In 1982, seven deaths forever changed Americans’ sense of consumer safety. After someone poisoned Tylenol capsules with lethal doses of cyanide and placed them on store shelves where unsuspecting customers purchased them, Chicago – and the rest of the country – was rattled with a newfound realization that the products in their medicine cabinets may not be as safe as previously thought. Though the mystery remains as to who poisoned the capsules and why, one particular suspect emerged and remained on investigators’ radar for decades. To gain insight into one of Chicago’s most enduring and haunting mysteries, Geoffrey Baer interviewed as part of Chicago Mysteries a local reporter, a public health official, and an assistant U.S. attorney who investigated the case and prosecuted the prime suspect, albeit on a lesser charge.

Public Panic

When a 12-year-old girl in Elk Grove Village wasn’t feeling well on September 28, 1982, she took an Extra-Strength Tylenol capsule. She was hospitalized after getting much sicker, and she died the next day. Over the next three days, six more people – all of whom were in their 20s and 30s and three of whom were from the same family – died. They were all otherwise healthy, and they had all taken Extra-Strength Tylenol. A public health nurse quickly linked the deaths to Tylenol, possibly saving many other lives.

Six of the deaths occurred in the northwest and western suburbs, and one woman died in the city of Chicago. WLS reporter Chuck Goudie was assigned to cover the story in Arlington Heights. Goudie told Geoffrey Baer in a Chicago Mysteries interview that one particular memory from reporting in those first few days stands out.

“All of a sudden, as the sun is setting, you have ambulances and police cars cruising through the neighborhoods with their loudspeakers warning people that if they have Tylenol in their bathrooms, don’t take it…The authorities had no clue what they were dealing with.”Chuck Goudie, WLS reporter

Investigators determined that the bottles the victims had used were tainted with lethal amounts of cyanide. Part of what made the deaths so frightening to the public, said Goudie, was that there was no pattern that suggested particular individuals were targeted. It was entirely, terrifyingly random. On October 5, Johnson & Johnson, which manufactures Tylenol, issued a recall of 31 million bottles and halted production at a cost of $100 million. Authorities discovered that the capsules had been manufactured in different locations. That led them to the conclusion that someone had removed the pills from store shelves, pulled apart the gelatin capsules to fill them with cyanide, reassembled the packaging, and then placed the poisoned pills back on the shelves.

“I went through my kitchen cabinet. I went through the bathroom cabinets, but it’s not so much looking for Tylenol as it was not knowing what else I should look for,” Jeremy Margolis told Baer in an interview. Margolis served as the assistant U.S. attorney during the time of the Tylenol murders and worked on the case. “Back in those days, there was no such thing as tamper-proof packaging.”

Michael Petros worked in a laboratory for the Chicago Department of Health that was tasked with looking through thousands of bottles and an estimated 80,000 individual capsules of Tylenol to look for cyanide. At the time, there was no chemical test for cyanide; the lab staff had to visually inspect each capsule.

“What we were looking for were these heavy crystals – almost like rock salt, but a little bit smaller – that were put in those capsules because, at the time, they could be just pulled apart,” Petros told Baer. While Petros’s team did not test any of the bottles associated with the murders, someone else in the same facility did find another poisoned bottle.

“It came from a store near where the Chicago fatality occurred. So as soon as that was found, we notified our lab director, who notified law enforcement and they collected that right away,” Petros said. “I never looked at the over-the-counter medicines at the stores the same way.”

The Tylenol murders marked a change of tide. It was a massive news story.

“Our newscasts were wall to wall with this story, and rightly so. You had a number of people dead and almost every question unanswered,” Goudie said. “It was, to be trite, an all-hands-on-deck situation not only for law enforcement, but for news organizations.”

For law enforcement, there was one key question: Who would commit a crime like this and why?

