Kalamazoo Mall

Kalamazoo Mall

In the late ’50s and ’60s, shoppers were abandoning traditional downtowns for suburban malls. See how Kalamazoo turned “Main Street” into a pedestrian mall, a pattern that would play out with mixed results across the nation.

In the second half of the twentieth century, many American cities were in a state of crisis as people flocked to the suburbs.

Lynn Houghton, regional history collections curator at Western Michigan University libraries, says that the tipping point in Kalamazoo, Michigan, came in the early fifties when Sears, Roebuck and Company announced that they were following the shoppers and heading for the suburbs.

“It wasn’t that far, but it was far enough that I think panic was beginning to set in,” said Houghton.

So Kalamazoo property owners and retailers got together and decided that something needed to be done. But what?

To combat the problem of shopping malls taking their business, they hired the man who invented the modern shopping mall: Victor Gruen, an Austrian-born architect.

“They brought him here to see what he could come up with,” said Houghton. “I don’t want to say that they were desperate, but they wanted to do something that I think would shake things up.”

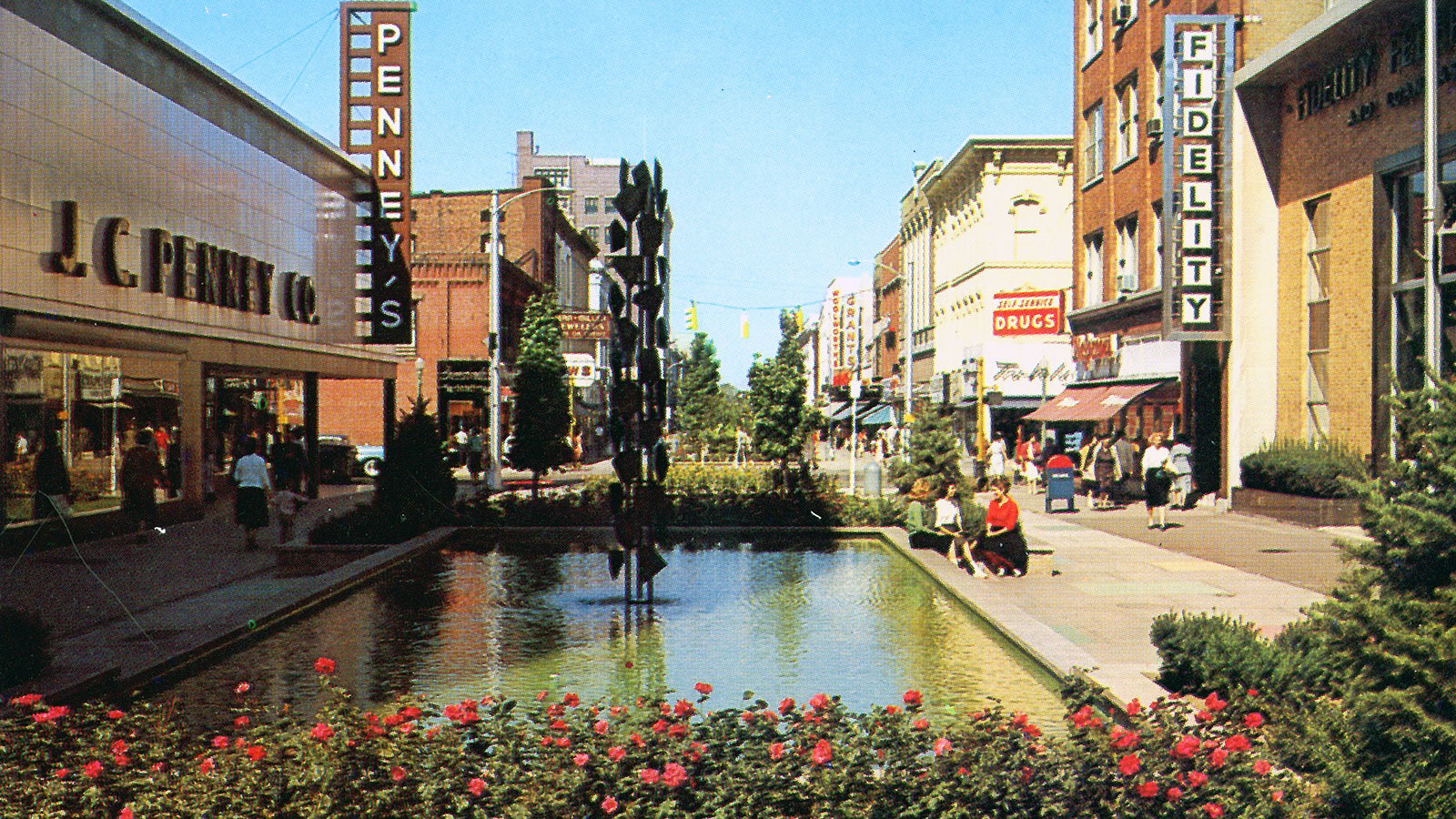

Gruen’s plan for Kalamazoo was to create the country’s first pedestrian mall on a downtown street, closing the street to traffic and creating an area for shoppers, replete with landscaping, seating areas, and public art. It was a radical vision at the time and was quickly duplicated in roughly 200 cities across the country before being almost completely phased out – only to have many of its elements resurrected in recent years as cities undergo yet another period of dramatic transformation and reinvention.

Gruen’s mall designs grew out of his experiences as a refugee. An Austrian-Jewish immigrant forced to flee the Nazis, Gruen had fond memories of the vibrant Vienna streets of his pre-war childhood.

“In a way what he tried to do was bring Vienna to America,” said Peter Norton, a historian of engineering and society at the University of Virginia and an expert on the evolution of America’s streets. “In other words, bring the shopping experience where you walk and meet people and interact with people. A sociable experience.”

Central to this idea of a sociable street was the eradication of what Gruen called the “tyranny of the automobile,” which caused gridlock, spewed noxious fumes, and kept residents isolated from one another and from retailers.

So Gruen offered a three-part plan for Kalamazoo’s liberation: first, a ring road to circle the central business district; second, parking lots to be constructed just outside of that business district; and finally, a car-free, pedestrian mall where residents could freely stroll and socialize.

Gruen’s car-free street would create a feeling of safety and security so that residents would feel more at ease lingering and, of course, spending money.

