Before he was released from prison, Bob Covelli told everyone he knew the three things he wanted most once he got out: a job, an apartment, and a kitten. “I’m less anxious, and I’m less angry when I hear a cat purring,” he said in an interview.

Covelli was incarcerated for almost 40 years for a 1982 robbery and murder of an Elmhurst jewelry store owner. He was diagnosed with anxiety and bipolar disorder in prison, which he said helped him understand his behavior.

“I didn’t know I was experiencing manic episodes when I was stealing,” he said. “I just thought it was ‘magic time’ — that no one could stop me.”

While incarcerated, Covelli became a published poet and cartoonist, calling attention to the plight of his fellow prisoners. He got a job as a custodian, throwing out the trash, cleaning cells, and mopping up the floors. He figured he could find similar work once he was out, and the rest of his life would follow after that.

But a year and a half after leaving prison, the 68-year-old is unemployed and living at a homeless shelter — “the only place left open to me,” he said.

“The way I’m living right now, I call it pretend freedom.”

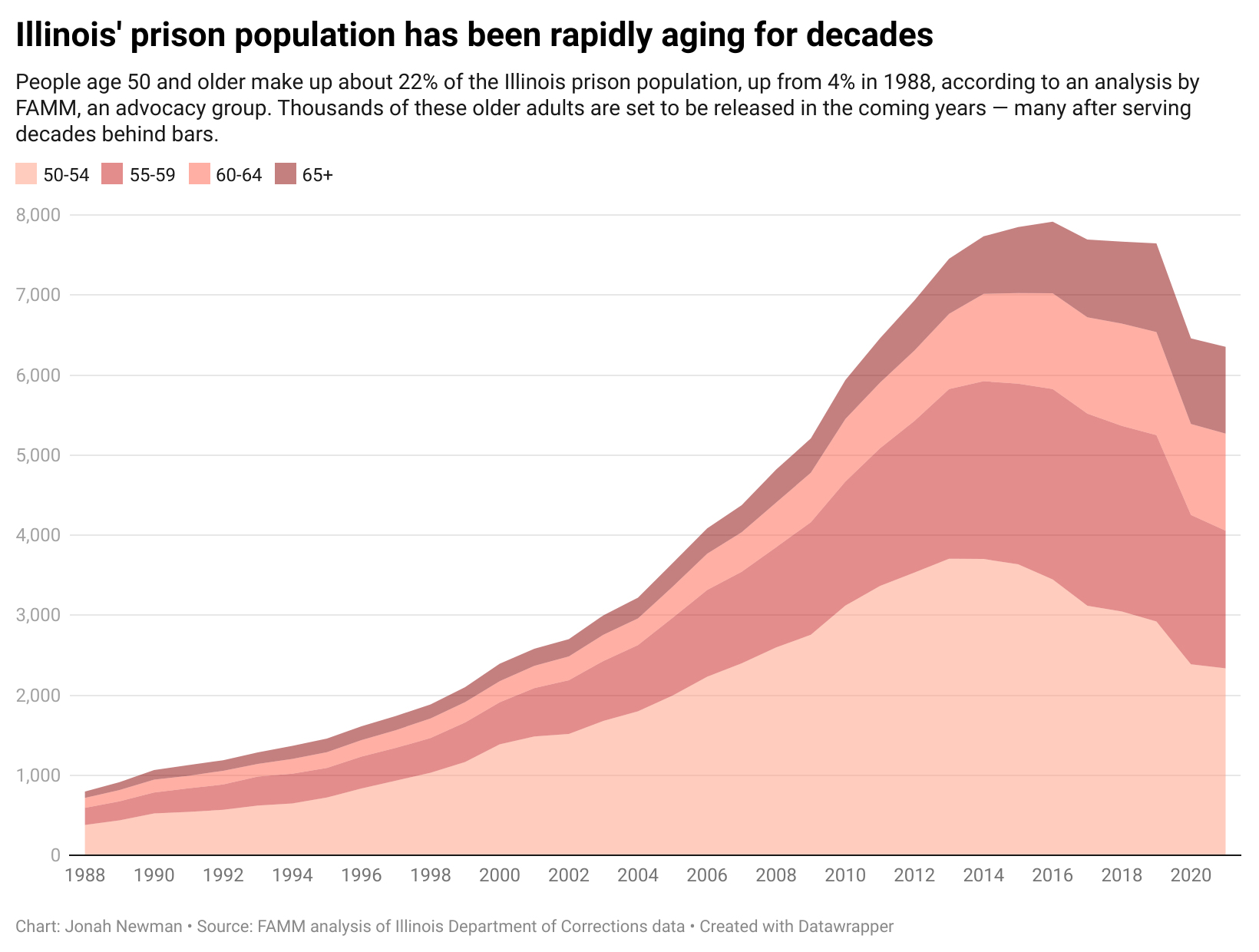

Covelli is one of at least 17,000 adults age 50 and older released from Illinois prisons since 2014, according to an Injustice Watch estimate based on state corrections data. And thousands more older adults are expected to come out in the coming years, many of whom were given long sentences at the height of the “tough-on-crime” era of the 1980s and ’90s.

Nearly 10,000 people incarcerated at the end of last year — roughly one-third of the prison population — will be age 50 or older when they are projected to be released. More than half of them are Black, and many will have served decades behind bars.

Older adults coming out of prison face unique challenges on top of the social stigma facing all former prisoners, experts say. Many end up homeless and unemployed, and their criminal records can sometimes block them from accessing safety net programs meant to prevent older adults from falling into poverty.

Many come out with chronic illnesses and disabilities, but they can be turned away from nursing homes and other long-term care facilities, leaving their families — if they have any left — to pick up the slack.

Criminal justice reform advocates want state lawmakers to allow more incarcerated older adults to get out early, so they can have a better chance at building a stable life after prison, especially because older adults are less likely to reoffend than their younger counterparts.

