Woodward Avenue

Woodward Avenue

Join Geoffrey Baer in the Motor City for a ride in a Model-T on the first concrete-paved modern highway.

Woodward Avenue in Detroit has long been synonymous with car culture. Not only was it home to one of the first Ford factories, it was the site of some of the nation’s first street car races, as well as an array of drive-ins, car dealerships, and automobile accessory shops.

But the street existed long before the vehicle that made it famous, and retrofitting it to accommodate that “horseless buggy” was a bumpy ride, requiring invention, destruction, and widespread behavioral engineering.

“It wasn’t enough just to build cars, you also had to show how to build roads, and that was what Woodward was about,” said Robert Fishman, an urban historian at the University of Michigan's Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning.

The street was named for Augustus Woodward, who first came to Detroit in 1805 after Thomas Jefferson appointed him to be the first judge of the Michigan Territory.

“He immediately proclaimed that this would be the great city of the North American interior,” said Fishman. “All that it needed was a plan.”

And Woodward created that plan, which included a vast network of interlocking hexagons in the city center, with streets emanating from that center like spokes on a wheel.

In 1863, a horse-drawn streetcar began running down the center of Woodward Avenue, turning many of the lots lining the street into prime real estate.

“Many Detroit leaders were basically cutting down the great Michigan pine forests, so that all went into magnificent mansions up and down Woodward,” said Fishman. “It was one of the great American boulevards.”

Then, around the turn of the twentieth century, the state’s burgeoning automobile industry started attracting inventors, engineers, and suppliers to Detroit. In 1904, Henry Ford, who grew up nearly ten miles outside the city, opened a series of progressively larger factories near and along Woodward Avenue.

Within a decade, Detroit had become a national hub for the automotive and auxiliary industries, and Woodward Avenue had become its Main Street.

But the road itself was still designed primarily for horse-drawn carriages: a dirt road that became rutted with mud in the spring.

“It’s completely incapable of carrying the traffic that Ford and the other automobile manufacturers are providing for it,” said Fishman. “They basically rendered the whole transportation system of the United States obsolete, and the more people bought their cars, the more obsolete it became.”

If car owners were going to have safe and unencumbered places to drive their cars, American roads would need a complete overhaul – and it would all begin with Woodward Avenue.

In 1909, a mile-long stretch of Woodward became the first mile of American road paved with concrete. By 1916, the road was paved for 27 miles, all the way to Pontiac, Michigan.

Then there was a new problem: how to coordinate all the traffic. In 1920, a local police officer named William Potts developed the first manually operated, three-color traffic light and installed it along Woodward.

With cars now able to zip down Woodward at a speed previously unimaginable, the only thing standing in the way of the car-centered city of the future was the people. The number of pedestrian fatalities was soaring, particularly among children, who were accustomed to playing in the streets.

There seemed to be little that could be done about it. Until now, it had been culturally acceptable to walk in the street. The prevailing attitude was that the streets were made for everyone, and no mode of transportation had the natural right of way.

“Letters to the editor of the newspaper were overwhelmingly blaming the drivers and the cars,” explained Matt Anderson, curator of transportation at The Henry Ford museum complex. “As a result, you start to get proposals to restrict cars…to require cars to be equipped with a mechanical speed governor that would make it impossible for them to go over a certain speed.”

“This really terrified people who wanted to sell cars,” said Anderson. “They started to figure out they had to change the whole way this question was framed.”

Automobile industry leaders realized that there needed to be a paradigm shift. Streets needed to be redefined as places first and foremost for cars. Previously normal walking habits needed to be recast as reckless and backwards.

