Mount Rushmore National Memorial

Mount Rushmore National Memorial

Designed as a tourist attraction, Mount Rushmore celebrated America’s expansion west; now, 70 years in the making, a new memorial to Native American leader Crazy Horse completes the state’s salute to its history.

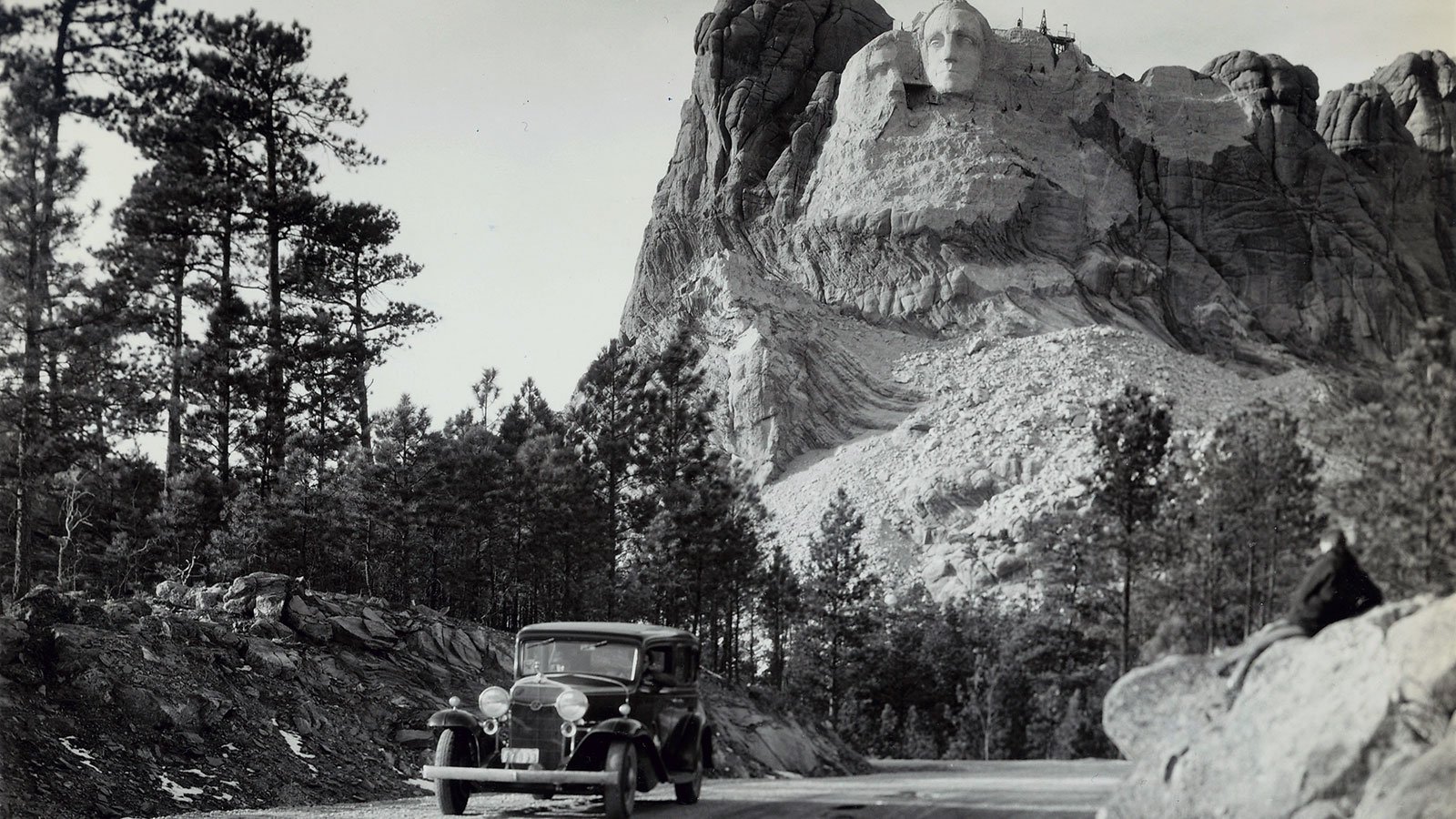

The bold idea to carve giant, three-story-tall faces out of the granite of the Black Hills came not from an impulse to commemorate an important event or mark a historic battlefield. It was driven by a burning desire during the ascent of the popularity of the automobile to draw tourists to an out-of-the-way corner of an out-of-the-way state: South Dakota.

