Food as a Teaching Tool: How One CPS Teacher Used Food to Connect with Her Students

Meredith Francis

September 21, 2022

During the height of the pandemic and remote learning in schools, Chicago Public School teacher Brenda Armstrong was supposed to use her lunchtime as "her time." But she sometimes spent that time instead talking with her eager students about what they were eating.

“We’d sometimes be on camera, and the students would be like, ‘Looking what I'm eating, Mrs. Armstrong!’”

Armstrong was recently a fellow with Pilot Light, a Chicago-based nonprofit that partners with schools to bring food education into the classroom. What that entails varies widely from school to school, according to Pilot Light Executive Director Alexandra DeSorbo-Quinn.

“In some schools you go in and they have a teacher devoted to maybe sustainability or food. But in other schools, they don’t,” DeSorbo-Quinn explains. “It really begs the question, for something so important that we do multiple times a day—we're humans; we eat—why aren't we learning about it in school on a regular basis?”

As part of Pilot Light’s programs, chefs, farmers, and other culinary experts sometimes visit a classroom to do a demonstration or a lesson. But DeSorbo-Quinn says food education is about more than just cooking or nutrition. Pilot Light’s goal is to make food a reliable teaching tool for teachers like Armstrong.

“We're doing more than [teaching nutrition]. We're also covering all these other aspects of food and how it relates to our lives, from the environment to connections with cultures and histories and identities,” DeSorbo-Quinn says. “There's just so much about food that reflects who we are as humans, and the choices that we make connect to our food system as a whole.”

Armstrong became a Food Education Fellow with Pilot Light in 2020. Her mother and grandmother were both teachers, but Armstrong never planned to follow them into the profession. Nevertheless, after 29 years, she still loves it. She’s currently working as an interventionist at Parker Community Academy in Englewood, but was a teacher at Oglesby Elementary School in Auburn Gresham for the previous nine years. It was at Ogelsby that she spent her year as a Pilot Light fellow.

Pilot Light teachers operate on a set of standards that touch on a variety of concepts—such as health, history, and environment—that highlight how malleable food is as a teaching tool.

Armstrong says that in some of the communities she has taught in, there are no nearby or affordable grocery stores.

“They finally got Whole Foods and now they’ve backed out of that neighborhood,” she says. “Even when I would just casually talk to my students about where they got food, they’d say, ‘Oh, the gas station.’”

That has informed some of Armstrong’s lessons. As grocery store shortages were rampant during the pandemic, Armstrong took the opportunity to teach kids about farming, where food comes from, and how it’s produced.

“We were able to talk about farming, we were able to relate it back to [labor activist] Cesar Chavez,” Armstrong says.

