The Chicago Librarian Who Created a Lauded Collection of African American History and Literature

Daniel Hautzinger

February 13, 2020

Just as a library can be more than a lending station for books but also a repository of history, a librarian can be not just a cataloger and recommender of volumes; she can be an historian. And the work of an historian can inspire people in the present: to better know themselves, to understand where they came from, to take pride in their heritage, to create future works that themselves inspire and become a part of history.

Vivian G. Harsh was a librarian who was also an historian, one who nurtured, collected, and disseminated African American history and literature on the South Side of Chicago at a time when few others did. Today, 60 years after her death, her work continues to bear fruit.

Harsh was the Chicago Public Library’s first African American branch head and the originator of a lauded collection of African American history and literature that contains everything from manuscripts by Langston Hughes and Richard Wright to the archives of Ebenezer Baptist Church and the personal papers of prominent Chicagoans such as Timuel Black—who grew up visiting Harsh’s library and remains involved in the management of the collection. Today housed at the Carter G. Woodson Regional Library in Washington Heights, the collection—the largest of its kind in the Midwest—is named in honor of its first collector: it is the Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection of Afro-American History and Literature.

Harsh was born in Chicago to a family described as “blueblood” by the Chicago Defender in its obituary for Harsh. (The obituary’s headline was “Historian Who Never Wrote.”) Her mother was one of the first female graduates of the historically black Fisk University in Tennessee; her father owned a saloon. She attended Bronzeville’s Wendell Phillips High School (which would later produce numerous other famous alumni, from Sam Cooke to the first Harlem Globetrotters) and began working for the Chicago Public Library as a junior clerk in 1909. After receiving a degree in library science and climbing the ranks of CPL, she was appointed the head of the new George Cleveland Hall Branch in 1932.

![Richard Wright and Vivian Harsh. Photo: George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives, [Box 9, Photo 018], Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Chicago Public Library Richard Wright and Vivian Harsh. Photo: George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives, [Box 9, Photo 018], Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Chicago Public Library](/sites/default/files/styles/pull-right/public/images/2020/02/12/hall018.jpg?itok=tcYbuxg3) Richard Wright and Vivian Harsh. Photo: George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives, [Box 9, Photo 018], Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Chicago Public LibraryBefore the opening of Hall branch, Bronzeville—and indeed, all of Chicago’s black neighborhoods—lacked a library, according to a 1991 Chicago Tribune article about the branch. To rectify that disparity, George Cleveland Hall, a black surgeon and community leader, convinced the philanthropist Julius Rosenwald to buy land at 48th Street and South Michigan Avenue and donate it to the city for a library. Rosenwald was a leader of Sears, Roebuck and Co. who helped build schools for African Americans throughout the South as well as YMCAs throughout the country, including one on Chicago’s Wabash Avenue that served Bronzeville.

Richard Wright and Vivian Harsh. Photo: George Cleveland Hall Branch Archives, [Box 9, Photo 018], Vivian G. Harsh Research Collection, Chicago Public LibraryBefore the opening of Hall branch, Bronzeville—and indeed, all of Chicago’s black neighborhoods—lacked a library, according to a 1991 Chicago Tribune article about the branch. To rectify that disparity, George Cleveland Hall, a black surgeon and community leader, convinced the philanthropist Julius Rosenwald to buy land at 48th Street and South Michigan Avenue and donate it to the city for a library. Rosenwald was a leader of Sears, Roebuck and Co. who helped build schools for African Americans throughout the South as well as YMCAs throughout the country, including one on Chicago’s Wabash Avenue that served Bronzeville.

The Wabash Avenue Y and George Cleveland Hall (who died before the library named after him was completed) played roles in another important part of Vivian Harsh’s life. In 1915, Hall and other community leaders met with the historian Carter Woodson at the Wabash Y to found the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History to support research into and education on the neglected field of African American history. (Woodson is known as the “father of black history.”)

