Reversal of the Chicago River

Reversal of the Chicago River

As Chicago grew into a major metropolis, its river became an open sewer that fed directly into the city’s water supply. It took a crafty engineer named Ellis Chesbrough to come up with a startling plan: reverse the flow of the river to the Mississippi, toward the city’s longtime rival, St. Louis.

In the mid- to late-nineteenth century, Chicago quickly transformed from a tiny frontier town to a major metropolis. As the city grew, the river became more and more polluted with raw sewage and industrial waste, all of which flowed directly into Lake Michigan, the city’s source of clean drinking water.

Typhoid, dysentery, and cholera jeopardized Chicago’s future. In 1854 alone, more than 1,400 Chicagoans died of cholera.

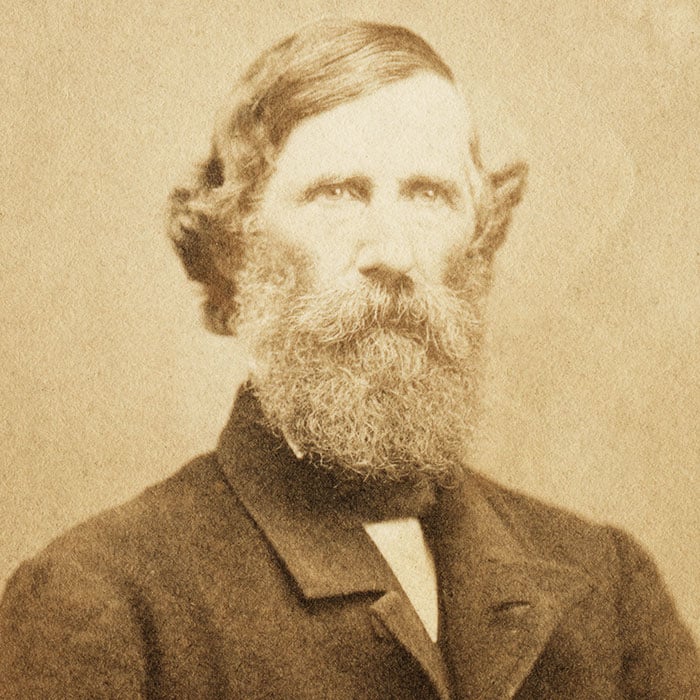

In 1855, Chicago enlisted the help of Ellis Chesbrough to help solve its water crisis. Chesbrough, an engineer who had built Boston’s water supply system, seemed the have just the kind of audacity and vision that Chicago needed.

“Ellis Chesbrough was the kind of guy who would propose things that people, when they’d hear it, they’d go, ‘You want to do what?!?’,” says Tim Samuelson, Chicago's official cultural historian. “He never feared a problem.”

Indeed, Chesbrough’s first couple of solutions were duly ambitious, though perhaps short-sighted.

