Boston Post Road

Boston Post Road

Travel the highway that helped win the American Revolution and served as the nation’s first “information superhighway.”

The British crown supported the development of America’s first regular postal system and the highway that made it possible, believing they would help unify the colonies and assist them in fending off their Dutch invaders. But in the end, the increased communication helped the colonists drive off the British themselves.

“You could see the [Boston] Post Road, in many senses, as the infrastructure for the rebellion,” said Eric Jaffe, author of The King’s Best Highway: The Lost History of The Boston Post Road, The Route That Made America.

Early American settlements were mostly dispersed coastal outposts. Intercolonial communication was severely limited and inconsistent. If a royal governor in Boston, Massachusetts, for example, wished to send news to his counterpart in Williamsburg, Virginia, it could take a full eight weeks for that letter to arrive.

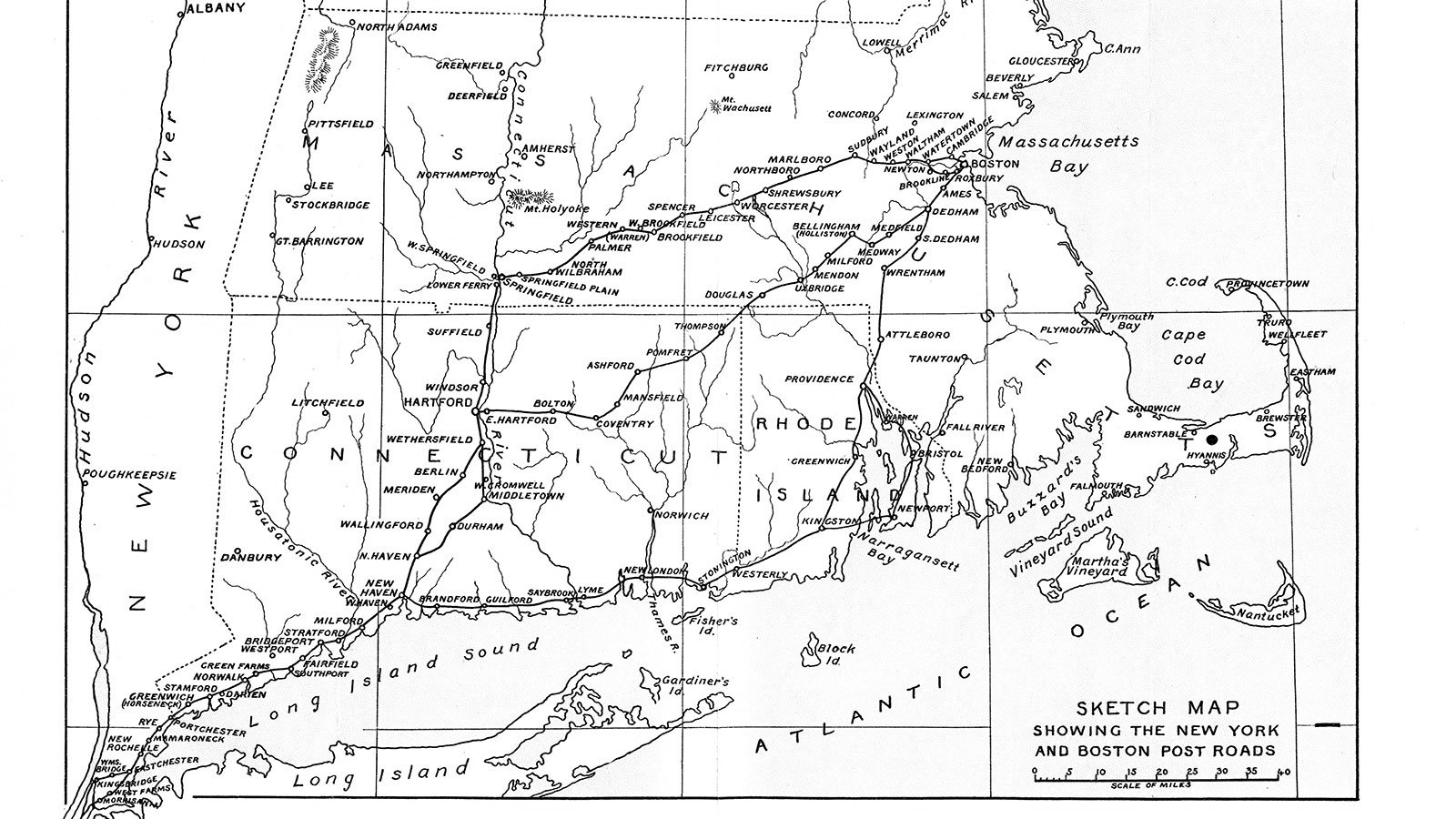

Those weak lines of communication presented a problem for Francis Lovelace, the royal governor of New York. In 1672, the Dutch were threatening to recapture his colony, and he was eager to receive any intelligence about their movements. Lovelace worked with the royal governor of Connecticut to create a strategic intercolony postal system connecting New York and Boston. It would travel along a route that he billed as the “King’s Best Highway,” or the Boston Post Road.

“Colonies would exchange information, they’d exchange news, you’d hear about ships arriving perhaps in time to set up enough of a foundation, enough of a defense to…be able to hopefully stop an invasion,” explained Jaffe.

