The Statue of Liberty

The Statue of Liberty

Learn how the statue we think of as a beacon to immigrants was conceived by Frenchman Edouard Laboulaye as both a celebration of America’s democracy and a rebuke to his own nation’s autocratic rule.

The Statue of Liberty was conceived by French intellectuals in the shadow of the American Civil War as a gift celebrating the abolition of slavery, the preservation of the Union, and their continuing hope for a nation founded on the principles of individual liberty and equality.

It was also an elaborate act of protest against French authorities.

On an evening in June 1865, two months after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and one month after the last Confederate general surrendered to the Union army, they gathered for what would become a historic dinner party.

Their host was Édouard René de Laboulaye, a French professor who specialized in American history and who was a staunch abolitionist. Laboulaye and his friends were fed up with the authoritarian rule of Emperor Napoleon the Third, his criminalization of political opposition, and his open support of the American Confederacy.

After dinner, the professor and his guests drank brandy, smoked cigars, and discussed ways they could show the American people that not everyone in France agreed with their leader.

Laboulaye, in particular, was eager to criticize the French authoritarian government without becoming a target of persecution or imprisonment. He suggested presenting the people of the United States with a gift –a monument that would celebrate the place that America held in the global imagination as a beacon of liberty and democracy.

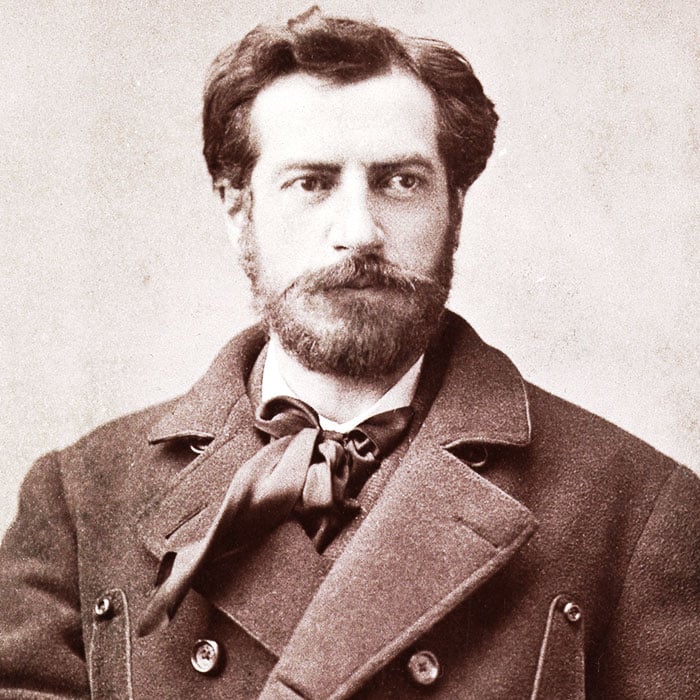

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, a French sculptor and architect, was among the guests at Laboulaye’s dinner party. He would later go on to design and build the monument, with Laboulaye as his primary patron and advisor.