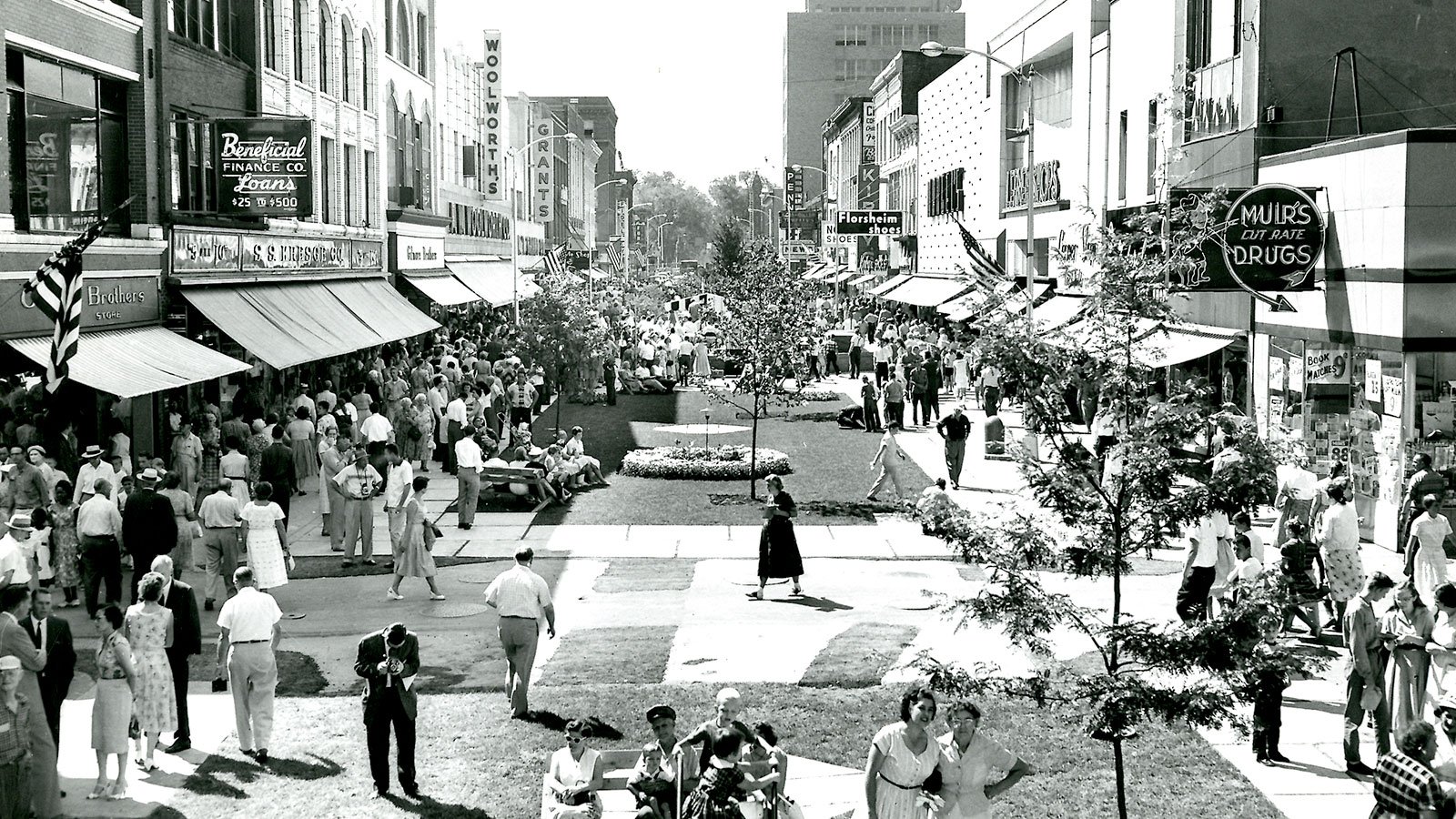

On March 23, 1959, the Kalamazoo City Commission unanimously approved an ordinance that would close two blocks of South Burdick Street, one of the city’s main commercial arteries, to automobile traffic.

However, points out Houghton, Kalamazoo leaders chose not to adopt the other two elements of Gruen’s plan – the ring road and the parking areas.

“I think that the people here in Kalamazoo felt that they could just do the one,” she said.

Still, they landscaped the two-block mall, built fountains, and installed benches and other places to sit.

Initially, the pedestrian mall was a success. Retail traffic increased, as did property values. Two large department stores opened locations on either side of the mall.

The year after it opened, a third block was added and then a fourth. City leaders financed public art projects along the mall and built a playground.

And the experiment was not limited to Kalamazoo. Cities across the country adopted Kalamazoo’s model in a bid to salvage their own downtown areas.

But ultimately, these pedestrian malls couldn’t compete with the forces of suburbanization. After the initial interest wore off, foot traffic began to decline. Shoppers complained that there wasn’t enough parking compared to suburban malls. And as fear of crime and drugs increased throughout the country in the ‘80s, downtown Kalamazoo once again became desolate. In 1998, all but two blocks were reopened to cars.

The same pattern played out in towns across America. Of the roughly 200 cities that emulated Gruen’s Kalamazoo experiment, some 85 percent of them reversed course by the 1990s.