Like most early colonial roads, the route for the Boston Post Road would take advantage of a series of crude wagon routes and established Native American roads – today known as the Bay Path, Connecticut Path, and the Pequot Path.

Since the route was initially treacherous to navigate, with knotty roots, narrow passes, seasonal variations, and long expanses without any formal lodging, Lovelace suggested it be staffed by a post rider who was “active, stout, and indefatigable.” That lone postal rider on horseback would be responsible for scouting out the best trail and postal stops and would carry an axe to carve slashes in the trees along his path and mark the way for those who would follow.

On January 22, 1673, the very first rider took the postmaster’s oath of fidelity, written by Lovelace, and headed out from the southern tip of Manhattan toward Boston. His goal was to make the trip in just two weeks before circling back so that the postal service could be reliably offered on a monthly basis.

The rider traveled from Manhattan to New Haven and Hartford, then on to Springfield, Worcester, and through Roxbury into Boston, where his arrival was met with cheers and celebration – even though that first journey took closer to three weeks to complete.

Early post riders delivered the mail to taverns, which in those days were open to all, including women and children. They operated more like all-in-one rest stops and community centers, with lodging, stables, and of course, a bar. Post riders would arrive with news from their travels, and townspeople would gather to hear the news and gossip and see what correspondence he might have brought.

In 1692, British King William and Queen Mary formalized the colonial postal system. They ordered New Jersey Governor Andrew Hamilton to establish official postmasters in each of the existing colonies and expand the route south into Virginia and north into New Hampshire.