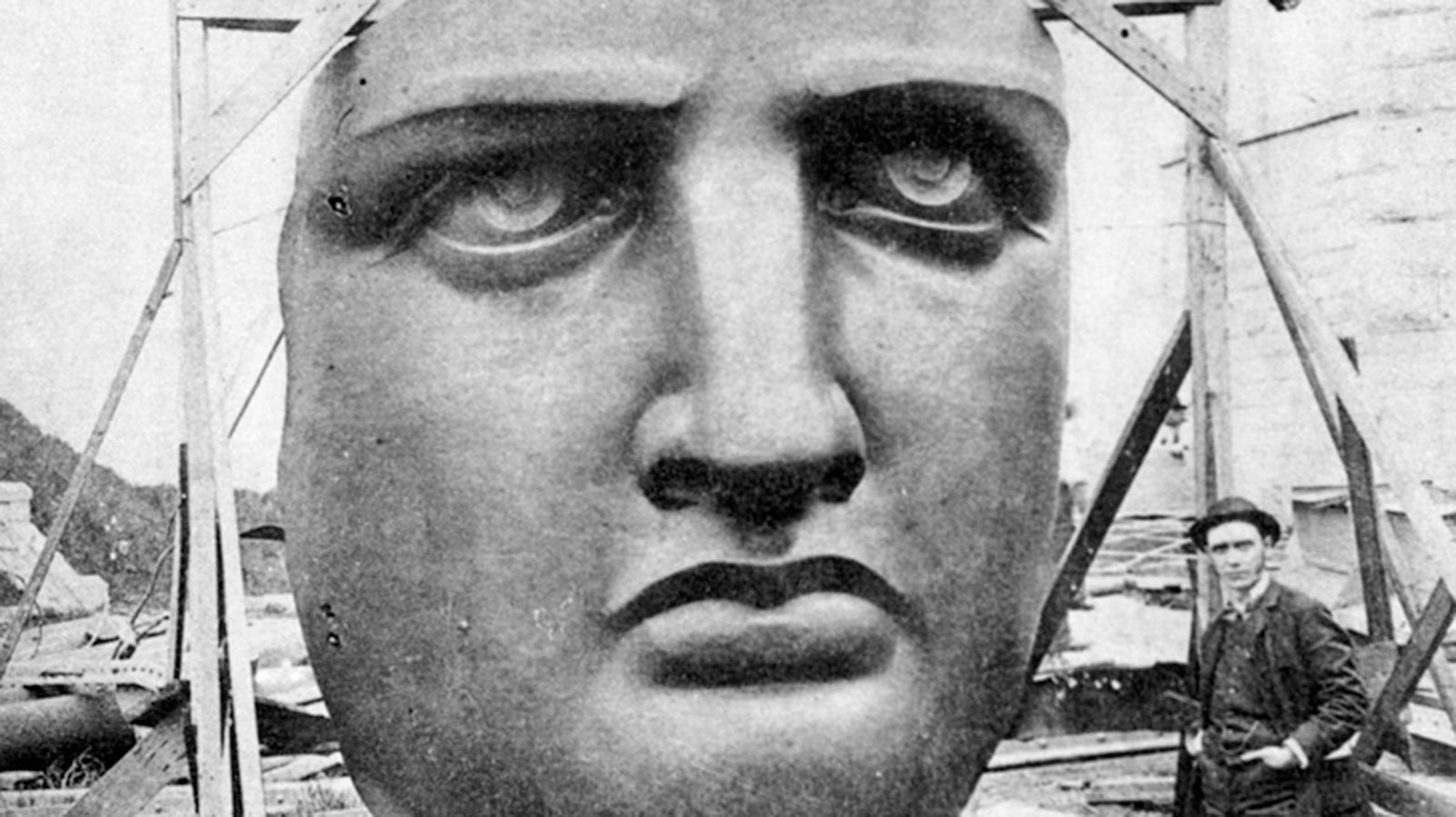

But that night was only the beginning of their monumental project. For years following that dinner party, Bartholdi workshopped designs. He took as his primary inspiration the Roman deity Libertas, the personification of personal freedom. Depicted on the official Seal of the French Republic of 1848, the ancient idol would provide a thinly veiled comment on what he saw as the profound hypocrisy of the French government. Bartholdi’s incarnation would be grand in stature, like the Greek Colossus of Rhodes. In one hand, she would hold up a torch of enlightenment. In the other, she would cradle the book of law, the foundation for American freedom. From her crown would emanate seven points for seven continents, symbolizing how her inspiration spreads. At her feet would lay the broken chains of tyranny.

