Ten of Chicago's Most Iconic Restaurants, Past and Present

Daniel Hautzinger

June 21, 2022

Iconoclasm is sweeping Chicago as if a pack of zealous Calvinists had taken over. In the past few months, several iconic neon restaurant signs have gone up for sale: Dinkel’s Bakery closed after more than 100 years and put its sign on the auction block; Joe’s Pub and its sign are also no more after four decades; and the “Chop Suey” sign of 90 year-old Chinese restaurant Orange Garden was bought by Smashing Pumpkins front man Billy Corgan’s partner as the restaurant’s owners sell the business.

It seems as good a time as any to celebrate some of Chicago’s most iconic restaurants, shuttered and still extant. By “iconic” we mean well-known, generally long-lasting spots that have a memorable setting and design—the kind of place where the surroundings and ambience are an inextricable and indelible part of the experience. Here are ten.

The Berghoff

Hermann Berghoff opened his original restaurant, seen here in 1911, in order to sell beer in Chicago. Photo: DN-0008950, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

Hermann Berghoff opened his original restaurant, seen here in 1911, in order to sell beer in Chicago. Photo: DN-0008950, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

One of the oldest restaurants in America came out of an entrepreneurial immigrant’s desire to sell beer. Herman Berghoff came to America from Germany and eventually opened a brewery in Fort Wayne, Indiana. He peddled his beer outside the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, having been denied permission to set up inside the fair. Authorities later prevented him from distributing his beer in Chicago, so in 1898 he opened the Berghoff Café in the city to sell it himself.

The Berghoff’s original building was demolished in 1913, so the restaurant moved to its current location at 17 W. Adams. Its large neon sign still draws the eye, while the oak-paneled interior with its murals of the World’s Fair, stained glass windows, and chandeliers matches the restaurant’s Old World German food: schnitzel, spätzle, sausage, strudel.

Herman’s namesake grandson closed the restaurant in 2006 after he turned 70, but it quickly reopened under Herman’s great-granddaughter Carlyn, a caterer, and still exists today—even if beer is now a bit pricier than a nickel and no longer comes with a free corned beef sandwich.

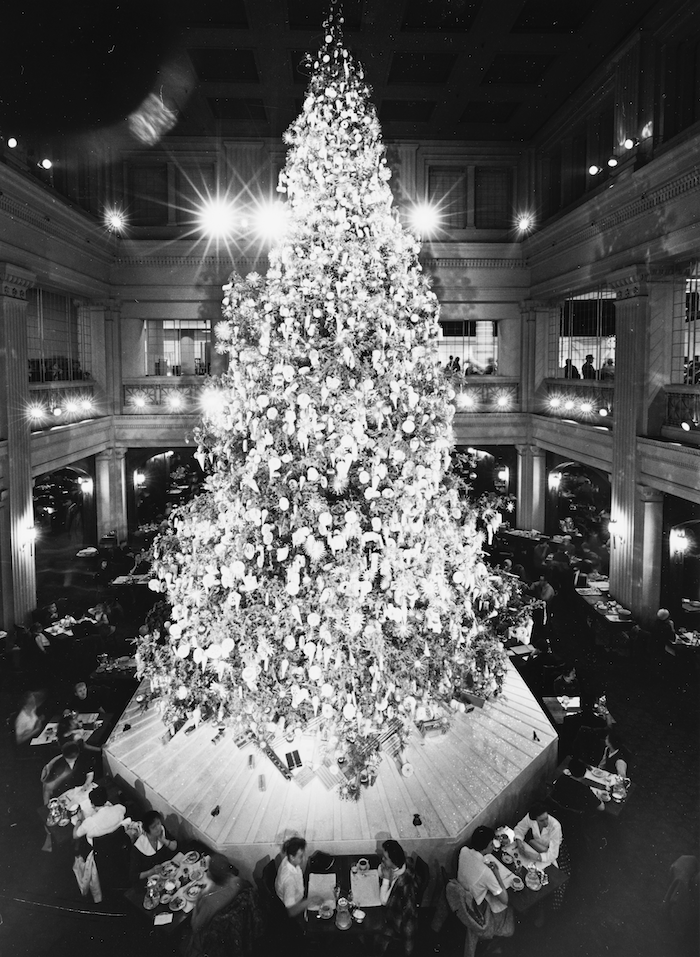

The Walnut Room at Marshall Field’s

The Walnut Room's Christmas tree in 1959. Photo: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-017139; Clarence W. Hines, photographerThere’s another wood-paneled dining room downtown with a long history in Chicago, although not quite as long as the Berghoff. The Walnut Room on the seventh floor of what used to the Marshall Field’s on State Street—now a Macy’s—supposedly traces its roots to the success of a store clerk’s chicken pot pie. The apocryphal origin story is that a Sarah Hering working in the millinery department shared her lunch of chicken pot pie with a customer, and word quickly spread. Store manager Harry Selfridge saw the popularity of Hering’s pies and decided to open a tea room in the store in 1890; eventually it was moved to the 17,000 square-foot dining room still in use today, which became officially known as “The Walnut Room” by 1937.