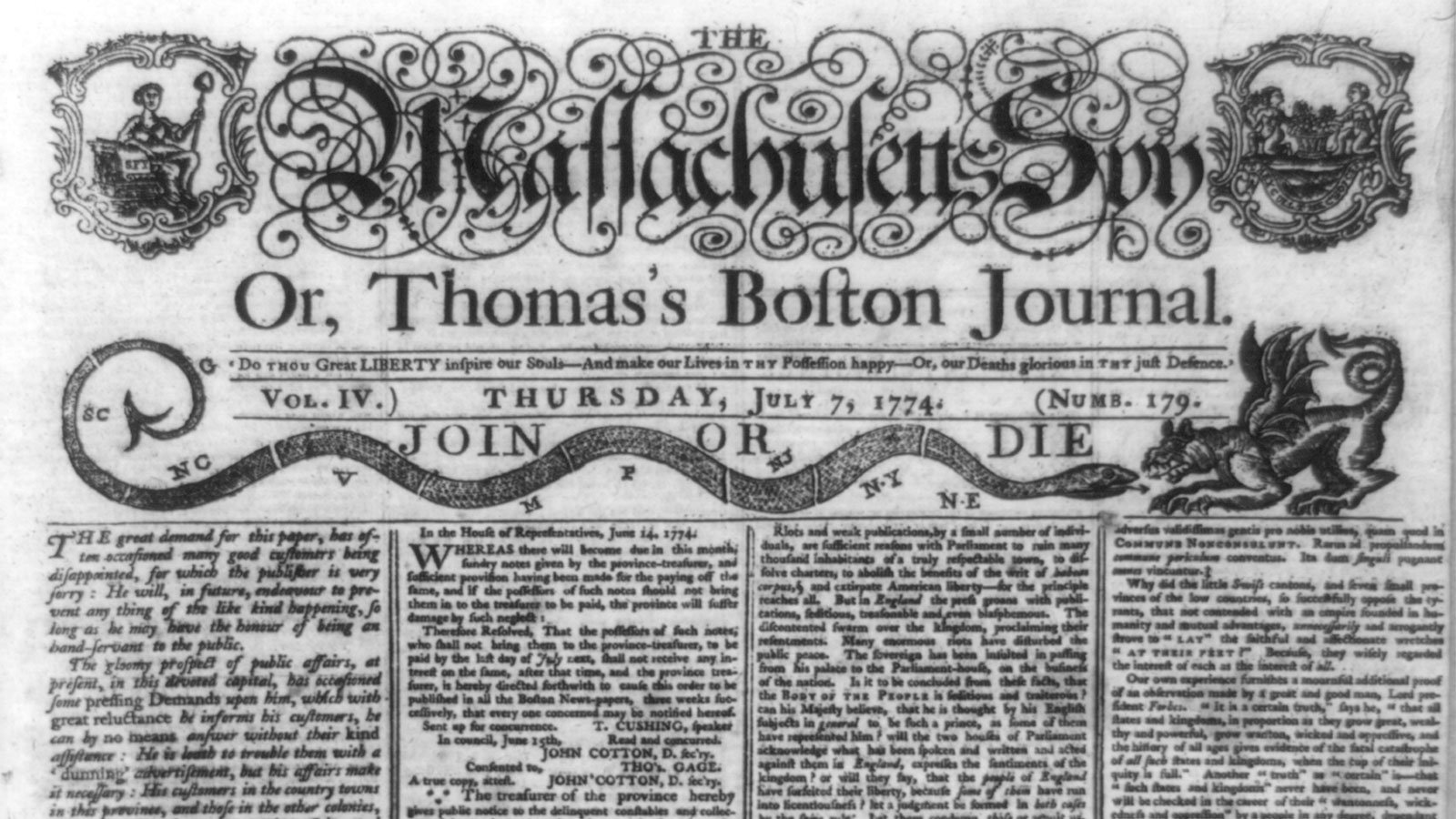

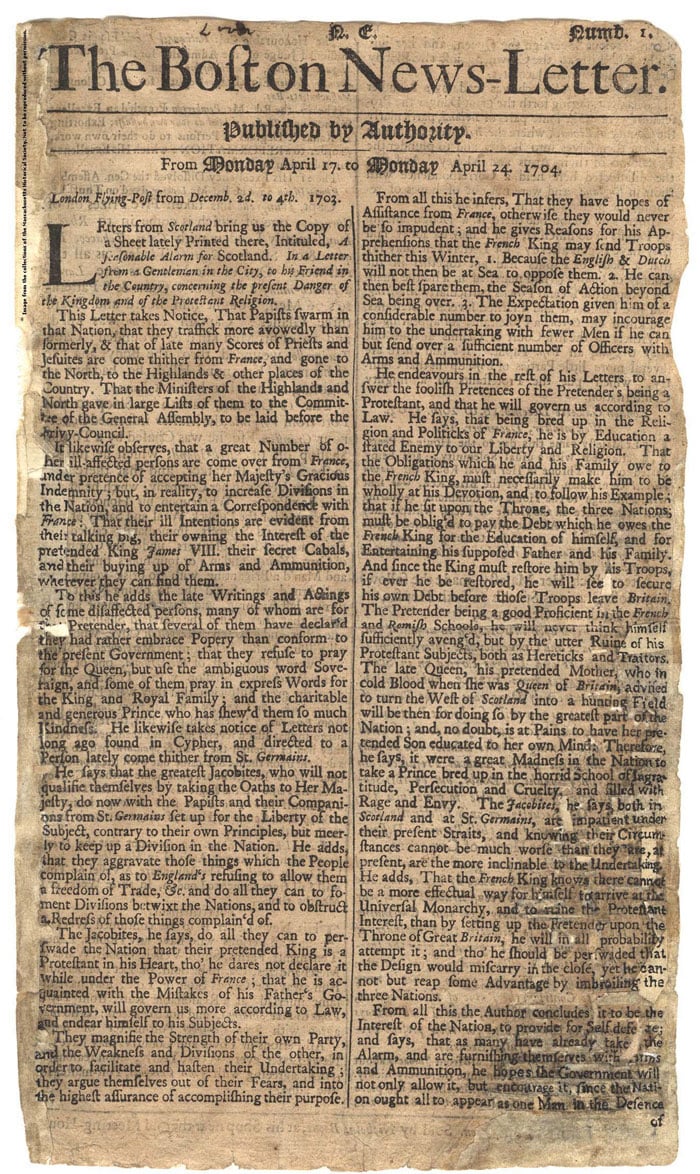

In time, the post riders and tavern owners formalized their role as collectors and disseminators of news. In 1703, at the request of Governor Fitz-John Winthrop of Connecticut, a postmaster named John Campbell compiled his discoveries in a report. He soon began making copies and sharing his reports with other government leaders and select friends. By 1704, Campbell began selling his Boston News-Letter to the general public. The first issue was a single sheet, printed on both sides. It contained not only tales from his travels in the colonies, but also news from England, cribbed mainly from London periodicals. Campbell’s Boston News-Letter is considered America’s first successful newspaper, and it survived for 72 years.

