Colorado River Aqueduct

Colorado River Aqueduct

Providing much of the drinking water for southern California, the aqueduct – another Depression-era public works project and the brainchild of L.A.’s controversial water department superintendent William Mulholland – travels from the river, across the desert and five mountain peaks before descending into Los Angeles.

Long before the first celebrities plunged their hands into wet concrete on the Walk of Fame, before bodybuilders pumped iron on Venice Boardwalk, and before the rich and famous flocked to luxury boutiques on Rodeo Drive, Los Angeles was just a sleepy, little, farm town nestled along the Los Angeles River. Its estuary quenched the city’s thirst for more than a century.

But in the early 1900s, its river became depleted as LA’s population began to grow.

William Mulholland “felt it was his duty” to solve that problem, according to April Summitt, dean of La Sierra University’s College of Arts and Sciences and author of Contested Waters: An Environmental History of the Colorado River.

Mulholland, who had taught himself engineering, had gone from ditch digger for a private water company to the superintendent of LA’s water department in eight years.

“He watched the levels drop, and he watched the population absolutely grow exponentially, and so he was worried, fairly early on, that the city was going to run out of water,” said Summitt.

Mulholland tried to convince residents to conserve water. He installed meters and promoted planting more foliage in the city to assist with ground water retention and recharging the aquifer. But none of it was enough.

Eventually, Mulholland and Mayor Fred Eaton built an aqueduct to transport water from the Owens River, 233 miles away. Built between 1908 and 1913 at a cost of $23 million, the Los Angeles Aqueduct ignited the California Water Wars and turned the lush Owens Valley into a barren desert.

“Towns began to shut down,” said Summitt. “A bank collapsed. People moved out, sold their land, and got off a dying ship.”

But it did solve LA’s water problem, albeit temporarily. LA continued to grow. And so in time, Mulholland began searching for another source of drinking water for his customers. He started eyeing an even bigger prize, the biggest in the region: the mighty Colorado River.

“Everybody was after the Colorado at that point, said Summitt. “Mulholland knew that if you didn’t hurry up and get the water and start using it, you would probably lose it.”

He hired several teams of surveyors and sent them out to do a comprehensive survey of the large swath of land between LA and the Colorado. Mulholland often went out with them. Eventually, they found a workable route for an aqueduct, beginning 150 miles downstream from the Hoover Dam.

But before construction could begin, Mulholland’s career was suddenly destroyed. The St. Francis Dam, which Mulholland had designed, collapsed on March 12, 1028 – just hours after he inspected the site. The catastrophe took between 400 and 600 lives.

According to the Los Angeles Times, “Water engulfed whole towns, dozens of ranches…It demolished 1,200 houses, washed out 10 bridges and knocked out power lines. Bodies would wash ashore as far south as San Diego.”

Mulholland retired in November of that year and retreated into relative solitude.

But by that time, the Colorado River project had gained enough momentum to continue without him. Mulholland had already laid the groundwork to create the Metropolitan Water District (MWD), made up of representatives of the various cities throughout Southern California who would oversee and benefit from the project. In 1931, the MWD decided to officially adopt Mulholland’s route, and construction began in January 1933.

