The Two Paleontologists Who Had a Bone to Pick with Each Other | Detours | Prehistoric Road Trip

Bribery. Theft. Sabotage. Ruined reputations. It sounds like a television drama, not the events surrounding some of America’s first paleontologists.

The “Bone Wars” between paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh was a dramatic, well-documented, and decades-long tiff between two leaders in their field. “Tiff” may actually be putting it too lightly, as the two men who made major discoveries and gigantic strides in paleontology set out to outdo and ultimately destroy the other.

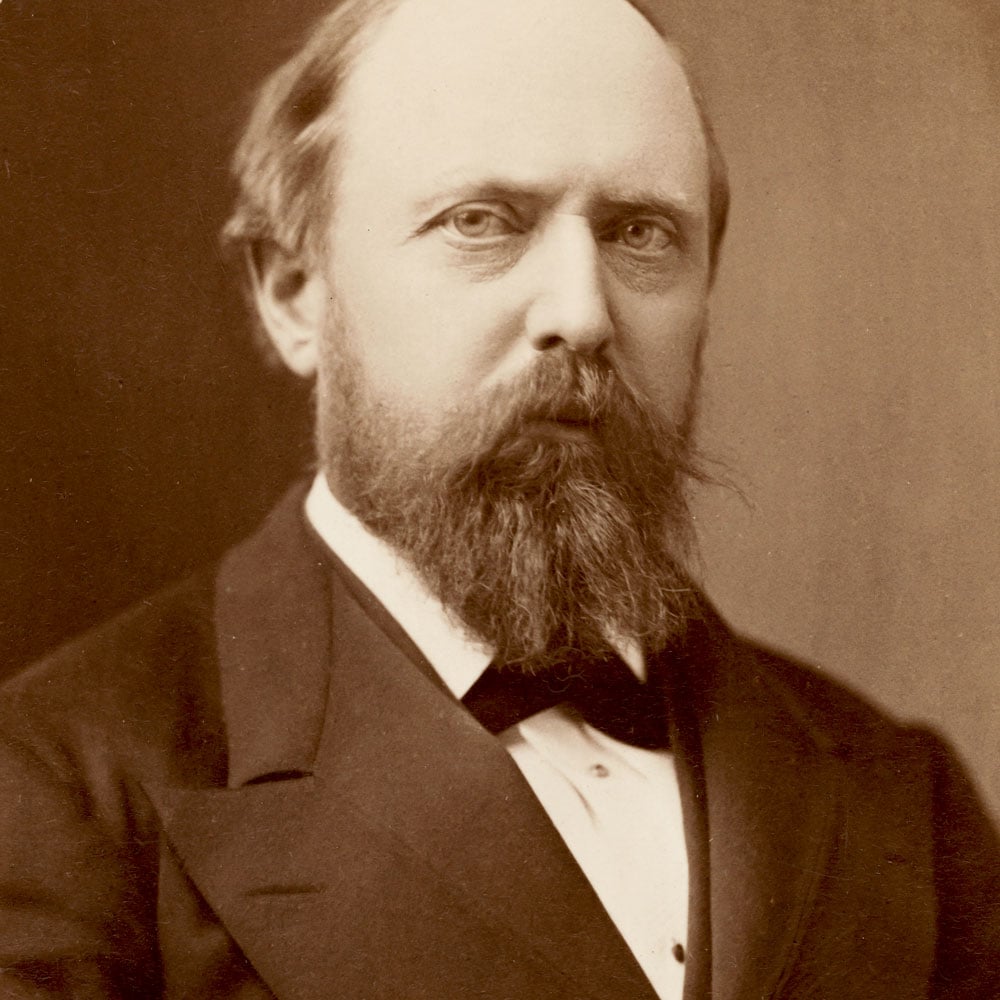

Othniel Charles Marsh was born in 1831 in Lockport, New York to a family of farmers. Marsh was able to attend Yale University thanks to his wealthy uncle, George Peabody. He went on to study paleontology – a relatively new field at the time – and anatomy in Germany. When he returned, he became the first professor of paleontology in the United States, according to Encyclopædia Britannica. He worked at the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University.

