Transcontinental Railroad

Transcontinental Railroad

Discover the complex negotiations that went into the creation of the railroad that would shrink the time it took to cross the nation from six months to one week.

In the early nineteenth century, traveling from the East to the West Coast was a four- to six-month journey, and safe passage was far from guaranteed. The land routes took travelers through deserts, across plains and rivers, and over mountains. Sea passage took just as long, taking travelers either through Panama or around Cape Horn, on South America’s southern tip.

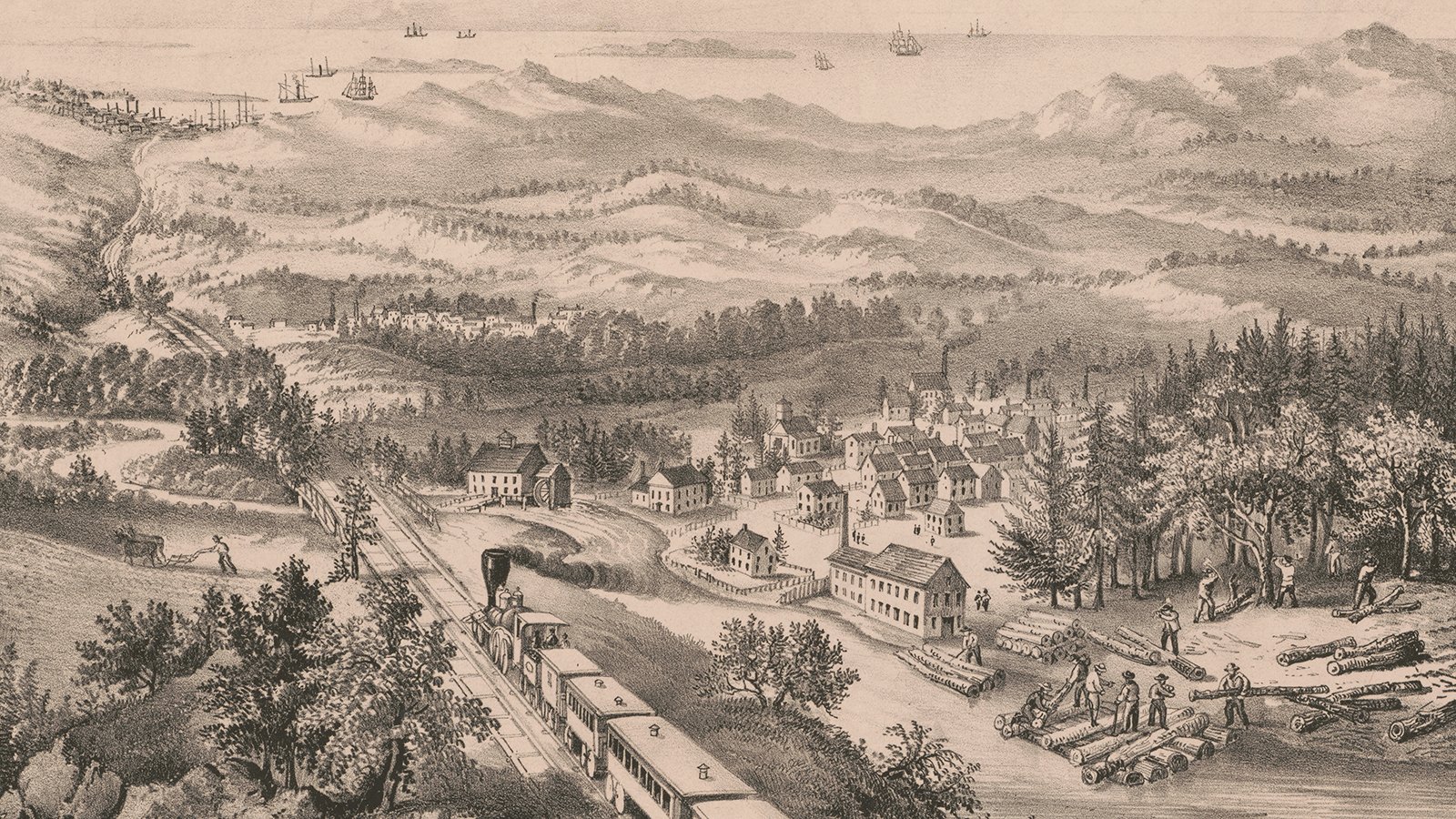

The construction of the Transcontinental Railroad would drastically change that, directly connecting the coasts, making travel cheaper, quicker, and safer and opening the door for massive economic expansion across the country.