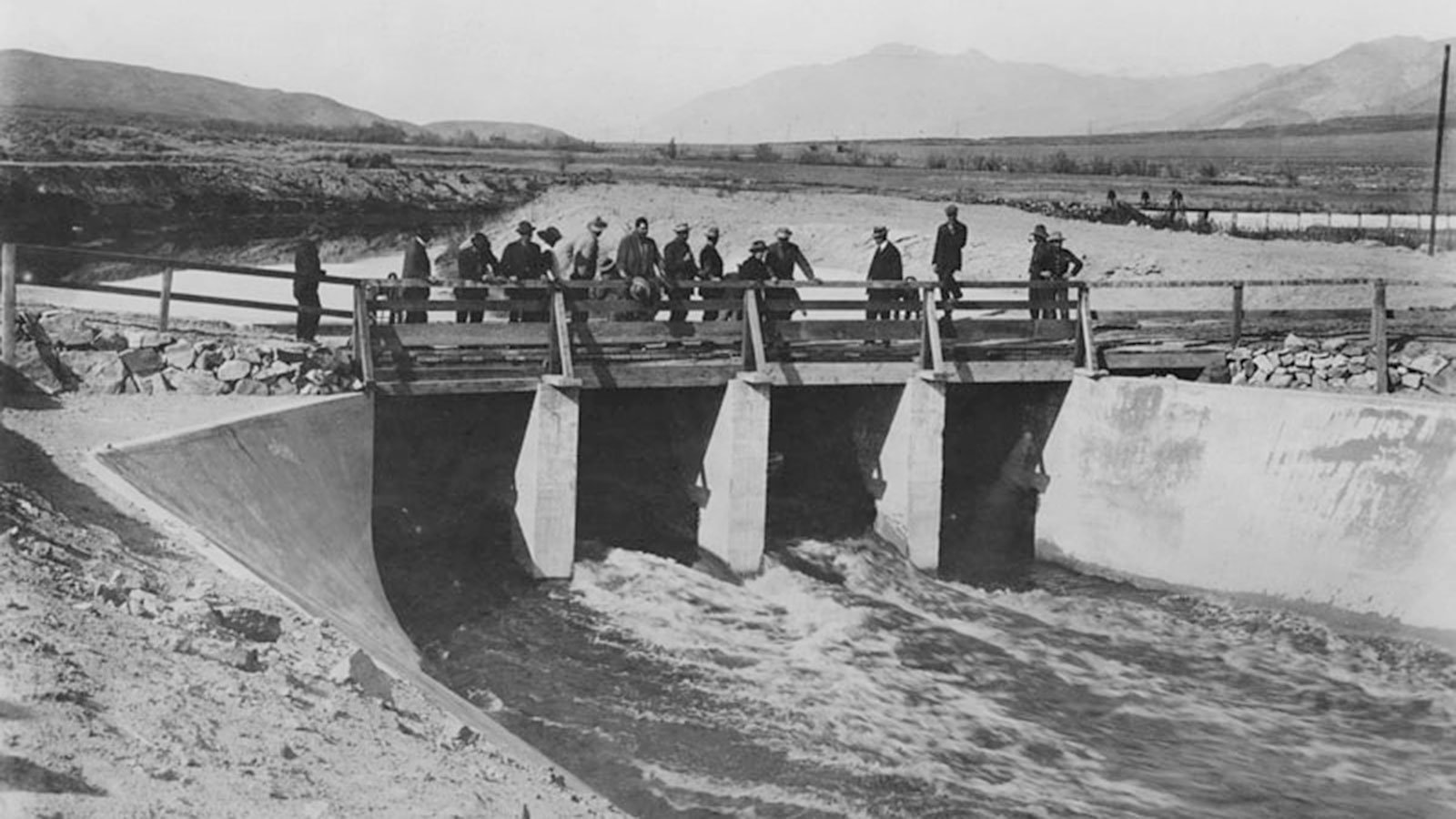

To get to LA, the aqueduct would have to make it through miles of desert and over five mountain peaks. An old-fashioned aqueduct, designed so that the water is always flowing downhill, wasn’t going to cut it. Instead, the MWD needed to construct a dam and a series of pumps and siphons to help propel the water. It would all begin with the Parker Dam, located on a portion of the Colorado River that carves the border between Arizona and California. The dam would effectively straddle the two states.

But officials in Arizona weren’t too happy with the idea of Los Angeles siphoning off their water or building on their land in order to do it.

“Arizona ends up declaring war on California,” said Summitt, “or at least they like to think that that’s what they were doing.”

Soon after construction began, Arizona Governor Benjamin Moeur called up the Arizona National Guard. Six soldiers arrived in Parker, Arizona, to observe construction. When workers began building a trestle bridge from the California side, Moeur decided it was time to declare martial law. He sent 100 armed troops to the Arizona shore with orders to physically prevent construction of the dam on Arizona soil.

“Moeur was determined,” said Summitt, who explained that the Arizona governor tried to amass a navy to send into the Colorado River. “The problem was Arizona didn’t have any boats for a navy. They could find only a couple of old ferry boats...He sent them out into the middle of the river to do reconnaissance and they got stuck...probably on a sandbar. And the embarrassing part was that they had to ask for [the] help of the California construction crew on the other side.”

“So enemy California helped rescue the Arizona troops that were stuck in the middle of the river,” said Summitt. “And the newspapers had a field day.”

US Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes halted construction, and Governor Moeur recalled the Arizona National Guard and turned to the courts to resolve the matter.

The case made its way to the Supreme Court which sided with Arizona in April 1935. But eventually, political compromises were made, Moeur relented, Congress intervened – and work resumed.

The aqueduct project provided jobs for approximately 30,000 people at the height of the Great Depression, employing roughly 10,000 at any one time.

The completion of the Parker Dam in 1938 created Lake Havasu, the aqueduct’s main holding reservoir. After that, workers dug more than 90 miles of tunnels, built nearly 85 miles of buried conduits and siphons, and installed five pumping stations. Finally, where the aqueduct ends at the eastern edge of Los Angeles, they built yet another manmade lake. The last reservoir sits just above LA, its water traveling from there to homes and businesses throughout the region.

Since 1941, the Colorado River Aqueduct has been supplying fresh water to homes, businesses, and industries throughout Southern California, allowing some of America’s largest and most vibrant cities to bloom in the desert. The population of the six counties served by the MWD grew fivefold in in just the first five decades after the aqueduct was built, from 3.5 million in 1939 to 17.5 million in 1993.

But for the once-mighty Colorado River, this has all come at a price.

“It is 9 percent lower than it used to be just a few years ago,” said Summitt. “The Colorado River is like a plumbing system; the way we have tapped it up and down its stream and drawn so much water off of it,…even in the best of climate conditions, it could go completely dry.”

But she said the threat of water scarcity is helping to build a growing effort to conserve water and seek out solutions for the region’s future.

“The good news is we are thinking about those kinds of issues now in a way that we weren’t perhaps twenty years ago,” said Summitt. “I’m very hopeful about the new awareness that we all have about our limited resources.”