The Influential Plan That Sought to Make Chicago Beautiful

Daniel Hautzinger

November 19, 2020

Chicago from the Air, which lets you see the fruits of the Burnham Plan from a whole new angle is available to stream, along with additional content, at wttw.com/air.

“At no period in its history has the city looked far enough ahead,” admonished Daniel Burnham and Edward H. Bennett in the 1909 Plan of Chicago. Chicago’s astonishing growth over the previous seven decades—from about 4,000 people to more than two million—had outpaced the ability to plan its expansion in an orderly fashion. “Men are becoming convinced that the formless growth of the city is neither economical nor satisfactory,” they wrote. Therefore, “practical men of affairs are turning their attention to working out the means whereby the city may be made an efficient instrument for providing all its people with the best possible conditions of living.”

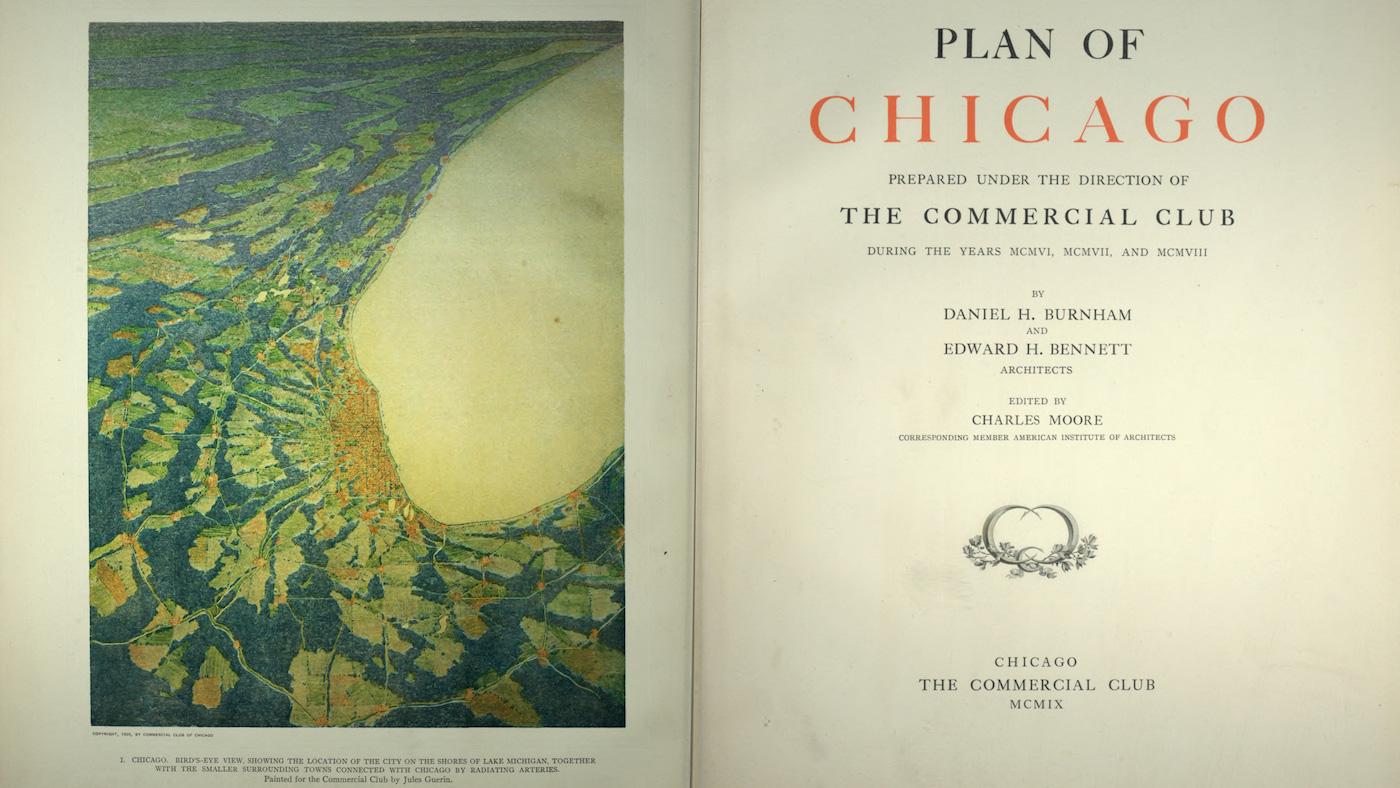

Burnham and Bennett had been commissioned to create a plan for Chicago in 1906 by the Commercial Club of Chicago, whose civic-minded membership included many of the city’s most prominent “practical men of affairs.” Businessmen like George Pullman, Marshall Field, George Armour, and Burnham himself sought to promote Chicago’s development as well as various contemporary reforms through the Commercial Club, and the Plan for Chicago incorporated their goals into one grand vision for the city.