Soon after the invention of the Model T in 1908, local boosters throughout the country began pushing for the construction of highways and other infrastructure in an effort to lure early American adventure seekers to their towns.

South Dakota’s historian Doane Robinson was among them and was particularly ambitious in his vision. South Dakota, which had become a state only some 30 years prior, is full of beautiful scenery. But Robinson feared that gorgeous vistas wouldn’t be enough to draw tourists to his state en masse. He needed a gimmick – a roadside attraction that could draw travelers from near and far.

Flipping through the newspaper one day, he found his inspiration. On a mountain outside of Atlanta, Georgia, the Daughters of the Confederacy had hired artist John Gutzom de la Mothe Borglum to carve a larger-than-life monument to Confederate heroes. But the strong-willed artist was embroiled in a series of disagreements with his employers.

Robinson reached out to Borglum and pitched his idea, and Borglum traveled to South Dakota to explore it.

Robinson took him on a tour of the Black Hills and explained his concept: to carve heroes of the American West – including George Custer, “Buffalo Bill” Cody, and Lewis and Clark – into tall, thin, granite rock formations in the Black Hills, known as “The Needles.”

But Borglum didn’t see it. It would be difficult to carve faces into the freestanding granite, he told Robinson. Besides, his son Lincoln later wrote, the faces would “look like misplaced totem poles.”

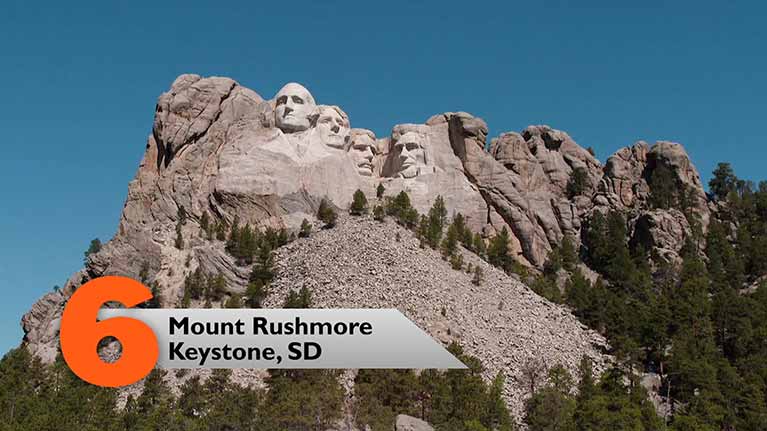

Borglum continued brainstorming and ultimately chose the southeast face of Mount Rushmore, named after an attorney who assessed mining claims in the area in the 1880s. With an unencumbered view from various points in the Black Hills, the 450-foot-high mountainside would make the perfect canvas for his project.

Borglum also challenged Robinson’s concept of featuring Western heroes in the stone.

“I want to create a monument so inspiring that people from all over America will be drawn to come and look and go home better citizens,” he said in 1927. And so he proposed featuring former presidents who he believed could represent the “foundation, preservation, and expansion of the United States.” To do that, he would chisel the likenesses of George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Abraham Lincoln, and Teddy Roosevelt on the side of the mountain.

The inclusion of Roosevelt, a personal friend of Borglum’s, initially raised eyebrows. But the sculptor was relentless, and eventually, Robinson and others conceded.

By 1929, Borglum also managed to rally support – and funding – in Washington. Congress approved federal matching funds for up to $250,000, or half of the estimated cost of the memorial.

But where Borglum saw a perfect carving block, Native Americans saw hallowed ground.

Many local Lakota see the carving of four white men into the side of their sacred land as just another insult in a long history of broken promises and injustices.

