Revisiting Some of Chicago's Lost Amusement Parks

Geoffrey Baer

August 25, 2022

Do you have fond childhood memories of amusement parks? My father always spoke of Riverview like it was nirvana. He would spin tales of his youth there: exploring the funhouse named Aladdin’s Castle, sitting in the front row of Shoot the Chutes with his brother and ducking just before their car hit the water so that the passengers behind them got soaked. The park at Western and Belmont Avenues thrilled kids of all ages from 1904 until it abruptly closed after the 1967 season.

I visited Riverview once as a young child in the years before it closed, but the amusement park I remember better is the Kiddieland in Skokie. I loved riding the miniature train called the Hiawatha as well as a small roller coaster—the Wild Mouse roller coaster was a bit too scary for me!

Of course, neither Riverview nor any Kiddieland survives, although Gurnee’s Great America, which opened in 1976 and was sold to Six Flags in 1984, still delights visitors today. Here’s a look back at some of the other amusement parks that have exhilarated generations of Chicagoans.

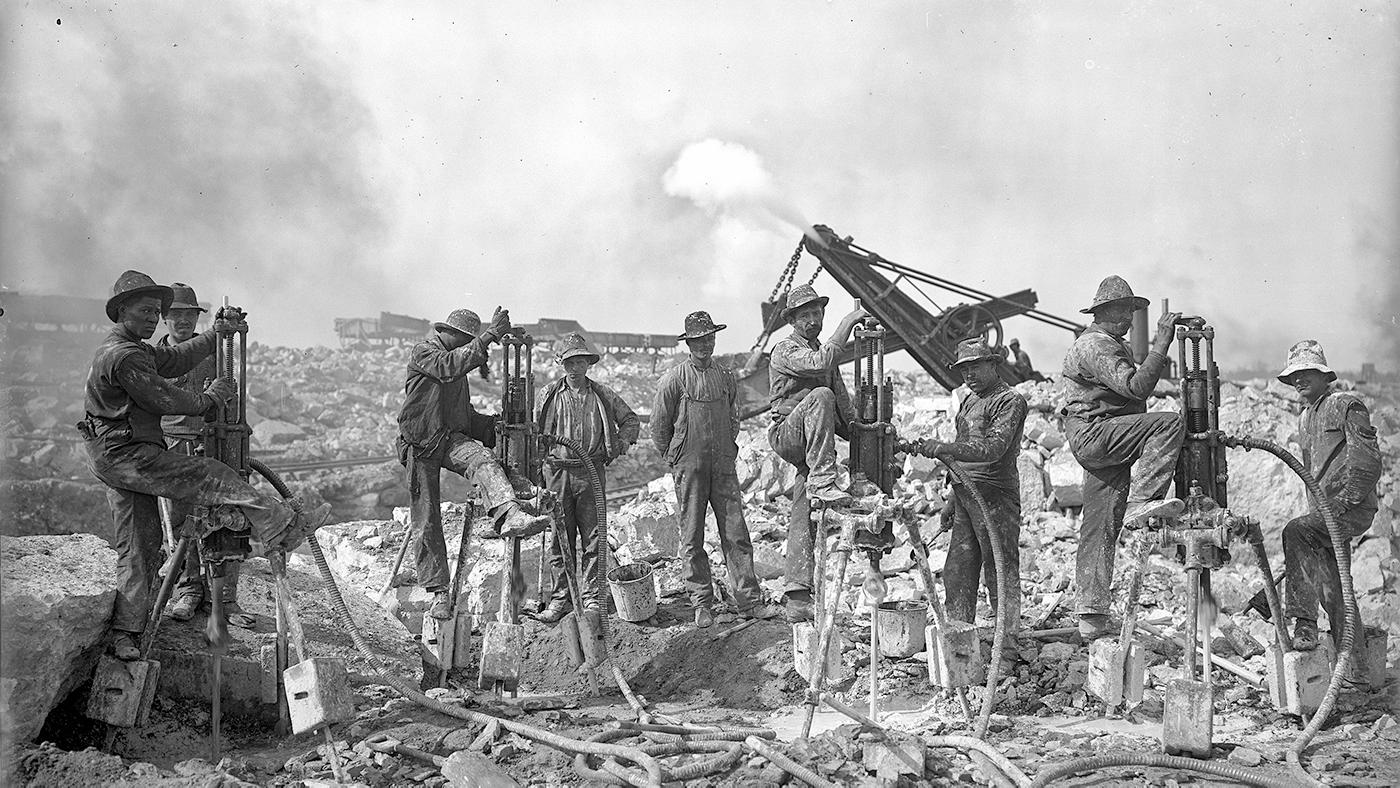

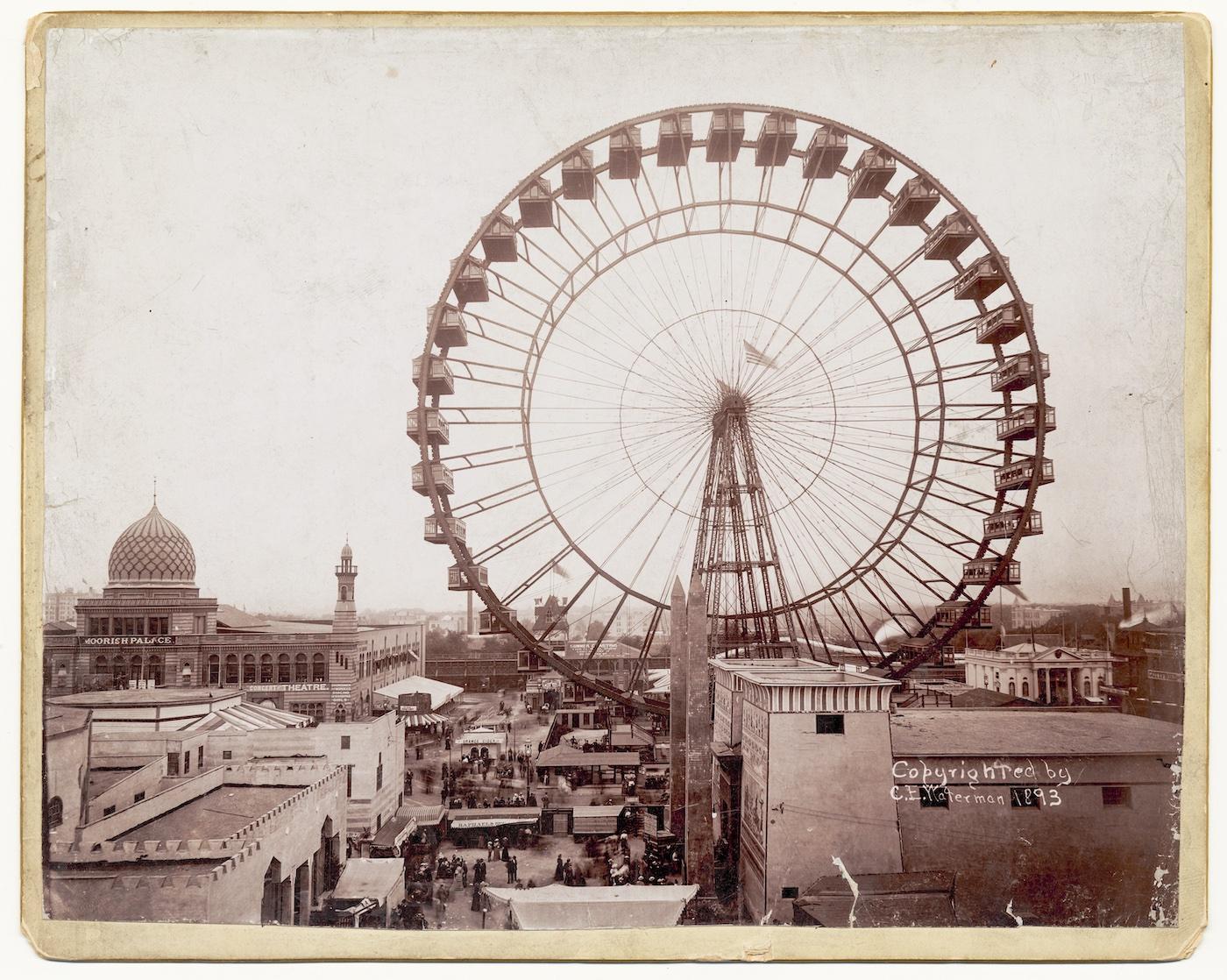

The Midway at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893

The Midway at the World's Columbian Exposition paired rides such as the world's first steel Ferris wheel with displays of culture such as the Moorish Palace. Photo: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-002440; C. E. Waterman, photographer

