New Orleans Risk Reduction System

New Orleans Risk Reduction System

Following the deadly devastation of Hurricane Katrina, the Army Corps of Engineers created a system of safeguards – including a two-mile long, 26-foot high barrier, pumping stations and closable canals – designed to help the city survive increasingly violent storms and rising sea levels and serve as a model for other coastal cities around the world.

New Orleanians have been fighting floods for three hundred years – and almost every one of their attempts have made matters worse.

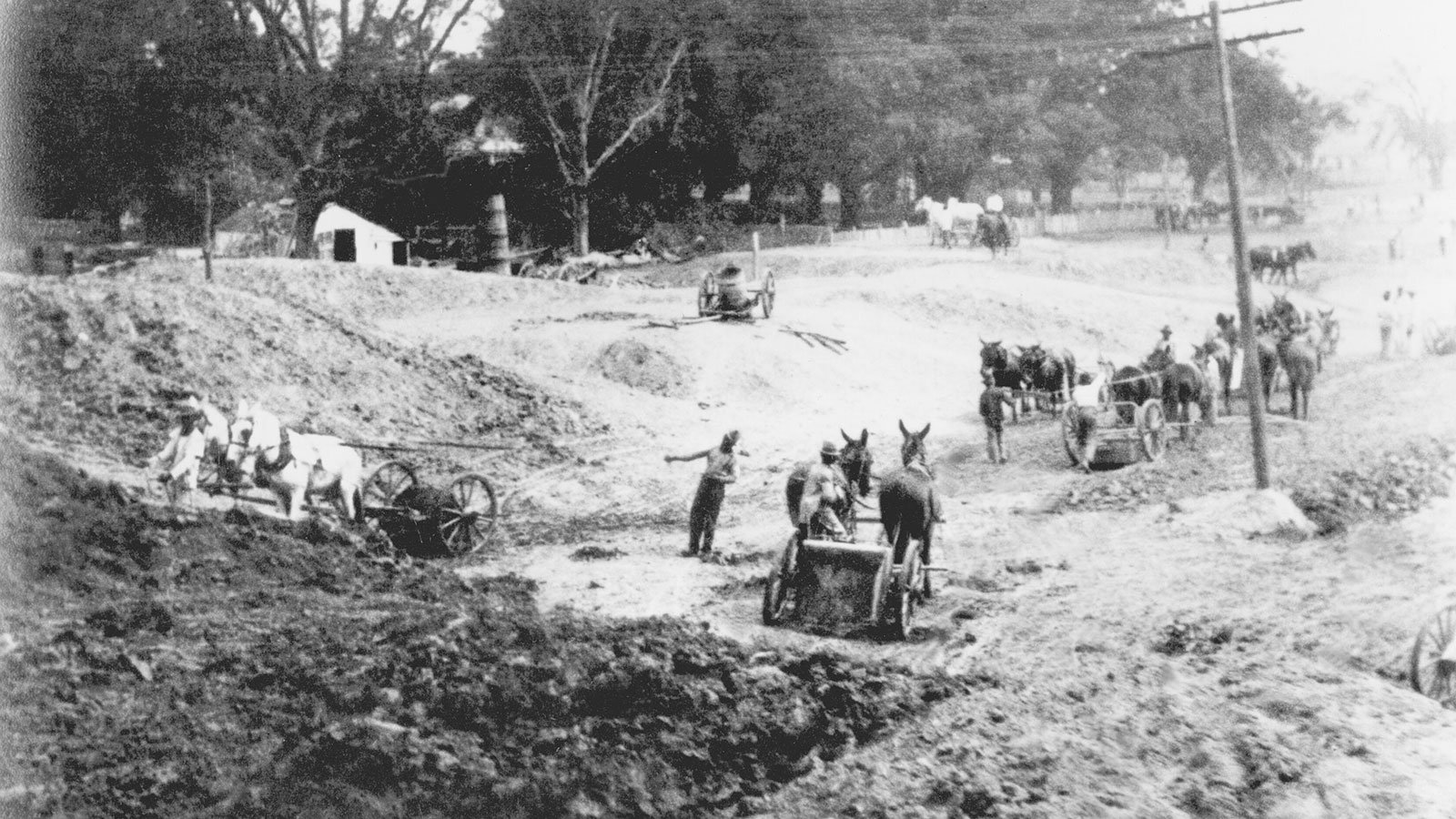

The city saw its first flood just one year after it was founded in 1718 by French explorer and colonial Governor of Louisiana Jean-Baptiste le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville. It immediately began constructing earthen walls known as levees along the city’s riverfront in an effort to contain the source of the floodwater: the Mississippi River, the very thing that made Louisiana such a prime location in the first place.

It wasn’t a great system. “It was the era of localism where each planter, with some government oversight, was responsible for maintaining the artificial levy at the front of each of those plantations,” explained Rich Campanella, professor of geography and architecture at Tulane University. “Now clearly, that is a system that’s only as good as the least diligent planter.”