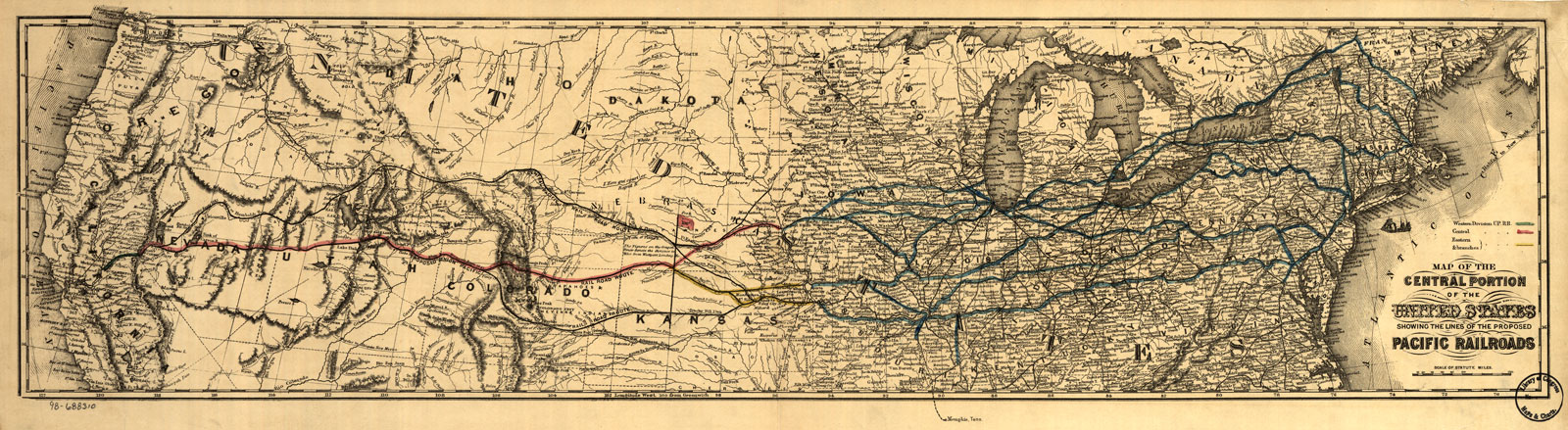

By the mid-nineteenth century, most everyone in Washington agreed that America needed a railroad to connect the coasts. By 1848, five separate railroad resolutions went before Congress, each proposing a distinct route, most of them snaking through the lower passes on the northern side of Rocky Mountains, headed towards San Francisco or Vancouver, or traveling south towards San Diego, avoiding the Rockies and the Sierra Nevada altogether.

The debate surrounding the railway’s path became particularly charged in the years immediately preceding the Civil War.

“The Southern legislators would not let a northern route go in because it would give the North supremacy,” said Phil Sexton, a cultural and national heritage interpreter with the California State Railroad Museum. “The Northern legislators would not allow a southern route because it could help expand slavery.”

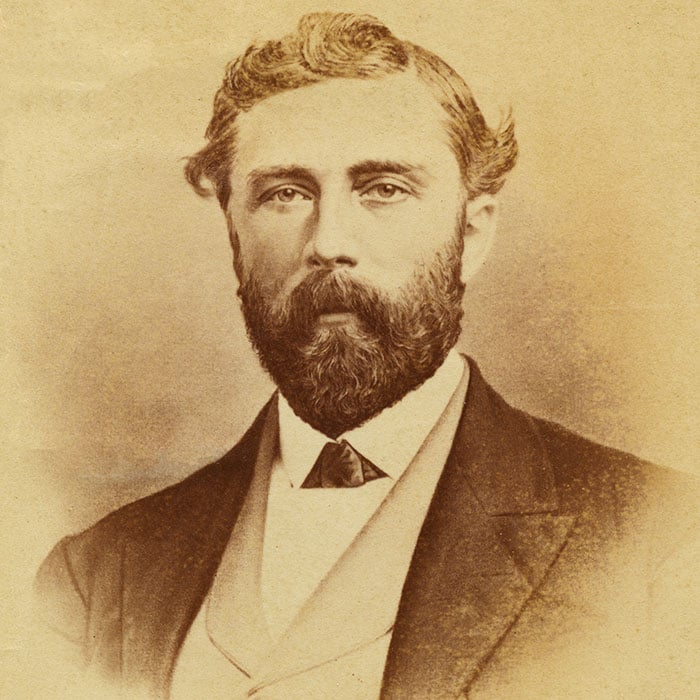

But California engineer Theodore Judah, who had already overseen the construction of the first rail line west of the Missouri River, scouted out and surveyed a third option with the backing of four Sacramento merchants and gold rush tycoons known as the “Big Four.” Judah’s proposed path ran straight through the snowy Sierra Nevada mountains to Sacramento, California, the heart of the California Gold Rush.

