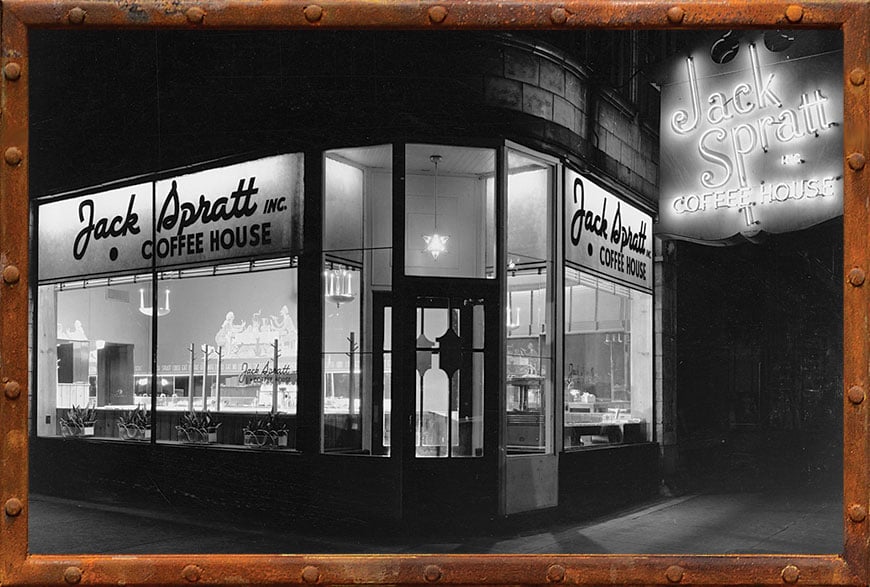

JACK SPRATT COFFEE SHOP SIT-IN

Kenwood

The Jack Spratt Coffee House on Chicago’s South Side played an early, unsung role in the civil rights movement. In 1942, it was the scene of one of the first nonviolent sit-ins, presaging the more celebrated lunch counter sit-ins that focused the nation’s attention on racial discrimination almost 20 years later. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

Watch the Segment

Recent Howard University graduate James Farmer stopped into the Jack Spratt Coffee House at 47th and Kimbark Avenue in Chicago’s Kenwood neighborhood with a friend to buy a donut. They were treated like second-class citizens. He came back with more friends and demanded equal treatment. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

One day in 1942, a young black man named James Farmer walked into a coffee shop at 47th Street and Kimbark Avenue to buy a donut. But the Jack Spratt counterman was unwilling to provide African Americans the same service that he gave to his white customers.

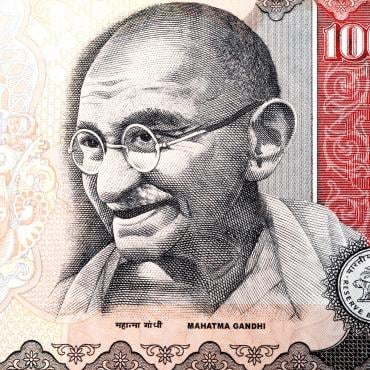

The counterman’s habit was to make African Americans wait; then he attempted to charge them a dollar for a donut that cost white people a nickel. What the counterman didn’t know was that Farmer, a recent graduate of the Howard University School of Religion, had been studying the philosophies and practices of Mahatma Gandhi – particularly his idea of creating change through nonviolent resistance. Farmer was ready to put those ideas into practice to stop racial discrimination in America.

Farmer came back with his friends and filled up the restaurant, demanding to be served. The manager called the police and asked to have them thrown out. But the police said there was nothing they could do. The coffee shop ultimately relented and served them, and Farmer and friends returned several times just to be sure they got the message.

Farmer was able to change the way Jack Spratt did business – almost twenty years before the famed lunch counter sit-ins of the civil rights era focused the nation’s attention on racial discrimination.

Farmer dedicated himself to ending racial segregation and discrimination. Soon after the Jack Spratt action, Farmer co-founded the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE), a national organization that would later organize Freedom Rides to desegregate interstate transportation. Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Farmer later risked his life by organizing protests in Louisiana in the 1960s and went to jail for disturbing the peace. “We will not stop until the dogs stop biting us in the South and the rats stop biting us in the North,'' he wrote. Photo Credit: Library of Congress

Farmer was inspired by the teachings of Mahatma Gandhi, who advocated nonviolent resistance. He had studied Gandhi’s philosophies as a theology student at Howard University. Photo Credit: Shutterstock

Farmer received the Presidential Medal of Honor from President Bill Clinton in 1998. He died in 1999. Photo Credit: Clinton Presidential Library