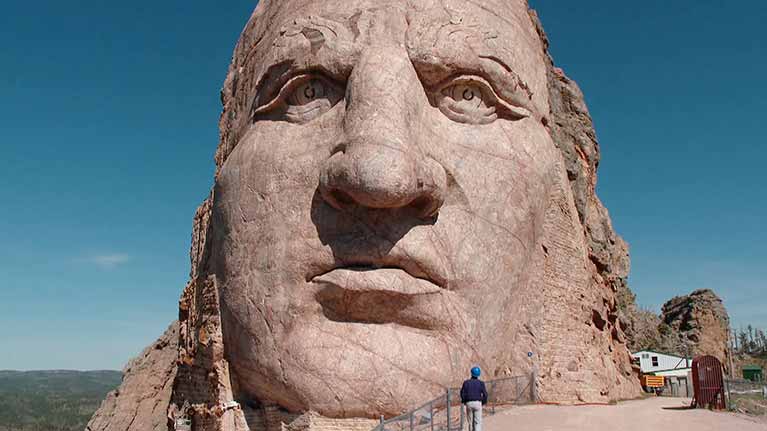

Lula Red Cloud, great-great-granddaughter of Oglala Lakota Chief Red Cloud, explains what she sees as the relevance of honoring Lakota warrior Crazy Horse with a larger-than-life monument in the Black Hills of South Dakota.

The United States declared the Black Hills to be Lakota land in the 1868 Treaty of Fort Laramie. But just a decade later, after gold was discovered in the Black Hills, U.S. authorities changed their minds. They fought for ownership of the Black Hills in the Great Sioux War of 1876, forcing the Lakota to surrender the Black Hills to the U.S. government the following year.

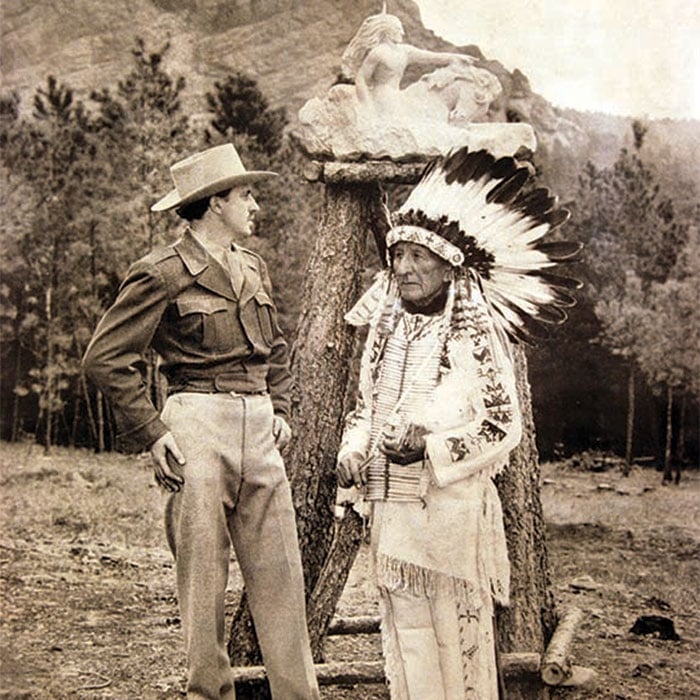

Soon after Borglum’s men began carving the side of Mount Rushmore, Lakota Chief Henry Standing Bear hired his own artist to carve an even bigger monument to the legendary Lakota leader Chief Crazy Horse. That project continues to this day, funded entirely by private citizens, on a cliff just 15 miles from Mount Rushmore.