The Suspect That Stood Out

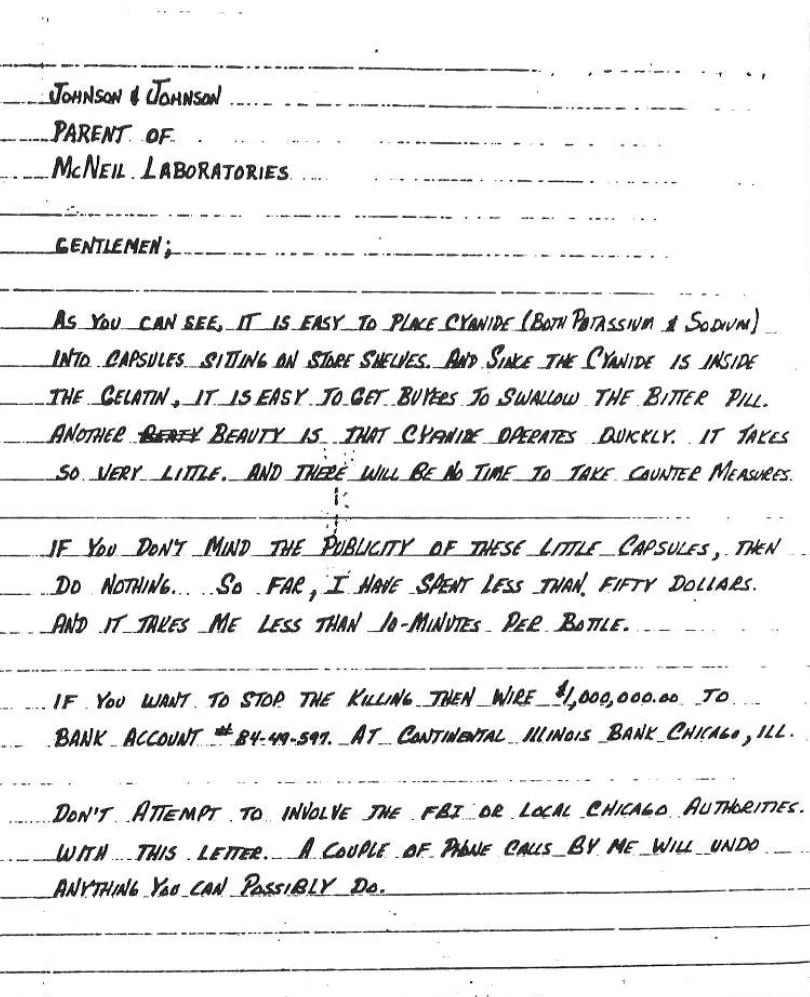

As a task force of local police, state police, and the FBI took on the case, Johnson & Johnson and the White House received letters from someone demanding $1 million to stop the murders.

“I was elated that we got…an investigative break. I mean, to have a piece of paper, an original piece of paper with information on it, it was like manna from heaven. We were thrilled,” Margolis said.

Investigators eventually traced the letters back to a man named James William Lewis, who had used his former employer’s postage meters to send the notes. Using coded messages in advertisements placed in the Chicago Tribune, investigators, posing as the recipients of Lewis’ letters, covertly communicated with their suspect, whom they believed to be in New York. “FBI agents went to every single location in the five boroughs where one could obtain the Tribune,” Margolis said. “Some were under surveillance. Others, like libraries, were visited, contacted, and the librarians interviewed and put on notice.” When a librarian spotted Lewis, she contacted police, and he was arrested.

Lewis denied – and would continue to deny – that he was the one who poisoned the Tylenol capsules. But he admitted to writing the letters. He claimed he sent them to draw the police’s attention to his former boss, who bounced his paychecks. Lewis claimed that “he waited for the first national tragedy to occur that he could use to put an investigative spotlight on” the employer, Margolis said. They also discovered Lewis had a violent criminal past. Four years prior, he was charged with killing and dismembering a man whom Lewis had hired as an accountant. He tried to cash a check forged in the victim’s name. However, despite compelling evidence of his guilt, a judge dismissed the case because Lewis had not been read his Miranda rights upon arrest.