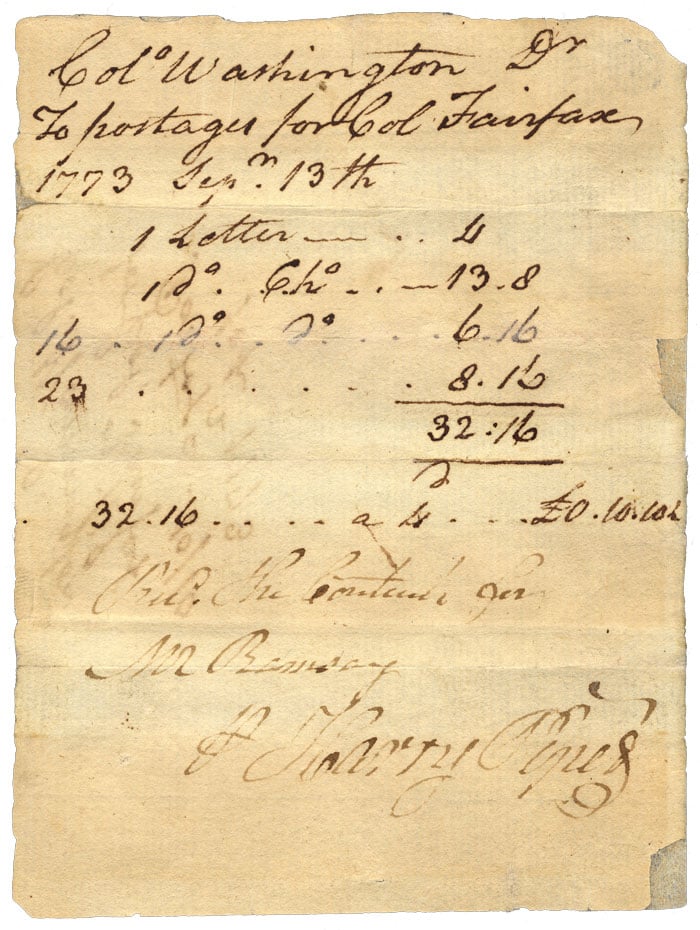

Without a stamp system and organized pay scale, the postal service struggled for some time to collect enough money to operate efficiently. Costs varied depending on the fee collector, and writers sent letters free of charge, with the recipient bearing the responsibility for paying for their mail upon receipt. Some recipients, such as then-member of the Virginia House of Burgesses George Washington, were allowed to accrue debt with the postal system.

It meant that the postal system was taking a financial risk with each delivery.

“If your letter arrives and the recipient says, ‘You know what? I don’t really want this letter,’ or ‘I’m not going to pay you,’ guess who’s out? It’s the postmaster,” said Jaffe.

Service declined until it trickled to a near standstill.

