An Exploration of Native American History in Chicago with Geoffrey Baer

Geoffrey Baer

November 29, 2021

Native Americans are often talked about in the past tense, including in Illinois and Chicago. That’s in large part because of the wholesale removal of Native tribes and nations from their homelands westward by treaty with the United States government as well as a concerted effort by the government to destroy Native traditions, culture, and languages via such dehumanizing methods as “civilizing” boarding schools—“kill the Indian, save the man,” the founder of one such school said.

But Chicago is home to the largest population of Native Americans in the Midwest and the second largest population east of the Mississippi River, according to a report from the University of Illinois at Chicago. “We’re still here,” Heather Miller, the executive director of Chicago’s American Indian Center, the oldest “urban Indian” center in the country, told WTTW in 2018. “We’re still very much connected to this land and to our history.”

Here are some sites that contain vestiges of that history as well as demonstrate the ways in which contemporary Native Americans continue to shape the city.

By the way, you can learn about even more of the Indigenous history of Chicago and Illinois in my new special Beyond Chicago from the Air, which premieres Wednesday, December 1 at 7:30 pm on WTTW and at wttw.com/beyondchicago.

Place Names

The Indigenous history of this country is hiding in plain hearing, in the names of everything from the Chicago River and city itself (Checagou is Algonquian for the pungent leeks that grew on the riverbank) to states (Illinois comes from the name of a Native American people, Michigan from an Ojibwe word for “large lake”) and streets. To name just a few: Menomenee Street, Milwaukee Avenue, Ottawa Avenue, Sangamon Street, Washtenaw Avenue, Winnemac Avenue.

Indian Trails

Rogers Avenue on Chicago's North Side follows the so-called Indian Boundary established in the Treaty of 1816. Image: WTTW

Rogers Avenue on Chicago's North Side follows the so-called Indian Boundary established in the Treaty of 1816. Image: WTTW

Long before European settlers came to the Chicago region, it was home to the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, Miami, and other Native American tribes and nations. Faint evidence of the trade they conducted around the mouth of the Chicago River remains in streets that cut across Chicago’s grid, following former Native American trails. Ridge Avenue, Lincoln Avenue, Clark Street, Archer Avenue, Ogden Avenue, and Vincennes Avenue are all examples.

Another diagonal street, Rogers Avenue, follows not a route used by Native Americans but a line meant to keep them out: the so-called Indian Boundary, established by the Treaty of 1816 between the U.S. and the Potawatomi Nation. This demarcation prohibited Native Americans from living near the Chicago River, and ran through what is now Indian Boundary Park in West Ridge before becoming Forest Preserve Drive and hitting Indian Boundary Golf Course.

Kittahawa

In the late 1770s, a Potawatomi woman named Kittahawa built a home on the north bank of the Chicago River with her husband of French and African descent, Jean Baptiste Point DuSable, becoming the first known permanent settlers there. They ran a thriving trading post near what is now the DuSable Bridge carrying Michigan Avenue over the Chicago River, where a bust of DuSable memorializes him. Their success was due in part to Kittahawa’s ability to form connections between Native Americans in the area via her kin networks and translation skills. By the time they sold their property in 1800, they had built up a sizable estate.

Kittahawa was not the only one to facilitate trade between Native Americans and Europeans in the region. Métis, people of mixed European and Native American ancestry, also often served as mediators, especially in the fur trade.

Fort Dearborn

As more and more European settlers, drawn in part by trade, moved onto Native American lands in the Great Lakes region, military conflict with Native tribes grew more frequent. The U.S. acquired the land at the mouth of the Chicago River in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville and began constructing a fort there in 1803.

In 1812, American forces evacuating Fort Dearborn as a result of the War of 1812 against the British were attacked along the lakefront by a group of Potawatomi, who won the battle. They burned down the fort, winning a brief reprieve from European settlement, but a new fort was built in 1816. It then served as a center for a war against the Sauk warrior Black Hawk who had by all accounts peacefully tried to reclaim land in northwestern Illinois in 1832. But he and his followers were attacked by a militia and government troops. The defeat of Black Hawk led to the final ceding of Potawatomi lands around Chicago in an 1833 treaty. Chicago was incorporated as a town that year.

American Indian Center

The original location of the American Indian Center was on Wilson Avenue in Uptown

The original location of the American Indian Center was on Wilson Avenue in Uptown

With most Native Americans removed from the region, Chicago lacked a significant Indigenous presence for the next 120 years or so. But in the 1950s the federal government began ending federal recognition of many tribes and relocating Native Americans to cities from reservations in an effort to force them to assimilate to the dominant culture. Because many Native Americans struggled to find work and adapt to urban life, the American Indian Center was founded to offer social services in 1953. It is the oldest “urban Indian” center in the country. Originally located in Uptown, the American Indian Center is now in Albany Park at Kimball Avenue and Ainslie Street.

