Eads Bridge

Eads Bridge

In the age of the railroad, the Mississippi River had become a barrier to train traffic, until an ingenious young man named James Eads created the first steel bridge, ushering in a new steel age for engineering, architecture, and manufacturing.

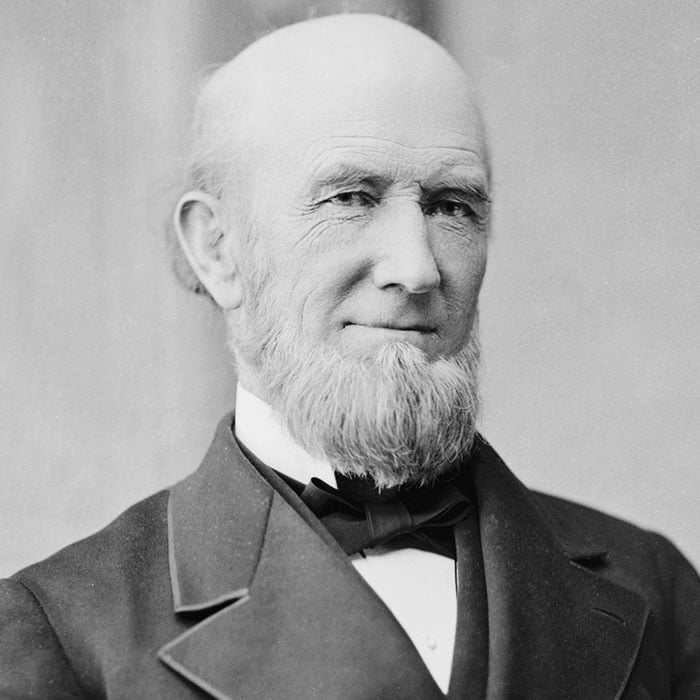

“The thing you need to know about James B. Eads,” says architectural historian Lynn Josse, “is that he can do anything he sets his mind to.”

And James B. Eads set his mind to greatness.

According to his grandson, he built his first steam engine at the age of 11. Although he stopped attending school at a young age to help support his family by selling apples in the street, he quickly went on to a more lucrative job in a dry goods store, where he is said to have devoured the proprietor’s books on science and engineering in his spare time.

At the age of 22, after spending six years working on the Mississippi and seeing several boats – including one that he was working on – hit snags and sink, Eads designed a salvage boat equipped with a diving bell and an air tube so that he could walk along the river bottom and recover treasures down below.

With what Josse calls his “salesman-like personality,” he convinced two powerful local businessmen to support his endeavor.

“Eads says, ‘Here’s a design for a boat; let’s build it,’” said Josse. “And these two businessmen say ‘Okay, 22-year-old James B. Eads, who’s never built a boat before. We’ll go ahead and do that. Here’s our money.’”

He later convinced the US Navy to let him design and build several ironclad steam-powered warships during the Civil War.

And he followed a similar script soon after when he designed his first bridge, which would be the longest arch bridge in the world. Except this time, there were vocal skeptics.

“There were doubters from the very beginning. One of the country’s most famous bridge engineers said, ‘I want nothing to do with this,’” said Josse.

But the project was critical enough to the city of St. Louis that he and his supporters forged ahead.

St. Louis desperately needed a railroad route across the river. As a port city, St. Louis owed its very existence to the Mississippi River. But in the age of the railroad, that same river became a barrier. Trains would come up to the river’s eastern edge, load their cargo onto a ferry, and then ship it across the river and load it onto new trains in St. Louis.

Chicago, meanwhile, was surpassing St. Louis as the economic center of the Midwest.

