Get in the Spirit with Vintage Holiday Cards from the Chicago History Museum

Daniel Hautzinger

December 21, 2022

It’s that time of year, for mailboxes bursting with unwanted catalogs and more welcome holiday cards. Fridges, mantels, and baskets are filling up with photos of friends and family near and far, well-known and barely familiar, along with what we’re sure are some adorable pictures of pets—maybe even some wearing sweaters.

“Anthropomorphizing your animals—not a new tradition,” says Julie Wroblewski of the Chicago History Museum with a laugh. “Thinking about animals and pets as an extension of your family is also something that’s been around for a while, in different ways.”

“Anthropomorphizing your animals—not a new tradition,” says Julie Wroblewski of the Chicago History Museum. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-089189

“Anthropomorphizing your animals—not a new tradition,” says Julie Wroblewski of the Chicago History Museum. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-089189

Take one of the Christmas cards in the archives of the History Museum, where Wroblewski is the Director of Collections. Decades old, the card depicts two dogs in sweaters, one proffering a bone as a gift to the other. It’s Wroblewski’s favorite out of the 68 boxes and fifteen to twenty linear feet of greeting cards from the nineteenth century through roughly the 1960s that are in the museum’s collections. “Something about the framing of it makes me think of the kind of thing that would be a cute animal picture on Instagram or social media these days,” she says.

We’re not so different from people of the past as we might think.