The Walnut Room's Christmas tree in 1959. Photo: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-017139; Clarence W. Hines, photographerThere’s another wood-paneled dining room downtown with a long history in Chicago, although not quite as long as the Berghoff. The Walnut Room on the seventh floor of what used to the Marshall Field’s on State Street—now a Macy’s—supposedly traces its roots to the success of a store clerk’s chicken pot pie. The apocryphal origin story is that a Sarah Hering working in the millinery department shared her lunch of chicken pot pie with a customer, and word quickly spread. Store manager Harry Selfridge saw the popularity of Hering’s pies and decided to open a tea room in the store in 1890; eventually it was moved to the 17,000 square-foot dining room still in use today, which became officially known as “The Walnut Room” by 1937.

“Mrs. Hering’s” chicken pot pie recipe remains on the menu today, whether Hering existed or not, and generations of Chicagoans have visited the Walnut Room to enjoy the pie or the towering Christmas tree that adorns the Walnut Room at the holidays.

Won Kow

Won Kow's building has changed little since it opened in 1928, the year pictured here. Photo: DN-0085745, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

Won Kow's building has changed little since it opened in 1928, the year pictured here. Photo: DN-0085745, Chicago Sun-Times/Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

Orange Garden on Irving Park Road, which just sold off its sign, became the oldest continuously operating Chinese restaurant in Chicago after Won Kow in Chinatown closed in 2018. Won Kow’s sign is as noticeable as Orange Garden’s, although Won Kow’s building, little changed since it opened in 1928, is more ornate. (The restaurant’s first owners were also important members of the On Leong Chinese Merchants Association that was headquartered across the street in the florid, pagoda-topped building now known as the Pui Tak Center.)

In its later decades, the second-floor restaurant served tiki drinks to tables outfitted with lazy susans, while in earlier days it was open until 2:00 AM and featured mirrored paneling. It was already a stalwart back in 1931, when John Drury noted in his book Dining in Chicago that “The waiters here are very courteous and will show you how to use chopsticks in case you don’t know how to handle them.”

Pump Room

One dish at the Pump Room was served by waiters from flaming swords. Photo: HB-07662, Chicago History Museum, Hedrich-Blessing Collection

One dish at the Pump Room was served by waiters from flaming swords. Photo: HB-07662, Chicago History Museum, Hedrich-Blessing Collection

For decades, the Pump Room hosted celebrities alongside food presented with a drama worthy of the Hollywood stars enjoying it. Opened in 1938 in the Gold Coast’s Ambassador East Hotel, the Pump Room shimmered with chandeliers, live dance music, and stardom seated in leather booths—especially the legendary booth one near the door, where luminaries including Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Elizabeth Taylor, Frank Sinatra, and more could be found.

Waiters dressed in vivid red coats flambéed steak Diane tableside, served roast pheasant adorned with its original feathers, and walked through the restaurant with flaming tidbits of lamb speared on swords. The restaurant went through numerous iterations after the glamour of its heyday passed, but it still exists as the Ambassador Room, now refinished in a modern style.

Superdawg

Twelve-foot tall hot dogs on the roof, carhops serving you at a drive-in: Superdawg is unlike anywhere else left in the city. Photo: Eric Allix Rogers/Flickr

Twelve-foot tall hot dogs on the roof, carhops serving you at a drive-in: Superdawg is unlike anywhere else left in the city. Photo: Eric Allix Rogers/Flickr

You might think eating in your car can’t be memorable unless you spill a sticky beverage all over your upholstery, but this far Northwest Side hot dog stand proves you wrong. The last remaining drive-in restaurant within Chicago, Superdawg lets you park under a canopy, order through a speaker, and receive your food from a carhop without ever leaving your vehicle.

And that’s not the only memorable thing about the restaurant, which was opened in 1948 by the recently married Maurie and Flaurie Berman. The retro, minimal building—designed by Maurie, according to the restaurant—is topped by a pair of twelve-foot hot dog people, one outfitted in a skirt and bow and the other in a leopard pelt. Maurie and Flaurie have passed, but the business is still run by their family. One additional location that mimics the design of the original exists in the northwest suburb of Wheeling.