“We chose as a society to hand out these really crazy sentences — focusing specifically on Black and brown men — for several decades, and our answer to that is we just want to throw you away, and you just have to figure it out,” said Avalon Betts-Gaston, project manager for the Illinois Alliance for Reentry and Justice, a coalition of legal aid and direct-service organizations.

Pathways for an early release in Illinois are limited. Approximately only three dozen people have been ordered released under a law enacted last year to create a path to parole for prisoners with terminal illnesses and those who are medically incapacitated. Another measure to open parole to elderly prisoners who’ve served at least 25 years has stalled in the state Legislature.

When they get out, older adults often confront a world that feels completely foreign, Betts-Gaston said.

“When they went in, things were drastically different in every aspect of life than they are right now, and we don’t have any systems in place to prepare them for that,” she said.

Betts-Gaston and a half-dozen other advocates and experts interviewed by Injustice Watch said local, state, and federal lawmakers should put more resources into supporting older adults upon reentry.

Otherwise, some older adults could end up like Covelli, wishing they were back in prison.

“At least in there, I felt respected for who I am,” he said. “Out here, I do everything that’s asked of me, but it never feels like enough.”

Older adults struggle with jobs, housing after prison

Last fall, after submitting two dozen job applications with no luck, Covelli was finally hired as a custodian at an industrial bakery in the suburbs. It took him two buses and sometimes more than an hour to get there from the South Side shelter where he lives.

But after only a few weeks at the job, Covelli said he felt a sharp pain in his back after he tripped on a folded carpet in one of the offices he was cleaning, triggering sciatic nerve problems that he developed in prison.

Afraid of falling again, Covelli stopped going to work until the pain dissipated. But by then, he said they stopped answering his emails.

Covelli hasn’t been able to find work ever since, despite practically begging for a job. “I am willing to work construction or remodeling for a week for free,” he said.

Now, he also faces losing his spot at the shelter.

