ROGERS AVENUE and CLARK STREET

Rogers Park

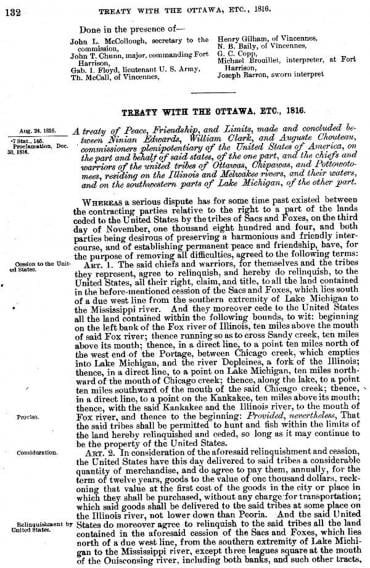

In 1833, 160 years after the explorations of Marquette and Joliet, Native Americans signed away all rights to their land east of the Mississippi River in the Treaty of Chicago. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

Indian Treaties

Watch the Segment

In the Treaty of 1816, the Fox and Sauk ceded an area from Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River, with northern and southern boundaries designed to allow for the Illinois and Michigan Canal to proceed. The Native Americans were allowed to hunt and fish “so long as it may continue to be the property of the United States.” Photo Credit: Public Domain

LEARN MORE

Read about Chicago as a crossroads of trade.

Read about Metropolitan Chicago's topography.

View a map and read about the Chicago area before humans inhabited the land.

For decades, European explorers, traders, and settlers, especially the French, came to this area and traded with the Native Americans who called this territory home. Helpful natives showed Marquette and Joliet where the Chicago portage could be found; such early Chicagoans as Jean-Baptiste Point de Sable and Gurdon Hubbard often married Native American women.

With some notable exceptions, the natives and the newcomers lived side by side in a mostly symbiotic arrangement – for a while.

But they say that no good deed goes unpunished, and by showing Marquette and Joliet the Chicago portage, those friendly Native Americans inadvertently paved the way for their own demise.

In order to make way for the Illinois and Michigan Canal, Governor Ninian Edwards and others negotiated the 1816 Treaty of St. Louis to acquire land from the Great Lakes all the way to the Mississippi. Rogers Avenue in Rogers Park forms part of this boundary, and a small plaque can be found at the northeast corner of Rogers Avenue and Clark Street.

The actual treaty document describes the land the Native Americans gave up so that the newcomers could build their canal:

The said chiefs and warriors, for themselves and the tribes they represent, agree to relinquish, and hereby do relinquish, to the United States, all their right, claim, and title, to all the land contained in the before-mentioned cession of the Sacs and Foxes, which lies south of a due west line from the southern extremity of Lake Michigan to the Mississippi river. And they moreover cede to the United States all the land contained within the following bounds, to wit: beginning on the left bank of the Fox river of Illinois, ten miles above the mouth of said Fox river; thence running so as to cross Sandy creek, ten miles above its mouth; thence, in a direct line, to a point ten miles north of the west end of the Portage, between Chicago creek, which empties into Lake Michigan, and the river Depleines, a fork of the Illinois; thence, in a direct line, to a point on Lake Michigan, ten miles northward of the mouth of Chicago creek; thence, along the lake, to a point ten miles southward of the mouth of the said Chicago creek; thence, in a direct line, to a point on the Kankakee, ten miles above its mouth; thence, with the said Kankakee and the Illinois river, to the mouth of Fox river, and thence to the beginning: Provided, nevertheless, That the said tribes shall be permitted to hunt and fish within the limits of the land hereby relinquished and ceded, so long as it may continue to be the property of the United States.

Many of the chiefs and warriors signed the treaty with an “X”; one wonders whether they fully understood what the treaty would mean, given that they were told they could continue to hunt and fish there forever.

But what happened next was very clear: In 1830, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act, and in 1833, in the coup de grace, local Potawatomi gave up the last of their lands here, agreeing to leave the Chicago area completely and move west of the Mississippi.

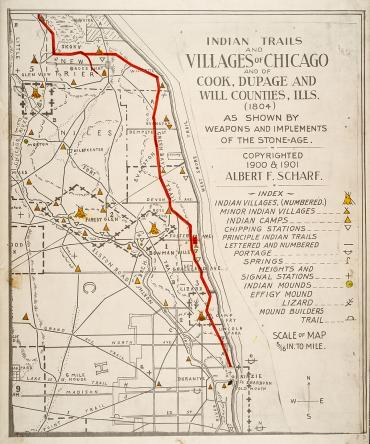

Indian Trails

The Native Americans trails from those pre-1833 days – which can also be found in some of the diagonal streets that cross our otherwise rectilinear street grid (Clark Street, for example) – reveal a natural topography, and also a bit of geological history.

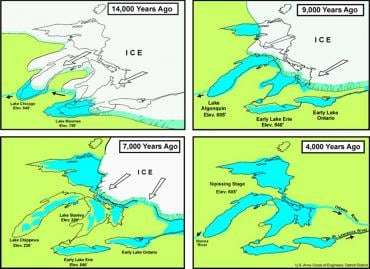

Ridge Avenue, for example, traces the path of a natural ridge created by the shoreline of a prehistoric lake – Lake Chicago, which formed in the wake of the melting glaciers and predated Lake Michigan.

As a result, Ridge Avenue is significantly elevated above the current Lake Michigan shoreline – up to 40 feet higher in some places, though the incline is very subtle. Native Americans made use of this natural high ground as they navigated across wet terrain on foot.

And the next time you’re wondering why Chicago is so flat, just keep in mind that we used to be on the bottom of a very large lake.

Native American trails prior to 1833 days reveal the natural topography of the area, which was created entirely by glaciers. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

Lake Chicago formed when the glaciers melted at the end of the last Ice Age. Native Americans followed trails formed by the natural ridges left by shorelines and other features; today, we can see the traces of those trails in the diagonal streets on our street grid – such as Clark Street and Ridge Avenue. Photo Credit: Public Domain

A plaque at Rogers Avenue and Clark Street commemorates the 1816 Treaty of St. Louis, in which Native Americans ceded land from the Great Lakes all the way to the Mississippi. Photo Credit: Alan Brunettin

The plaque is difficult to view. Photo Credit: Alan Brunettin