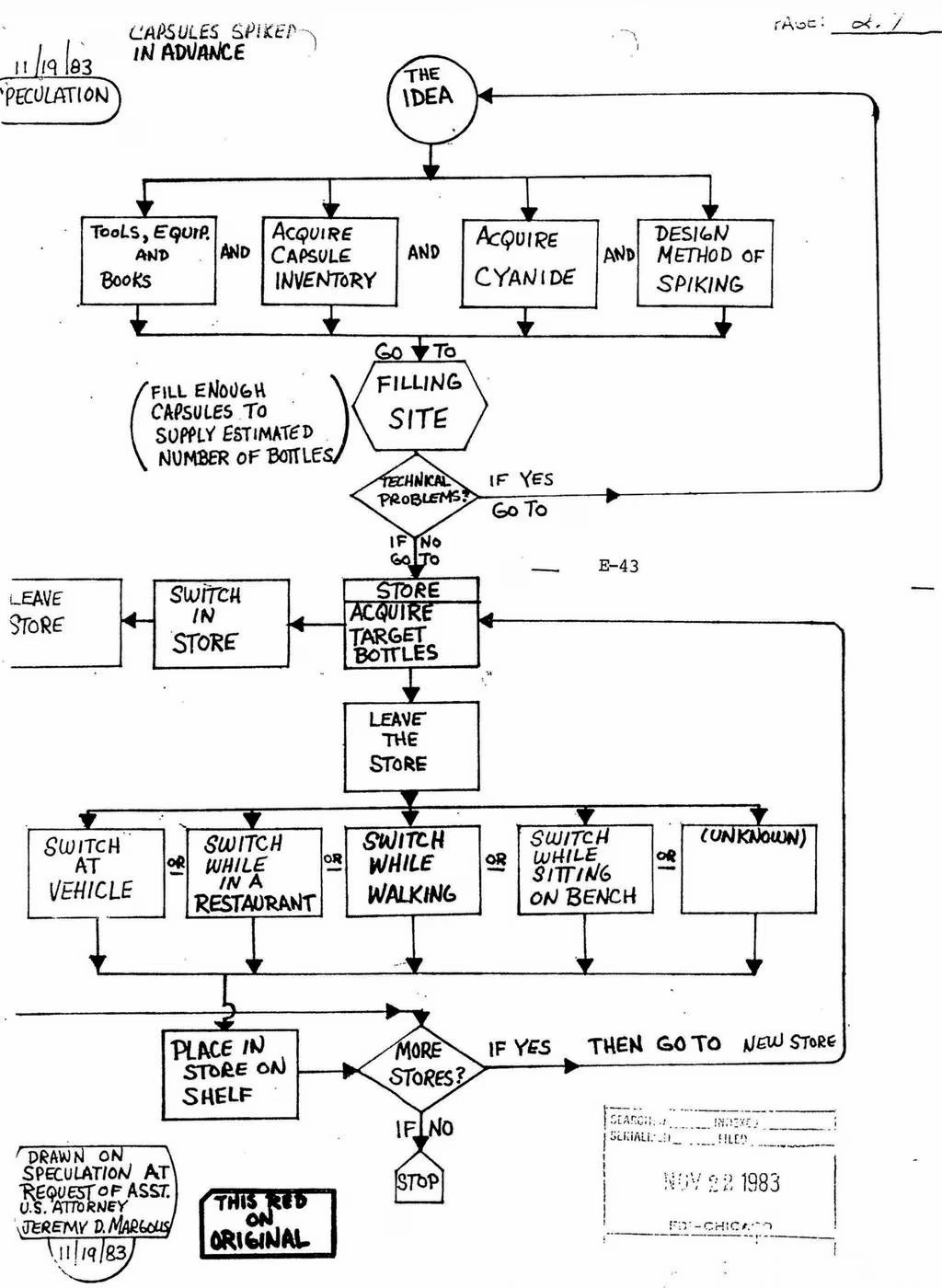

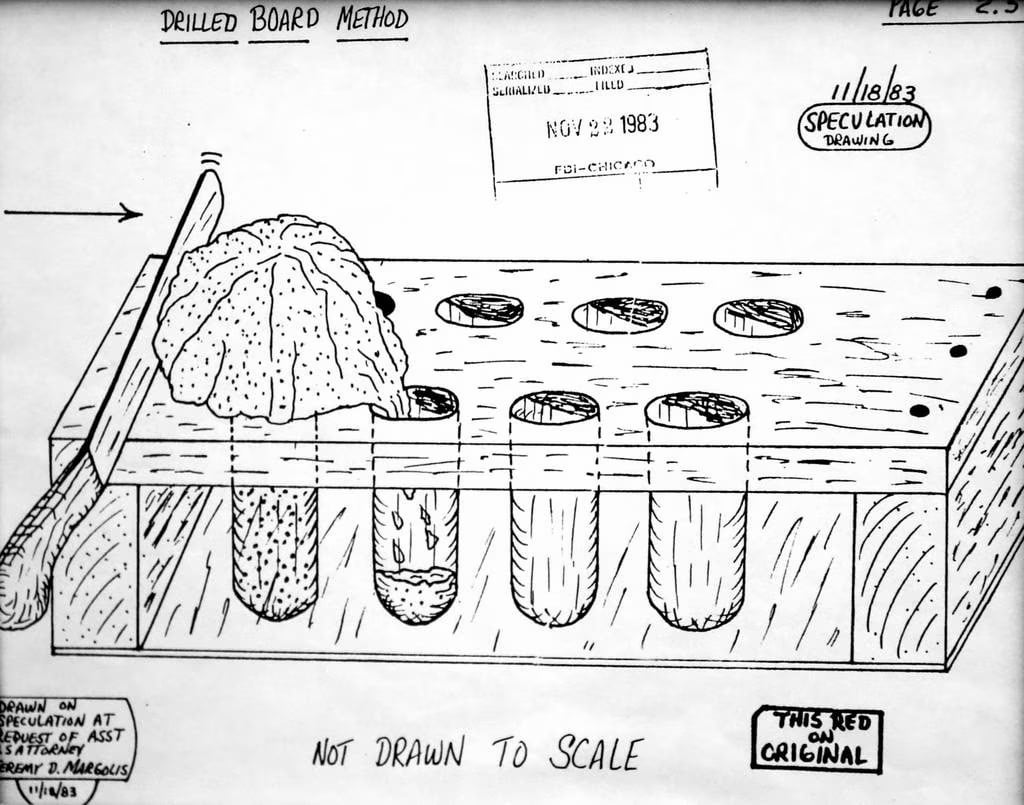

Further raising suspicion, Lewis offered during his police interviews to “help” investigators by providing detailed theories, drawings, diagrams, and manuscripts as to how the murderer may have gone about filling the capsules and distributing them.

Margolis said he and his fellow investigator were “thunderstruck by the specificity” of the drawings, and the “many, many hours of painstaking work” that it would have taken him to prepare the materials. He found Lewis to be “arrogant, haughty, [and] condescending.”

“It was nothing short of bizarre. Here’s a guy who is facing many years in the federal penitentiary, publicly accused although not formally charged with the Tylenol murders, who volunteers his assistance to law enforcement to help them solve the Tylenol murders, and then provided us with dozens and dozens and dozens of pages of manuscripts speculating on how it might’ve happened.”Jeremy Margolis, former assistant U.S. attorney

Goudie interviewed Lewis over the years and said the suspect appeared to enjoy the cat-and-mouse game with authorities and journalists. “James Lewis was one of those criminals who thought that he was the smartest guy in the room,” Goudie said. He sometimes received phone calls from Lewis. “He would call me angry about stories that we aired, didn't like that we presumed he was the Tylenol killer, even though he put himself right in the middle of it and explained the entire series of attacks.”

Due to a lack of evidence, Lewis was never charged with the Tylenol murders. He was tried and convicted for extortion for writing the letters to Johnson & Johnson and the White House and served 10 years in prison. Separately, in 2004, he was charged with rape and kidnapping and awaited trial in jail for three years, but the charges were dropped when the victim would not testify. In 2010, he self-published a novel about people drinking lead-poisoned water called, Poison! The Doctor’s Dilemma, which directly references the Tylenol murders, per one NBC Chicago report at the time. After his release from prison, Lewis moved to Boston, where he died of natural causes in 2023 at age 76.

“I thought Lewis was a serial criminal,” Margolis said. “It would’ve been just had he died in jail. But I still don’t speculate on whether he was the Tylenol killer or not.”

