The Man Who Shaped Both the Cubs and the Sox

Daniel Hautzinger

March 30, 2021

After a year in which seasons were drastically reduced and games were played in front of empty stands, Major League Baseball returns on April 1 to a full season and limited live fans. Chicago’s stadiums will be limited to 20% capacity, with the Cubs home opener against the Pittsburgh Pirates on April 1 and the Sox home opener against the Kansas City Royals on April 8.

If Bill Veeck were alive, you can be sure he would have something outrageous planned after such a trying year. The Cubs employee and owner of the White Sox and Cleveland Indians was a flamboyant promoter, known for boosting lagging teams with extravagant hijinks. Some innovations, like the ivy at Wrigley Field, players’ names on their uniforms, and the exploding scoreboard, were lasting and widely adopted. Others—sending out a 3’7” batter with a tiny strike zone, letting the fans call plays instead of the dugout, Disco Demolition Night—were (probably deservedly) one-offs.

“Regardless of what they say, all the players, even the veterans, get a great thrill out of the opening day,” Veeck said on WTTW’s Time Out sports program in 1984, before recalling several of his opening day gimmicks. “The skydivers: the first time I used them in Cleveland, they landed in Lake Erie. When we used them in Chicago, they landed in Armour Park, not Comiskey Park. It took twenty years to get them onto second base.”

(You can watch several of Veeck’s Time Out commentaries in a montage aired on WTTW’s Chicago Tonight the day after his death in 1986, as well as a clip from the 1985 WTTW program Veeck: A Man for Any Season, below.)

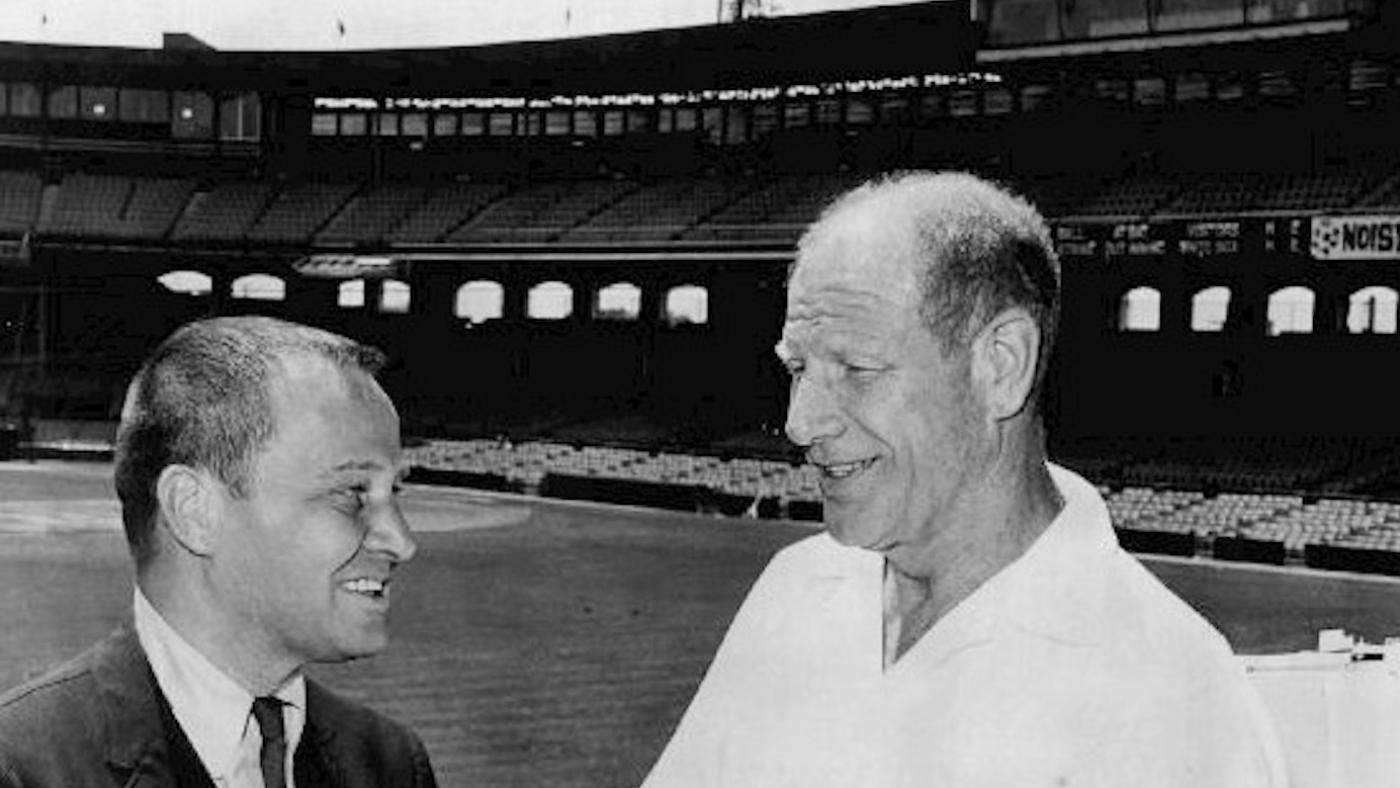

Bill Veeck suffered a lifelong injury to his leg while serving in the Marines. Photo: Wikimedia CommonsVeeck grew up in baseball, and, like his skydivers, he had misfires as well as successes. He was the son of William Veeck, Sr., a sportswriter who became president of the Cubs.

