You say Chi-CAH-go. I say Chi-CAW-go. But how do we really pronounce the name of our city, and where does the name come from? When it comes to the name of the biggest city in the Midwest, the answer is a rich Indigenous linguistic history.

Before European explorers such as Jacques Marquette and Louis Jolliet first came to what is now Chicago in the late seventeenth century, Indigenous peoples such as the Ojibwe, Odawa, Potawatomi, and many others populated the region. These nations spoke the languages that were part of the Algonquian language family.

“Most native people during this period would’ve been multilingual,” Rose Miron, director of the D’Arcy McNickle Center for American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the Newberry Library, told Geoffrey Baer in a Chicago Mysteries interview. “[Algonquian] languages are related similarly to how we would think about Spanish and Italian and English being related languages…They are more distinct than different dialects of the same language.”

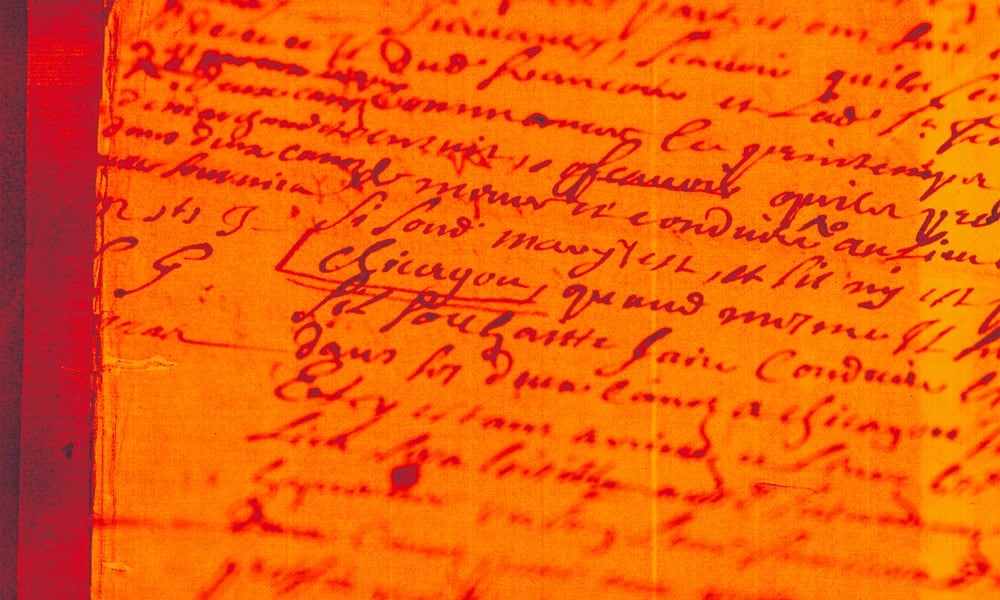

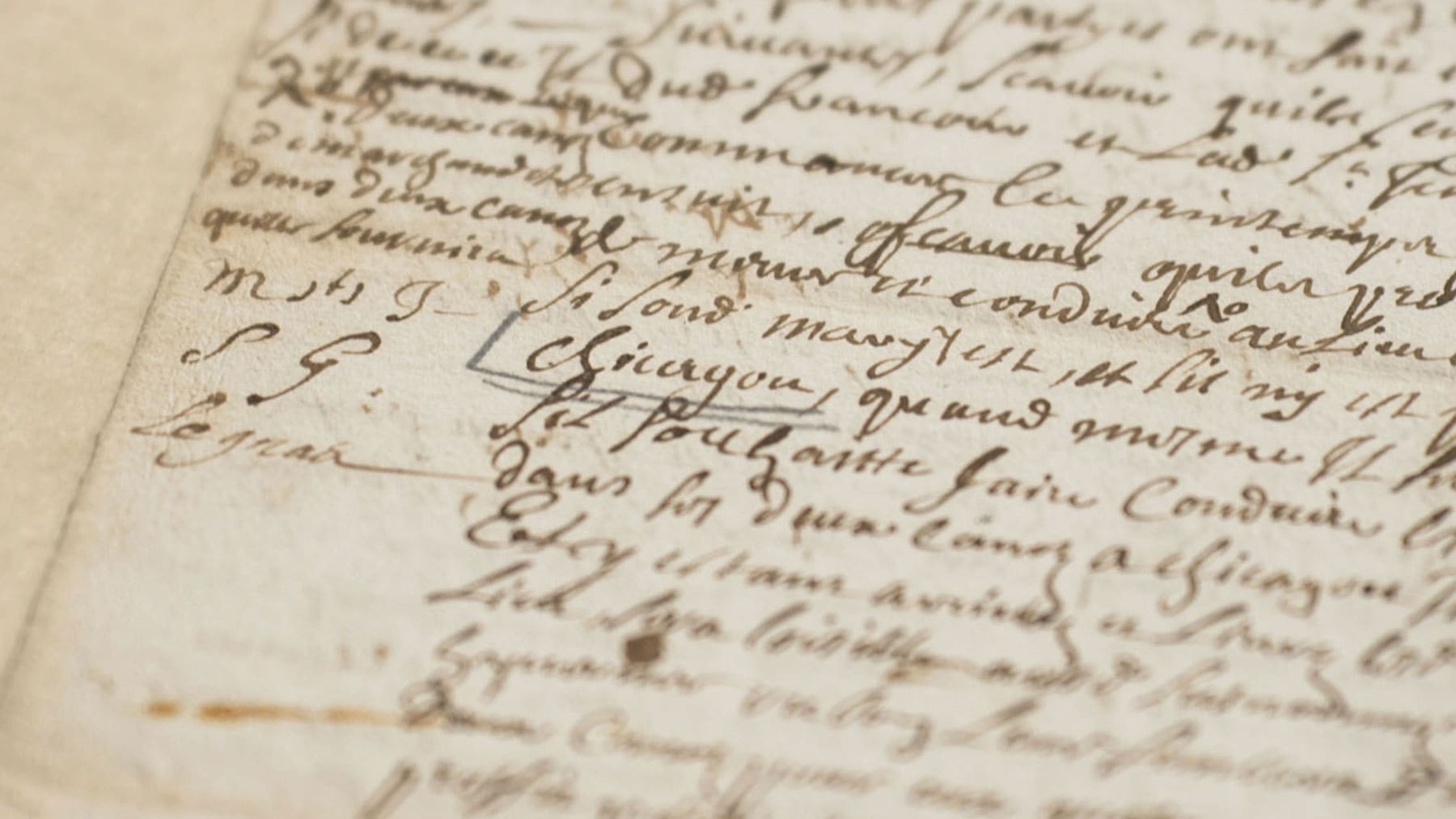

It was these languages that gave Chicago its name. In the collections of the Newberry Library, the earliest document that mentions Chicago by name dates back to 1692, 145 years before Chicago was incorporated as a city. The name appears in a fur-trading contract, and it is spelled “Chicagou.”

In this document, which comes from Quebec, “We are seeing Chicago as an important place where many people are coming to meet – all tribal peoples and nations, but also settlers,” said Analú López, the Ayer Librarian and Assistant Curator of American Indian and Indigenous Studies at the Newberry Library.

