A Coyote Comeback | Chicago

Coyotes have made a remarkable comeback in Chicago. What are the secrets to their survival in a dense metropolis? We hunted for clues with noted biologist Stan Gehrt.

Pursuing a radio-collared coyote by foot, Stan Gehrt loses a fading signal from his handheld antenna.

The elusive predator seems to know that Gehrt is on its tail. With the coyote on the run along a Chicago railroad embankment, Gehrt does not give up. He joins his team in a nearby antenna-mounted pickup truck and they hit the road in hot pursuit. Gehrt’s team optimistically takes turns spinning the antenna’s cabin contraption for frequencies until they finally corner the coyote.

This coyote is no stranger to this team of researchers. Gehrt’s team knows her as coyote 977, an adult alpha female they captured and collared in February 2016.

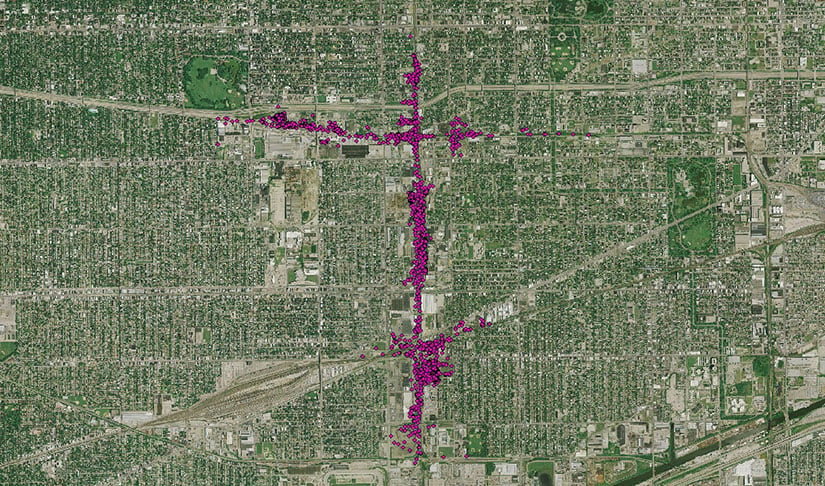

Gehrt has been studying the behavioral patterns of urban coyotes for 16 years. As the chair of research at the Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation, Gehrt established the Cook County Urban Coyote Project in 2000 and serves as the project’s principal investigator. Using radio collars and infrared cameras, Gehrt and his team track coyotes across the entire Chicago metropolitan area and analyze how these predators are surviving on city turf.

Coyotes have just recently returned to Chicago after a long absence. As the city grew from a frontier town to a booming urban metropolis in the 19th and 20th centuries, native coyotes were forced out. But over the past 20 years, expanding rural and suburban coyote populations pushed the species back into dense urban habitats.

Studies have shown that coyotes have a higher survival rate in Chicago compared to its surrounding rural areas. In rural areas, coyotes are threatened by hunting and trapping, and during the fall crop harvest the species loses habitat. Large metropolitan areas provide coyotes with better habitat protection year-round.

In rural areas, coyotes are active at all times of the day. As coyotes have made their way into city neighborhoods, they have adapted to become active at night, which allows them to avoid human contact.

Since urban coyotes are nocturnal, Gehrt’s team has to work 24-7 to track the creatures down. When the team captures a coyote, they transport the animal to their suburban lab at the Max McGraw Wildlife Foundation, where the coyotes are given an overall health evaluation. Once at the lab, a “hand” test is administered, in which the team pokes a rubber hand at the coyote, and records its behavior. The data allows Gehrt’s team to create a personality profile of each animal. According to Gehrt, most coyotes react submissively to the hand test.

The team also takes a blood sample at the lab to test for genetics and disease, and plucks whiskers to determine what the animal has been eating. Each coyote whisker holds four to five months’ worth of chemical evidence of the animal’s diet. Gehrt is particularly interested in whether the coyote has been eating a natural diet, or relying on human food. According to Gehrt, a recently conducted diet analysis shows that Chicago coyotes eat a split of human and natural foods. Gaining a better understanding of an urban coyote’s diet can also provide hints about its behavior and personality.

“Our ultimate goal here is to determine whether or not life in the city selects for a certain type of personality trait,” Gehrt said.

So far, the team’s research indicates that there is no one single type of coyote, which is one reason Gehrt believes coyotes have been able to adapt successfully in dense cities.

Before coyotes are released back into the wild, a radio collar is attached that allows the team to identify and monitor where the coyotes are traveling. With the data from the project, Gehrt’s team hopes to educate the public about the coexistence of coyotes and people in the city. While some people may fear a face-to-face run-in with a coyote in their backyard, Gehrt said that coyotes are actually more frightened by people and that it is important to understand that attacks by coyotes are extremely rare.

Additionally, Gehrt stressed that the threats the animals may pose are far outweighed by the ecological benefits to urban landscapes, including rodent control.

“Urban systems need predators,” Gehrt said. “The biggest thing to do to help them, is not help them.”

— Sean Keenehan