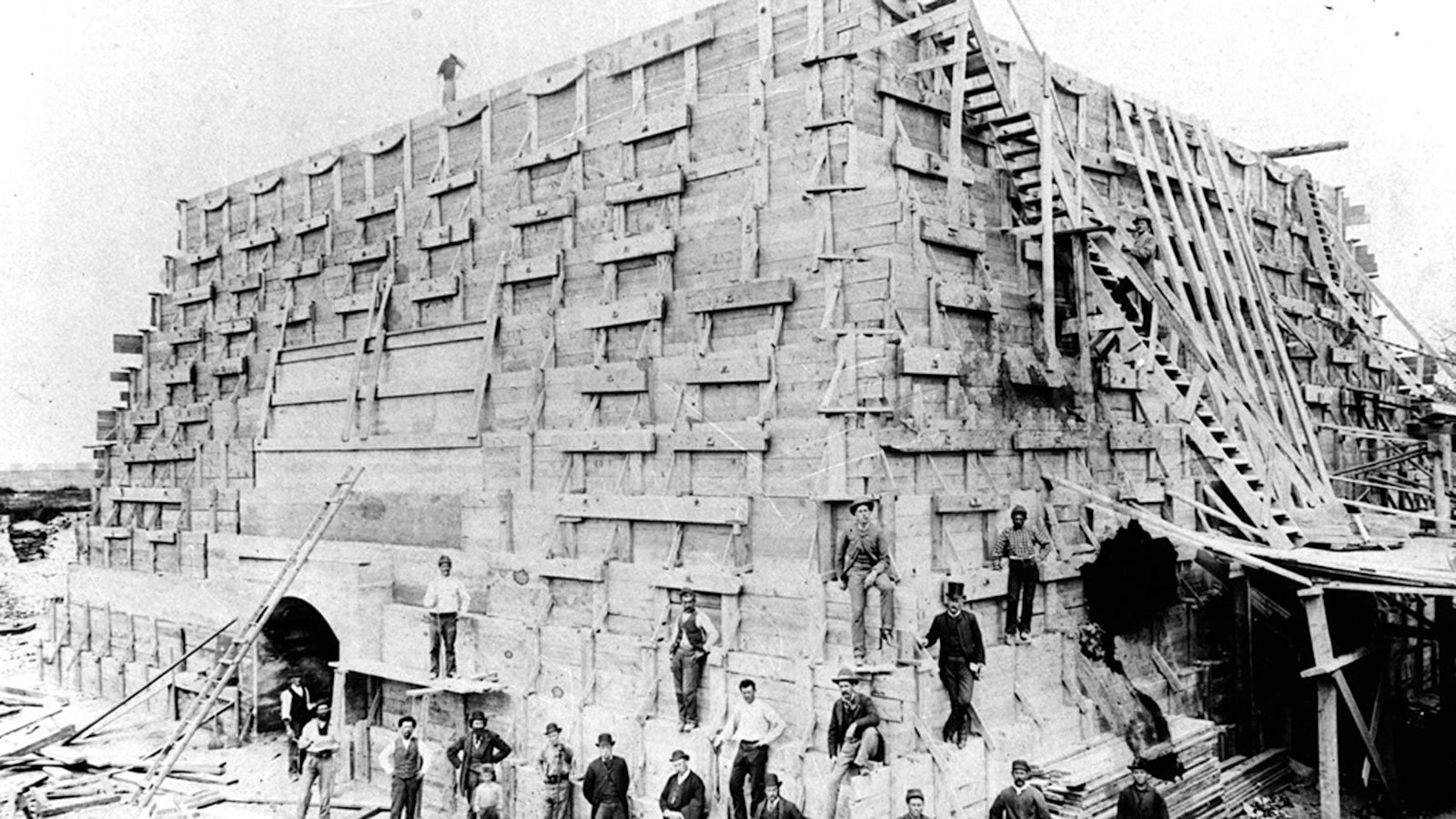

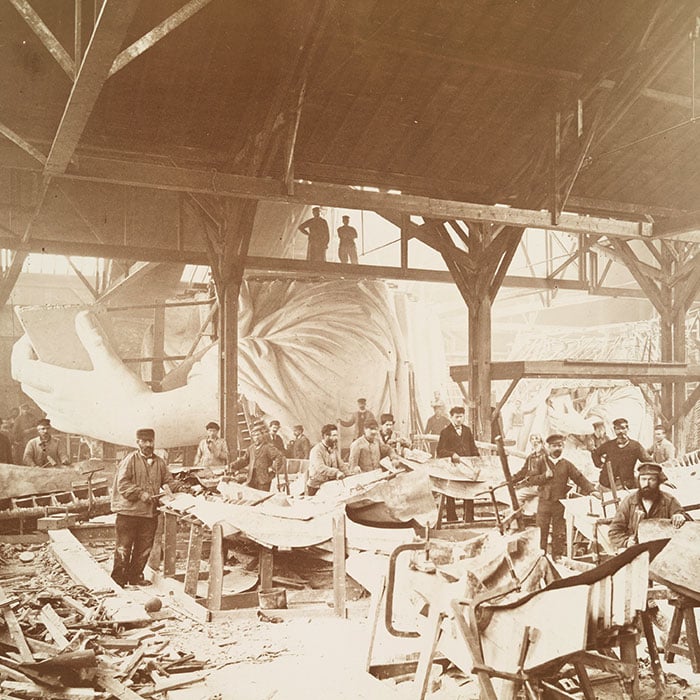

The final design was not only an artistic achievement, she was also a triumph of engineering. To prevent her from swaying or toppling in the wind, French bridge builder Gustave Eiffel built an iron tower as an internal anchor. It was a precursor to his famous tower that today towers over Paris.