“This shelter is only for one year. My year was up on May 1,” he said. “No one has said I have to leave, but no one has tried to help me get housing, either.

“I keep waiting for the third shoe to drop.”

Covelli’s struggles illustrate how formerly incarcerated older adults often have a hard time finding long-term work and housing.

A recent study by the U.S. Department of Justice found 60% of former federal prisoners age 55 and older were unemployed four years after their release, compared to 31% of those younger than 55. It’s estimated that former prisoners age 45 and older are 12 times more likely to be homeless than the general public.

Researchers say formerly incarcerated older adults often face discrimination based on the stigma against people with criminal records, as well as the prevalence of everyday discrimination against older adults.

TJ Wendle, a community outreach specialist for the Reentry Support Institute at Roosevelt University in Chicago, said many of the more physically demanding jobs open to people with criminal records, such as working in “warehouses or back-of-house of a kitchen or janitorial things (are) jobs that somebody in their advanced age might have more difficulty with.”

Complicating the reentry journey for many older adults is their often-precarious health, which can make finding a job and housing more difficult. Research shows that living in prison deteriorates a person’s health more quickly because of the stressful and dangerous environment and lack of access to nutritional foods and quality health care.

More than 57% of state prisoners age 55 and older surveyed for a recent report from the Justice Department reported having a disability — a rate three times higher than general public — and more than 80% said they had at least one chronic illness. In Illinois, the prison health care system has for years failed to meet the most basic standards of care, especially for elderly prisoners and prisoners with disabilities, according to recent reports from a court-appointed monitor.

These chronic illnesses and mobility issues make finding adequate housing even more challenging, said Michael Stone, legal director of the Center for Disability and Elder Law, a pro bono firm in Chicago.

“Affordable housing stock tends to be older, and older housing stock also tends to be less accessible,” Stone said.

Many of the state’s halfway houses are also inaccessible to people coming out of prison with disabilities, said Ashley Bishel, a staff attorney at the Uptown People’s Law Center, a Chicago-based civil rights organization that represents current and former Illinois prisoners. And because they can’t find an approved host site that meets their mobility needs, some disabled older adults end up staying in prison while they’re on parole “when they were supposed to be out in the community,” she said.

The Illinois Department of Corrections did not make officials available for an interview. A spokesperson for the department acknowledged in a statement the “small number” of beds at halfway houses deemed accessible under the American with Disabilities Act but said the decision about who to admit is up to the reentry facilities.

“While important, ADA accessibility and needs are not the only thing that vendors may consider when reviewing referrals from IDOC,” the spokesperson said.

It’s even more complicated for returning citizens who need to access nursing homes or other long-term care facilities, said Dr. Michelle Gittler, medical director at Schwab Rehabilitation Hospital in Chicago, which serves current and former Illinois prisoners.

“There’s no law that says someone with a criminal [conviction] cannot go to a nursing home, but the nursing homes have created a paradigm that says they’re not taking them,” Gittler said.

State law requires nursing homes to conduct criminal background checks on residents and allows them to deny entry to someone based on their criminal conviction. Gittler said sex offenders are particularly difficult to place in long-term care facilities.

“Anybody with any history of being a child predator or sexual offender will never get into a nursing home,” she said. “Even if they had bilateral strokes — can’t move their arms, can’t move their legs — and are clearly not able to do any harm, they won’t get in.”

It’s not clear how many returning citizens in Illinois need nursing care when they are released. Under state law, IDOC is required to report data to the state Legislature on the type of housing facilities where people live upon their release. In its most recent reports to legislators, however, the department says it doesn’t know where the majority of people are living, and nursing homes or long-term care facilities are not one of the options listed.

A spokesperson for the department did not respond to a request for comment about the data.

