Pullman, Illinois

Pullman, Illinois

In the 1870s, widespread railway strikes, inspired by workers' wage cuts, brought commerce across the U.S. to a standstill. This led to violent conflicts between police and workers, requiring military intervention to restore order in several cities.

Watch the Segment

A young Chicago entrepreneur named George Pullman, who had already made a fortune building luxury rail cars, saw an opportunity to expand his manufacturing operations and at the same time to create better relations with workers.

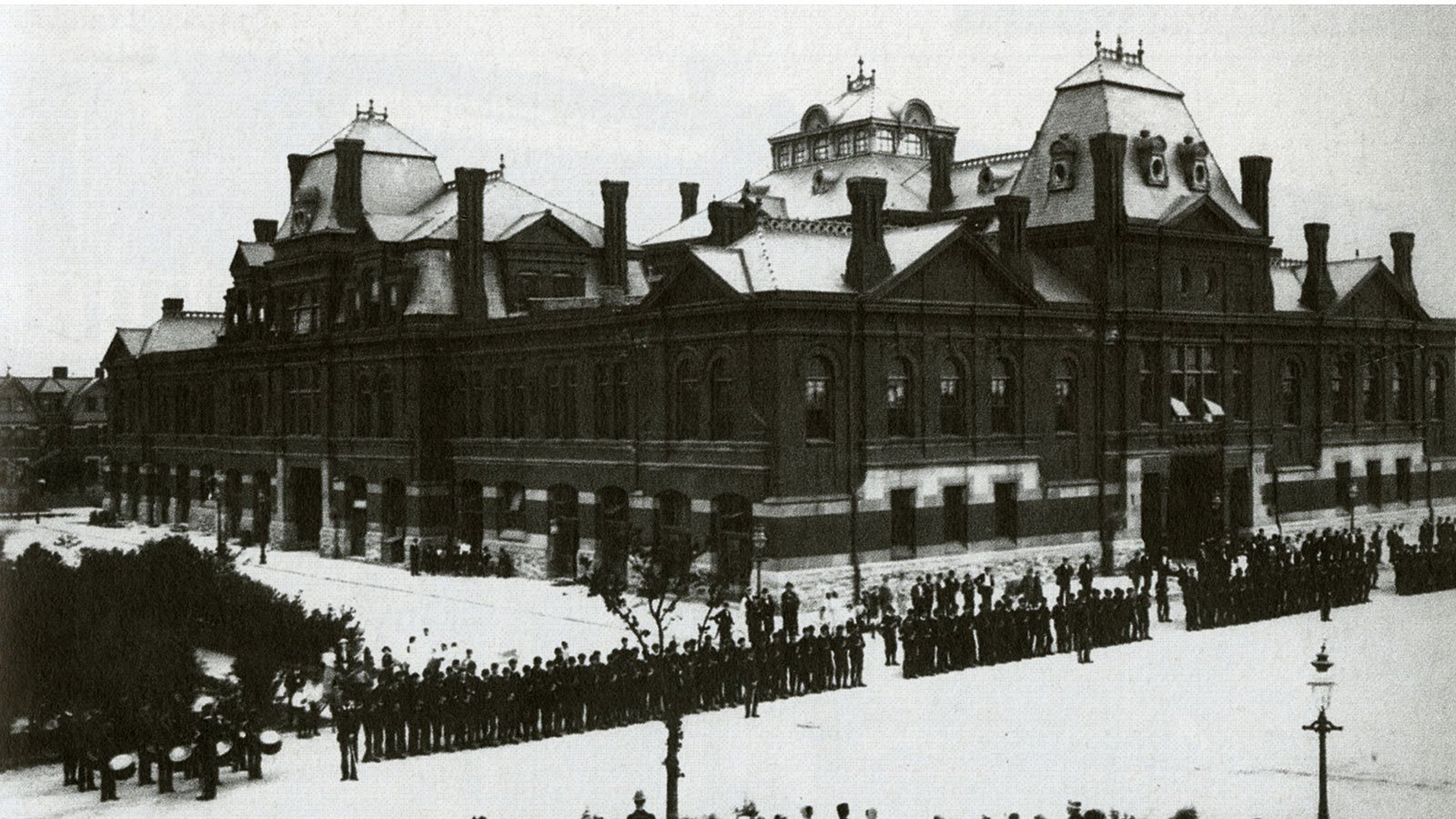

Pullman purchased 4,000 acres of land 14 miles south of Chicago and built both a new plant and a town with 531 houses for his workers. He called it Pullman.

George Pullman hired Chicago architect Solon Beman and landscape designer Nathan Barrett to create an orderly, clean, and park-like community, away from the chaotic city center. With its own hotel, library, theater, school, church, and shops, as well as an appealing variety of neat red brick homes, each with its own yard, Pullman offered residents everything he thought they could want.