The Midway at the World's Columbian Exposition paired rides such as the world's first steel Ferris wheel with displays of culture such as the Moorish Palace. Photo: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-002440; C. E. Waterman, photographer

It all starts with the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 and its bustling Midway, which housed attractions such as the world’s first steel Ferris Wheel alongside concessions, games, and sideshow displays of cultures around the world. (Not that the depictions were ennobling, accurate, or respectful: for instance, a pair of sisters from Romania performed as “Arabs” in the Moorish Palace.)

The popularity of the Midway inspired entrepreneurs around the country and in Chicago to try to replicate its success—sideshow and concessions areas at fairs and carnivals today are called “midways” after the original at the world’s fair. As for the Ferris Wheel, it was moved to Lincoln Park, where it starred in one of the first films in the world. (It’s one of my favorite instances of Chicago on film.) It then showed up at the 1904 St. Louis world’s fair before being dynamited and sold for scrap. In 1995, Navy Pier added a Ferris Wheel in honor of that first one. At approximately 15 stories tall, it was half the size of the original; it was replaced for the Pier’s centennial in 2016.

Paul Boyton’s Water Chute

Less than a year after the World’s Columbian Exposition closed, its Midway already had an imitator: Paul Boyton’s Water Chute, which opened on July 4, 1894 at 63rd Street and Drexel Avenue, just south of the Midway. It was America’s first modern amusement park, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago. Whereas earlier recreational parks or pleasure gardens relied on natural features to attract visitors, Boyton introduced a Shoot the Chute water ride in an attempt to replicate the success of the Ferris Wheel. A showman and aquatic stuntman, Boyton opened a park on Coney Island the next year.