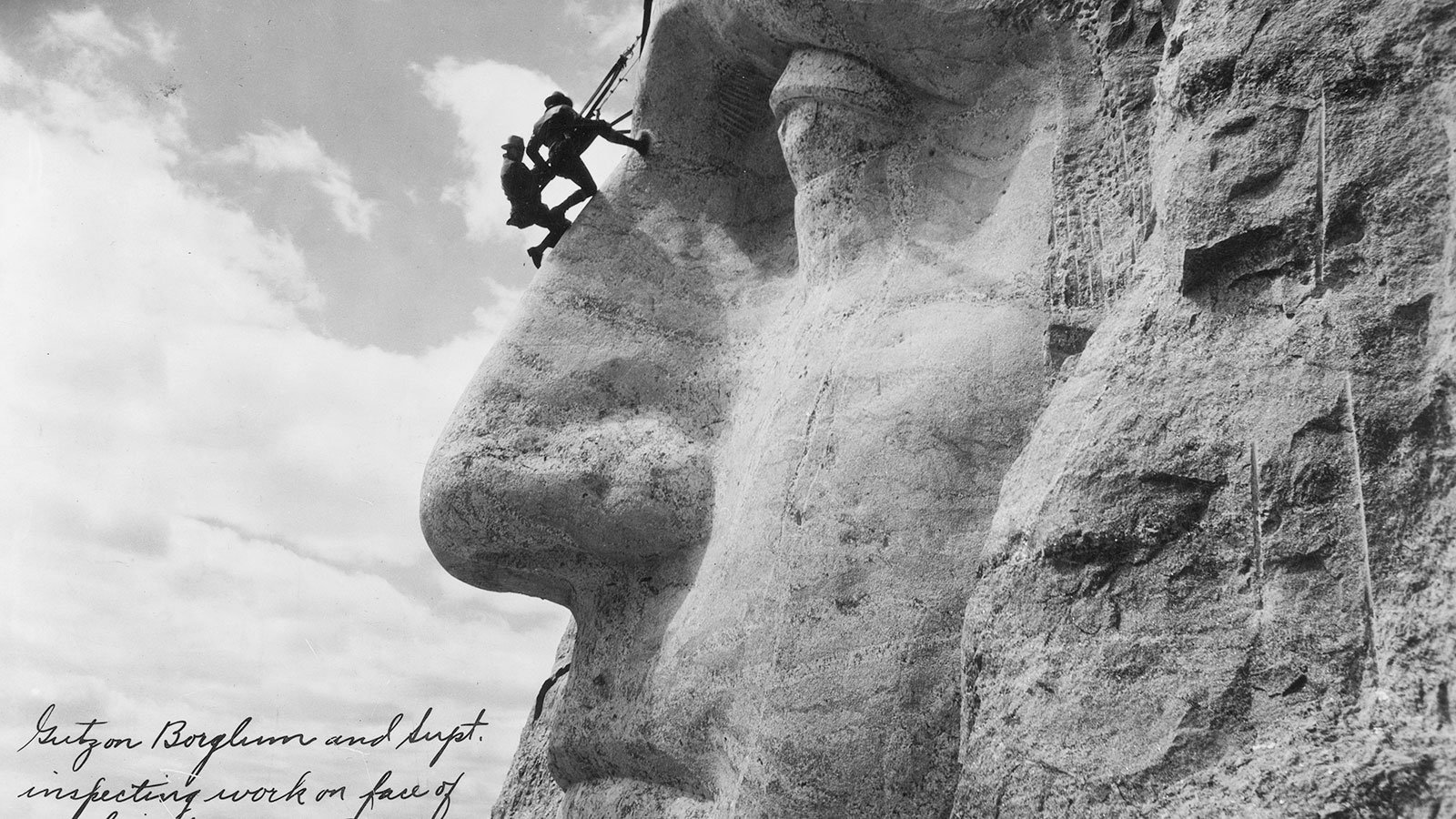

Meanwhile, it took fourteen years for approximately 400 workers to blast several tons of granite from the side of Mount Rushmore. The final sculpture was much different than Borglum originally envisioned. A combination of depleted funds, cracked granite, and overly ambitious plans required Borglum to change his design and scrap plans to etch a 500-word history of the United States into the stone.

And although Borglum intended to carve the presidents all the way down to their waists and build a hall of records to house the American Constitution and other historically relevant artifacts inside the mountain, he ran out of time. On his way to lobby Congress for additional appropriations in 1941, the sculptor died suddenly after an emergency surgery in Chicago.

After his father’s death, Lincoln Borglum used the project’s remaining $50,000 to complete some detail work and clean up the site. He then declared the project complete.

Today, park rangers include the Lakota perspective – as well as the history of the monument and the artist who created it – in the telling of Mount Rushmore’s history.

And in fulfillment of Doane Robinson’s original vision, the site sees a lot of traffic – cars, tour buses, and motorcycles carry an estimated three million visitors annually to the Black Hills, making it perhaps the most successful roadside attraction in America.