First Nations Garden

Not too far from the American Indian Center is the First Nations Garden, at Pulaski Road and Wilson Avenue. It was established in 2018 by the Center and the Chi-Nations Youth Council in partnership with the city of Chicago, and is meant to serve as a healing space for Chicago’s Native community as well as an educational center for non-Native people.

Effigy Mound

The artist Santiago X's Serpent Mound in Schiller Woods is the first of two planned effigy mounds along Irving Park Road. Photo: WTTW News

The artist Santiago X's Serpent Mound in Schiller Woods is the first of two planned effigy mounds along Irving Park Road. Photo: WTTW News

The American Indian Center is also involved in another outdoor project honoring the region’s Indigenous people. The Serpent Mound in Schiller Woods is a contemporary effigy mound created by Indigenous artist Santiago X. It’s an earthenwork that draws on a tradition of mound-building amongst Native tribes in the region. (Several ancient mounds have been preserved at Effigy Mounds National Monument in Iowa, just up the Mississippi River from the northwest corner of Illinois.) Serpent Mound is located near the intersection of Irving Park Road and the Des Plaines River, and is part of 4000N, the Northwest Portage Walking Museum, which is meant to celebrate Native and contemporary communities along Irving Park between the Des Plaines and Chicago Rivers. Another effigy mound called Coil Mound is planned for the other end of 4000N, at Horner Park and the Chicago River.