Bartholdi assembled the giant copper figure, which he dubbed “Liberty Enlightening the World," in the courtyard outside his Paris studio, where she caused a sensation. He funded his work in large part through donations from the French people.

But in America, many were wary of the gift and the associated costs. In the decades following the Civil War, both public and private resources were depleted, and a large pedestal would be needed to display such a grand statue.

Bartholdi needed to spur more interest in America. So, although he was eyeing an island at the entrance to the New York harbor, Bedloe's Island, he sent Liberty’s torch-bearing hand to the 1876 Centennial Exposition in nearby Philadelphia.

The exhibit became a huge hit, and soon after, a private committee was formed in the U.S. to raise funds for Liberty’s pedestal. But its efforts fell far short of its goal. Meanwhile, New York Governor Grover Cleveland refused to contribute any money from the state budget. And while Congress authorized the acceptance of the statue and granted Bartholdi the rights to display it on Bedloe’s Island, legislators didn’t appropriate any federal funds for the project.

The torch-bearing hand was moved to Madison Square Garden, and the rest of the statue was shipped in 210 wooden crates. But they sat there, idle, for nearly a year. Other cities, including Philadelphia, began devising local proposals to give Lady Liberty a home in their cities.

But then, in the eleventh hour, newspaper magnate Joseph Pulitzer got involved. He launched a successful crowdfunding campaign. In an article in the New York World on March 16, 1885, he urged readers to open their pocketbooks:

We must raise the money!...The $250,000 that the making of the Statue cost was paid in by the masses of the French people –by the working men, the tradesmen, the shop girls, the artisans –by all, irrespective of class or condition. Let us respond in like manner. Let us not wait for the millionaires to give us this money. It is not a gift from the millionaires of France to the millionaires of America, but a gift of the whole people of France to the whole people of America.

Pulitzer promised to publish donors’ names in his paper in exchange for contributions of any size. Roughly 125,000 people contributed and, within five months, Pulitzer collected more than $100,000, most of it through small donations of one dollar or less. Whether intentional or not, the move also turned out to be a stroke of marketing genius. Sales of the New York World skyrocketed when locals rushed to buy souvenir copies on the days that their names were published.