In 1857, Judah published and distributed copies of a pamphlet laying out his vision and his research. A Practical Plan for Building the Pacific Railroad drummed up significant interest in Washington and drew more financial backers to his cause.

Still, many thought his route was preposterous. Though more direct, it would be much more difficult to build.

But soon after the Civil War broke out, Judah headed back to Washington to lobby once again. Only now, with the Southern legislators removed from the voting pool, Judah had much less opposition. He and his supporters in Washington were also able to sell the cross-continental line as a war measure, designed to link California and Nevada – and their rich resources – more closely to the Union.

The Pacific Railroad Act, which Judah helped write, was signed by President Lincoln on July 1, 1862. It authorized the Union Pacific to build westward from Council Bluffs, Iowa, while the Central Pacific built eastward from Sacramento, California. The two tracks would then meet at a point to be determined. In Iowa, trains would connect to and from the Atlantic coast on existing railroads, thus creating a coast-to-coast route.

However, though the federal support won Judah loans, grants, and permission to start construction, getting the project off the ground remained a challenge, particularly for the Central Pacific.

First, the equipment they needed was stuck on the East Coast. Nearly every spike, rail, shovel, and locomotive had to be sent via ships that sailed south around Cape Horn and up the Pacific Coast.

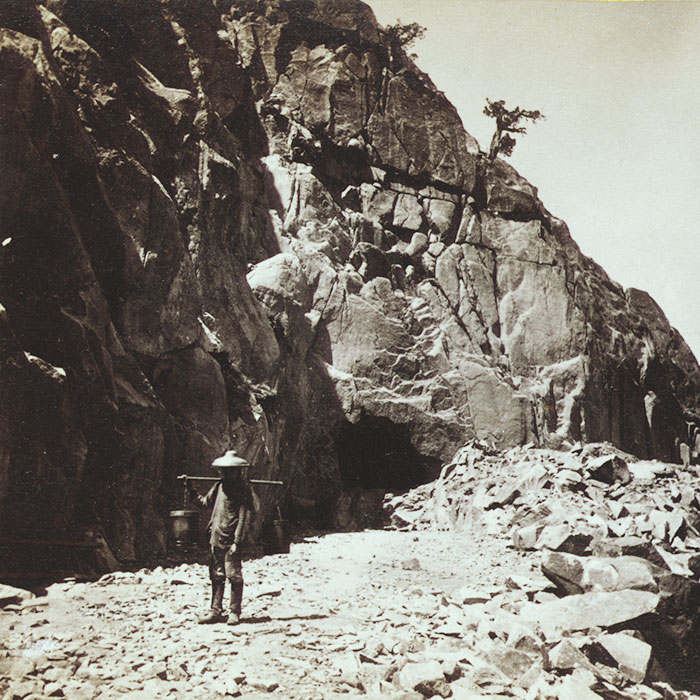

An even more daunting challenge was to recruit enough labor for the herculean task. Initial enlistment efforts fell far short of the number of workers needed for the job, so foremen turned to Chinese laborers. Initially, they recruited migrants who had come to California during the Gold Rush. When that wasn’t enough, they recruited directly from impoverished regions of China. Though records differ, historians agree that at least 10,000 Chinese laborers were employed by Central Pacific at the time, representing nearly 90 percent of the workforce.

“The conventional wisdom is that Chinese laborers were unskilled, illiterate, but actually they were skilled,” said Sue Lee, former head of the Chinese Historical Society of America. “They came from the Guangdong area…and they had all kinds of skills. They were miners, they were stone workers,…they were carpenters, as well as doctors.”

The Chinese laborers often did the most arduous, death-defying jobs and worked 12-hour shifts. After fees for housing and travel were deducted, they also earned far less than their white, mostly Irish, counterparts.