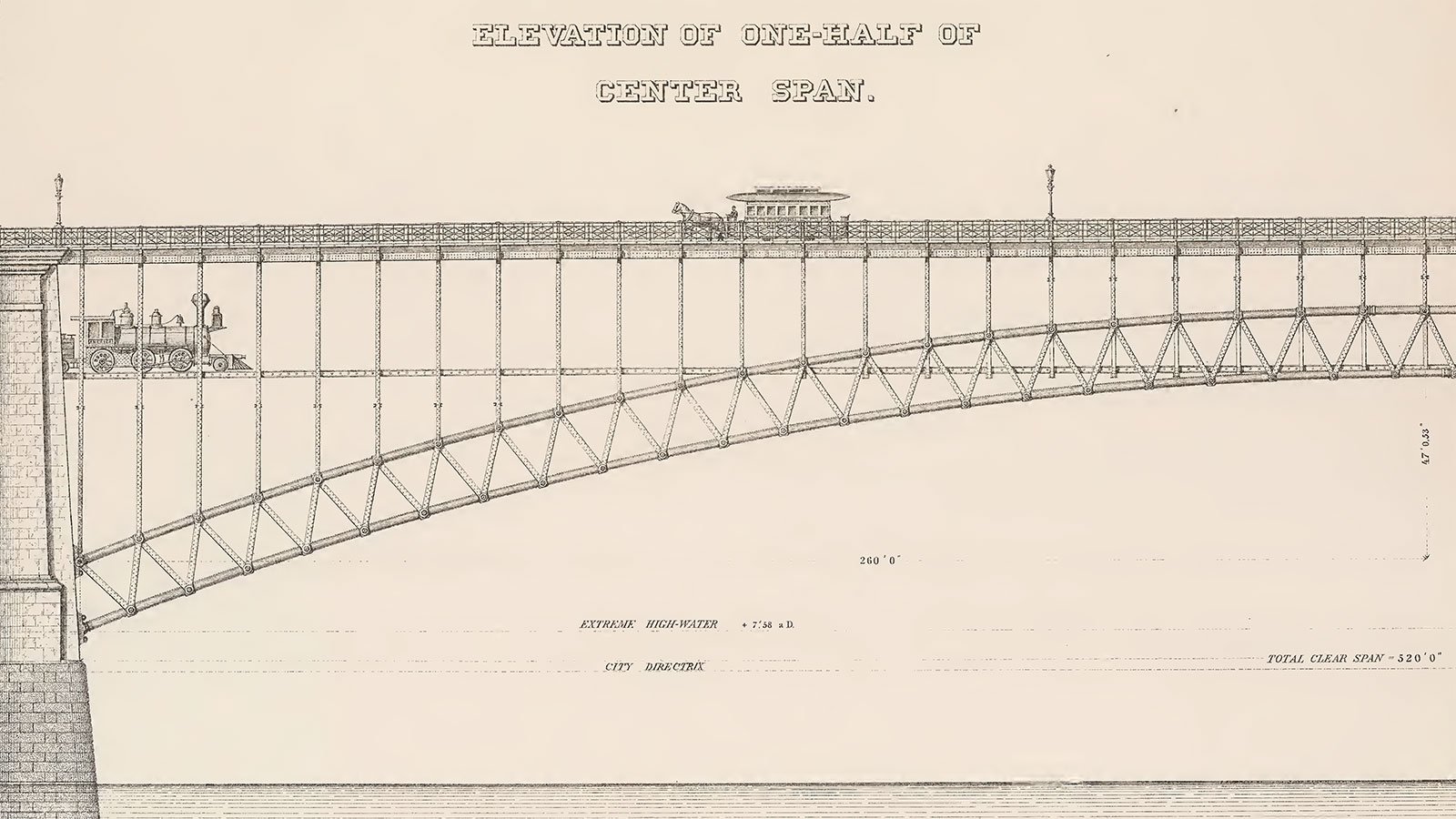

With his roots in the shipping industry, Eads was determined to build a bridge that would meet the city’s competing needs. His design called for giant arches that would support the weight of the bridge from below, while still leaving ample room for boat traffic and making it the long distance across the Mississippi: nearly a third of a mile.

Many doubted whether the amateur bridge builder’s enormous arches would hold up. But Eads had a solution: steel. The strong, inexpensive, and relatively lightweight alloy had never been used as a large-scale building material, but Eads believed it could be perfect for his bridge, and recent innovations allowed for the mass production of a stronger steel than previously available.