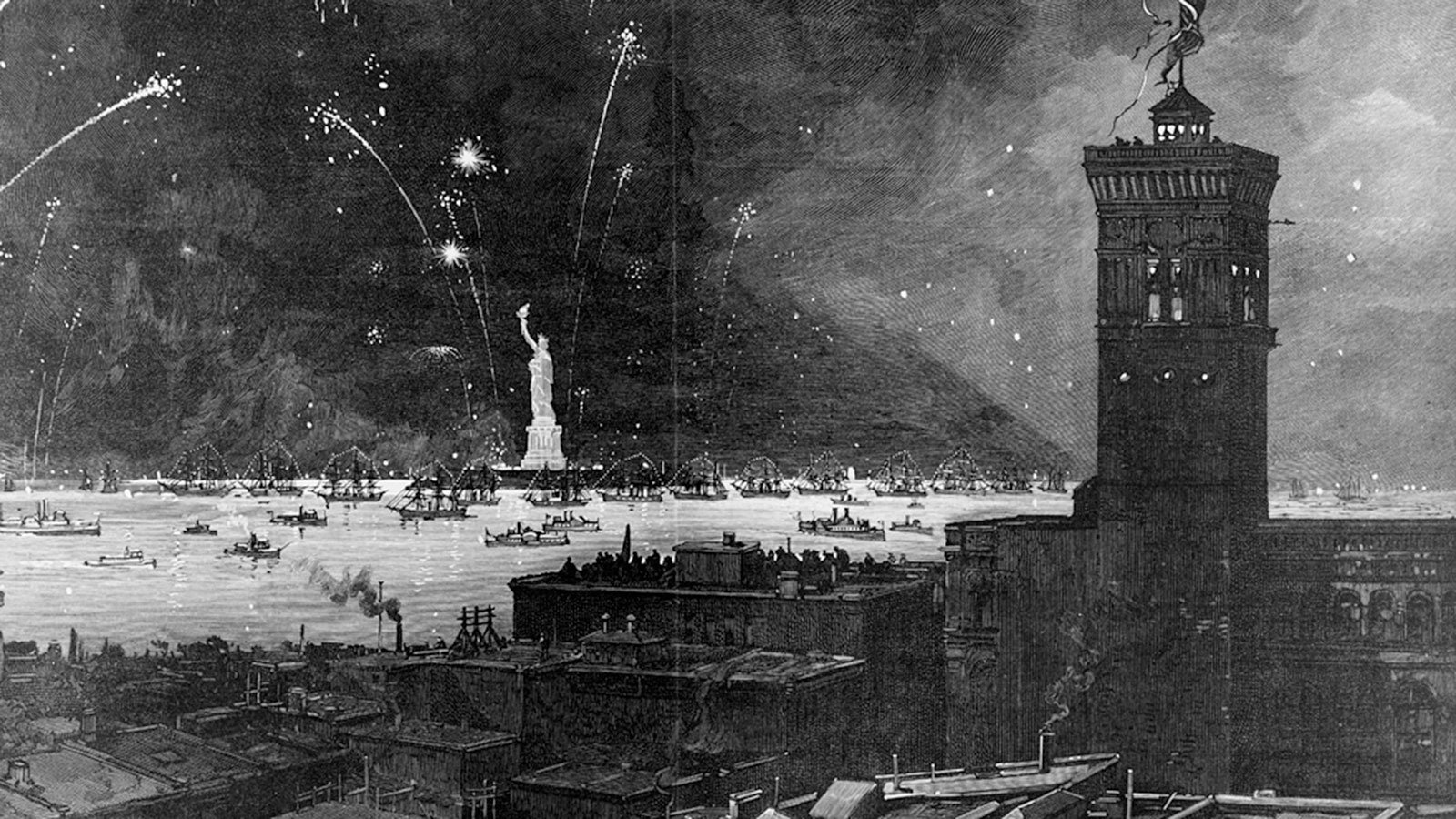

The following year, the statue and its pedestal were finally ready.

On October 28, 1886, Bartholdi unveiled his statue before a crowd of an estimated one million. Rising 151 feet above its 89-foot pedestal, Liberty Enlightening the World, became the tallest structure in New York City.

But her ideals were more a goal than a reality, even for people who lived on her shores. And she immediately became a rallying point for Americans involved in myriad struggles.

Aside from two French guests of the construction and design team, women were prohibited from attending the unveiling ceremonies. Organizers claimed they couldn’t guarantee their safety in such a large crowd. Suffragettes, in protest, chartered a boat to circle the island during the festivities, blasting their protest speeches towards the crowds.

Likewise, the black-owned Cleveland Gazette, which covered the unveiling extensively, pointed out that though the broken shackles at the statue’s feet were a powerful symbol, genuine freedom remained elusive for many African-Americans:

Shove the Bartholdi statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the ‘liberty’ of this country is such as to make it possible for an industrious and inoffensive colored man in the South to earn a respectable living for himself and family, without being ku-kluxed[,] perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed. The idea of the ‘liberty’ of this country ‘enlightening the world,’… is ridiculous in the extreme.

Six years later, when neighboring Ellis Island opened its doors in 1892, many immigrants who landed there were turned away or, if they made it ashore, discriminated against once they entered America’s cities and towns.

.jpg)

Still, when they passed by Liberty’s torch, they, too, recognized her as a symbol of welcome and of promise. Americans also embraced this new meaning. In 1903, Emma Lazarus’s sonnet “New Colossus,” written in 1883 to help raise funds for Liberty’s pedestal, was emblazoned on a bronze plaque. Her words now sit beneath the statue, and a portion of the poem is regularly cited as an American creed:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

Today, the Statue of Liberty continues to be a powerful international symbol, a flashpoint for debates about what inclusion, freedom, and democracy ought to mean. Her likeness has been recreated for display in pro-democracy protests in Beijing and in political art the world over.

And although the interpretation of her meaning often shifts, depending on the viewer, she remains a resilient reminder of the values and ideals that America was founded on, that its people continue aspiring to, and the hope she represents to many immigrants, refugees, and liberty-seekers throughout the world.