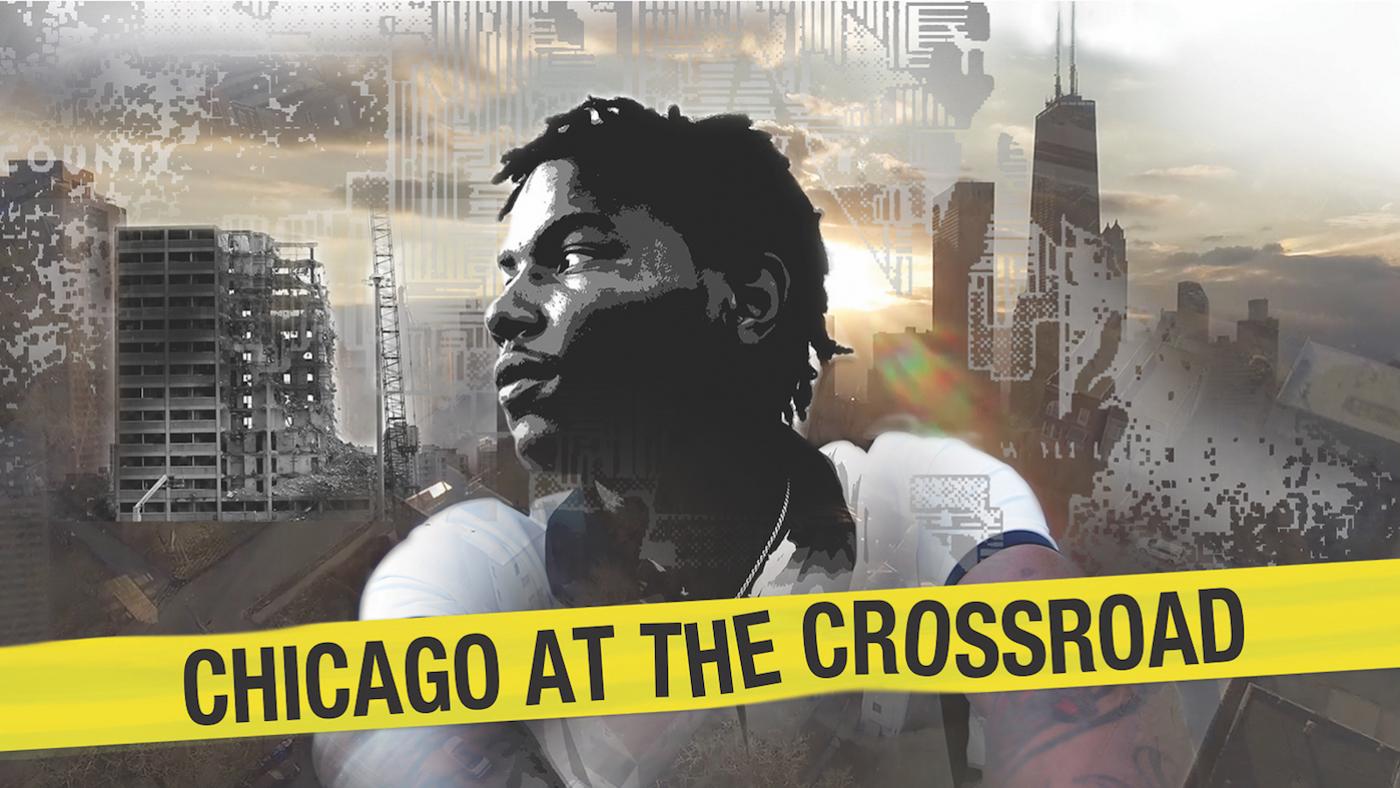

How the Failure of Public Housing Is Linked to Gun Violence in Chicago

Daniel Hautzinger

November 11, 2020

Chicago at the Crossroad first airs Thursday, November 12 at 8:00 pm and is available to stream. For another in-depth look at gun violence in Chicago, watch FIRSTHAND: Gun Violence, WTTW’s digital series recounting the stories of five individuals personally affected by it.