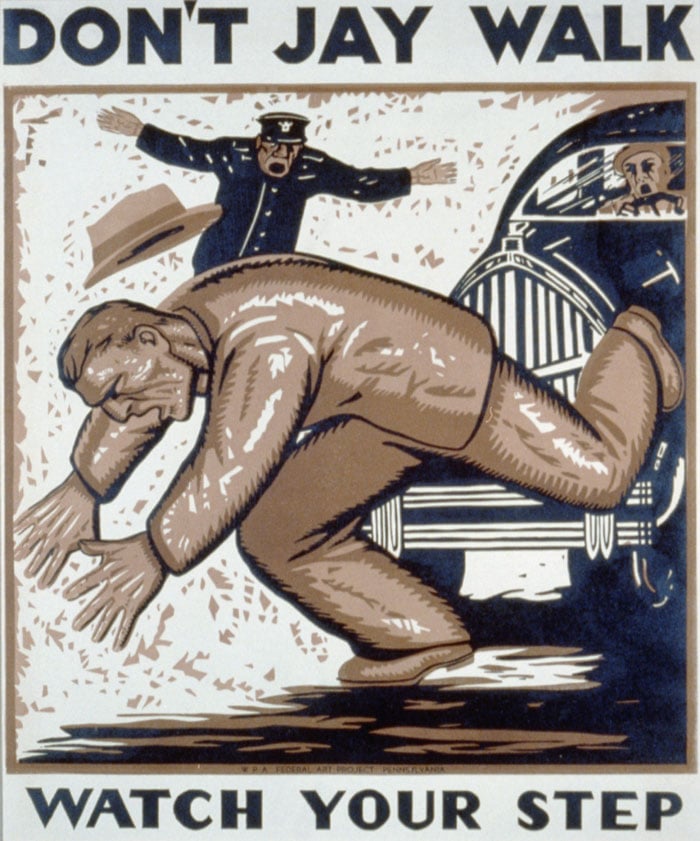

The auto industry began funding campaigns to shame those who walked in the streets – starting with the children.

Peter Norton, historian of engineering and society at the University of Virginia and author of Fighting Traffic: The Dawn of the Motor Age in the American City, said the first step was to try to equate the act of walking in the street with backwards thinking. They began by calling the people who participated in this formerly acceptable behavior “jays.”

“It would be like the word ‘hick’ today,” said Norton.

The main tool in their campaign was peer pressure. In 1925, more than a thousand Detroit school children gathered to witness the public trial of a 12-year-old boy accused of jaywalking.

As people began to stay out of the way and cars crowded out other forms of traffic, it became more and more popular to cruise down Woodward at high speeds. Eventually, the street became congested. And that created a new problem to solve.

Detroit city boosters and suburban real estate developers began pushing to widen Woodward Avenue, from four to eight lanes. They wanted to make it, in Fishman’s words, “the ideal of the automobile metropolis.”

“They knew very well that if their city was just caught in gridlock, it wasn’t going to thrive, no new factories were going to come,” said Fishman.

The new idea was to build a road called a “super highway,” a limited-access road that could accommodate both streetcars and automobiles but without traffic lights or cross traffic.

“The [Ford] factory implied a new kind of road and where better to build it than right in front of the factory itself,” said Fishman.

Auto executive and suburban real estate interests launched a publicity campaign to rally support for the wider street.

The Common Council adopted the plan to widen Woodward Avenue in April 1925, and a referendum on the measure passed that fall. But to widen Woodward, trees had to be razed. Buildings had to be demolished. One church was cut in half.

“It was urban surgery,” said Fishman. “Everything had to go, nothing was sacred. The highway was everything, the highway was the future.”

As it turned out, the changes weren’t wholly beneficial for Detroit. City leaders had believed that the wider street would allow suburbanites to drive downtown to work and shop. But instead, the new outlying business districts boomed, and Woodward’s inner-city stretches crumbled.

“It really turbo-charged suburbanization,” said Fishman. “A road like this opened up whole areas of cheap land at the edge for suburban development, and in effect, it devalued the land closer to the center.”

“City leaders thought…the more roads the better because they’ll just bring more people into downtown,” said Fishman. “They didn’t understand that the roads went in two directions.”

But further into its suburban reaches, Woodward Avenue thrived, particularly after World War II. Drive-in restaurants grew like mushrooms along its path, and the car culture entered its heyday. Up and down Woodward, automobile engineers street-tested their new cars while hot rod enthusiasts gawked and teenagers cruised the strip.

Today, Detroit's infamous struggles are giving way to signs of a renaissance. And city planners have taken a discarded idea from Woodward Avenue’s past as inspiration for its future.

A new streetcar line, dubbed the Q Line, opened in May 2017, carrying passengers through downtown Detroit along Woodward Avenue. The last car of Detroit's old streetcar system was numbered 286; the numbers for the new line start at 287, picking up where the old series left off.

“Woodward is becoming what they hoped it would be, a super highway that combines cars and transit,” said Fishman. “I think the great thing about the streetcar is it recognizes the wisdom of the 1920s planners that you need both cars and transit. If you’re going to really have a city, you have to have them both, and one of the great signs of Detroit’s recovery is that we’re coming back to a balanced transportation system.”

And so Woodward Avenue, once again, is becoming a model of the transportation system of the future.