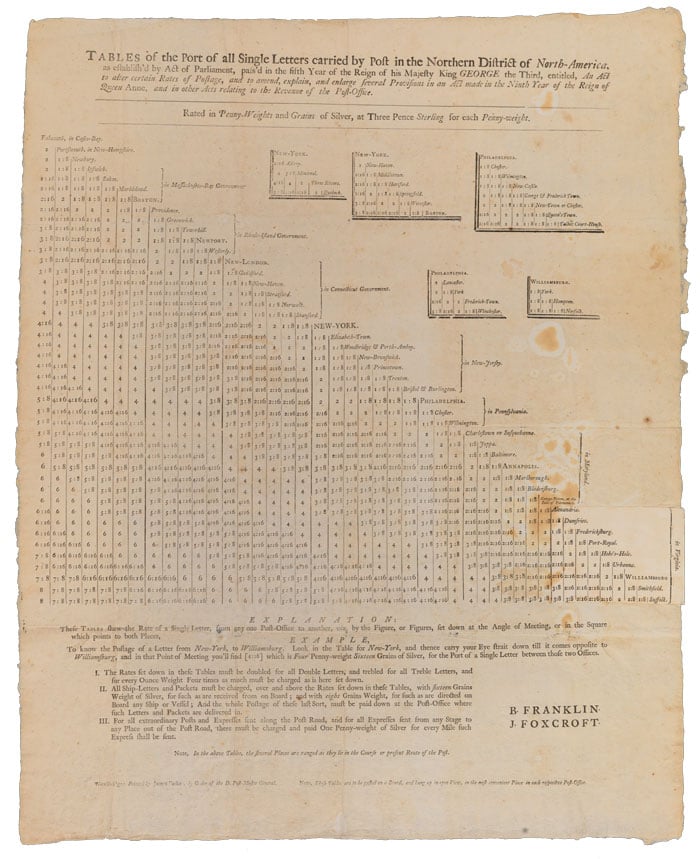

Then in 1753, Benjamin Franklin, who had long served as the postmaster of Philadelphia, took over as one of two deputy postmasters of North America and infused a new level of efficiency into the system by establishing postage rates based upon miles between destinations.

“He takes for the first time, a very analytical, scientific approach to organizing the post office,” said Jaffe. “In many ways what he did was…[lay] the basic foundation for the postal system that exists today.”

The rates Franklin calculated became effective October 10, 1765 and were displayed at all post offices in the colonies. They remained unchanged until the American Revolution.

“Soon you begin to see kind of a real business operation emerge,” said Jaffe.

You also began to see a broader, quicker, and more reliable exchange of information and ideas among the colonies. And in time, those ideas would help sow the seed of revolution.

As the post office became a more lucrative venture, Britain found its coffers strained from fighting wars on multiple fronts, and began to seek ways to make more money from its operations in America.