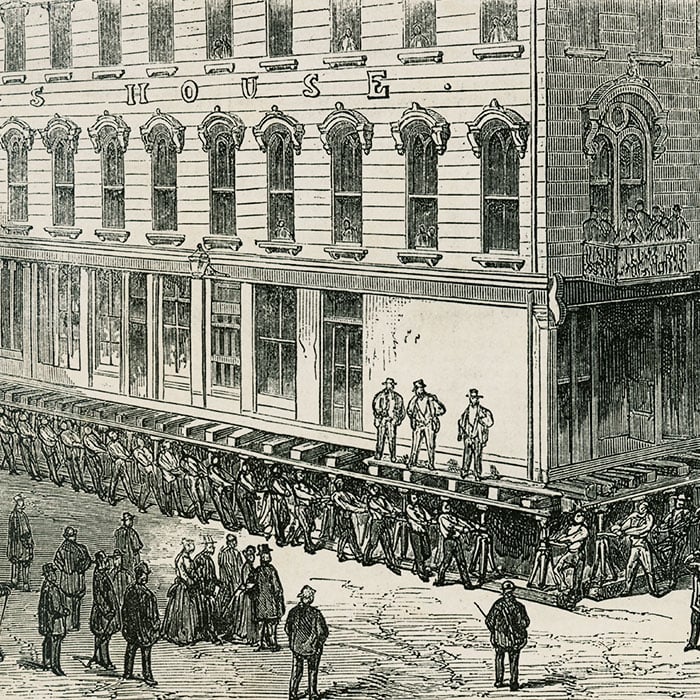

For starters, he designed the first comprehensive sewer system in America. Starting in 1859, small armies of workers raised Chicago homes and buildings by as much as twelve feet. Workers hoisted each of them up individually with dozens of jacks, turned in unison. They then laid sewer pipes down the streets at an incline so that gravity would carry the city’s waste to the river. The pipes were then covered with dirt, and the new streets matched the grade of the elevated buildings. Within a decade, more than 152 miles of sewer pipe was completed this way.

But the sewers still emptied into the river which flowed into the water supply, threatening the health of the city’s residents.