That unexpected “u” at the end of “Chicagou” was likely a French addition and an interpretation of the Indigenous words for Chicago. Each language had a slightly different meaning. Some are closer to skunk, while others refer to the fragrant wild onions, leeks, or ramps that flourished in the area. “I think what the words have in common is a strong scent,” Miron said. For example, the Potowatomi variation, zhegagoynak, means “place of wild onion,” while the Ojibwe word, zhigaagong, means “on the skunk.”

“I don't believe that there is any one way to pronounce Chicago,” Indigenous educator Starla Thompson said. “There are many nations that lived here and prospered, and they all have their interpretations.”

Here are some of the interpretations:

- Potawatomi: zhegagoynak

- Ojibwe: zhigaagong, or gaa-zhigaagwanzhikaag

- Odawa: zaagawaang or zhigaagoong

- Myaamia and Illinois: šikaakonki

- Menominee: sekākoh

- Sauk: shekâkôheki

- Ho-Chunk (not in the Algonquian language family): gųųšge honąk

Something that is important to note: “Spellings of Native words sometimes vary,” Miron said. “Just like there are many dialects of English, there are frequently several dialects of Native languages that result in multiple spellings.”

In addition, native languages were never even meant to be written down. But when Europeans colonized the region, made contact with these languages, and then attempted to write them down, they may have been trying to transcribe sounds that didn’t even exist in their own language.

“They are oral languages,” López said. “Once you start writing them down, there are certain words or sounds that can’t be interpreted, so then [they] could possibly be mishearing something and writing it down as the closest thing that exists in [their] language.”