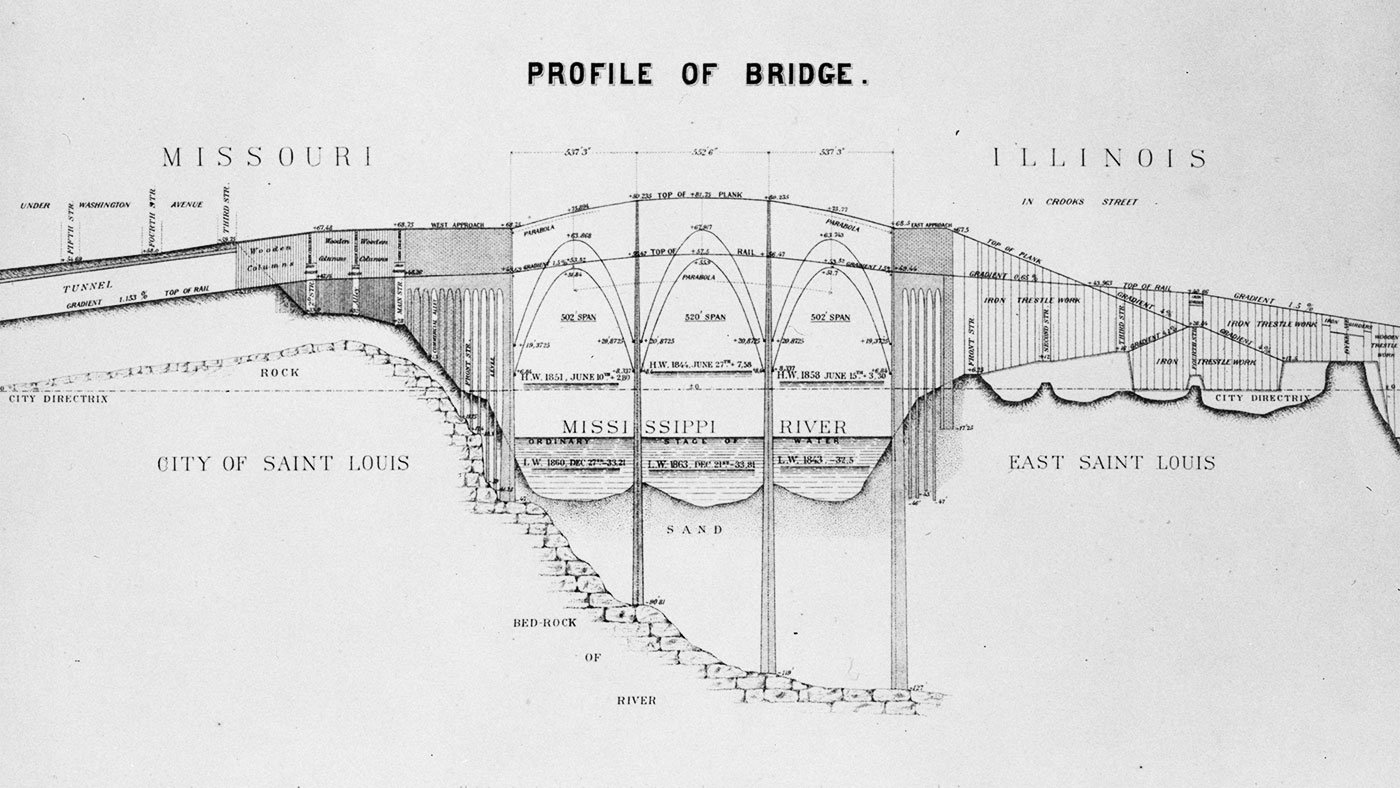

But Eads’s biggest challenge lay below the water. To ensure the bridge would be stable in the swift currents of the Mississippi, Eads believed that his stone piers needed to be anchored to bedrock, more than 100 feet below the water’s surface.

Many people doubted him, saying he didn’t need to dig that far. But he was stubborn.

“James Eads knows the bottom of the riverbed better than anybody else in the country, and he knows how changeable the bottom of the river is,” said Josse.

Eads had an idea for a contraption that could make it possible: a pneumatic caisson. In an adaptation of a technique he observed in France, Eads designed a large, armored container, with an opening at the bottom so that it could be pushed down into the water, trapping air that was being pumped into the chamber.