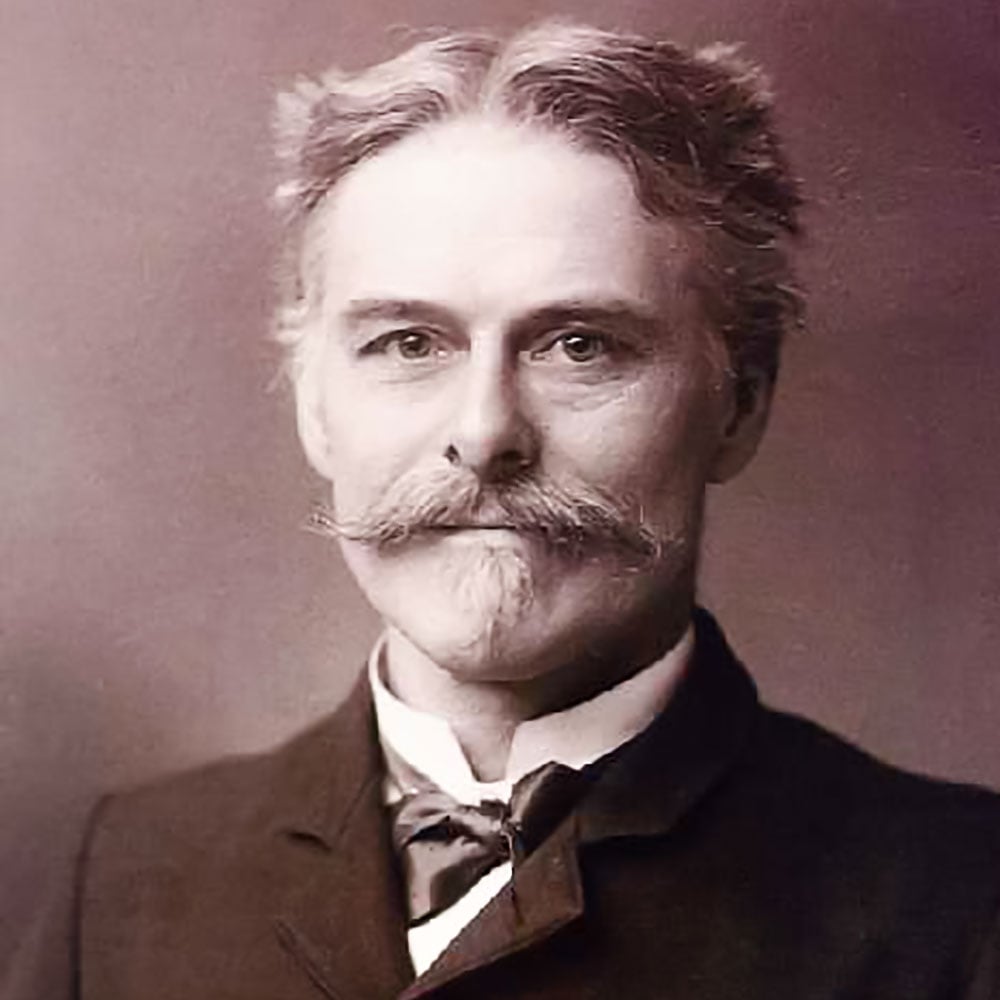

Edward Drinker Cope was born in 1840 in Philadelphia to a wealthy family. Cope showed an interest in science at an early age, though he never had formal training as a paleontologist. Cope studied under Joseph Leidy, a professor of anatomy who discovered the first dinosaur remains in the United States. According to Mark Jaffe’s book, The Gilded Dinosaur, which chronicles the feud, Cope’s father sent him to Europe, likely to end a love affair his father deemed unsuitable and also possibly to avoid being drafted in the Civil War. In Europe, he met Marsh, who was a graduate student at the time. Cope became a professor of zoology at Haverford College (only after his family’s connections got him an honorary master’s degree so he could get the job) and worked for the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia.

Othniel Marsh was the first professor of paleontology in the U.S. Photo: Courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

Marsh and Cope’s relationship was friendly at the beginning. According to Jaffe’s book, they swapped letters, fossils, and manuscripts and seemed to be friends. The two even named a couple of new species after one another. Cope named an amphibian fossil Ptyonius marshii. Marsh returned the favor, naming a giant marine creature Mosasaurus copeanus. But Marsh’s gesture was tinged with betrayal, and things quickly became competitive.

As it turns out, Mosasaurus copeanus came from a quarry in Haddonfield, New Jersey that Cope was working in. Cope had shown Marsh the quarry in 1868, but Marsh struck a deal with the landowner to come to Marsh with any new fossils first.

