newscast for a live interview the day of the raid. They claimed that the police went to the home intending to kill Hampton. They also said that Hampton was asleep in bed when he was killed. Panthers led tours of the bullet-riddled building to lend credence to their version of events.

That version was in large part confirmed by a federal grand jury investigation in which a ballistics expert concluded that the police had fired 99 bullets while the Panthers had fired one. The probe did not, however, recommend prosecution.

Hanrahan may have escaped indictment because of the involvement of the FBI – he could reveal the extent of that involvement if they tried to prosecute him. Eventually, the public came to learn that the Panther William O’Neal was an FBI informant and had drawn up a floor plan of the apartment where Hampton and Clark were killed. The FBI then handed that map to the state’s attorney’s office.

Hampton’s fears in the months leading up to his death that the FBI and the police were out to get him ended up being true. There had already been other shootouts between the Panthers and the Chicago police in 1969, after Mayor Richard J. Daley and Hanrahan declared a “war on gangs” in May of that year and deployed 1,000 additional police officers. Over the summer, a Panther was killed in a shootout; in November a Panther and two police officers were killed in another. The killing of Hampton and Clark brought to a close the dismal year in Chicago, which had also seen Panther leader Bobby Seale bound and gagged during a conspiracy trial related to protests at the 1968 Democratic National Convention, as well as violent protests by young activists in the “Days of Rage.”

Hampton’s son, Fred Hampton, Jr., was born weeks after his father’s death; his mother, Akua Njeri was in the building with Hampton when he was killed.

Hanrahan lost his bid for re-election in 1972. Bobby Rush was elected alderman in 1983, the same year that Harold Washington became Chicago’s first black mayor, thanks in part to a diverse base of supporters that had in some ways grown out of the Rainbow Coalition forged by Hampton fourteen years earlier. Rush, who became a U.S. Congressman in 1993, later said that the murder of Hampton and the outcry it caused could be directly linked to the election of Washington.

That same year as Washington’s election, the city of Chicago, Cook County, and the federal government paid Clark and Hampton’s survivors a $1.85 million settlement after they brought a civil suit. Still, no one who participated in the raid was convicted of a crime.

Unlike Rush, Hampton never got to move on to electoral politics. When he was killed, he was only 21 years old.

A film about Hampton called Jesus Was My Homeboy, produced by Black Panther director Ryan Coogler and starring Daniel Kaluuya as Hampton and Lakeith Stanfield as O’Neal, is in the works. [Note: That film eventually came out in February 2021 as Judas and the Black Messiah. Coogler produced, while Shaka King directed.]