Kwanusila

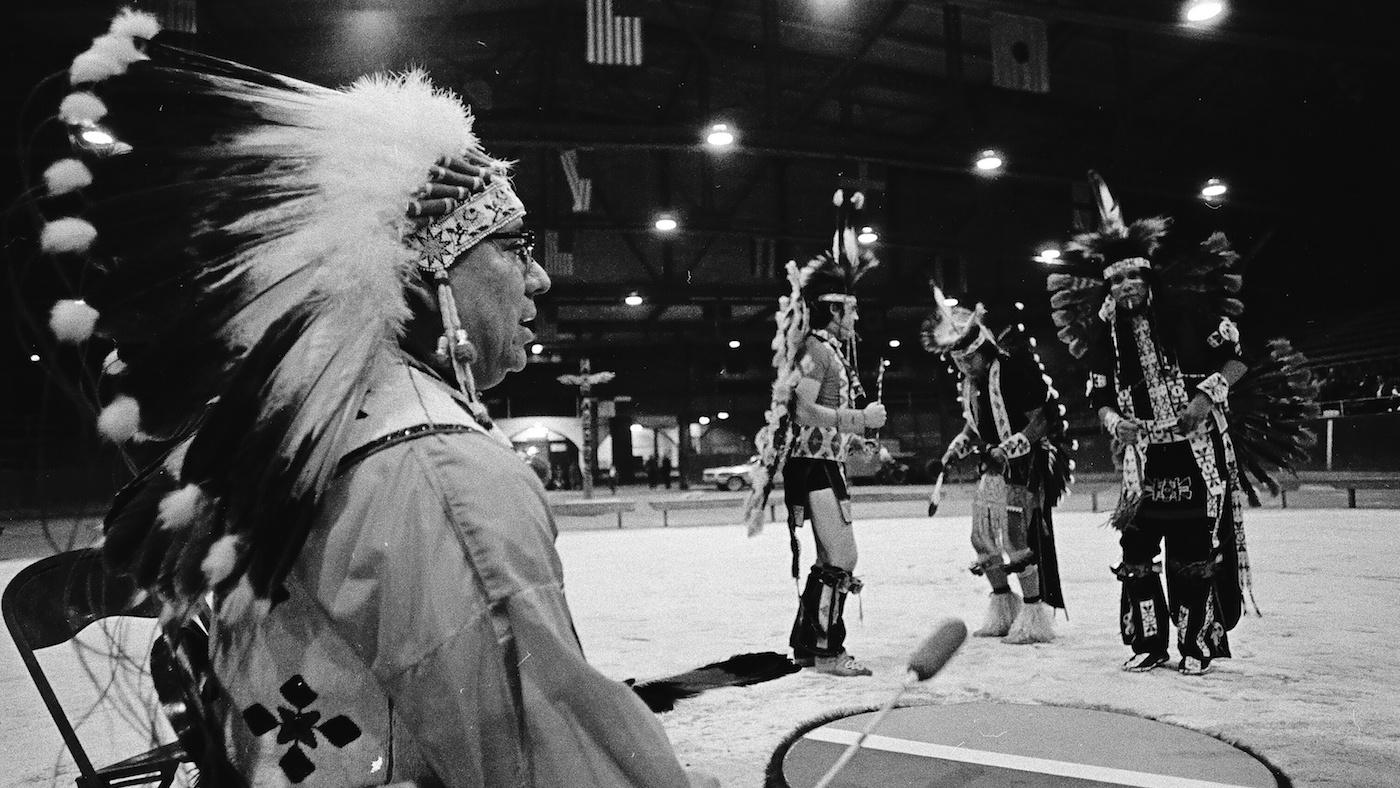

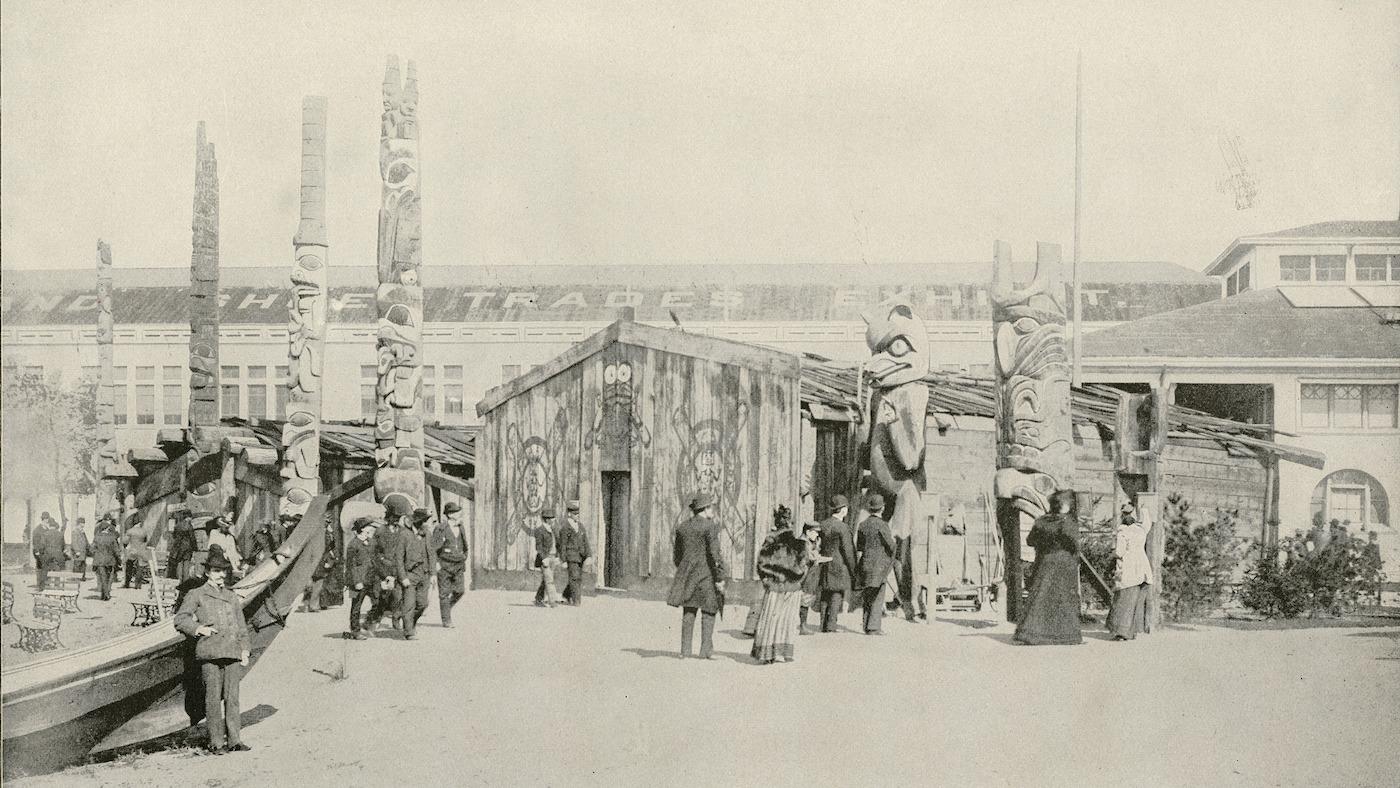

The Kwakiutl tribe at Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-068016

The Kwakiutl tribe at Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-068016

As you pass Addison Street on Jean-Baptiste Point DuSable Lake Shore Drive, you’ll notice a totem pole standing in Lincoln Park. Called Kwanusila, it features a thunderbird gripping the tail of a whale that is itself balanced on a sea monster. According to an article in the late Gapers Block, it was carved by Tony Hunt of the Kwakiutl tribe of British Columbia, and is a replacement of a totem pole donated to Chicago by James L. Kraft, the founder of Kraft Inc., in 1929. After enduring decades of deterioration, the original totem pole was sent to the Museum of Anthropology at the University of British Columbia in 1985 in order to better conserve it. Kraft Inc. then commissioned a new totem pole for the city from Hunt, who is a descendant of George Hunt, a Tlinglit Indian who was raised Kwakiutl and put together an exhibit of Native Americans for Chicago’s 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.