Not long after the double-crossing quarry debacle, Marsh also struck a blow to Cope’s ego. Cope had been working on reconstructing an Elasmosaurus, a genus of the marine reptile plesiosaur. In his rush to publish to compete with Marsh, Cope made a humiliating mistake: he put the head at the end of its tail, rather than atop the neck. Marsh pointed out Cope’s error. It didn’t go well. Cope was so humiliated that he tried to buy all the copies of his journal article that had widely distributed the inaccurate findings.

From then on, Cope and Marsh were rivals. And the rivalry became only more bitter and destructive in the years that followed.

Much of the Bone Wars played out in Como Bluff, Wyoming, as well as other parts of the western U.S. – especially the Morrison Formation. The Morrison Formation is a unit of sedimentary rock spanning eight states, from Montana to New Mexico. It preserves much of the Jurassic period as far back at 200 million years ago. The discoveries in the Morrison Formation have taught us that the Jurassic was lush and green and that mammals, pterosaurs, crocodiles, dinosaurs, and even small amphibians lived during that time.

Edward Cope studied under the man who discovered the first dinosaur bones in the U.S. Photo: Courtesy of the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

With so many bones, the Morrison Formation was destined to become a battleground. The Bone Wars started in earnest in 1877 when a geologist named Arthur Lakes discovered massive dinosaur bones near Morrison, Colorado. He tried to alert Marsh to his findings, but Marsh was slow to respond, because at the time he was more interested in mammal fossils than dinosaurs, according to Jaffe. So Lakes instead sent some specimens to Cope. That got Marsh’s attention, and Marsh hired Lakes and sent more of his crew to Colorado to begin the mad dash for dinosaur bones.

Over the next decade and a half, a gold-rush-type of mania consumed Cope and Marsh, who constantly tried to outdo one another. Their tactics became shady. Marsh supposedly bribed people to work for him instead of Cope, hired spies to snag intel on the findings of his nemesis, and even wrote covert letters and telegrams giving Cope the code name, “B. Jones.”

Cope continued his bad habit of rushing to publish his discoveries and even bought his own scientific journal to keep up with his publishing load. According to the PBS American Experience recounting of the Bone Wars, Cope published 76 academic papers between 1879 and 1880 – and a staggering 1,400 articles during his lifetime. The two men found so many bones that their respective institutions didn’t have a place to store them all. There are even some accounts that claim that Cope and Marsh were so competitive, they stole from one another and destroyed any leftover bones from a dig site just to prevent them from falling into the “wrong hands.”

Cope, as it turns out, wasn’t the only one to make an embarrassing mistake in the rush to outpace his adversary. Though both men (and many other early paleontologists, for that matter) made many errors in the publications of their findings – such as confusing a younger version of one species for a new species altogether – Marsh made one of the biggest ones. When Marsh discovered a long-necked dinosaur in 1877, he named it Apatosaurus. But the incomplete specimen was missing its skull, so Marsh guessed that a skull found elsewhere belonged with the Apatosaurus. Unfortunately, it was actually the skull of a Camarasaurus. When he examined another long-necked fossil a couple of years later, he named that one Brontosaurus. But it was actually just an Apatosaurus, this time with the correct skull. Despite the fact that other paleontologists discovered and corrected his error a few decades later, both names stuck, which is why you might still hear both today.

As the two smeared one another in publications, the biggest casualties were Cope and Marsh themselves. By 1882, Marsh had become head paleontologist at the new U.S. Geological Survey. His political connections allowed him to financially cut off Cope from the government funding that was essential to supporting his work. He even tried to seize Cope’s fossils on the grounds that they were the government’s property. Cope fought back in a particularly vicious way in 1890. He worked with a reporter who published a story in The New York Herald that accused Marsh of plagiarism and mismanagement of government money, among other things. Cope and Marsh used the press as their final battlefield, going back and forth for weeks. Their reputations were all but destroyed.

In the end, Congress cut the budget for the U.S. Geological Survey’s paleontology department and ousted Marsh, also forcing him to hand over his fossil collection. The already-penniless Cope suffered, too, as no one wanted to purchase his fossil collection. Someone eventually bought part of his collection, but he died at age 56 in 1897. Marsh died two years later at 67, also broke.

What’s the bright side in this tale of scandal, scientific error, and ruined careers? It’s safe to say there was no real winner of the war. But despite everything, Cope and Marsh found more than 130 new dinosaur species. Between them, they discovered now-famous dinosaurs, such as the carnivorous therapod Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, Triceratops, Diplodocus, Apatosaurus (or, um, Brontosaurus), and many, many more.