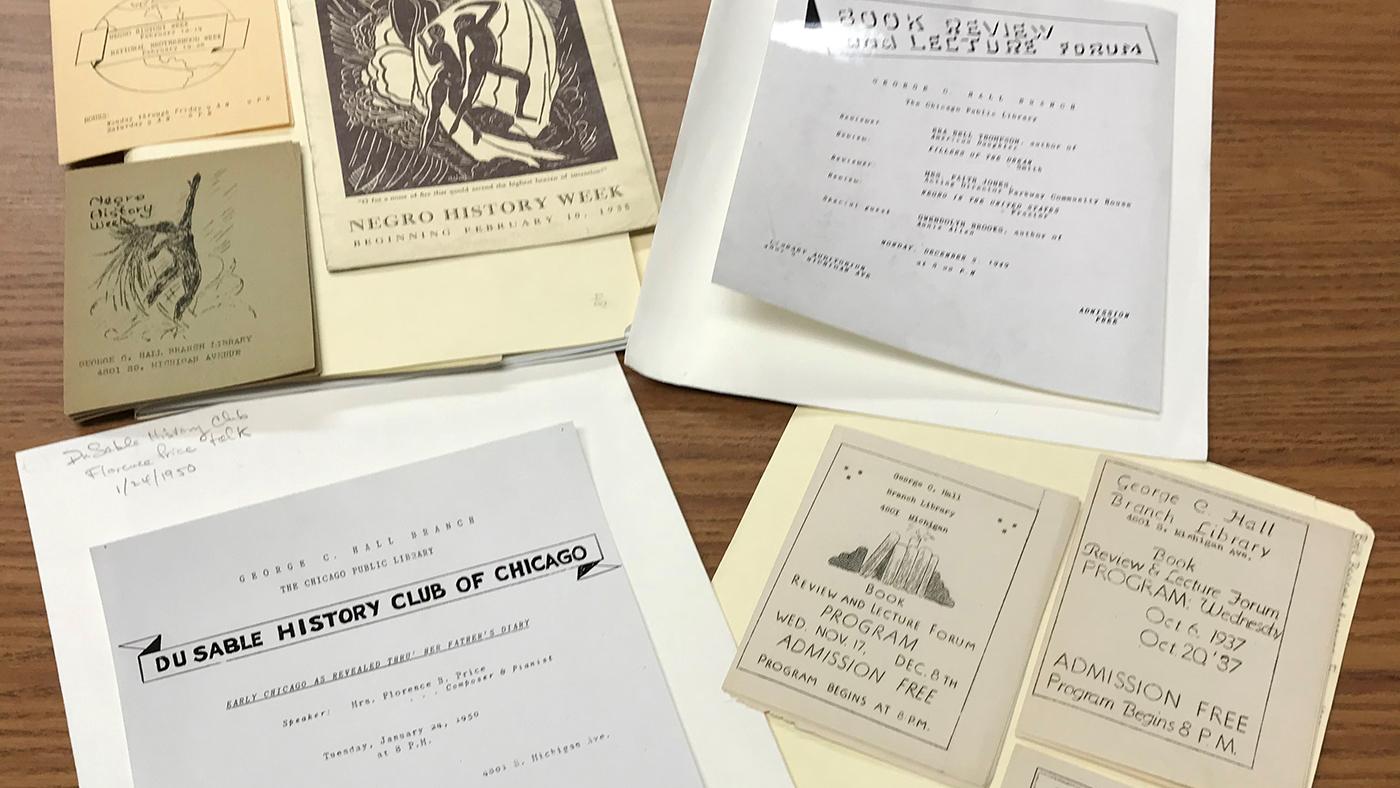

Harsh became an active member of the Association, using her position at Hall branch to promote its work and advance its goals. In February of 1926, the Association began celebrating Negro History Week, a precursor to today’s Black History Month, and Harsh hosted numerous programs relating to the Week throughout her tenure. She also began collecting books, manuscripts, and other materials relating to black history and literature, building up a “Special Negro Collection” that soon gained a reputation as one of the best in the country. John H. Johnson, the publisher of Ebony magazine, said the collection inspired him to develop his magazines, according to a 2007 Chicago Tribune article.

The collection helped make Hall branch into a gathering place for young black writers and intellectuals, as did Harsh’s Book Review and Lecture Forum, which hosted speakers such as Gwendolyn Brooks, Zora Neale Hurston, Alain Locke, and Richard Wright discussing and critiquing books. Many of those writers also contributed to Harsh’s collection. The manuscripts for several of Wright’s works are in the Harsh Collection, as is the manuscript and research for the WPA-sponsored “Negro in Illinois” project to which Wright contributed. Langston Hughes gave Harsh the manuscript for his autobiography The Big Sea, complete with edits in his own hand. Margaret Burroughs, the founder of the DuSable Museum of African American History, donated drafts of her poetry.

By the time Harsh retired from the library in 1958, the Special Negro Collection had grown to 2,000 books, in addition to various other materials—the fruit of years of Harsh’s hard work finding books, soliciting donations, and searching for the money to fund it all. Two years after retiring, in 1960, Harsh died.

A decade later, the Special Negro Collection was renamed in her honor, and in 1975 it moved from Hall branch to the newly constructed Woodson Library. Thus, Harsh and Woodson, who knew each other in life, also came together posthumously—a fitting meeting of two monumental figures in the research of African American history. Library staff continue to acquire materials for the Collection, such as the papers of the Congress of Racial Equality and prominent black Chicagoans. It now occupies 4,000 feet of shelf space. And the Collection remains available to the public to this day, ready to inspire the next John H. Johnson, or Gwendolyn Brooks, or Timuel Black.