Lem’s Bar-B-Q

Lem's Bar-B-Q's towering exhaust pipe—and the tantalizing scent of smoke—announce the barbeque institution's presence on 75th Street. Photo: Wikimedia/Amy C. Evans of Southern Foodways Alliance

Lem's Bar-B-Q's towering exhaust pipe—and the tantalizing scent of smoke—announce the barbeque institution's presence on 75th Street. Photo: Wikimedia/Amy C. Evans of Southern Foodways Alliance

The Chicago Reader called this South Side institution “a civic treasure,” and it continues to draw crowds to 75th Street for its hot links and rib tips made in a unique-to-Chicago aquarium smoker. Brothers Myles and Bruce Lemons came to Chicago from Indianola, Mississippi and then opened the first Lem’s in 1954, adapting their mother Anna’s tangy sauce for their ribs. Another brother, James, opened the current and only remaining location in 1968. James died in 2015, but his daughters continue to run the place. Aretha Franklin, Denzel Washington, Scottie Pippen, and others have all enjoyed the smoke shack, according to the Chicago Crusader.

A former ice cream and milkshake parlor, the bare bones eatery with its towering exhaust pipe still features a drink with a straw in its flashy green and orange sign. The best place to dig into the sauce-soaked ribs with their accompanying piece of white bread is in the parking lot, where you can enjoy the smoky scent emanating from the building.

Maxim's de Paris

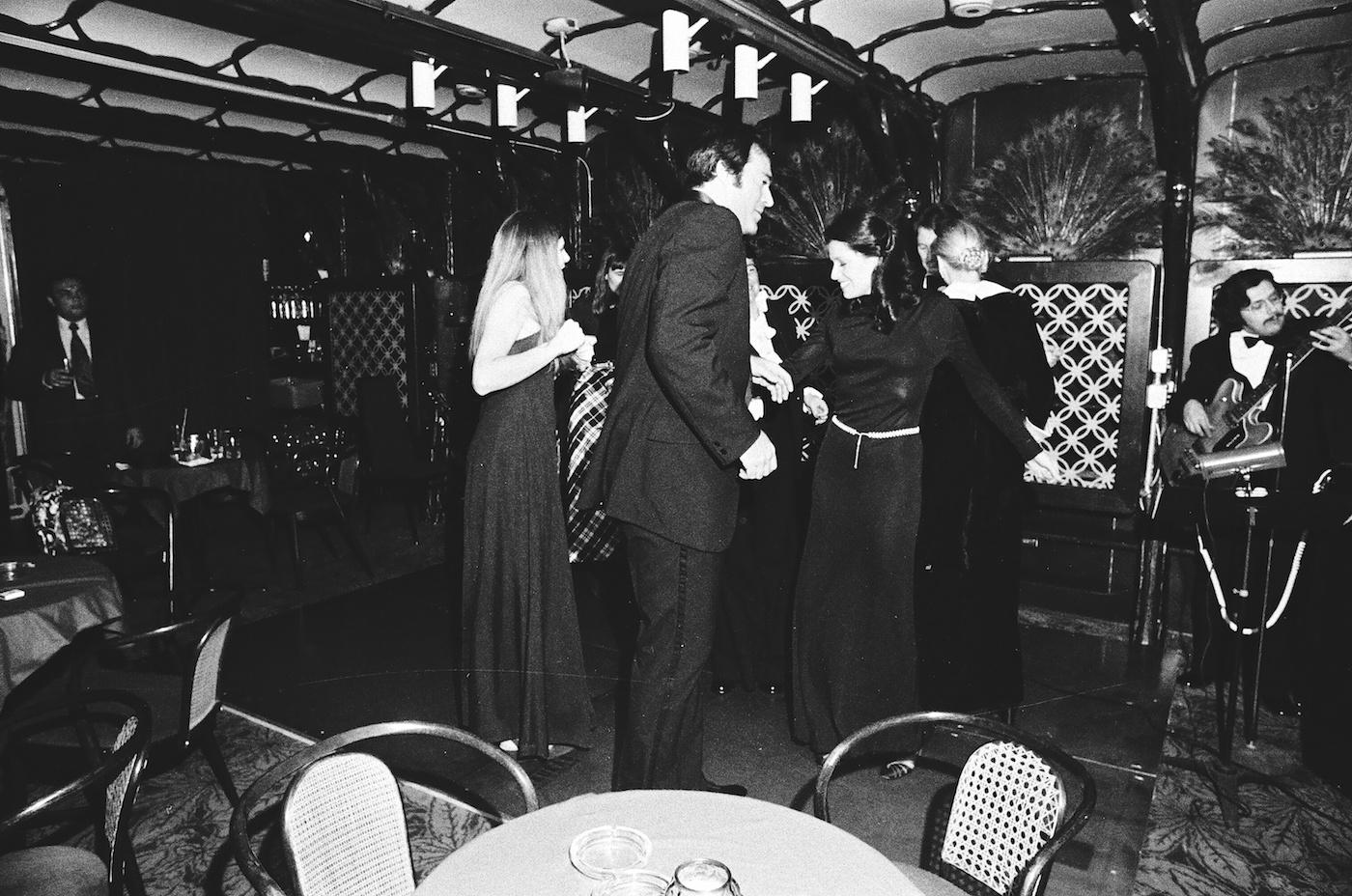

Maxim's contained Chicago's first discotheque, seen here in 1972, and also helped introduce haute cuisine and some important French chefs to the city. Photo: ST-13002498-0020, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