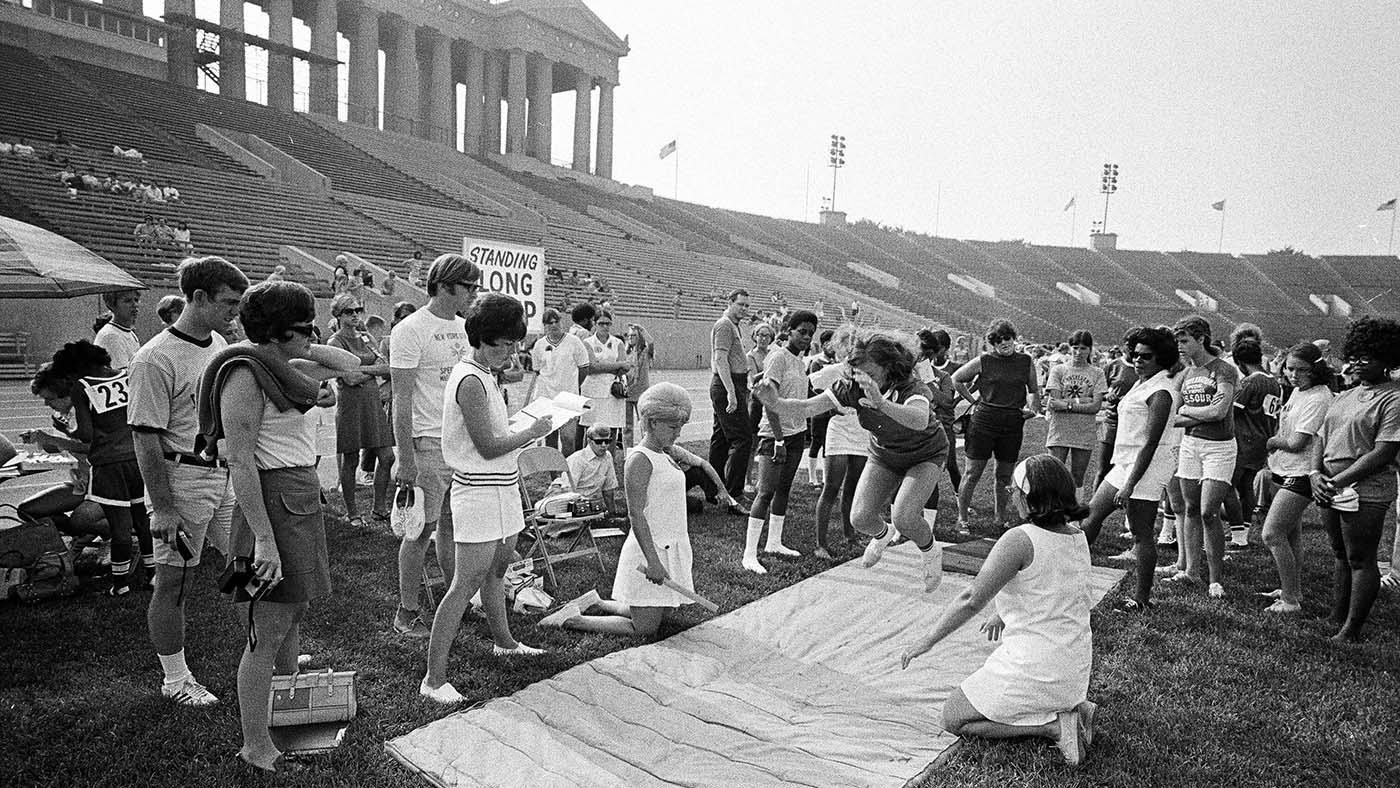

Sans Souci

Sans Souci was replaced by a short-lived Frank Lloyd Wright project. Photo: DN-0006357, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

Sans Souci was replaced by a short-lived Frank Lloyd Wright project. Photo: DN-0006357, Chicago Daily News collection, Chicago History Museum

Chicago had more amusement parks than anywhere else in the country until 1908, according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, and that’s evident in the explosion of new ones that opened around the turn of the century. Many were short-lived, including Luna Park, which lasted from just 1907 to 1911 on the South Side. Sans Souci was bigger and existed for just a little longer, but its abortive afterlife is fascinating.

Sans Souci was located just off the Midway Plaisance, which had hosted the 1893 Midway. Impressed by the traffic going to a beer garden, streetcar operators bought the land in 1899 and expanded it into a park with entertainments such as gardens, fountains, and live music, according to the website Jazz Age Chicago. More lively attractions such as roller coasters and a skating rink were added in response to competition from White City (see below), but the park still failed to survive.

In 1914, Frank Lloyd Wright remodeled it into Midway Gardens, an outdoor performance space and restaurant where you could watch ballet or listen to a symphony. (Up on the North Shore, Ravinia similarly started off as a pleasure ground that also featured music.) Wright participated in every aspect of the design, even the dishware and murals. (You can see more images of Midway Gardens in my Chicago’s South Side, starting at 20:45.) When the venture was bought two years in by a brewery, Wright was outraged by the company’s alterations. Prohibition put an end to it, and it was demolished in 1929 after stints as a car wash, among other things.