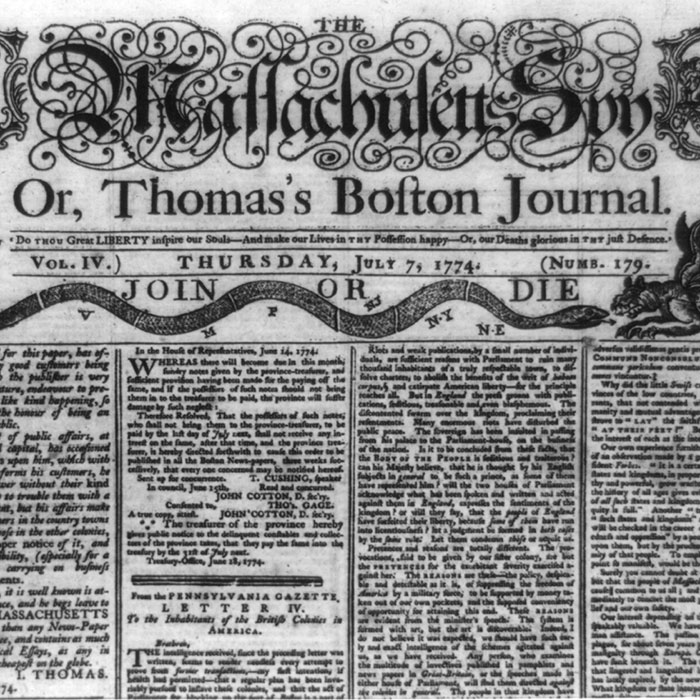

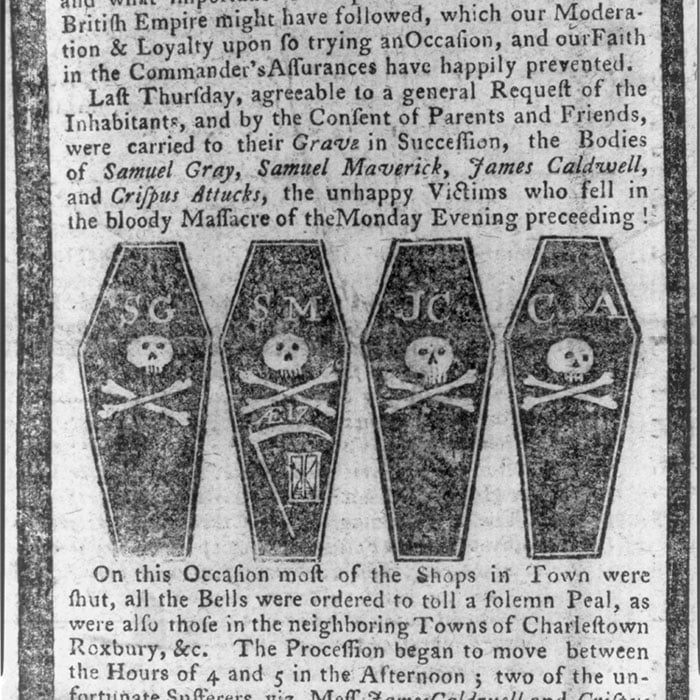

In 1765, Parliament passed the Stamp Act requiring that newspapers and several other materials printed in the colonies be produced on more expensive, stamped or embossed paper imported from London. The move sparked outrage in the colonies, particularly among newspaper publishers, many of whom were still post riders. They began to print op-eds, many of them under pseudonyms, and disseminate news about demonstrations against the Stamp Act that sprang up throughout the colonies.

In time, the patriots begin to abandon the crown’s postal system and, along the same Boston Post Road, establish their own renegade postal networks among people sympathetic to the anti-British cause whom they could trust to carry their subversive news and communications. Illegal “committees of correspondence” were organized in each colony by leading regional patriots to exchange messages along the Post Road. Paul Revere became one such rider, and he carried news of the Boston Tea Party, written by Samuel Adams, to New York’s Sons of Liberty the morning after the event.

“The British weren’t involved,” said Jaffe. “That meant they didn’t get any revenue from this postal system. That meant that you couldn’t intercept a message. What you start to see is a functioning American system.”

Revere also carried news from the Continental Congress in Philadelphia to Massachusetts along the same Boston Post Road.

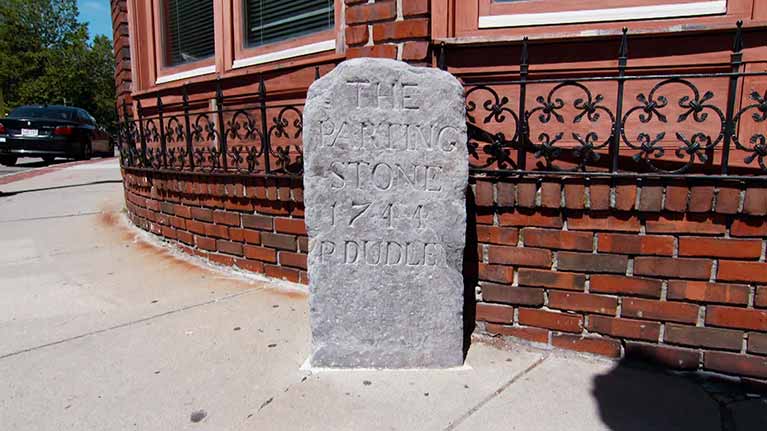

Many historic remnants -- including taverns, mile markers, and even Native American artifacts -- can still be found along today’s Boston Post Road.

And the morning after Paul Revere rode into history on the eve of the Battles of Lexington and Concord, another set of messengers made their way along the Post Road – one taking the inland route and one taking the coastal route – spreading word that fighting had broken out, and the rebellion had begun.

“Eventually it reaches New York, and of course they erupt in joy,” said Jaffe.

Centuries later, there are many speedier ways to relay information and to travel along the Atlantic coast. But several of the mile markers, pathways, and structures along the Boston Post Road remain, paying homage to the people – post riders, journalists, inventors, tavern owners, and revolutionaries – who made America possible.