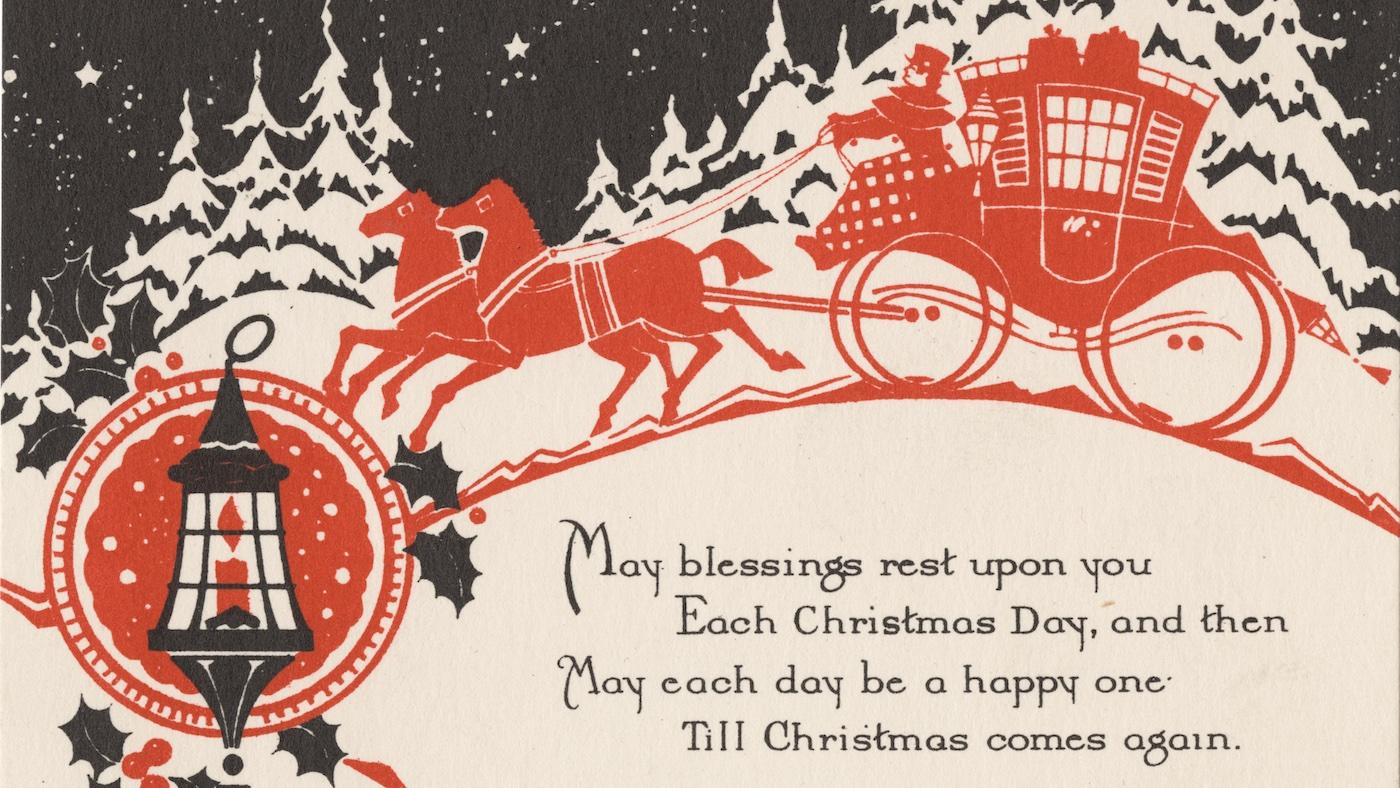

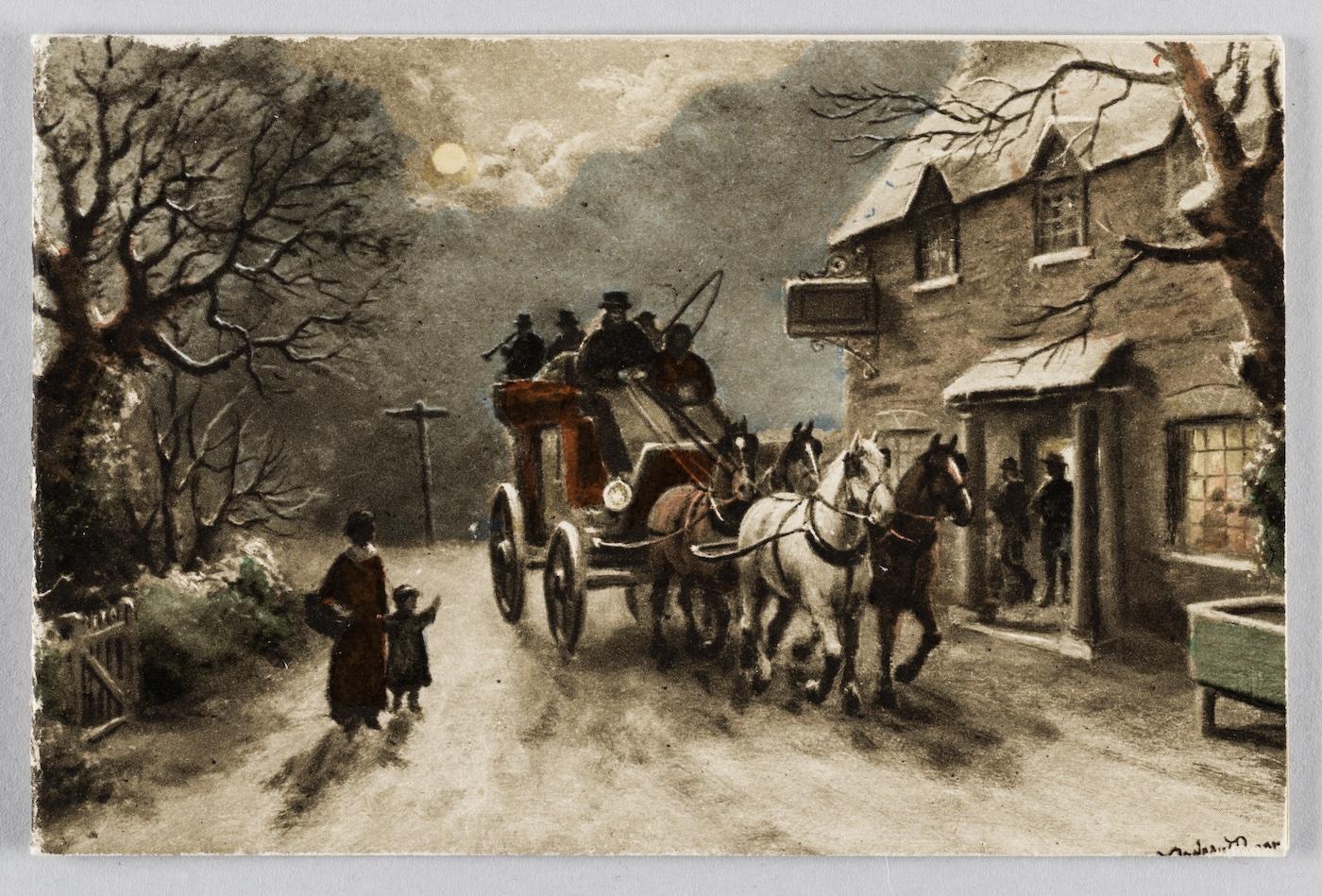

Earlier Christmas cards tend to feature ornate "Dickensian Christmas" scenes. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-085080

Earlier Christmas cards tend to feature ornate "Dickensian Christmas" scenes. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-085080

“Some things never really change,” says Wroblewski. “The invention of the greeting card, specifically of Christmas or end-of-year cards, came from people looking to reduce the amount of individualized, personalized letter-writing that they were doing.”

The creation of the Christmas card is attributed to Sir Henry Cole, a British civil servant involved in London’s Crystal Palace Exhibition and the beginnings of the Victoria and Albert Museum. As Wroblewski puts it, he “was sort of bemoaning, ‘I have too many friends! I can’t write letters to all of these people!’” In 1843, he commissioned an artist acquaintance, J.C. Horsley, to illustrate holiday scenes on a postcard with a generic greeting that he could then send to all of the people who had written him Christmas letters. Other people soon followed his example, although it took some time for the greeting card to become a mass-market business.

