Bunker Hill Monument

Bunker Hill Monument

One of America’s earliest monuments by architect Robert Mills, this towering obelisk honors not one “great hero” but the heroism of all who fought in the Revolutionary War, a democratic monument for a new democracy.

The giant, granite obelisk that soars above the city of Boston isn’t the oldest monument in the United States. It isn’t the tallest, the most technically impressive, or the most frequently visited.

But the Bunker Hill Monument was pivotal in helping the citizens of the young United States of America forge a shared identity, celebrate a common history, and honor those who died in the first major battle in the Revolutionary War.

Today, this 221-foot monument stands in the heart of Boston’s trendy Charlestown neighborhood, a waterfront community situated between the Mystic and the Charles rivers, overlooking Boston’s North End. When the weather is nice, locals flock to the surrounding lawn to play Frisbee, soak up the sun, and walk their dogs.

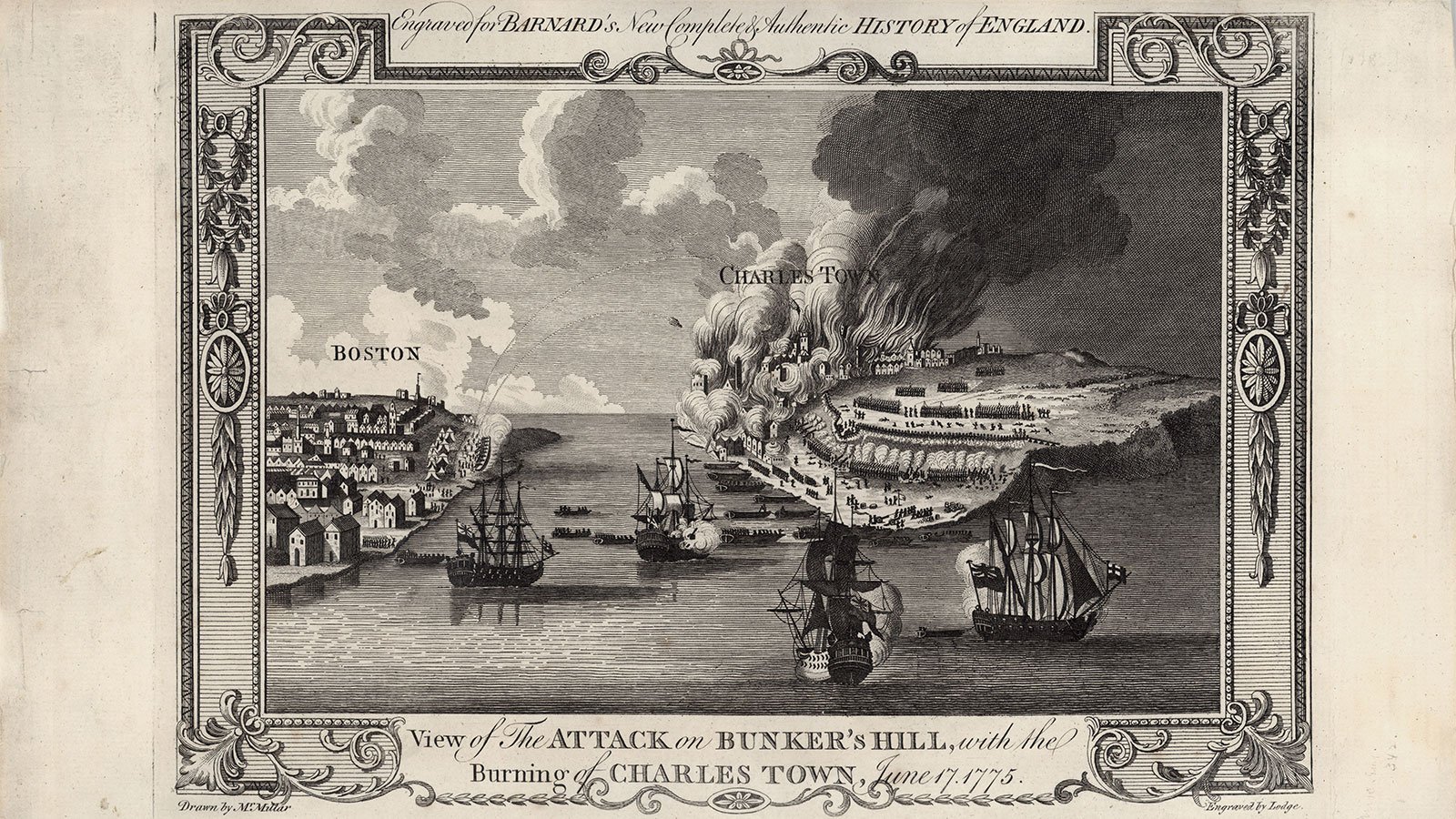

But on a sunny day in June 1775, this same patch of ground witnessed devastating bloodshed.

The first clashes between colonial militias and British troops at Lexington and Concord happened just two months prior – but they were mere skirmishes. The quiet that followed those confrontations left the world wondering whether the ill-equipped and decentralized American rebels were truly willing to challenge the powerful British Army in an all-out war.

Following Lexington and Concord, British troops retreated to Boston, which was then surrounded by British naval vessels. Meanwhile, as word of the rebellion spread, militia men flocked to the city and its environs from throughout the northern colonies, eager for a showdown.

In mid-June, American Commander General Artemas Ward instructed his soldiers to fortify Bunker Hill, which provided both a clear view of Boston and a strategic location from which to launch artillery fire. But, for reasons still uncertain, the soldiers opted instead to build their redoubt, or earthen fort, slightly lower and closer to the waterfront, on Breed’s Hill.