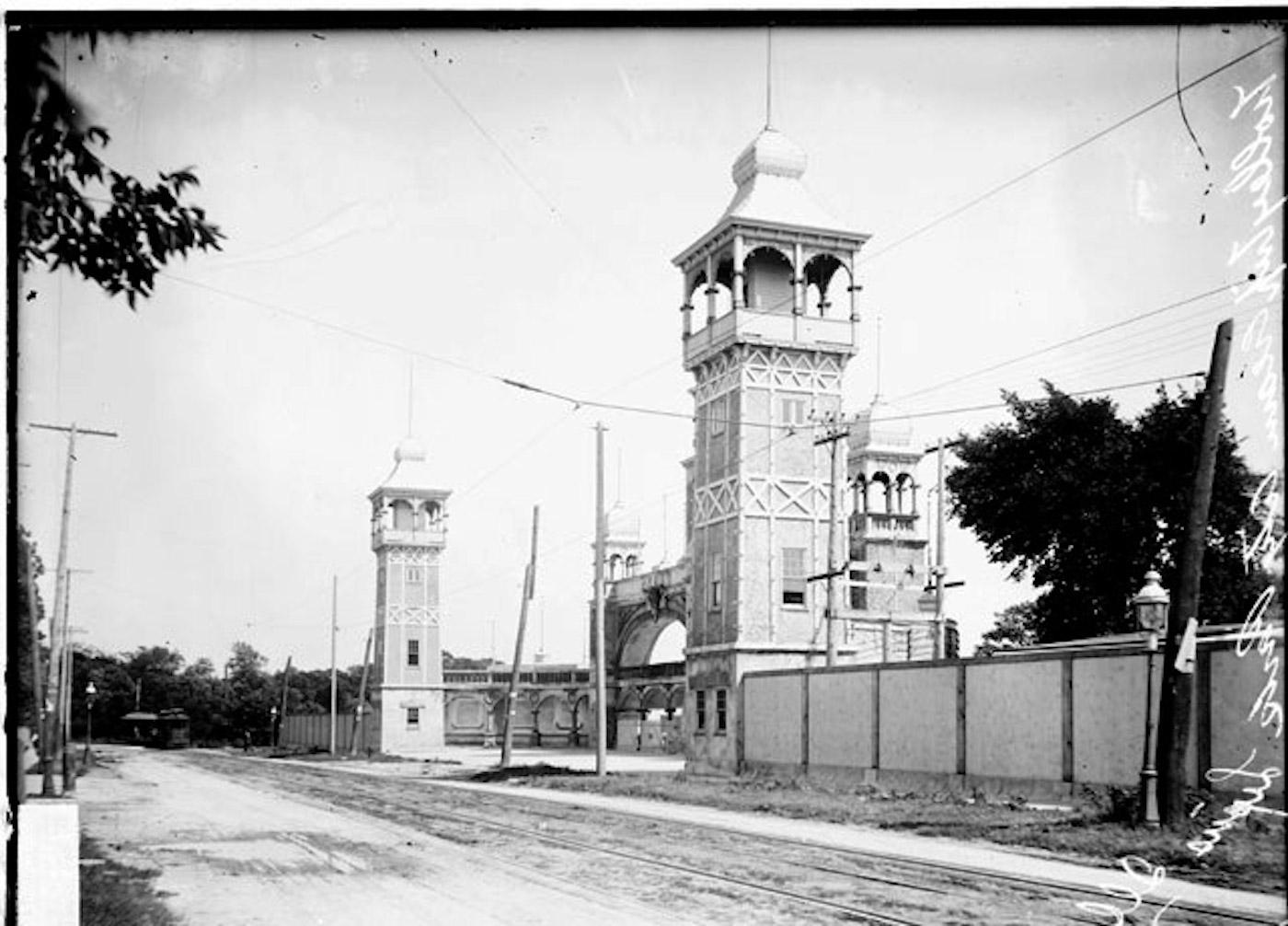

Riverview Park

William Schmidt, the owner of Riverview, looks out over the park in 1967. ST-90004580-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

William Schmidt, the owner of Riverview, looks out over the park in 1967. ST-90004580-0003, Chicago Sun-Times collection, Chicago History Museum

The park my father adored is perhaps the best-known in the Chicago area—WTTW even has a whole documentary about it that you can stream. It had such famed rides as the Bobs roller coaster and a tunnel of love, as well as a dark side: sideshows that made spectacles of disabled people or debased African Americans. We’ll let you watch the documentary for much more detail.

White City

White City's "Electric Tower" was 300 feet tall and had 20,000 lightbulbs. Photo: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-070022; Charles R. Clark, photographer

White City's "Electric Tower" was 300 feet tall and had 20,000 lightbulbs. Photo: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-070022; Charles R. Clark, photographer

Sans Souci’s demise was due in part to the opening of White City nearby, on property that is now Parkway Gardens, where Michelle Obama spent her early life. Opened in 1905, it was a larger park with more rides and attractions, including its famous “Electric Tower,” whose 300 feet of height was illuminated by 20,000 lightbulbs. (You can see footage of White City in my Chicago’s South Side, starting at 20:57.)