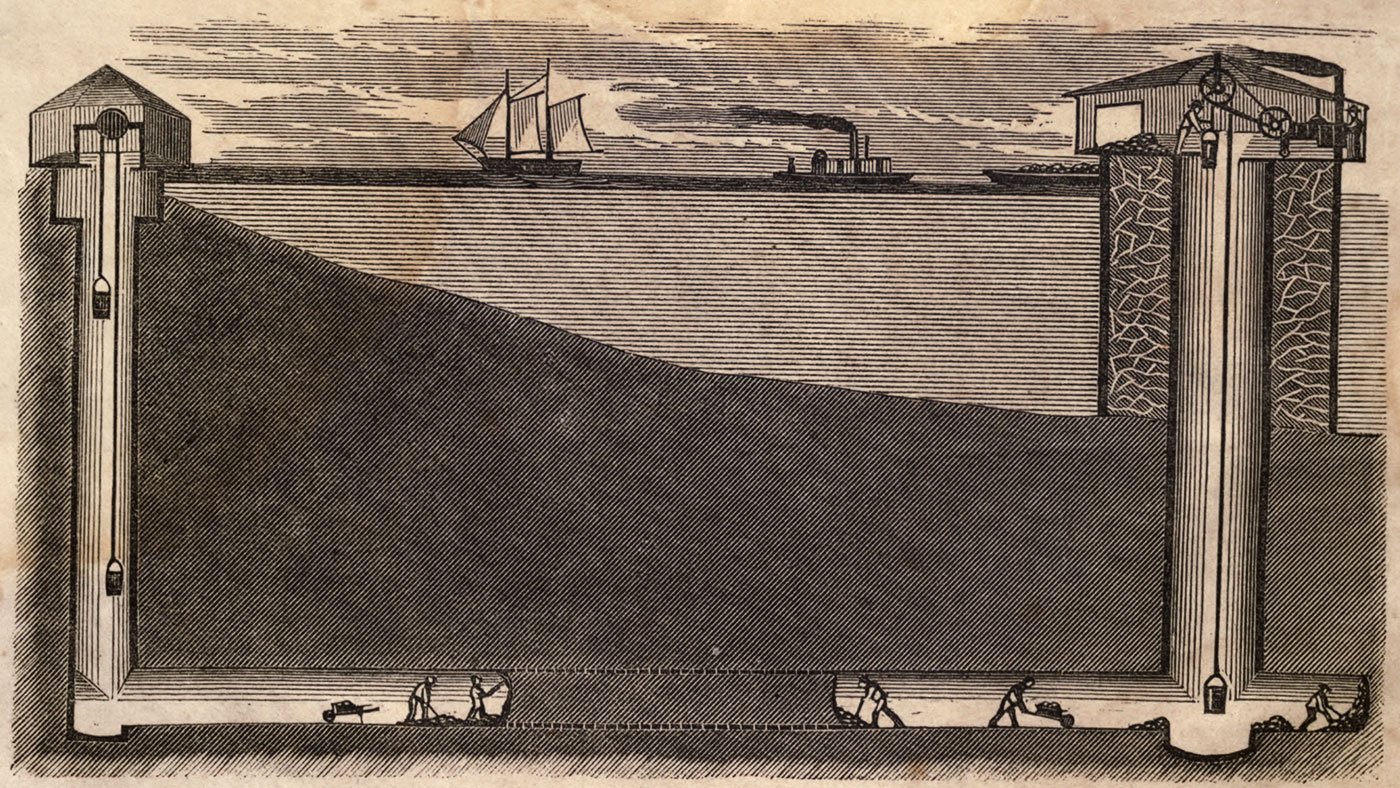

So Chesbrough devised a new plan based on what he had observed in many European cities: they would move the water intake further out into the lake. At the time, the city was getting its fresh water just off shore. If they could instead dig a long underground tunnel and move the intake nearly two miles into the lake, the drinking water might be out of the reach of the city’s filth.

It was one of the most fantastic and adventuresome engineering projects of the era. Workers began digging in 1864. Eventually there were two teams – one digging from the shore and one from the new intake crib.

“It was like a precision army working under Lake Michigan in this brick tunnel,” said Samuelson, explaining that they used picks, shovels, and mule-drawn carts to haul the dirt and rocks out from beneath the lake. “And it had to be done in perfect synchronization because you didn’t have a lot of room to maneuver and to have things build up. So it was…this amazing ballet.”

They met in the middle, 60 feet below the bottom of the lake, in 1866. They were fewer than seven inches out of alignment.

And after all that, it still wasn’t good enough. All it took was a heavy rain for the dirty, stinky river water from the growing metropolis to reach the intake.

But Chesbrough had one more ambitious idea up his sleeve. It was his boldest yet: reverse the direction of the Chicago River, sending the city’s sewage away from Lake Michigan and instead towards the Mississippi.

Just west of Chicago is a subcontinental divide. If they could only dig a ditch, or a canal, through that divide, making it deeper than both the river and the lake, then gravity would do the hard work and carry Chicago’s contaminated water in the other direction, away from the Great Lakes.

At first, they tried to deepen the pre-existing Illinois and Michigan Canal. But that didn’t quite do the trick. So they had to dig a bigger and deeper canal.

“What they’re setting themselves up for is a public works earth-moving project that had never been exceeded anywhere,” said Samuelson.

It would be six times deeper than the Erie Canal and four times as wide, cost millions of dollars, and take years of hard work. But it would solve Chicago’s water contamination problem once and for all – no matter how populated the city got and how polluted its river became.

To some, the proposal was seen as wildly impractical, a fool’s errand. To others, it was a looming environmental disaster that would doom downstream communities.

But many believed that – although ambitious, bold, and a potential disaster – it was the best hope for Chicago’s future.

“This was men, machinery, creativity, and pure chutzpah,” said Samuelson.

Unfortunately, it took some time for the massive undertaking to get underway. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 temporarily exhausted city and state coffers.