The rebels worked through the night of June 16, 1775. The British couldn’t see them from across the harbor, but they could hear their picks and shovels. As dawn broke, British soldiers spotted the redoubt and took it for what it was – a provocation.

British generals began planning an attack and organizing their troops, the first of which arrived at the Charlestown docks in the early afternoon. They were well equipped, well trained, and well rested. They marched confidently uphill.

Legend has it that, with limited resources and less powerful muskets, a senior officer instructed the rebels to hold their fire until they saw “the whites” of their enemies’ eyes. Historians have since questioned that detail. No one, however, has questioned the fact that the colonists were far outgunned.

Still, when the British trudged uphill, they were completely exposed. And when they came into range, the rebels fired, causing the British to fall in droves. They retreated downhill and, a short time later, surged again only to meet the same fate. On the third advance, the rebels’ munitions began to dwindle. Some resorted to throwing rocks. As the British soldiers overtook the rampart, the Americans swung their empty muskets as a last defense. Bloody hand-to-hand combat ensued.

“Nothing could be more shocking than the carnage that followed the storming…,” a royal marine later wrote in a letter to his brother. “We tumbled over the dead to get at the living….”

When the smoke cleared, 1,054 British soldiers and 400 Americans lay dead or wounded.

Although the Americans had lost control of their redoubt, the Battle of Bunker Hill, as it incorrectly became known, was a tremendous moral victory for the rebel army. A ragtag band of local militias had managed to inflict heavy losses on the world’s most powerful army.

It was a turning point in the Revolutionary War and in world history.