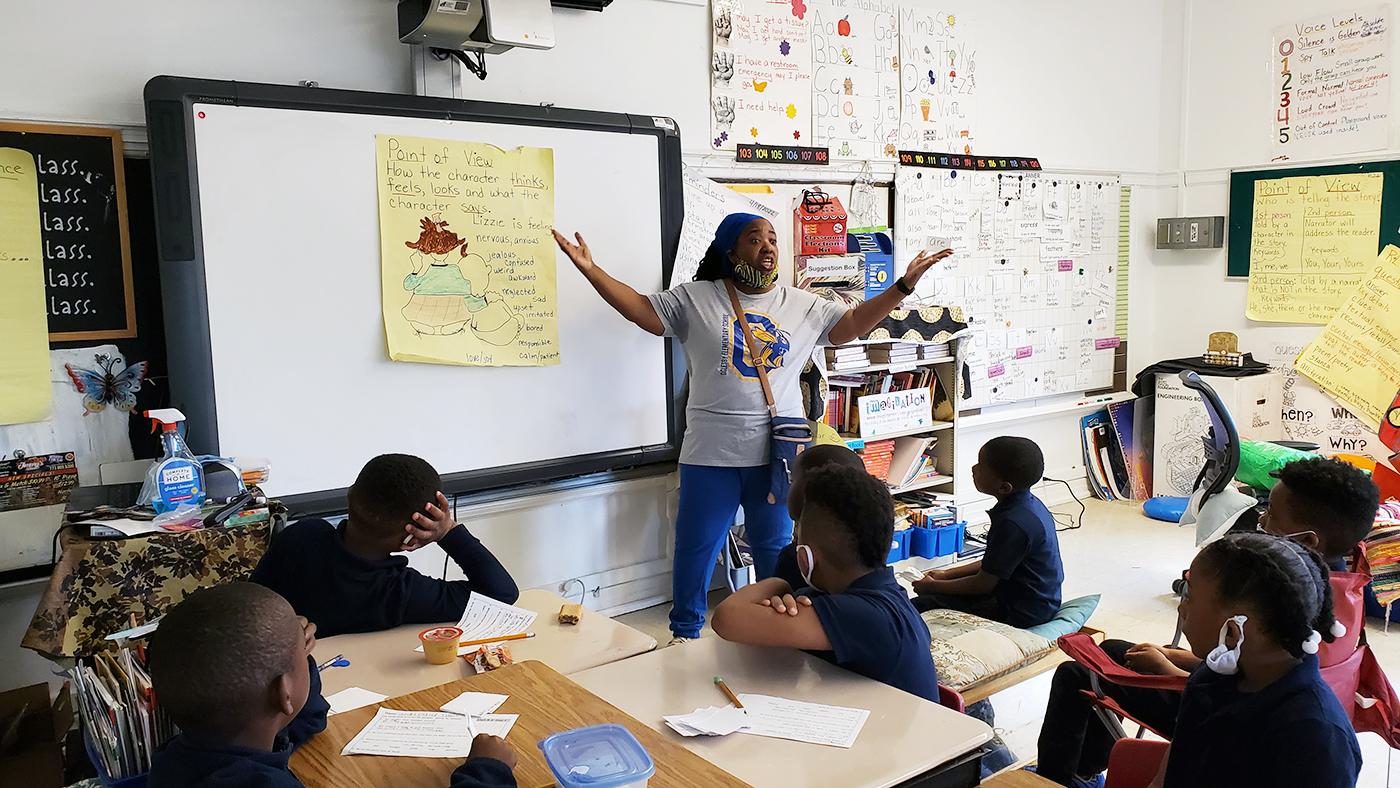

Brenda Armstrong has been a CPS teacher for 29 years. Image: Provided.

Brenda Armstrong has been a CPS teacher for 29 years. Image: Provided.

One of Armstrong’s favorite Pilot Light lessons came while remote teaching during the earlier days of the COVID-19 pandemic with her third graders. It began with a simple “All About Me” exercise, in which she asked students to share facts about themselves using granola mix. Students had to add ingredients that described them in some way.

“So I put some salted peanuts or something in mine. I said, ‘Because I'm kind of sassy and salty,’” Armstrong recalled demonstrating for her students. “Then I put hickory smoked almonds, and I said, ‘I'm a strong person.’ Then I added dried pineapple, ‘because I’m also very sweet.’”

Her students followed suit, allowing them to practice vocabulary and descriptive adjectives. But the food-related learning didn’t stop there. The students then read Freedom on the Menu, a book about the lunch counter civil rights protests in Greensboro, North Carolina. This gave Armstrong the chance to incorporate social studies into the lesson as well as higher-order thinking, such as, “What would you have wanted to order at that lunch counter? How would you have responded?”

“There are so many layers,” Armstrong says. “You can just keep going.”

Similarly, DeSorbo-Quinn points to a fifth grade poetry lesson in another school in which students took inspiration from family recipes as well as fruits and vegetables that were brought into the classroom. The resulting poems were “just so beautiful and personal and really spoke to who these students were and their cultural and ethnic backgrounds,” DeSorbo-Quinn says.

As in those lunchtime interruptions where kids would show off their snacks, food is a topic that often naturally came up in Armstrong’s classroom. A bag of chips, Armstrong says, can be a quick lesson in math—how many calories per serving?

Although remote learning presented all sorts of new challenges, having food be a consistent topic in her classroom actually made for “a much better year.”

“I’m usually very critical of myself, but it was a much better year in terms of social-emotional learning and engaging and connecting with my students and parents than I thought it would be,” she says. “I attribute a lot of that to Pilot Light.”

Those students are now fifth graders, but they still send messages to Armstrong.

“‘Remember how we made cookies? Remember that time you didn’t know how to make mushroom soup?’” Armstrong says, describing the messages. “Even my husband got involved. It really was a great connection for myself and my students.”

That connection is what Armstrong found so useful. Much of the time, she says, she’s a very busy teacher, and it’s hard to find time to stop and really listen to her students or engage with them if they walk up and start a conversation. But when food came up, it was a different story.

“I actually would stop and listen to the conversations about food and the relationships that they had with their families around food. I feel that I gained a lot from it too, just taking the time to listen to them.”

Armstrong describes food as “unifying,” something that levels the playing field and removes the usual teacher-student hierarchy that’s present in the classroom. Just like a shared meal brings people together, food can bring students and teachers together.

“I'm a human being and we both have to live. We have to eat. It’s one of the basic needs that we have. I can also be more vulnerable and they can be vulnerable,” Armstrong says. “You can have a conversation and relationship-building and they can see that you are interested in what they think, which can lead them to being more creative with higher-order thinking.”