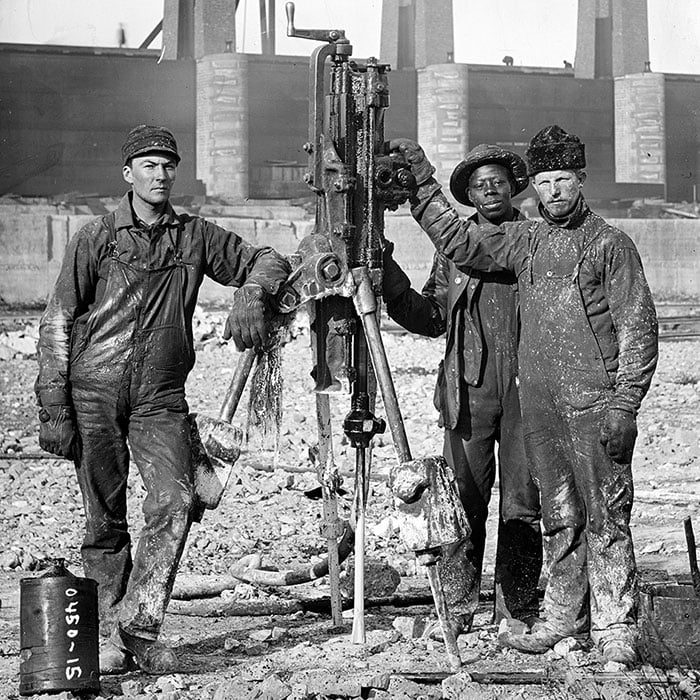

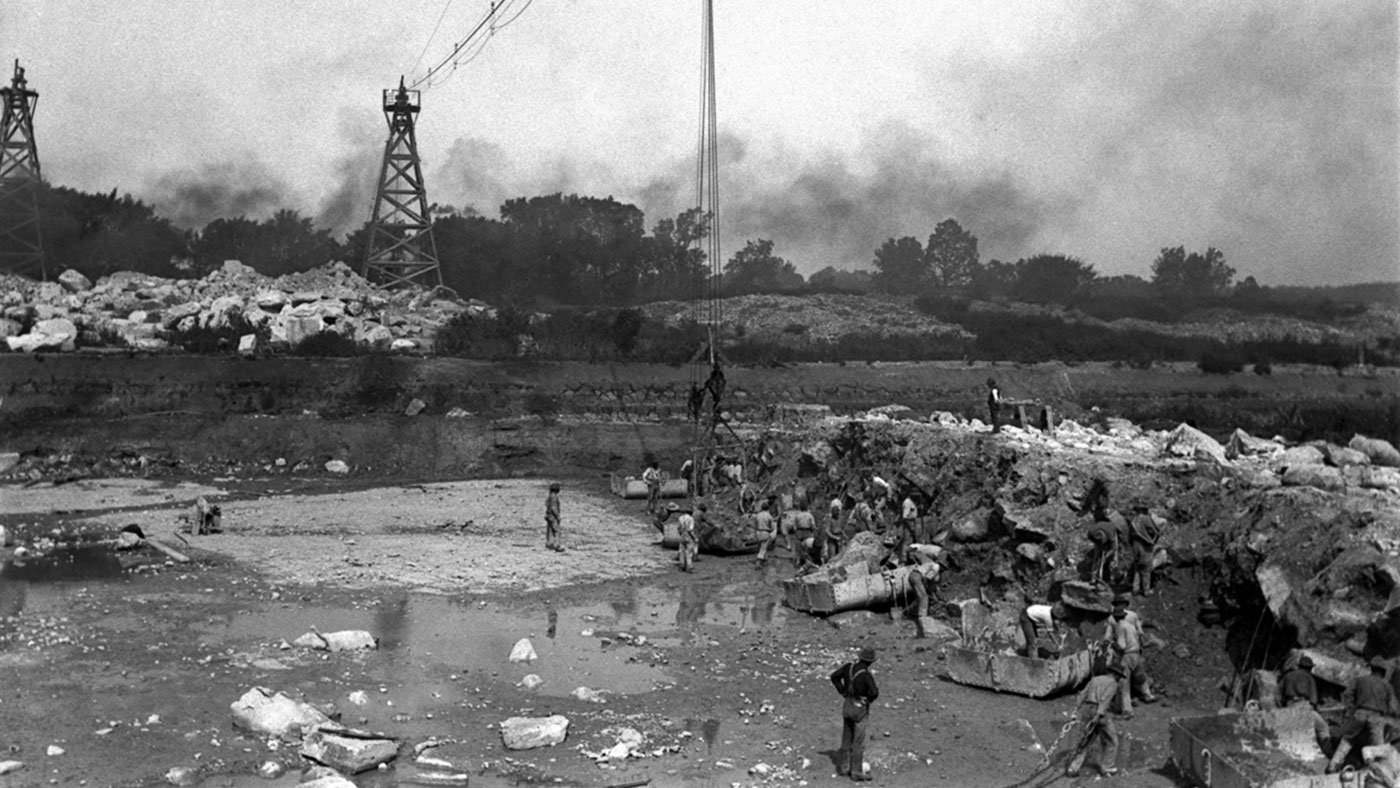

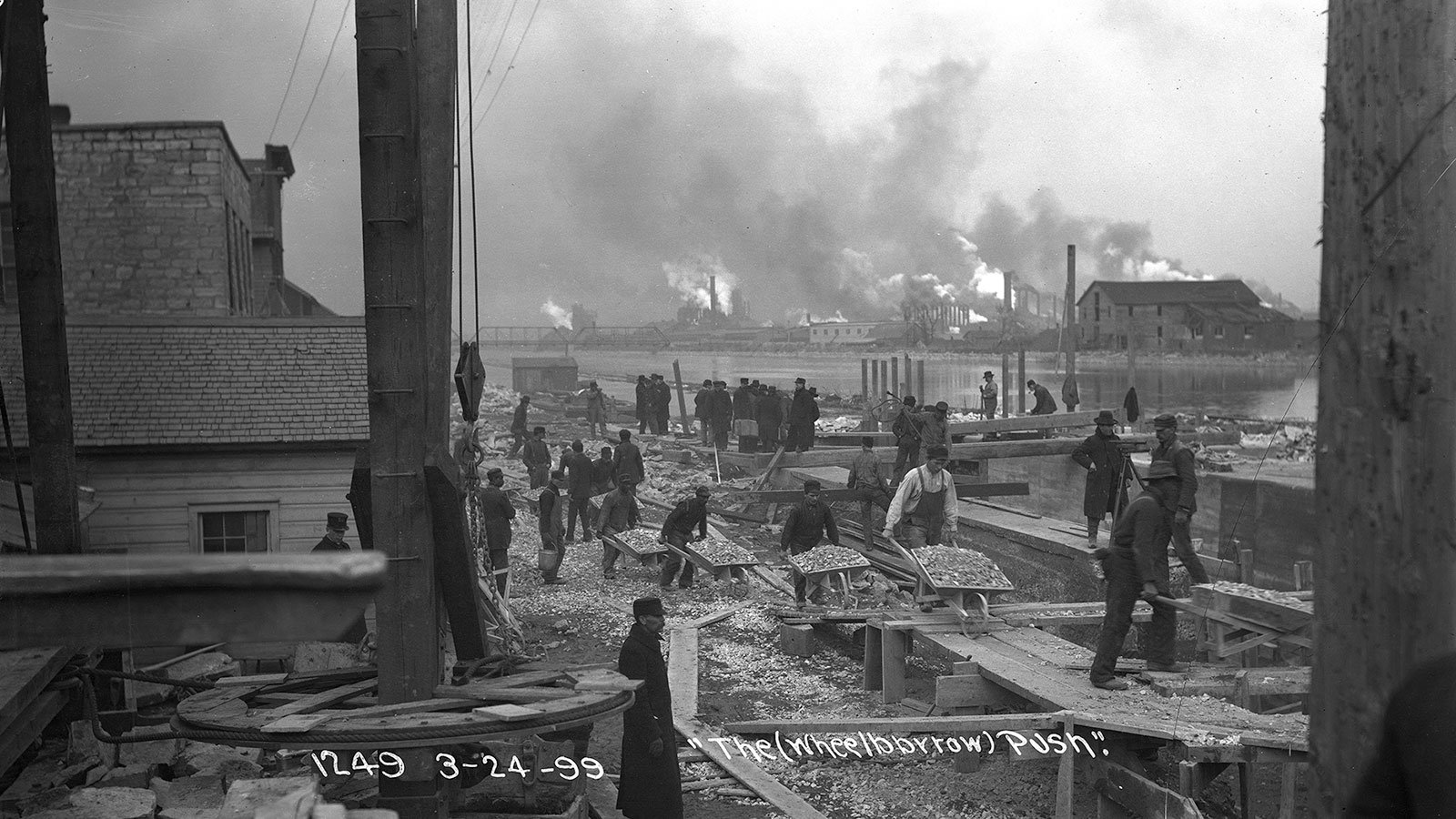

But in 1892, six years after Chesbrough’s death, Chicago finally got to work. Thousands of laborers started digging.