“As attractive as it may have been,” said Kroloff of the pedestrian malls, “[it] was a bandage on an amputated leg. There’s very, very little that it could do to change something that was much bigger than it was. It was a good attempt, it was an interesting attempt, but it could not compete...especially in these smaller cities where there just wasn’t enough…accumulation of things in the downtown area that weren’t simply shopping.”

“[Gruen] didn’t understand…the vastness of the forces arrayed against the cities,” said Kroloff.

But today it appears that perhaps Gruen was simply ahead of his time.

In recent decades, as people and dollars have been flowing back into urban centers, some key elements of the pedestrian mall are making a comeback.

In one of the busiest intersections in New York City, for example, city planners closed lanes of car traffic in 2009 to create spaces for people to walk, bike, or sit and socialize. An eight-month trial period was so successful that Times Square remains car-free to this day. Meanwhile, in other cities across the country, several other elements of the pedestrian mall – including limiting or removing car traffic, increasing space for pedestrians, and making the streets more friendly to bicyclists – are seeing a resurgence in popularity.

Reed Kroloff predicts that this is only the beginning and that city planners will continue seeking ways to make their downtowns less car-centric and more welcoming to people on bikes, on foot, or wishing to just sit still and enjoy their surroundings.

“It’s working now because people want to be in the city,” said Kroloff. “People aren’t enjoying the hermetic seal that a suburban shopping mall offers in the way that we were after World War II. We like the activity of a city.”