Maxim's contained Chicago's first discotheque, seen here in 1972, and also helped introduce haute cuisine and some important French chefs to the city. Photo: ST-13002498-0020, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

Even though it was inspired by a famous Art Nouveau restaurant in Paris, Chicago’s Maxim’s de Paris was actually designed by a modernist architect. Bertrand Goldberg, the architect behind Marina City, designed the striking Astor Tower in the Gold Coast and needed a restaurant for its basement. His wife, Nancy Goldberg, and her mother, the artist and art collector Lillian Florsheim, suggested modeling it on the legendary French Maxim’s de Paris, as Block Club Chicago recounted.

Bertrand helped design much of the flatware and plateware in addition to the interior, while Nancy stepped in to operate the restaurant, which opened in December of 1963. It helped introduce French wines and haute cuisine to Chicago, with talented French chefs brought here by Nancy to work in Maxim’s. Like the Pump Room, it was a notable spot for celebrities and also contained the city’s first discotheque.

It closed in 1983 and went through several failed iterations in the decades since. Now it is being turned into a private club for residents of its Gold Coast neighborhood.

Everest

One of the French chefs whose career was launched at Maxim’s de Paris was Jean Joho. In 1986, he went on to open Everest with the Lettuce Entertain You restaurant group. It had one of the most stunning views of any restaurant in the city, given that it was located on the 40th floor of the Chicago Stock Exchange.

Not that you would know it was there. It didn’t have a sign, and guests took three elevators from the parking garage to the restaurant. It achieved lofty heights, racking up numerous awards for the Alsatian cuisine with locally sourced ingredients—Everest was one of the first Chicago restaurants to offer a tasting menu. It closed at the end of 2020.

Blackbird

Blackbird's minimalist design won a James Beard Award, while its innovative food won over Chicagoans. Photo: Doug FogelsonWhen Blackbird opened in 1997, it was out of place. One of of the early innovative restaurants to open in what is now the culinary mecca of the West Loop, its minimalist, heavy-on-white aesthetic distinguished it from other ambitious fine-dining restaurants in Chicago. Led by chef Paul Kahan and Donnie Madia along with two other partners, it became one of the most beloved and acclaimed restaurants in Chicago before falling victim to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Blackbird's minimalist design won a James Beard Award, while its innovative food won over Chicagoans. Photo: Doug FogelsonWhen Blackbird opened in 1997, it was out of place. One of of the early innovative restaurants to open in what is now the culinary mecca of the West Loop, its minimalist, heavy-on-white aesthetic distinguished it from other ambitious fine-dining restaurants in Chicago. Led by chef Paul Kahan and Donnie Madia along with two other partners, it became one of the most beloved and acclaimed restaurants in Chicago before falling victim to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020.

Its design, by architect Thomas Schlesser, won a James Beard Award. Its seasonal but inventive food wowed guests, and was often more affordable than similar restaurants. It launched the careers of numerous other Chicago chefs, and was the foundation of Kahan and Madia’s One Off Hospitality group, which includes the next-door Avec, Big Star, the Publican, and more. Those still exist, but Blackbird, the original, remains an icon—and an early harbinger of Chicago’s creative food renaissance of the past two decades.

Cherry Circle Room

The Cherry Circle Room in the Chicago Athletic Association building is a reimagined version of a private club's restaurant. Photo: Clayton Hauck

The Cherry Circle Room in the Chicago Athletic Association building is a reimagined version of a private club's restaurant. Photo: Clayton Hauck

Once again, we have a downtown dining room that prominently features fine wood—but this time the restaurant is relatively new, sort of. The Cherry Circle Room is located in the Chicago Athletic Association building, an ornate edifice modeled on the Doge’s Palace in Venice that opened on Michigan Avenue in 1893, during the World’s Fair. The whole building served as the home of a private club until 2007, when it closed.

After restoration, the building reopened in 2015 as a hotel and included a newly imagined Cherry Circle Room, which had served as a restaurant. Land and Sea Dept., which won a James Beard Award for their design of the space, kept the original cherry wood walls, curved bar, and other features. The menu references historical dishes and cocktails; an eight-seat speakeasy-style bar showcases rare and vintage spirits. Walking through the two lobbies of the Chicago Athletic Association building as well as its game room to get to the Cherry Circle Room is an integral part of the experience.