At base, the Plan sought to make Chicago beautiful: attractive, rational, navigable, accessible, full of parks and monumental buildings that would inspire moral uplift and civic pride amongst the growing number of citizens who made it their home. It’s not for naught that the Plan is considered an epitome of the City Beautiful movement, a prevailing urban planning philosophy in America at the time.

Burnham was a leading proponent of City Beautiful, which saw its first major realization in the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, for which he served as Director of Works. The Exposition’s stately buildings and landscaped grounds on the city’s southern lakefront were significant inspirations behind the commissioning of the Plan—city leaders wanted to emulate the success of the Exposition across the city. “The World’s Fair of 1893 was the beginning, in our day and in this country, of the orderly arrangement of extensive public grounds and buildings,” the Plan boasts.

(Burnham was not shy in commending himself in the Plan; its introductory survey of cities “ancient and modern” includes numerous city plans he had helped develop: Cleveland, Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and the Philippines’ Manila and Baguio. To be charitable, he had clearly put a lot of thought into urban planning.)

The 'Plan of Chicago' aligns with the "City Beautiful" movement that influenced urban planning in America around the turn of the century. Image: Wikimedia Commons

The 'Plan of Chicago' aligns with the "City Beautiful" movement that influenced urban planning in America around the turn of the century. Image: Wikimedia Commons

The Plan hoped to harness the “spirit of Chicago” that had made the Exposition possible to improve the city as a whole, and many of its recommendations sprang directly from the Fair. The beauty of Jackson Park, created for the Exposition by Central Park designer Frederick Law Olmsted, propelled a desire to connect it and downtown’s Grant Park with an uninterrupted park along the lakefront.