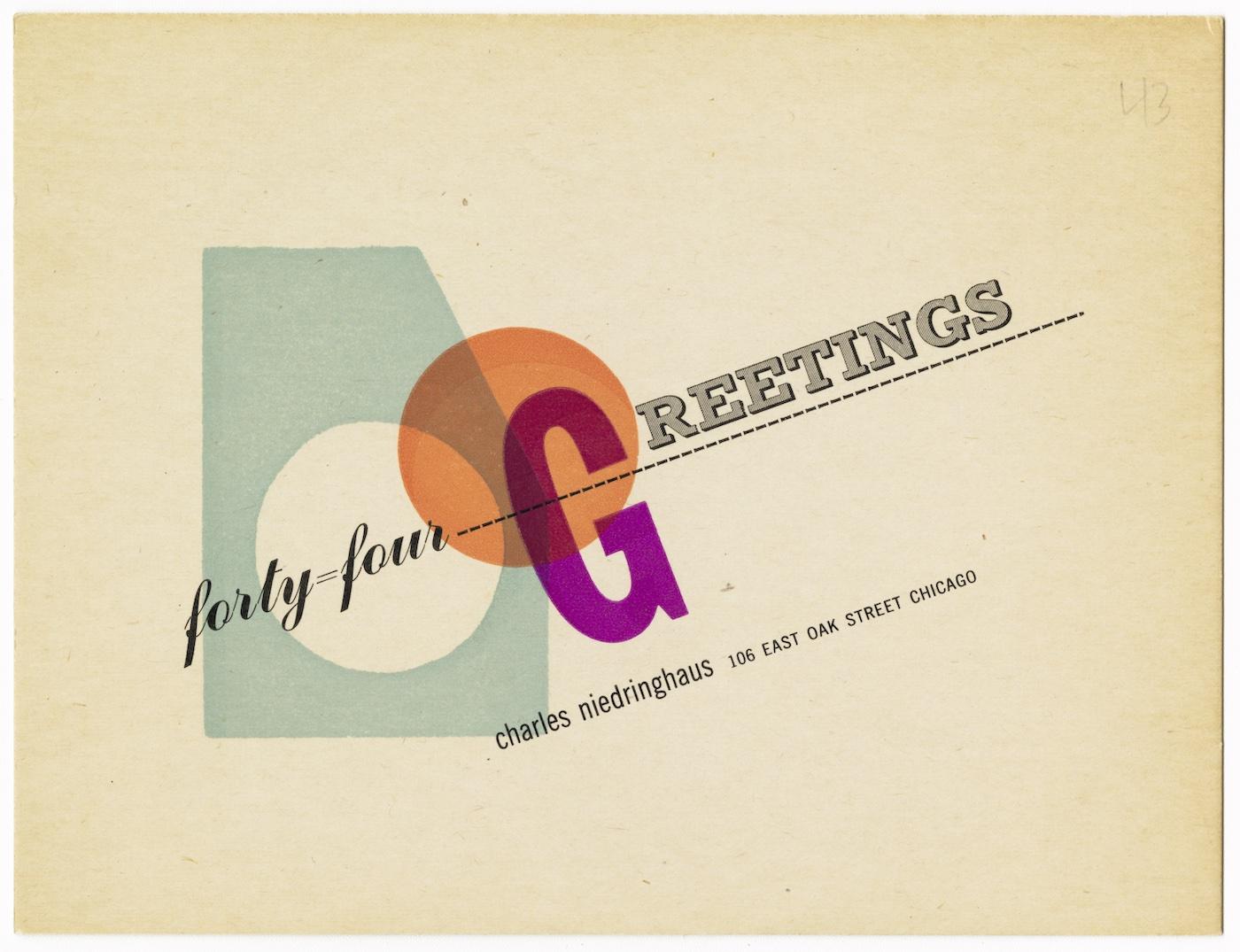

You can observe the development of design trends over the decades via greeting cards. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-182739; Frank Barr, designer

You can observe the development of design trends over the decades via greeting cards. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-182739; Frank Barr, designer

But by the late nineteenth century, Christmas cards had become increasingly popular in both England and the United States. The introduction of cheap postage around Cole’s time and the expansion of the postal service had also increased mail correspondence. “It’s about good manners and creating and maintaining social bonds,” Wroblewski says, while also saving time. Even today’s popular photo cards with a quick summary of people’s lives serve the same purpose, she points out. “It’s a way of transmitting some crucial sharing about what’s going on in their lives, but doing it in a manner that they can get it out to a lot of different people in a timely manner.”

Not that nothing about greeting cards has changed over the decades, as you can see from the museum’s collection. Earlier cards tend to have detailed winter scenes: “a snowy village, horses, perhaps some winter sports, caroling, food—what I think of as Dickensian Christmas,” Wroblewski says. Santa only begins to appear, at least in the History Museum collection, in the early twentieth century.