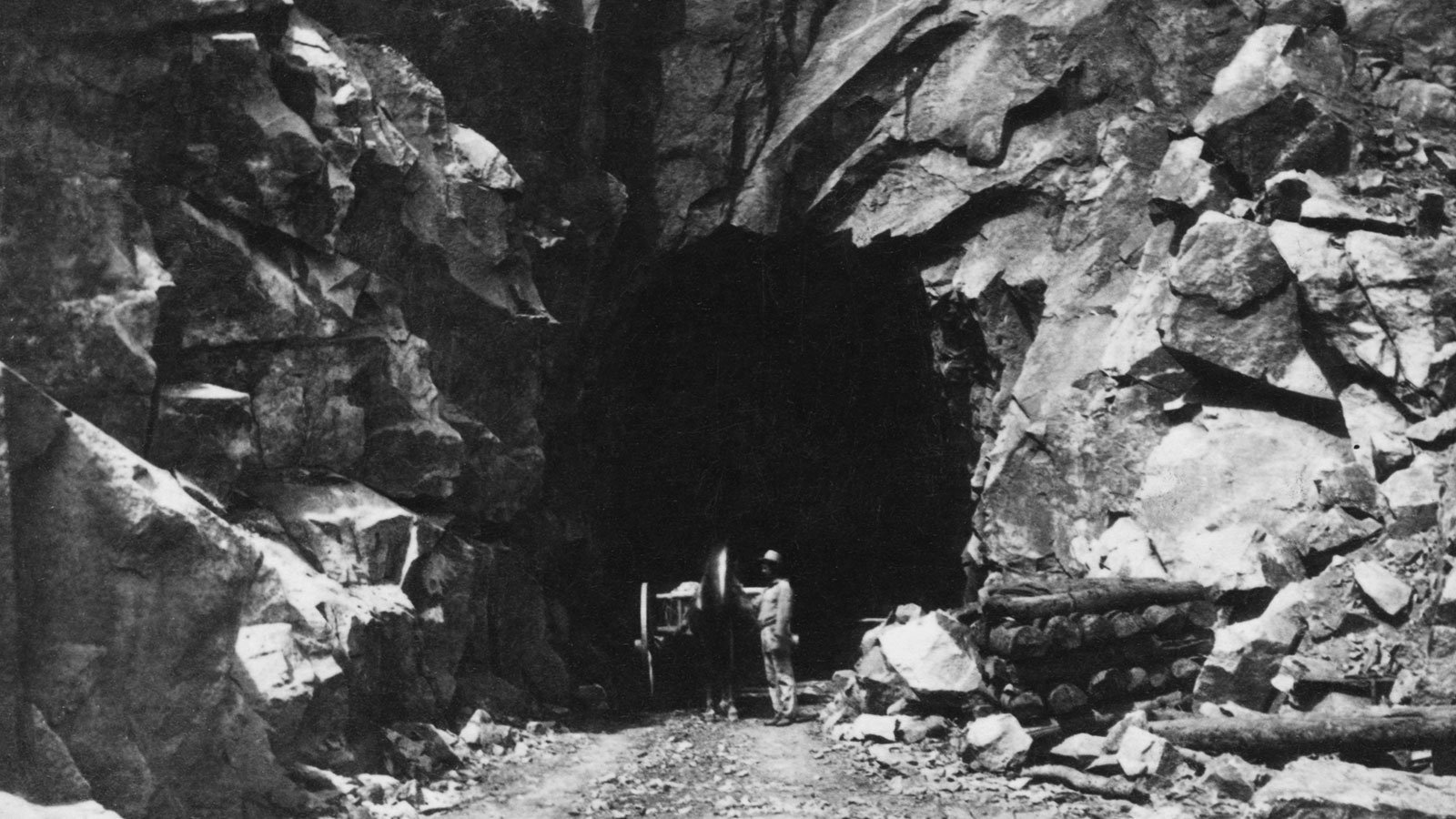

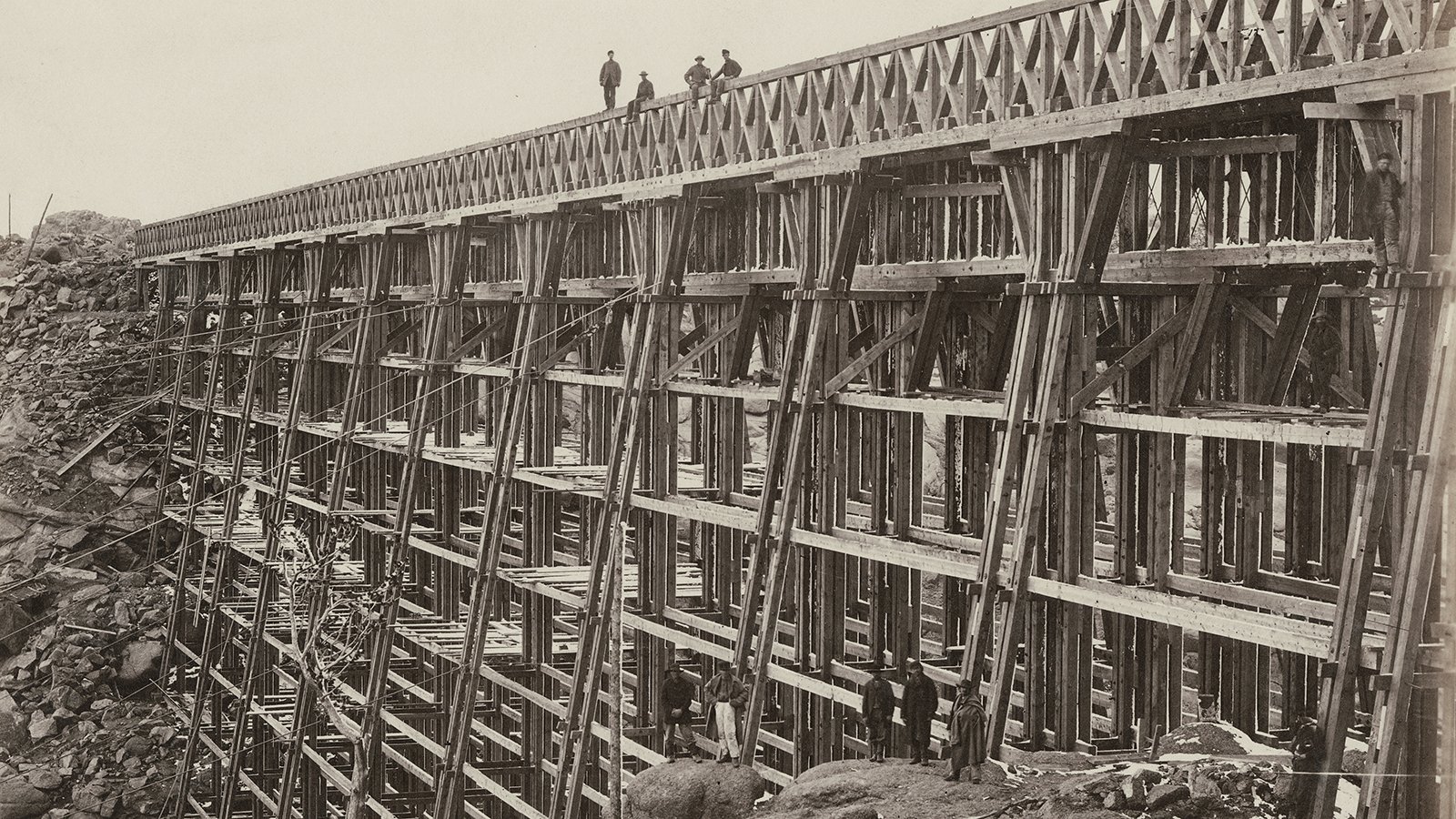

In some spots, workers built wooden trestles to cross deep ravines. In other places, they carved shelves into mountainsides. But high up in the mountains, they often had to dig tunnels, many of them through solid granite. To do that, they used highly volatile nitroglycerin.

One of the most difficult portions of the track ran through Donner Pass, which became the stuff of legend and childhood nightmares just decades prior, when a group of 81 pioneers became trapped there for the winter, and some resorted to cannibalism to survive. The Summit Tunnel through Donner Pass was the longest at nearly 1,700 feet. Workers expedited the job by blasting a vertical shaft and then excavating out from the middle while others tunneled from both ends.

It is unknown how many Chinese died in the process. Estimates range from 50 to 1,200 fatalities.

“But it’s not documented, which is very sad,” said Lee. “Without the Chinese labor, the Transcontinental Railroad…would have taken several years more. It really was the diligence and teamwork of the Chinese that helped finish the railroad.”

As it was, only six years after construction began, the eastern and western rail lines met at Promontory Summit, Utah, on May 10, 1869.

Sadly, despite the relatively quick work, Theodore Judah wasn’t there to see the realization of his long-cherished dream. Disagreements between Judah and his business associates in 1863 left him with the option of either selling his shares to his partners or buying them out. He traveled to New York via steamer to seek financial support but contracted yellow fever while docked in Panama. At the age of 37, Theodore Judah died shortly after his arrival on the East Coast.

Amtrak still operates passenger trains over portions of the original Transcontinental Railroad route. Even today, navigating that treacherous path can present challenges for engineers.

In the end, Judah's partners – Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker, Mark Hopkins, and Leland Stanford, known as the “Big Four” – reaped the rewards of the project that he set in motion.

America changed almost overnight. The Transcontinental Railroad allowed for goods to be shipped and sold nationally and laid the foundation for America’s global economic ascendance. It also stitched together a collection of far-flung states into a single country, allowing people and ideas to travel more widely than ever before.

“The railroad gets completed and suddenly everybody knows everybody all over the country,” said Sexton. “It speaks to the passion and drive that people had to span this continent and to really make this a transcontinental nation.”