Ernest Hemingway's Youth in Oak Park and Chicago

Daniel Hautzinger

February 23, 2021

The new, three-part Hemingway from Ken Burns and Lynn Novick premieres on WTTW and PBS April 5-7. Watch a conversation about Hemingway's childhood with Burns, Novick, author Tim O'Brien, and Verna Kale. Find more at wttw.com/hemingway.

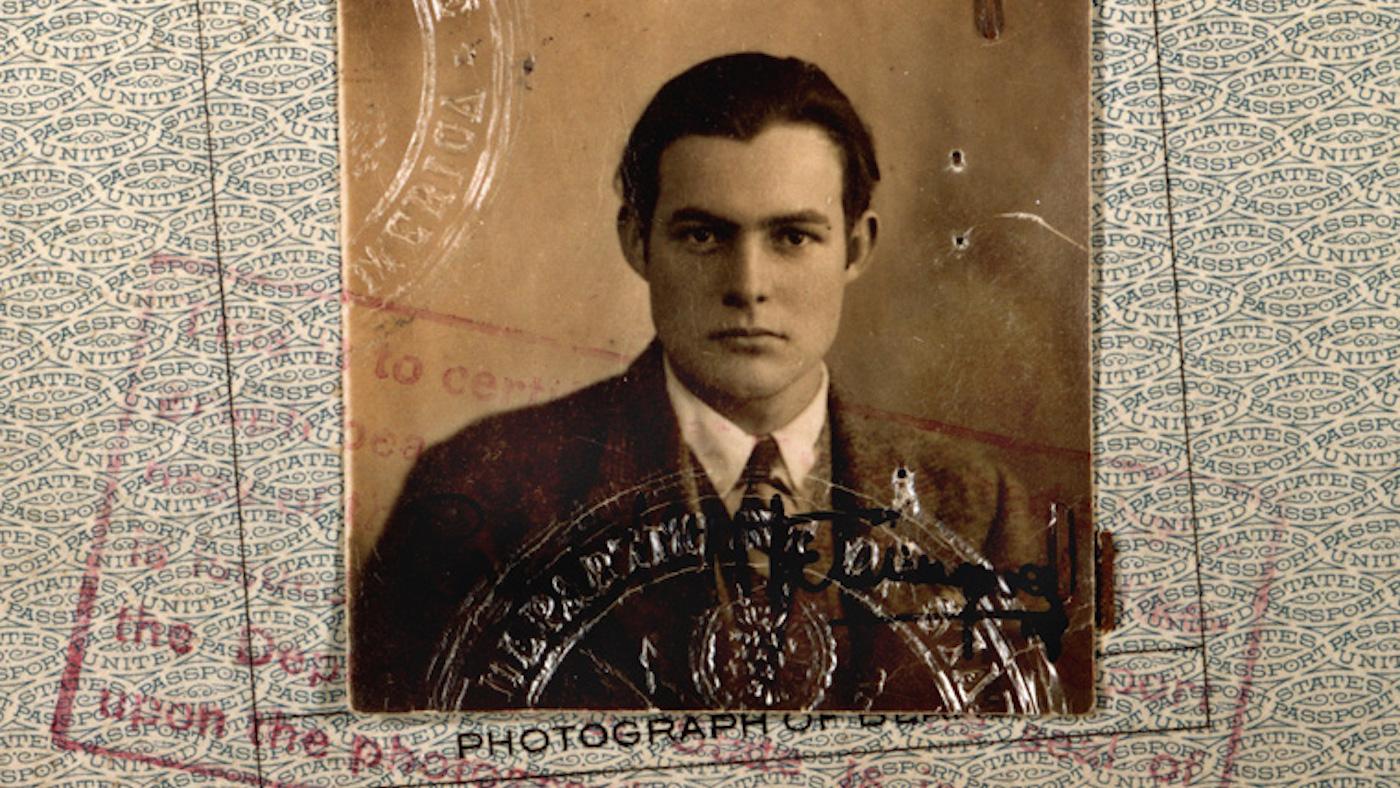

Ernest Hemingway’s life and fiction were filled with extraordinary experiences and locales: World War I in Italy, Paris at the height of the Jazz Age, bullfighting in Spain, safaris and plane crashes in Africa, drinking and fishing in Cuba. But he was born in the solidly middle-class, Midwestern, middlebrow Chicago suburb of Oak Park—a place he liked to portray as staid and stuffy. (The description “wide lawns and narrow minds” is frequently attributed, seemingly incorrectly, to Hemingway.) As the Newberry Library’s Liesl Olson writes, “Hemingway liked to present Oak Park as a place in which he overcame the Victorian values of his parents and then left as soon as he could…”