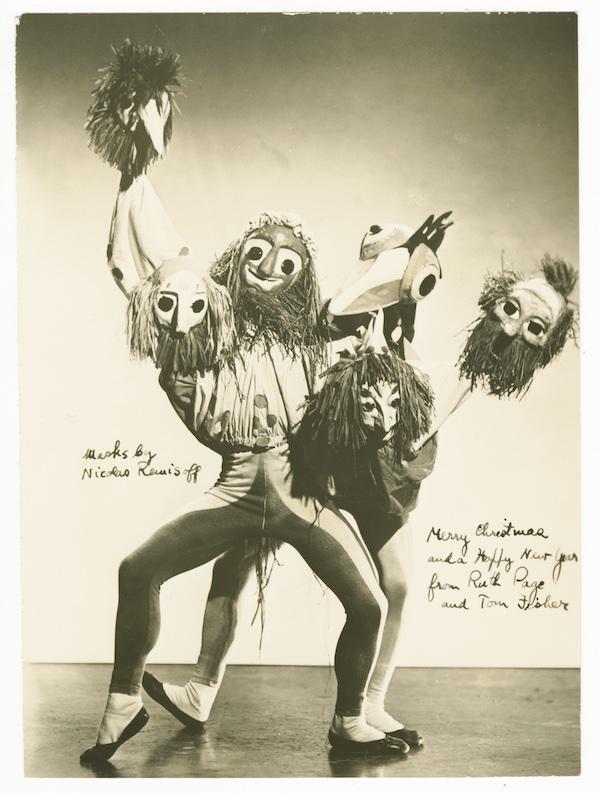

Some cards in the History Museum's collection are incredibly personal, like this one from choreographer Ruth Page. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-095433

Some cards in the History Museum's collection are incredibly personal, like this one from choreographer Ruth Page. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-095433

As time progresses, you can observe the evolution of artistic and design trends reflected in the style of the cards. By “the ‘30s, ‘40s, and ‘50s, you start to see a lot more adventure in graphic design,” Wroblewski says. A circa 1944 card designed by the Chicago-based Charles Niedringhaus in the collection is strikingly simple, with just a few bold colors and shapes.

And not all greeting cards are mass-market generics, of course. Another card in the collection, from the choreographer Ruth Page and her husband Tom Fisher, has a photo of dancers holding and wearing masks, directly referencing Page’s work. The 1949 card even notes who made the masks.

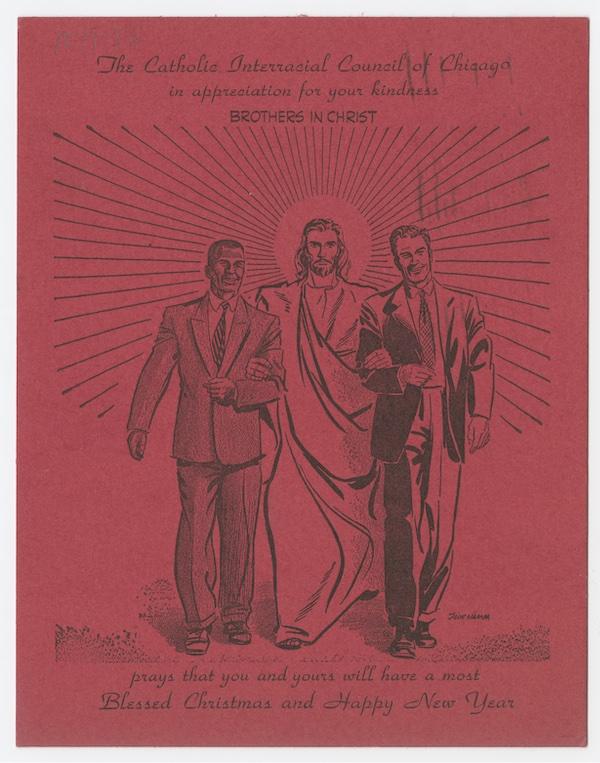

A card from the Catholic Interracial Council of Chicago announces the organization's purpose and values. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-074341

A card from the Catholic Interracial Council of Chicago announces the organization's purpose and values. Image: Chicago History Museum, ICHi-074341

Other cards in the collection announce the purpose and values of the organization that sent them, like one from the Catholic Interracial Council of Chicago that depicts Jesus walking arm-in-arm with a white man and a Black man.

As for Wroblewski? She sends a New Year’s card. “That’s a date that’s relevant to everyone, for the most part,” she explains. “And on a tactical level, it gives me a little extra time.” Because even though the holiday greeting card was invented to save time, it itself has become its own sort of obligation that takes up time.