While the name was a reference to the white buildings of the World’s Columbian Exposition, it may as well have referred to the clientele: shamefully, Blacks weren’t allowed. It began shuttering attractions during the Great Depression, and by the latter half of the 1930s it had been reduced to just a dance hall, roller rink, and some sports areas before closing completely, according to Jazz Age Chicago.

Cream City

This amusement park, opened in 1906 in the western suburb of Lyons, is possibly the shortest-lived in the Chicago area: it burned down after only one year, according to the Village of Lyons Historical Commission. (The nearby suburb of Forest Park was also home to an amusement park in the early twentieth century.) But Lyons continued to be known as a place for fun—and debauchery. One commentator called it “bibulous…the chosen abode of Bacchus and Terpsichore,” according to the Encyclopedia of Chicago—aka heavy drinking, and fond of parties and dancing. A 1908 vote to abolish saloons was trounced (244 to 14), while an eight-story tower built by local brewer George Hofmann that same year became the centerpiece of a recreational area that included a beer garden and other entertainments. Hofmann Tower still stands today.

One additional attraction hosted by Lyons? A “Whoopee Coaster” built in the late 1920s that allowed visitors to drive their own car along the hilly, winding wooden track, at a maximum speed of five miles per hour.

You can see more about Lyons’ history as a party town in my Chicago’s Western Suburbs beginning at 9:30.

Max speed on the Whoopee Coaster? Five miles an hour. Image: From 'Chicago's Western Suburbs'

Max speed on the Whoopee Coaster? Five miles an hour. Image: From 'Chicago's Western Suburbs'

Joyland Park

Unlike White City, Joyland Park in Bronzeville not only welcomed Black Chicagoans—it was owned and operated by them. Much smaller than Riverview or White City, at only two acres, it had four rides, according to the website Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal. It only lasted from 1923 to 1925, and the land it occupied is now part of the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Kiddieland

The Kiddieland sign now stands outside the Melrose Park Library. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/S Jones

The Kiddieland sign now stands outside the Melrose Park Library. Photo: Wikimedia Commons/S Jones

During the Depression, Arthur Fritz bought ponies to sell rides to children in the western suburbs after he lost his job as a contractor. He eventually established the first Kiddieland in Melrose Park by adding miniature cars, according to Melrose Park’s website. He failed to trademark the name, leading to copycats across the area, including the one I enjoyed as a child in Skokie. (The family that bought and improved Novelty Golf in Lincolnwood also owned a Kiddieland at Devon Avenue and McCormick Boulevard.) Only the original Kiddieland survived into the 2000s, but even it was demolished in 2010—although its colorful sign was preserved and now sits outside the Melrose Park Library.

You can see footage of Kiddieland in my Chicago’s Western Suburbs beginning at 1:19:29.

Santa’s Village

Believe it or not, the idea of a Christmas-themed amusement park originated in California. Entrepreneur Glenn Holland opened two Santa’s Villages in California in the 1950s (the first predated Disneyland’s opening by six weeks, according to the Santa’s Village website). He then decided to expand to the Midwest and place a Santa’s Village in East Dundee in 1959, but never opened any more parks after that.

A giant Christmas tree, puppet shows, a reindeer barn, and a gingerbread house were among the entertainments. At one point the Chicago Blackhawks practiced and played exhibition games in the Village’s Polar Dome Ice Arena, according to the park’s website. The park closed in 2005, but was then reopened in 2010, making it the only surviving Santa’s Village in the country—and the only extant amusement park on this list!

Old Chicago

Did you know the Chicago area was home to a precursor to the Mall of America? Back in 1975, a mall that contained amusement park rides, a concert venue, and circus performers opened in the southwestern suburb of Bolingbrook. Old Chicago only lasted until 1980, facing competition from Great America as well as a lack of big anchor stores to draw people to its then-remote location. It was demolished in 1986—Amazon bought the site in 2020—but the idea behind it was taken up in the Mall of America, which opened in Minnesota in 1992.