“A lot of it was hard, back-breaking work, basically shovels, horses, wagons, carts, and pulleys,” said Samuelson. “But as time went on, they actually refined the way to do this.”

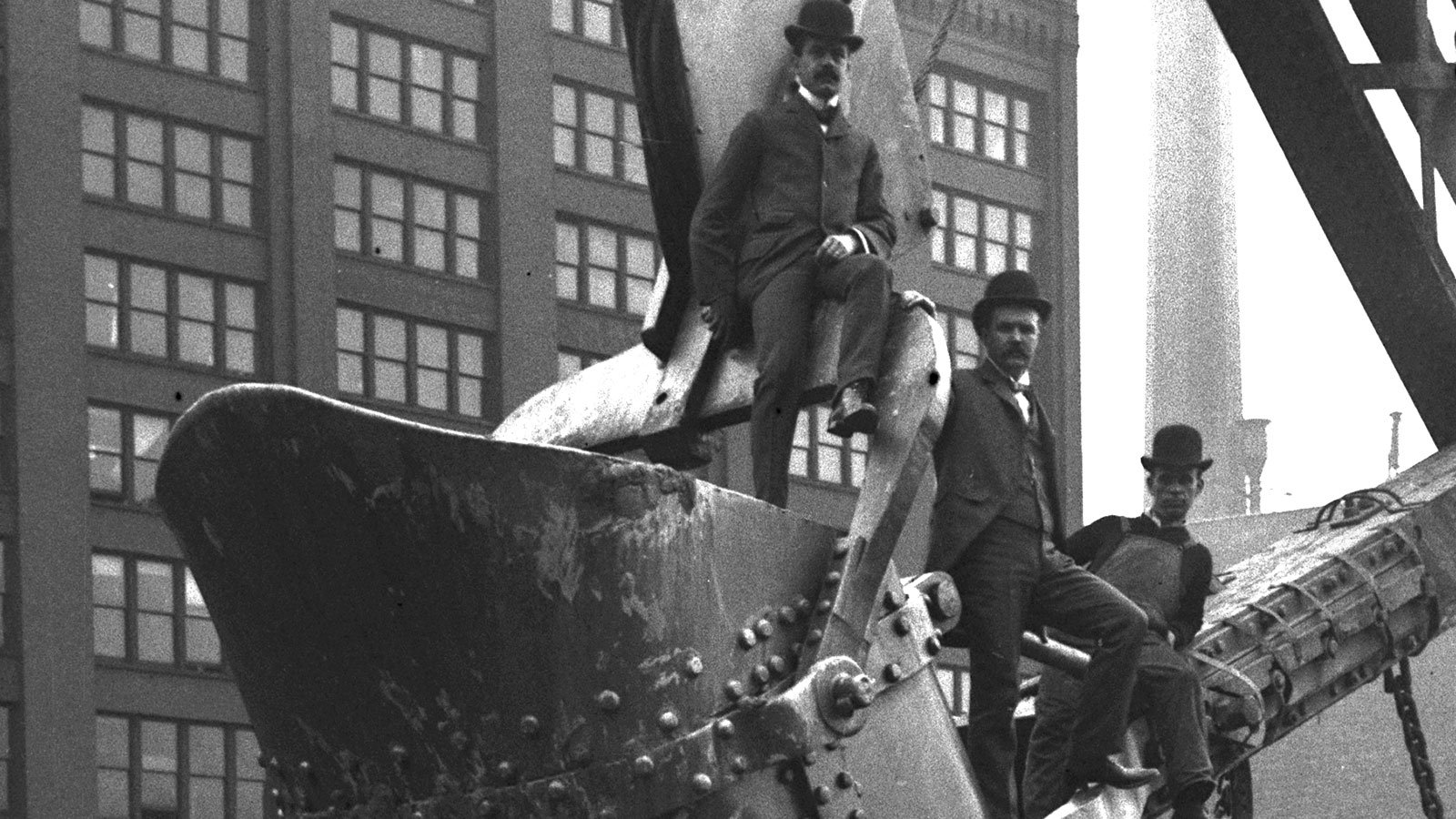

They used dynamite and newfangled inventions like steam shovels and hydraulic suction dredges.