“You know the problem,” someone says about gun violence in Chicago in the new documentary Chicago at the Crossroad. “What is the solution?”

It’s a perpetual question that numerous people, community organizations, scholars, and policymakers are constantly trying to answer, doing their part to reduce gun violence and alleviate the disinvestment and inequality that is a cause of that violence. But finding a solution also means understanding the roots of the problem.

“I decided to look for some root causes of violence instead of just doing a documentary on the surface level topics around violence,” says Brian Schodorf, the writer, director, and producer of Chicago at the Crossroad. “The biggest thing that stood out was housing, because your housing will dictate every other aspect of your life, from school to food to violence exposure to your percentage of the possibility of actually committing a crime.”

Chicago at the Crossroad narrates the rise and fall of public housing in Chicago, from its beginnings in the postwar period to its failures and eventual destruction in the late 1990s and 2000s. “When you start to look at housing, you have to look at the deeply entrenched racial suppression policy tactics that were used in many Northern cities to segregate African Americans into certain pockets of the city. And public housing really exemplifies all of those things in one set of policies.”

As public housing deteriorated under poor stewardship and was widely condemned, the government eventually decided to simply tear it down, making way for profitable developments in some places like Cabrini Green, with its proximity to downtown. But a comprehensive replacement never materialized.

“You still have these vacant lots [where public housing used to stand],” says Schodorf. “They still have large areas that were earmarked for mixed-income redevelopment, meaning bring back the residents. And that didn’t happen. A very small percentage of families in public housing who were displaced actually moved back to the original sites. [There was] a billion dollar plan, and it didn’t happen.”

That failure to provide housing also had a personal cost for the families that lost all traces of the home they grew up in, whatever their complicated feelings about it. “What’s really heartbreaking about the whole thing is that families who have lived in public housing for generations have really lost a lot more than we realize on the surface,” Schodorf says.

Section 8 housing vouchers, which provide assistance in paying rent, are meant to fill in the gap left by the loss of public housing, but have had the effect of continuing to concentrate poverty in low-opportunity communities. “When you look at Section 8 housing—there are lots of problems with it—they incentivized the for-profit model,” Schodorf says.

“Secondly, public housing was a very social service-rich environment. They knew where to find you; you knew where to find the services: for childcare, doctors, schools, all those things. So now you have folks who are out in different communities and that lifeline isn’t there anymore, something you see especially with this pandemic.”

There are community organizations that try to step in and fill the gaps in social services, like the Firehouse Community Art Center in North Lawndale, which aims to engage young adults in the arts to keep them from getting caught up in violence. The Firehouse is featured in Chicago at the Crossroad as the documentary follows one young man and his struggle to find opportunity.

“If you look at community-based institutions like the Firehouse, they are institutions who are boots on the ground, and they provide many services, including mentorship, counseling for PTSD, drug counseling, trauma counseling, job training,” Schodorf says. “They are trying to get these young men who are at risk of committing crimes or being victims of crimes to reset their train of thought, and trying to get them to look in another direction, to live their lives where it’s not on the street, not drugs, not violence. That is definitely the most effective way to reduce the shootings.”

“I think Chicago has the potential to set an example for how to reduce the violence in urban areas,” Schodorf says. “You have to bring revitalization into the neighborhoods, and we’re not just talking about gentrification. We don’t want to continue to displace people and push people out, because that’s not the solution. You see revitalization in some of the neighborhoods where there are community gardens, garden centers, mural programs where they’re putting art across the community and things like that.”

“I think the film shows how people can get involved and what works as far as making a positive impact,” Schodorf says. “People need to be educated about the historical factors that went into creating and segregating many of our cities, and show people what the root causes are so they don’t have all these preconceived notions.”