Field Museum

Many of the objects from George Hunt’s exhibit were donated to the fledgling Field Museum, which now holds an extensive collection of Native American artifacts, some collected under problematic circumstances. The Museum is currently undergoing a renovation of its Native North American Hall, which had changed little since the 1950s. The project, in partnership with the American Indian Center and Native American scholars and community members, aims to better represent the history and contemporary lives of Native Americans. It will also include the work of contemporary Native artists such as Chris Pappan, an enrolled member of the Kaw Nation.

Mitchell Museum of the American Indian

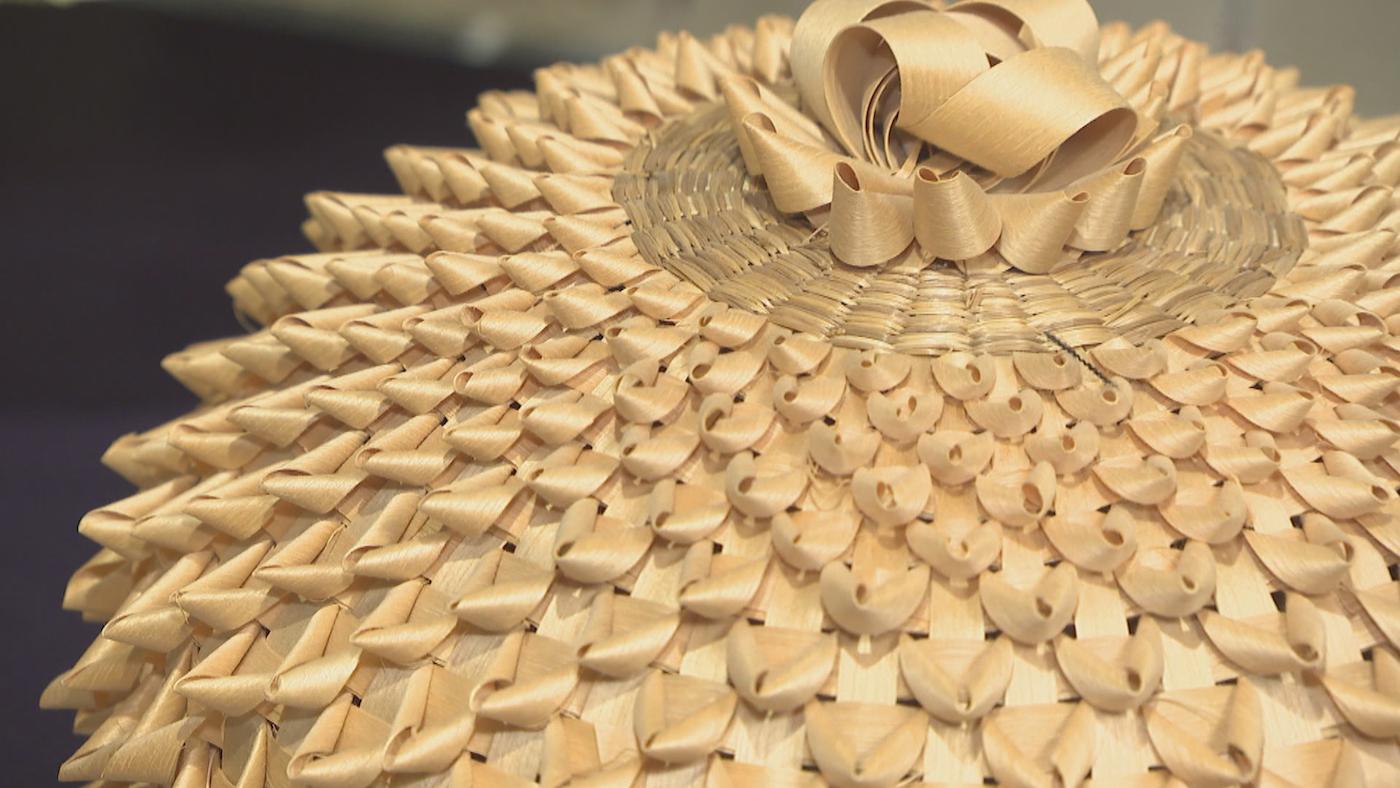

Woven art at the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in a 2018 exhibit. Image: WTTW News

Woven art at the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian in a 2018 exhibit. Image: WTTW News

Another museum that holds a collection of Native artifacts and materials can be found in Evanston: the Mitchell Museum of the American Indian. Founded in 1977 after the private collectors John and Betty Seabury Mitchell donated their personal collection of 3,000 Native American artifacts to Kendall College in Evanston, it has been independent since 2006. It now holds over 10,000 objects, with particular emphasis on textiles, jewelry, and sculpture.