“Turn-of-the-century, affluent suburban life is basically the world that he was born into,” says Verna Kale, the author of a biography of Hemingway, a co-editor of his letters, and an editor of Teaching Hemingway and Gender. “His father was a physician and his mother gave music lessons, and she earned quite a bit of money as a music teacher.”

Hemingway’s mother ensured her children had a background in the arts. Hemingway learned to play the cello, was encouraged in the visual arts, and wrote for his high school paper as well as his own stories. The family spent summers in Michigan. “He pretty much had a really nice childhood,” Kale says.

But Hemingway was eager to leave Oak Park behind, going first to Kansas City to work as a reporter and then to Italy to drive an ambulance during World War I. (The ship he took to Europe was coincidentally called Chicago.) He was wounded early in his service and spent several months convalescing in Milan before returning to Oak Park around the age of 20.

Hemingway family portrait. From left to right: Ursula, Clarence, Ernest, Grace, and Marcelline Hemingway. October 1903. Image: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

Hemingway family portrait. From left to right: Ursula, Clarence, Ernest, Grace, and Marcelline Hemingway. October 1903. Image: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

“When he comes back from the war, he definitely has changed,” says Kale. “He wants to get out into the world and see a little bit more. Going back home is always so hard when you’re that age. We have to extrapolate a little bit from the fiction here”—stories like “Big Two-Hearted River” and “Soldier’s Home”—“but he may have felt that no one really understood what he had been through. I imagine that he got home from the war and felt like he didn’t fit in anymore.”

Hemingway also seems to have felt that his ambitions had outgrown his suburban birthplace. “He wanted to do something great,” says Kale. “He wants to write, he’s sending stories off to the Saturday Evening Post and getting rejected. He’s applying for jobs in advertising and getting rejected.”

Soon he had moved to Chicago, earning money by writing for a Toronto newspaper. It was in the city that he first began to experience a literary life. “I think that meeting Carl Sandburg and Sherwood Anderson, and getting a glimpse of that Chicago literary scene, opened up his mind a little bit and made him realize that, ‘This is a different world than the one that I’m coming from.’ ”

That sentiment might explain more than anything else Hemingway’s distancing from his Oak Park childhood: he had found the world he wanted to be in, and it was nothing like the one from which he came.