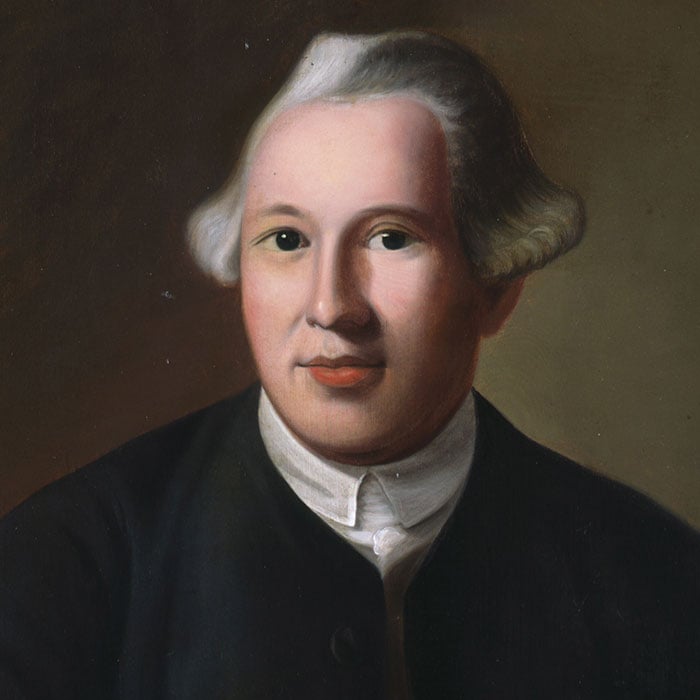

The Americans who died in that battle were soon revered as heroes. Among the casualties on the American side was Major General Joseph Warren, a well-known political orator, physician, and rebel leader. Warren’s story of bravery and self-sacrifice for the Revolutionary cause appeared throughout the colonies in newspapers, pamphlets, songs, sermons, and even theater productions. A monument to Joseph Warren – a wooden column topped with a gilt urn – was erected at Breed’s Hill in 1794.

Decades later, as the number of surviving Revolutionary War veterans were dwindling, and the younger generations sought to preserve and honor their stories, an effort arose to create a lasting, universal tribute to all who died in that first, pivotal battle. Three prominent Bostonians formed the Bunker Hill Monument Association in 1823 to preserve the battle site and create a monument that would convey the significance of the battle to future generations.

The association selected an obelisk designed by architect Robert Mills as the centerpiece of their memorial. Traditionally used in Egypt to mark the graves of fallen heroes, obelisks were gaining popularity in America. In the eyes of many, the obelisk provided an alternative to traditional war monuments featuring a single leader. Instead, it offered a more democratic monument for a new democratic nation.

On June 17, 1825, on the fiftieth anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill, an estimated 150,000 people came from near and far to celebrate the dedication of the site and the laying of the monument’s cornerstone. Reporters from throughout the country converged in Boston to document the young republic’s first massive public display of national pride.

A formal procession through Boston included between 40 and 60 veterans of the Battle of Bunker Hill, in addition to more than 100 veterans of the Revolutionary War and the Marquis de Lafayette, a French military officer who fought in the American Revolutionary War and was a close friend to several founding fathers. A witness wrote that during the procession “All the streets, the houses to their roofs, and in some instances to chimney-tops, and every situation on which a footing could be obtained for a prospect of the procession, were filled with a condensed mass of well dressed, cheerful looking persons, of all sexes and denominations, many of whom had occupied their stations for several hours; and who, at appropriate places, spontaneously rent the air with joyous and orderly acclamations.”

After the cornerstone was laid, prayers were said, and dinner, punctuated with lengthy toasts, rousing applause, and music, was served to 4,000 on the old battlefield site.

Despite the enthusiastic launch event, it would take another twenty-four years to complete the monument. First, there were technical obstacles. Transferring 6,700 tons of granite from a nearby quarry required the construction of a special horse-powered railroad.

Then there was funding. The memorial was bankrolled almost entirely by private donations, which came in fits and starts through efforts organized by several groups and individuals over time. In the end it was Sarah Josepha Hale, a magazine editor, author, and the daughter of a Revolutionary War veteran, who raised the final $30,000 needed through a ten-day women’s fair in Boston.

Workers completed construction in 1842.

Today, visitors from around the world are drawn to the monument. School children, scholars, foreign tourists, and others come to learn about the battle. The hearty among them climb all the way to the top of the monument to take in the view. And they all pay their respects to the men who challenged the British Empire, initiating the war that would give birth to a new nation.