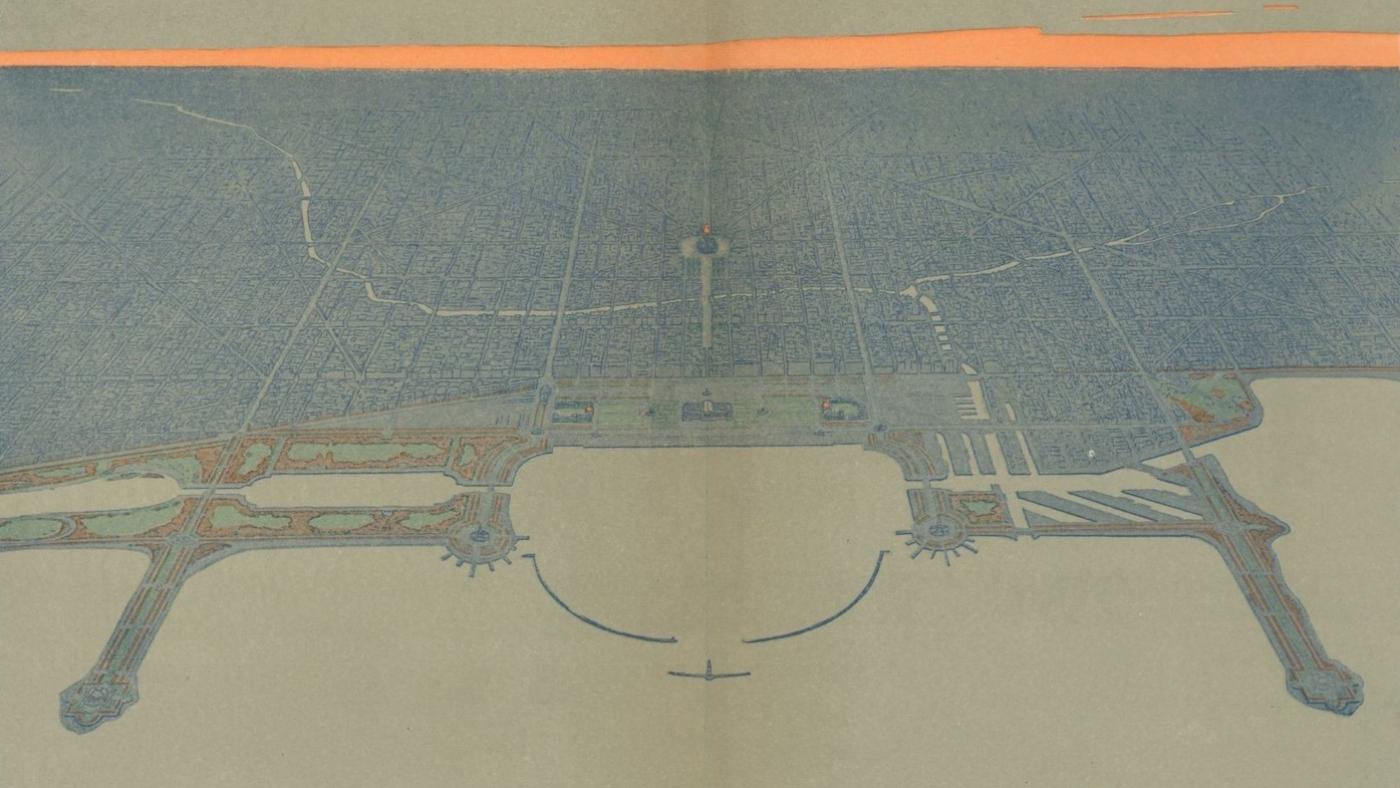

The lakeshore “should be treated as park space to the greatest possible extent,” the Plan proclaims. “The Lake front by right belongs to the people.” While Burnham’s vision for the lakefront wasn’t fully realized—Northerly Island is the only one of a series of proposed strips of parkland out in the lake, and the city never built artificial islands along the north shore—his desire for the lakefront to be a public park came true. It’s perhaps the most lasting legacy of the Plan.

In addition to a lakefront park, the Plan called for a series of parks and parkways throughout the city. “All of us should often run away from the works of men’s hands and back into the wilds, where mind and body are restored to a normal condition, and we are enabled to take up the burden of life in our crowded streets and endless stretches of buildings with renewed vigor and hopefulness,” the Plan says, echoing prevailing beliefs about the salutary effect of nature on crammed-in urban residents.

Presciently envisioning Chicago as the center of a vast cooperative conurbation, Burnham and Bennett also recommended establishing forest preserves as well as parks in the suburbs. “From Kenosha on the north, around to De Kalb [sic] on the west, and thence to Michigan City on the south, all roads lead to Chicago; and this entire region might well be included in a metropolitan area within which large parks shall be located, improved and maintained at joint expense.”