Samuelson says that they even invented new tools and techniques for the job, such as cable cars with large metal towers on each side of the canal. “They’d run a cable in between with a big scoop that could travel on it. So it would then drop down, get the loose material, take it on land, haul it away. This was a big deal…So as you dug more, you could move those giant towers along and keep scooping out that fill, [and] get rid of it.”

“People called this the ‘Chicago style of earth moving,’” said Samuelson. “In many ways, it’s kind of in the good spirit of Chicago. They improvised and figured it out as they went along. [If t]here was a job to [be done], you figure[d] out how to do it.”

In the end, they excavated 42 million cubic yards of rock and soil, or enough to fill the Willis (formerly Sears) Tower twenty times.

They connected the canal to the Des Plaines River, which sent the wastewater down the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico – which didn’t sit well with some of Chicago’s neighbors, particularly in St. Louis, where city leaders began exploring legal options.

But Chicagoans argued that “the solution to pollution is dilution.” In other words, the purifying powers of Lake Michigan would make their stinky, filthy water cleaner.

But St. Louis wasn’t buying it. As the City of St. Louis got to work on a lawsuit to halt the project, Chicago raced to finish the final section of the canal.

On the wee hours of January 2, 1900, canal commissioners undertook a secret mission. Accompanied by select friends, wives, and a few reporters who caught wind of their plans, they set out in the early morning hours to strike the final blow to the last dam holding back the water.

After a few unsuccessful attempts, they finally broke open the dam. According to the Chicago Daily News, Sanitary District President William Boldenweck, who lost both of his parents to a cholera epidemic decades before, cried “Let ‘er go.” The paper called it “the nearest approach to formality of the entire occasion.”

A few days later, according to the Chicago Record, “Water [in the Chicago River] that was actually blue in color and had blocks of ice of a transparent green hue floating in it…caused people who crossed bridges over the Chicago River…to stop and stare in amazement.”

St. Louis filed an injunction against the reversal on January 17.

The issue, as part of a case filed by the State of Missouri, eventually made it to the Supreme Court, which decided in Chicago’s favor. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote that the Mississippi was, indeed, foul – but the putrid waters couldn’t be blamed entirely on Chicago, since several other cities much closer to St. Louis were also discharging their waste into the river. Meanwhile, wrote Holmes, municipalities closer to Chicago were actually benefiting from the infusion of the fresh lake water into their rivers.

The analysis wasn’t entirely accurate. As Libby Hill wrote in her book, The Chicago River: A Natural and Unnatural History, biologists from the Illinois Natural History Survey documented conditions a decade later along the Illinois River in Morris, Illinois, approximately 60 miles southwest of Chicago. There they found “The water…was grayish and sloppy, with foul, privy odors distinguishable in hot weather…Putrescent masses of soft, graying, or blackish, slimy matter, loosely held together by threads of fungi…were floating down the stream.”

Meanwhile, neighboring states along the Great Lakes grew concerned about the diversion of Lake Michigan water to the Mississippi River and eventually to the Gulf of Mexico. This time, the Supreme Court ruled that those concerns were warranted and ordered locks and gates to be installed to help control the diversion of the fresh lake water. Today, even with the locks installed, the reversed river continues to divert an estimated 23,000 gallons of precious fresh water toward the Mississippi, and the ocean, every second.

And there were other unforeseen consequences. The canal has become a highway for invasive species such as zebra mussels.

As Chicago’s population has grown and its water treatment practices have improved, conversations have reopened about how the river might continue to be engineered and whether it ought to be restored to its natural course. There are significant environmental and engineering challenges to reversing course at this point.

But, says Samuelson, “Chicago has been good solving these sorts of things before…If it needs to be done, they’ll figure out a way to do it.”

![welfth St. Vascule [i.e. Bascule] Bridge, Chicago](http://interactive.wttw.com/sites/default/files/Marvels_5_ChiRiver_VasculeBridge_LOC.jpg)