“The rice is getting cold!” Gary Nakai’s father would admonish his children with this phrase as they pounded rice into mochi every year. Everything about the process of mochitsuki, or making mochi, is a race against the cooling of the rice: the usu, or mortar, is kept warm with a towel soaked in hot water, while the wooden hammers known as kine that are used to pound the rice are kept in warm water; the individual grains of rice must be quickly mashed into a single volume that has less surface area and thus loses less heat; that glutinous dough has to be rapidly beaten, turned, and stretched into a smooth mass to be pinched off into individual pieces for consumption.

The Japanese Tradition of Pounding Rice into Mochi at the New Year

Get more recipes, food news, and stories by signing up for our Deep Dish newsletter.

Every new year, barring those during the pandemic, the Japanese American Service Committee (JASC) and Tohkon Judo Academy host a community event to make mochi, a chewy snack of glutinous rice pounded utterly smooth. We documented the tradition and process of transforming individual grains of rice into firm dough at the JASC’s Uptown location.

All photographs by Sandy Noto for WTTW.

If the rice gets cold, the wondrously springy, even texture of the mochi will be broken by clumps and bumps.

Mochi is traditionally prepared in Japanese communities at the New Year, or Oshogatsu. Whereas Japanese Americans like Nakai once typically made mochi at home amongst their families, according to Michael Tanimura, now mochitsuki more often occurs in a large communal setting, such as at the JASC and Tohkon Judo Academy’s Kagami Biraki celebration in January. (More on Kagami Biraki later.)

Tanimura is in charge of steaming the 80 pounds of rice for mochi at JASC, while Nakai is the “mochi meister,” in Tanimura’s words, leading the pounding of the rice at three annual mochitsuki events around Chicago. (JASC usually uses 100 pounds of rice, but the pandemic has shuffled all expectations; Tanimura was unable to take part in this year’s celebration because he had COVID.)