Bill Veeck suffered a lifelong injury to his leg while serving in the Marines. Photo: Wikimedia CommonsVeeck grew up in baseball, and, like his skydivers, he had misfires as well as successes. He was the son of William Veeck, Sr., a sportswriter who became president of the Cubs.

Veeck, Sr. built what many baseball historians consider to be the best team ever—the 1929 Cubs—and also modernized the franchise, adding a second deck to Wrigley Field and pioneering radio broadcasts of games. He also appointed the first woman to an executive level in the major leagues.

Veeck, Jr., born in the Chicago area in 1914, spent a lot of time at Wrigley Field, working odd jobs there beginning in his early teens. He’s the one who planted the iconic ivy on the outfield walls.

But he had big aspirations, so he went north with former Cubs player and manager Charlie Grimm to buy the minor league Milwaukee Brewers in 1941. The team was in last place. And yet Milwaukee served as a successful training ground for Veeck. He began testing out promotional efforts to boost attendance, sprucing up the stadium, giving away surprise prizes (including live animals), and scheduling morning games for night shift workers to attend. Plus, he improved the team. Under him, the Brewers won three pennants in a row.

While owning the Brewers, Veeck suffered an injury when a recoiling anti-aircraft gun smashed his leg during service in the Pacific in World War II. It would eventually be amputated and plague him the rest of his life—he underwent more than 30 medical operations and walked with a wooden leg.

Famously casual and a friend of the everyday fan (his Baseball Hall of Fame plaque names him “A Champion of the Little Guy”), Veeck was known to sometimes take the leg off in public. He never wore a necktie, removed the door from his offices, and was a philosophical gadabout. “He consumed books the way he took down beer: voluminously and delightfully,” WTTW’s John Callaway said in an episode of Chicago Tonight devoted to Veeck after his death. He supported literacy efforts, was against handguns, vocally anti-Reagan, and marched in Selma for civil rights.

In his autobiography, Veeck as in Wreck, he claimed to have tried to buy the Phillies in 1942 with financing from the Harlem Globetrotters’ Abe Saperstein. Veeck planned to stock the team with Black players and break the color line, but was stymied by league leaders. The veracity of the anecdote is debated, but Veeck did eventually help integrate the major leagues after he sold the Brewers then bought the Indians in 1946, becoming the major leagues’ youngest chief executive at 32.

Cleveland had not won a pennant since 1920, but Veeck quickly boosted attendance, setting a record in 1948, when the team won the World Series. They won with the help of Larry Doby, whom Veeck signed as the first Black ballplayer in the American League and who made his debut months after Jackie Robinson; and Satchel Paige, another player Veeck brought in from the Negro Leagues.

Veeck sold the Indians in 1949, in part because he needed cash for his divorce from the circus performer Eleanor Raymond. (Veeck was often likened to the circus entrepreneur P.T. Barnum.) In 1950, he married Mary Frances Ackerman, a publicist who would gamely help him promote his teams for the rest of his life. The following year he bought the St. Louis Browns.

The Browns were the poor loser to the Cardinals for fans and acclaim in the smallest two-team market. Visiting teams complained that their share of tickets didn’t even cover travel expenses. Veeck deployed some of his most outlandish schemes, which boosted attendance some—but not enough, partly because the team itself never improved.

He ended up selling the Browns’ park to the Cardinals to boost their unworkable budget, then selling the team itself to a Baltimore group, to become the Orioles. He had tried to move the franchise to Baltimore himself, but the other league owners, disapproving of his salesmanship and antics, had blocked the transfer until he sold.

Searching for an opportunity to rejoin baseball, Veeck found it in the White Sox. In his first year owning them, 1959, they won the American League pennant, going to the World Series for the first time since the “Black Sox” in 1919; the next year they broke Chicago’s attendance record. Yet Veeck’s incessant smoking and ill health were catching up to him, and doctors urged him to retire, so he sold the team in 1961 and retired to Maryland.

After a decade and a half of writing books and columns and trying to revive a failing racetrack (he always went for underdogs), he returned to his hometown a savior in 1975. The White Sox were being sold, and would most likely be transferred to Seattle. Against the resistance of other team owners—it took two separate votes to approve the sale—Veeck cobbled together investors to buy the team and keep it in Chicago.

As usual, Veeck made some popular choices—introducing Harry Caray singing “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” during the seventh inning stretch—and some disastrous ones—dressing the players in shorts and green-lighting his son Mike’s Disco Demolition Night idea.

But the dawn of free agency, which Veeck supported on behalf of ballplayers’ independence, and the exploding salaries it engendered, which he disliked, outpaced Veeck, whose budget was always thin. Once again in ill health and lacking money, Veeck sold the team in 1981. His chosen successor was rejected by the other owners, and Jerry Reinsdorf and Eddie Einhorn instead bought the team. When Einhorn said he and Reinsdorf would make the Sox high class at their first press conference, Veeck thought the comment was directed at him. He never went to Comiskey again.

Instead, he returned to his first ballpark, Wrigley Field, where he could be surrounded by his beloved regular-guy fans on the bleachers. “This is the best ballpark in the country,” he said on WTTW’s Time Out. “It is the one ballpark in which the fans are an absolute part of the game, a participant rather than spectators.” That was what Veeck always wanted.