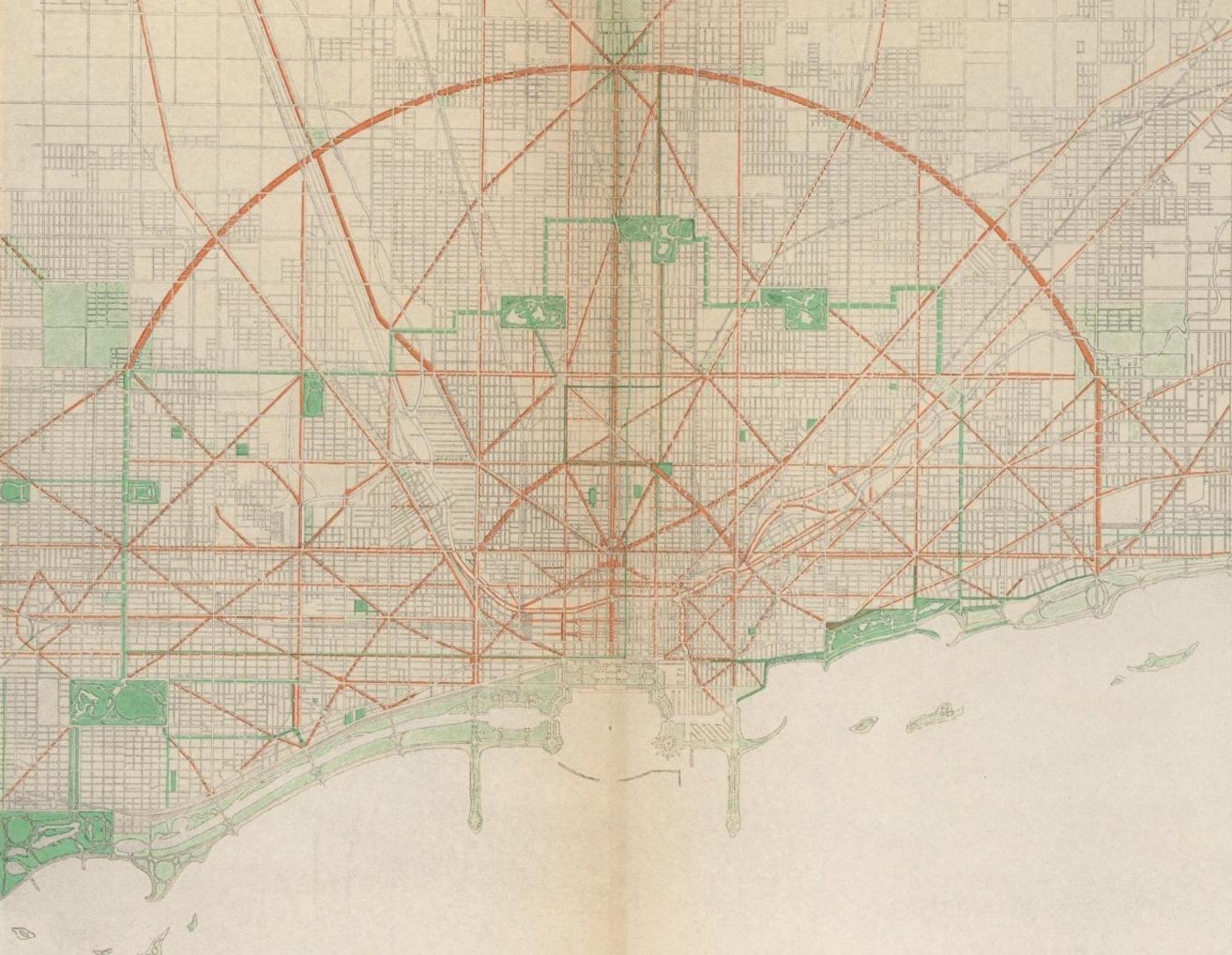

A major focus of the 'Plan' was on improving circulation through the city, including via an extensive grid of streets. Image: Typ 970U Ref 09.296, Houghton Library, Harvard University/Wikimedia Commons

A major focus of the 'Plan' was on improving circulation through the city, including via an extensive grid of streets. Image: Typ 970U Ref 09.296, Houghton Library, Harvard University/Wikimedia Commons

To allow for easy transportation and commerce throughout this massive region and within the city, Burnham and Bennett recommended a radial system of encircling highways, an orderly grid of streets cut through by diagonals and ring roads, and improved railway terminals and lines. (Chicago’s grid and diagonal streets were mostly already in place.) They even detail how wide a street should be and what type of pavement it should have, depending on its use.

The Plan’s final major recommendation concerned “the development of centers of intellectual life and of civic administration.” Grant Park was to be the intellectual center, with the Art Institute (already there), the Field Museum, and a library situated in landscaped gardens. A yacht harbor would extend the length of the park, with recreation piers extending into the lake on the north and south—like Navy Pier today. Athletic fields and other places for exercise would be located in a “great meadow” south of the park, where Soldier Field now stands. More recreation along the water should eventually be developed along the downtown stretch of the river, the Plan says; now we have the Riverwalk.

Burnham and Bennett situated the civic center of the city at Congress and Halsted—about where Greektown is today. City, county, and federal administration buildings would all reside there in monumental splendor, like the White City of the World’s Columbian Exposition.

While that never happened, many of the Plan’s principles were incorporated into the city as it continued to grow, thanks in part to what it lauds as the people of Chicago’s “constant, steady determination to bring about the very best conditions of city life for all people, with full knowledge that what we as a people decide to do in the public interest we can and surely will bring to pass.”