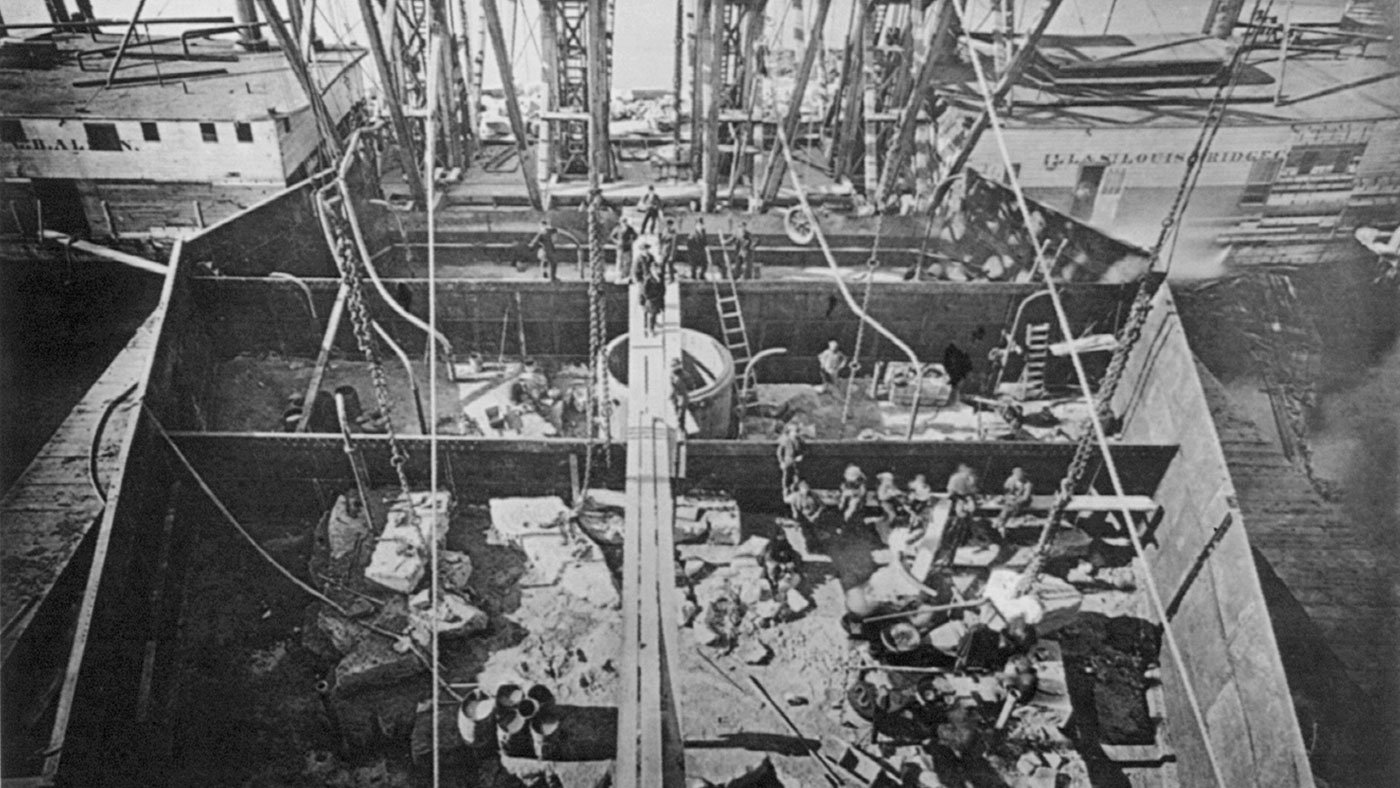

Workers known as “submariners” would descend a staircase to the river’s bottom, where air was pumped into the caissons. Once inside, they would dig the mud and sand from under the caisson, shoveling it into a sand pump, which lifted it to the surface and dumped it back into the river. The caisson continued to press down through the river bottom until it reached bedrock, where it eventually became the base of the foundation.

In France, the caisson had been used at depths only up to 85 feet. As the caisson sunk deeper and deeper in the Mississippi, more air had to be pumped in to hold back the water, increasing the air pressure. When workers returned to the surface after a long shift, the sudden depressurization sometimes caused deadly gas bubbles to form in their blood. More than one hundred workers got sick and at least a dozen died of decompression sickness, also known as “the bends,” while Eads and others struggled to understand the mysterious illness.

By May 1874, the bridge was completed and opened to foot traffic. Still, many questioned whether the steel bridge was safe to cross.

“Even to the end, people were a little nervous,” said Josse. “People expected that it should be bulkier…in order to support the amount of weight that it did. They weren’t used to the amazing properties of what steel could do.”

To lay their fears to rest, a circus owner led an elephant across the finished span. There was a common belief at the time that elephants possessed a sixth sense that would prohibit them from crossing an unstable bridge. As the elephant marched confidently from St. Louis to Illinois, crowds of onlookers cheered.

But for those unconvinced by the elephant, there was a slightly more scientific demonstration. On July 2, 1874, fourteen locomotives filled with water and coal crossed back and forth while throngs of onlookers watched from the bridge above – and the skeptics, of course, watched from the river banks.

Two days later, after an incredible 15-mile-long parade and raucous celebration, the longest arch bridge in the world was open for business.

Unfortunately for Eads and his backers, the bridge didn’t ultimately succeed in supplanting Chicago as the economic center of the Midwest, nor did it settle the ongoing Chicago-St. Louis rivalry. Indeed, it would be more than a decade before the bridge was used regularly by a major railroad company.

But as a showpiece for the possibilities of steel, the Eads Bridge was a huge success. It ushered in a new era for steel in engineering, architecture, and manufacturing. And in that way, its legacy has proved as strong and enduring as the bridge itself.

“When Eads built this bridge, he said that there was no natural force that could take it down; it would stand as long as the pyramids,” said Josse. “It could easily stand another two thousand years.”