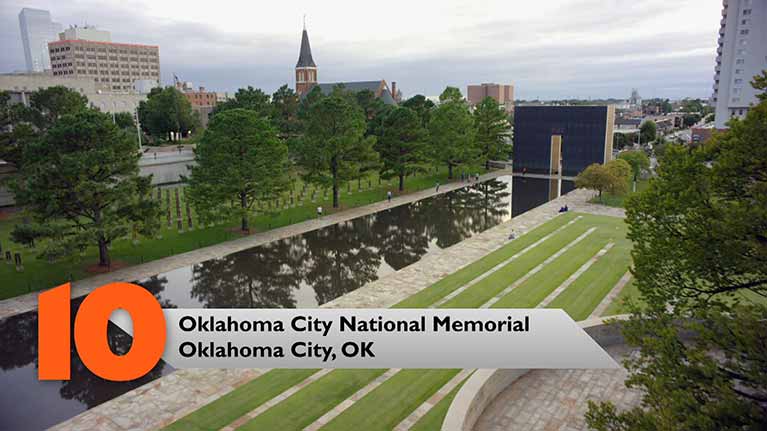

Oklahoma City National Memorial

Oklahoma City National Memorial

The 1995 bombing at the Murrah Federal Building was the deadliest act of terrorism on American soil until 9/11, leaving 168 dead and more than 800 injured. Like the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, Hans and Torrey Butzer’s monument honors the dead – each with a single empty chair.

On the morning of April 19, 1995, Amy Downs started her day with a sense of anticipation. She was young, working at a job with several of her good friends, it was springtime, and she was getting ready to buy her first home. Life was good.

She arrived at the office around 8:00 am and spent about an hour talking with friends.

“I was goofing off, visiting,” she says. “I was...showing them all pictures of the house and everything.”

When nine o’clock rolled around, she decided she should get focused. She walked down the hall and sat down at her desk. She was on the phone when a pregnant co-worker came in and sat down. She hung up and turned to see what she needed.

“That’s when it happened,” she said.

“It” was the deadliest act of domestic terrorism the U.S. had ever seen. A truck packed with explosives had obliterated a large portion of the federal building where she worked, taking the lives of several of her friends and creating a deep schism between her old life and her new reality.

“Everything went dark, and it was just this roaring. It was so loud,” she said. “I felt like I was falling and didn’t realize I was falling for three floors.”

“I found out later I was upside down, still in my chair,” she remembered. “My mouth was full of just rubble. There was this horrible smell. I couldn’t see anything. I couldn’t move, and it was really hard to breathe and it was extremely hot. I remember that. I remember laying there wondering, ‘Am I the only person left alive?’”

The nine-story Murrah Federal Building in downtown Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, had been destroyed, killing 168 people, including 19 children and one rescue worker. Another 800 people were injured.

Amy Downs was one of them. She was buried for six and a half hours until rescue workers managed to pry her from the wreckage. In the days that followed, she sat in a hospital bed and learned that 18 of her 33 co-workers had died, including her best friend, who was mother to two young girls, and the pregnant woman who had just walked into her office.

“Afterwards, dealing with physical injuries was nothing compared to dealing with the grief and the emotion of losing that many people,” she said.

Within hours of the attack, a spontaneous memorial began to take shape on the chain-link fence erected around the rubble. Mounds of flowers, stuffed animals, photos, and prayers were hung there by visitors. It became an immediate touchstone for grieving family members, traumatized rescue workers, and a city shaken to its foundation.

Soon, plans were underway for a permanent memorial with a design that would be dictated by the community itself. Originally, the planning committee was 350 strong, and their decisions were guided by the results of a massive survey of nearly 7,000 people connected in some way to the tragedy.

“In Oklahoma City, we see that the community rallies – the families of those lost, but the entire community, really – comes together to offer their input on what should be built,” said Judith Dupré, architectural historian and author of Monuments: America’s History in Art and Memory.

Eventually, the larger group was distilled into a fifteen-member selection committee, including eight family members and survivors, four design professionals, and three community leaders. Together, they judged more than 600 entries in a massive, international design contest.

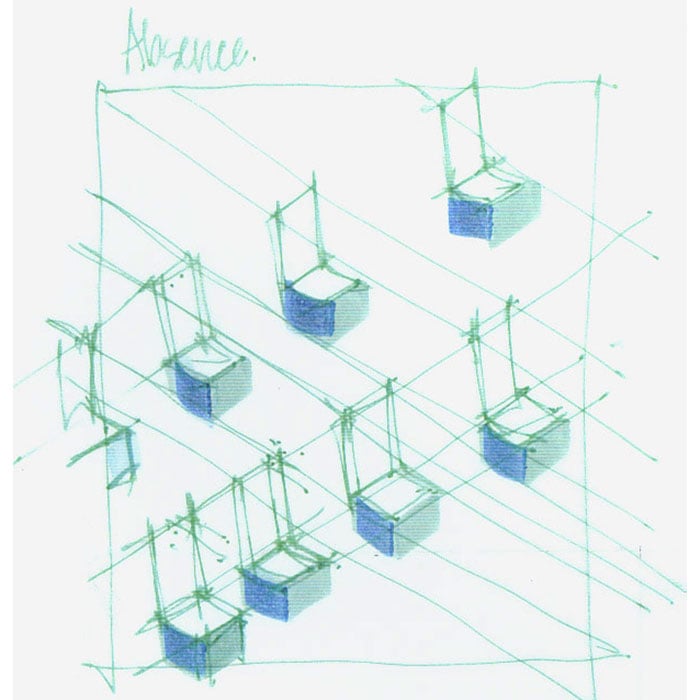

On June 24, 1997, the committee unanimously selected the design of husband-and-wife team Hans and Torrey Butzer from more than 600 submissions. The Butzers had read the biographies of all 168 people who died in the bombing and landed on a powerful centerpiece for their design – one empty chair for each person lost in the blast.

“It’s a beautiful design, very elegant, but inviting at the same time,” said Dupré. “And it uses the homely symbols of the chairs, the humble chair, to…recreate that sense of loss, that someone is missing.”

In the memorial’s various rooms and symbols, different elements come together, which Dupré says responds directly to “all the different ways that people have of grieving.”

That also meant making some slight tweaks to the original design in order to preserve elements that had become sacred to the local community in the weeks and months following the tragedy.

One of those was a tree that sat only 100 feet from where the bomb exploded but that had somehow survived. The Survivor Tree, as it had come to be known, needed to remain.

Additional community input also resulted in the preservation of a piece of the Murrah Building itself. Names of survivors were etched into that wall so that they and the wall together bear witness to what happened that day.

And though the initial plan was to disassemble the fence surrounding the site, community members fought to have a piece of it, too, preserved in the final design.

But the dominant feature of the site is the chairs, arranged in nine rows on the very spot where the nine-story building once stood. Smaller chairs commemorate the 19 children who were lost. Each of the 168 chairs is etched with one victim’s name.

While the Oklahoma City National Memorial offered plenty of lessons about how to honor what terrorism has taken away, Dupré and others say that it also has continued to provide lessons in something even more important: how to listen to those left behind.

“We call it sacred ground,” said Amy Downs, walking through the memorial on a recent summer day. She said she and other survivors gather there every year on the anniversary.

“Every time we’re here, we feel like we’re on sacred ground. This place is beautiful…and it’s peaceful. I mean, it does represent something very dark and tragic that happened. But it also represents the human spirit of resilience that was shown afterwards and the way people came together.”