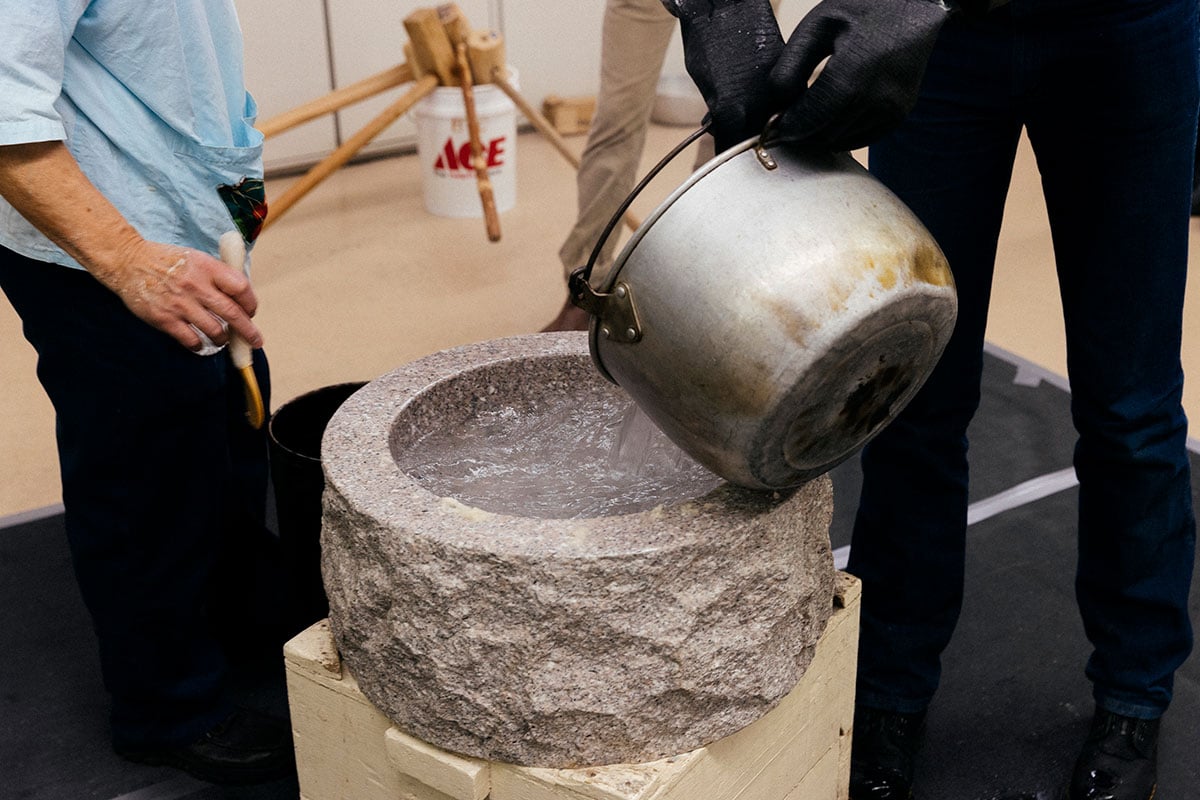

The mochitsuki process is relatively simple, if nuanced. A special strain of rice with a slightly higher sugar content is soaked overnight in water. It’s then cooked in stacked wood and bamboo steamer trays over large pots of boiling water until it’s soft but still has some resistance. The steamed rice is dumped into the warmed usu—Nakai heats his 264-pound granite mortar beforehand with an electric heater, and sometimes uses boiling water too.

Up to four people mash the rice with the cylindrical heads of their kine, walking around the usu as they push and grind the grains into a sort of dough.

They then stand in a circle around the usu and pound the dough with alternating strokes of kine: skilled pounders leave barely a break in the rhythm between each hit. The person in charge occasionally yells “Matte!”—stop—and reaches in to adjust the mochi, moistening or turning it so that it is evenly pressed into a consistent mass.

As the mochi comes together, the turner darts in more and more frequently, leaving just one person to pound. The rhythm can be so fast that it’s amazing fingers aren’t smashed under the kine.

When it’s perfectly smooth, the mochi is taken out of the usu and coated in cornstarch.

Small portions are pinched off and then either stretched to accommodate a filling such as sweet bean paste, chocolate, or strawberries, or simply rolled into an unbroken disc. Americans might be most familiar with mochi as a coating for ice cream, but you won’t find that preparation at JASC.

“Back in Japan, making mochi the traditional way is seen as inefficient, but here we cling to traditions,” says Michael Takada, the CEO of JASC. “We love being able to uphold traditions at JASC so that people new to them can experience them, including non-Japanese people.”

While mochi is traditionally prepared right around the New Year, at JASC mochitsuki is folded into a Kagami Biraki celebration hosted by Tohkon Judo Academy, which shares a space with JASC on Clark Street in Uptown. (JASC has just announced that they are selling that building, which they have occupied since 1970, and moving to a new location at 5700 N. Lincoln Avenue. Tohkon will move to Edgebrook.)

Kagami Biraki typically falls on January 11, and was adopted by the founder of judo as an important ceremony for dojos. When mochi is made at the New Year, two large discs are stacked on an altar with a tangerine on top. The kagami mochi sits out until January 11, when the now-dry discs are broken and often eaten in a soup called ozoni. “It’s a way to welcome the new year, good health, good fortune, and Tohkon Judo has been doing it as long as there’s been a Tohkon Judo,” says Tanimura.

The Kagami Biraki at JASC and Tohkon also involves a purification of an altar and the entire building, as a way to have an auspicious start to the year. A taiko drumming performance and judo demonstration round out the celebration.

But the mochitsuki is the only part that brings everyone together: anyone can take part. Before taking the pounded mochi out of the usu, Nakai often allows children to take a turn at it with a kine, even if they need his help holding the mallet.

The final round of mochitsuki was just for women, with even Nakai eventually being replaced as turner.

Anyone who attends can leave with a little paper plate of mochi as well, to be eaten with grated daikon, soy sauce and sugar, kinako (roasted soybean powder), or simply plain, enjoying the delightfully unique texture. Now that the mochi is finished, you can even let the rice get cold.