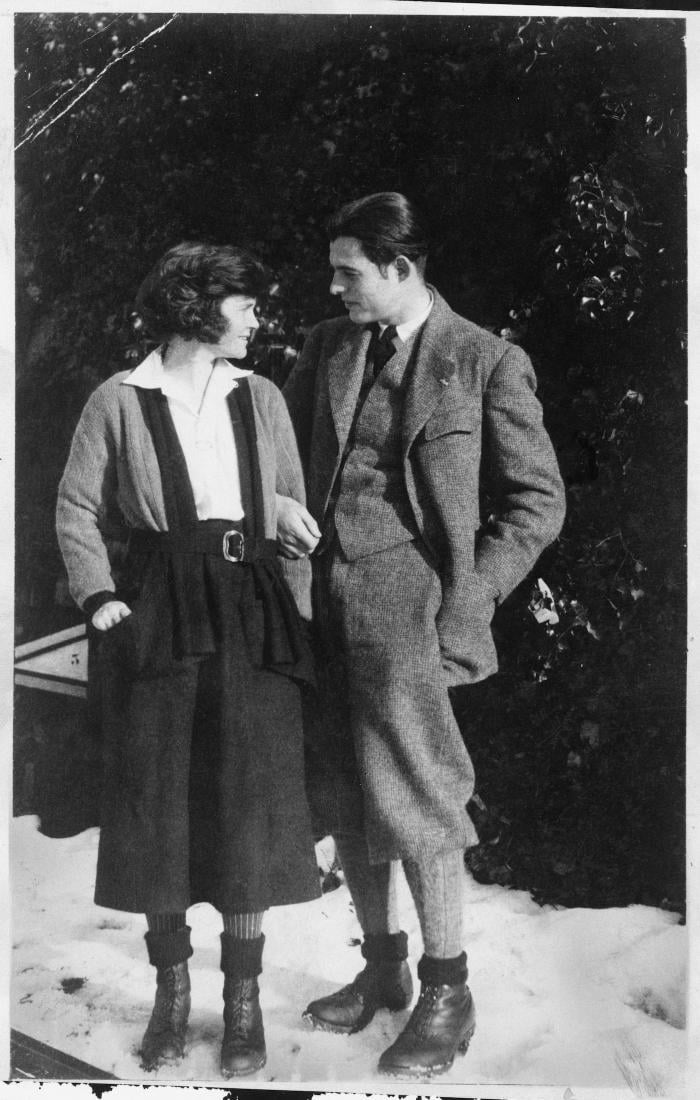

Ernest Hemingway and first wife, Hadley Richardson, in Chamby, Switzerland, 1922, the year after they left Chicago for Europe. Image: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, BostonHemingway’s sojourn in Chicago also helped launch him on one of the most celebrated—and integral—parts of his life. He wanted to return to Italy with his new wife Hadley Richardson, but Sherwood Anderson convinced him to instead go to Paris after a year and a half in Chicago, giving him letters of introduction to such important influences and connections as Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound.

Ernest Hemingway and first wife, Hadley Richardson, in Chamby, Switzerland, 1922, the year after they left Chicago for Europe. Image: Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, BostonHemingway’s sojourn in Chicago also helped launch him on one of the most celebrated—and integral—parts of his life. He wanted to return to Italy with his new wife Hadley Richardson, but Sherwood Anderson convinced him to instead go to Paris after a year and a half in Chicago, giving him letters of introduction to such important influences and connections as Gertrude Stein and Ezra Pound.

Hemingway “hadn’t had very much luck in actually publishing anything” yet, says Kale. But “Sherwood Anderson met him socially and saw the potential there and basically directed him to where he needed to be.”

While Hemingway never returned to Chicago or Oak Park for any significant portion of the rest of his life, he did maintain connections to his birthplace when he went to Paris. “When he first gets to Paris, he’s writing back home and telling his parents about his success and about the people he’s meeting,” says Kale. “He’s doing a little bit of name-dropping and possibly even exaggerating his early success because he wants his parents to be proud of him.”

“I think it’s so sweet that his father ordered multiple copies of his first book,” she continues. “People tend to focus on the fact that his father hated the kind of obscene stories that Hemingway was writing. But you have to kind of cut them some slack, because the stuff that he was writing was really innovative. Of course they hated it! Just because they didn’t get what he was doing doesn’t mean they didn’t love him or that they weren’t proud of him.”

Shocking—and perhaps also titillating—people like his parents may have been part of Hemingway’s goal. Liesl Olson, of the Newberry, argues in her book Chicago Renaissance: Literature and Art in the Midwest Metropolis that Hemingway was addressing middle-class Midwestern women as epitomized by the popular Chicago Tribune critic Fanny Butcher in his early work, wanting to scandalize them but also enjoy the conventional approval as well as mass-market success they offered.

Hemingway even struck up a correspondence with Butcher, whose recommendations offered access to a large audience. “Hemingway is always full of these contradictions,” says Kale, “because I think he wanted those good reviews, he wanted that acceptance, but at the same time he felt like he was doing something beyond their understanding. If they liked his stuff, sometimes he would say it was for the wrong reasons, or they didn’t really understand what he was trying to do.

“There’s definitely a conflict there between Hemingway the conservative Midwestern guy and Hemingway the modernist expatriate world traveler. There is still a certain amount of the suburban Chicago guy even when he is in the Latin Quarter of Paris.”

Those contradictions are one of the main attractions of Hemingway for Kale. “There’s just limitless ways to read him. And they’re not necessarily all the ways that he would maybe want us to read him, but his work is incredibly elastic, and it just holds up to anything you want to bring to it personally,” she says. “He wasn’t really writing for a particular purpose. He was just trying to write as well as he could and put the real world into his work in a way that would last.

“He just crafted the work so that it will hold anything that you want to bring to it.”