Eventually, the levees were strengthened and expanded. New Orleanians stopped worrying about flooding from the Mississippi.

But over time, that solution created a new, unforeseen problem: without the natural periodic floods, the river stopped depositing vital sediment that was needed to continually replenish the city’s high ground. Meanwhile the city’s lower-lying neighborhoods continued to flood whenever a heavy storm hit.

So in the nineteenth century, New Orleanians constructed a system of pumps and drainage canals. New Orleans grew once again, and low-lying neighborhoods saw a surge in development.

But over time, as water was drained from the soil, air pockets opened up like tiny cavities. And the city started sinking.

“The good news is, the metro area is still roughly 50 percent above sea level,” said Campanella. “The bad news is we used to be at 100 percent.”

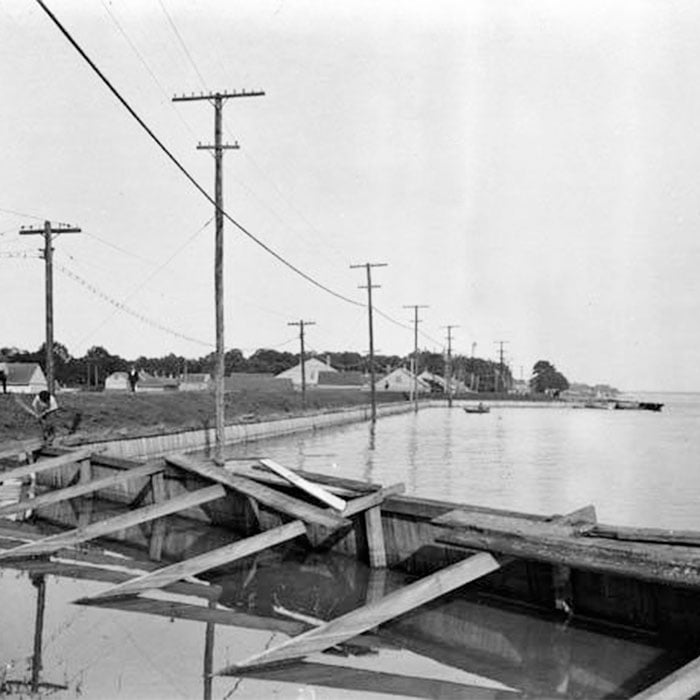

The unintended consequences of these engineering efforts proved tragic in 2005. As Hurricane Katrina swept through New Orleans, a powerful storm surge invaded through manmade navigation channels, and high waters flowed into the very canals that had been built to drain the city.

“There were no closeable barriers on the mouth of those outfall canals – the surroundings of which, by the way, have dropped below sea level,” said Campanella. “What seemed to make engineering and economic sense in one era ended up being an environmental...disaster in another era.”

Compounding the problem during the hurricane, floodwalls proved no match for the rising water.

In all, nearly 2,000 people died as a result of the storm and its aftermath.

Now, a dozen years and $15 billion later, the US Army Corps of Engineers has built an extensive “Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System.”

“It is no longer called the flood protection system, it is no longer called the levee protection system,” said Campanella. “I think this is a good way to communicate risk: that you can’t eliminate it, you can only reduce it.”

Throughout the New Orleans metro area, the system includes 350 miles of strengthened or newly constructed levees and floodwalls and several pumping stations, among them the largest in the world.

The pumping stations have the capacity to drain stormwater as fast as 19,000 cubic feet per second. Put another way, they could fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool in nearly four seconds.

The canals that once let water into the city can now be closed off with gates as big as jumbo jets.

And to protect against storm surges, there is what some have called the “Great Wall” – a two-mile-long, 26-foot-high barrier along the coast.

“What we’re doing is…taking the fight to the storm rather than the storm coming into the city,” said Rene Poche, spokesperson for the US Army Corps of Engineers in New Orleans.

Nevertheless, if a storm like Katrina hit today, says Campanella, “there still would be some water coming in. However… there would be much less flooding.”

Meanwhile, one of Louisiana’s most effective barriers against hurricanes is disappearing. A section of wetlands the size of a football field is lost every 100 minutes, due in part to rising sea levels and increasingly intense storms.

“Coastal wetlands...serve the form of terrestrial friction against storm surges,” said Campanella. “If you have a surge coming in from the sea [and] it hits that land, it’s like a speed bump.”

“Restoring the wetlands is what will turn our current protection of metro New Orleans into something a little bit more long term and sustainable,” he said.

Rising sea levels and ever more violent storms pose a threat not just to New Orleans, but to coastal cities around the world. And the best response, says Campanella, is to employ various strategies – including not only advanced civil engineering, but also environmental stewardship and public policies that will help reduce vulnerability.

“It means making decisions now about risk reduction. It might mean, in some cases, relocating assets, putting in new building policies whereby a critical infrastructure is raised above the grade. I personally hope it means thinking long and hard about developing flood plains.”

Still, as Poche puts it, “Mother Nature is always going to get the last laugh. Mother Nature is Mother Nature.”