It wasn't long before workers began to complain about the many rules governing life in Pullman, including a ban on alcohol sales (except to visitors staying at the hotel) and a dress code that dictated what they could wear outside of their homes.

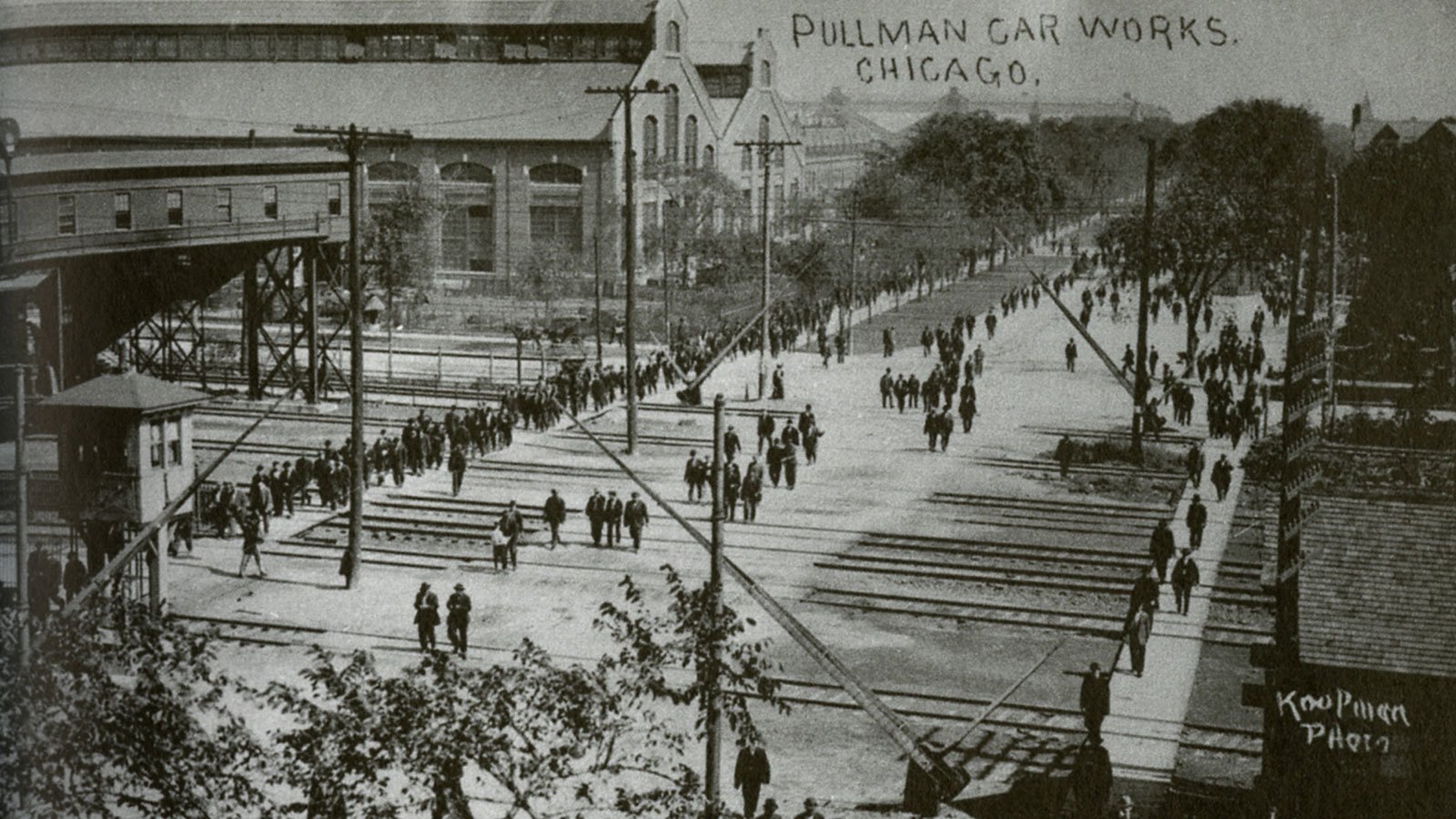

But the real breaking point came after an economic downturn in 1894, when George Pullman cut workers' wages by 25 percent but did not reduce their rents. That was a fatal mistake.

A walkout in May 1894 started out as an orderly demonstration, but grew into a series of violent conflicts that spread throughout the country and once again paralyzed rail commerce. Dozens were killed, and President Grover Cleveland sent troops to Pullman to restore order.

The unrest at Pullman inspired a national debate about workers' rights and the proper relationship between employer and labor. The conflict ultimately went to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ordered Pullman to sell either his plant or the town.

Pullman had lost control and ownership of a place that, for at least a short time, had served as a model for what a company town could aspire to be - in ideals if not in execution.