The case remains unsolved, though it never closed. Authorities have continued to investigate the murders, including collecting DNA samples from Lewis in recent years. Investigators did pursue other suspects in the weeks and years after the Tylenol murders. A man who worked at a Jewel in Melrose Park, was considered a suspect, but DNA evidence from his exhumed body did not match DNA found on the Tylenol bottles, according to the Chicago Tribune.

Consumer Safety Improvements

The Tylenol murders forever altered the sense of consumer safety around packaged medication and other products. “This case changed all sorts of habits, from packaging, to the way people take drugs, to what they do and think about when they go into a store and whether something has been opened or not,” Goudie said.

Over the next several months and years, local governments and federal agencies worked to reestablish consumer confidence, which was particularly important, as other incidents apparently attempted to repeat the Tylenol killer’s method.

“There were some 200 or so copycat incidents in the years afterwards, with a number of people killed,” Margolis said.

In the aftermath of the murders, Johnson & Johnson acted quickly. In addition to their recall, the company redesigned their bottles to include a foil seal, and introduced a solid “caplet” that was more difficult to tamper with. The Cook County Board of Commissioners also passed an ordinance just days after the murders “requiring some sort of seal, in addition to a lid or cap, on all nonprescription medicines and drugs sold in Cook County,” per a front page article in the Chicago Tribune on October 5, 1982. In 1983, Congress passed a law making it a federal crime to tamper with food, drugs, cosmetics, and other products. In 1989, the Food and Drug Administration enacted federal guidelines for tamper-proof packaging.

When Lewis died in 2023, headlines across media outlets cited him as the prime suspect. Despite the lack of evidence at the time of the murders, Margolis thinks it’s still possible that the public will get answers. “To the extent that investigative files become public record and public knowledge, I think people will be able to draw fair conclusions as to what the evidence suggests,” he said.

Goudie takes it a step further: “There is some degree of consensus, I think, and satisfaction at least that when James Lewis died, the Tylenol killer died,” he said.

Officially, however, the identity of the Tylenol murderer remains a mystery.