Long sentences make reentry more difficult

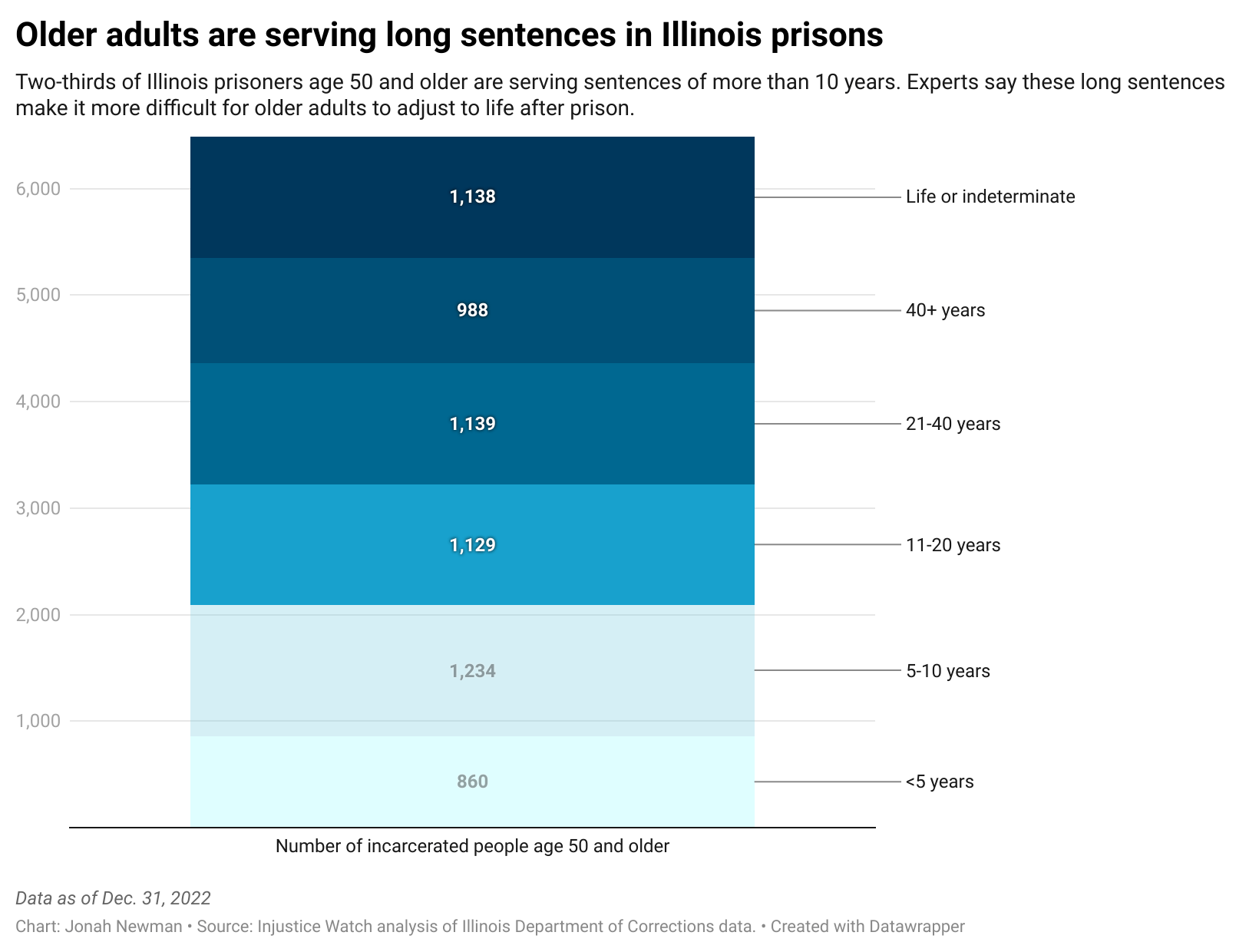

Many older adults coming out of prison have spent decades locked up, making it even harder for them to adjust to life on the outside, said Jennifer Soble, executive director of the Illinois Prison Project, a nonprofit that helps prisoners apply for parole and advocates for laws that increase opportunities for release.

“The longer you remove a person from their families and their communities, the more work they and us as a society will have to do to get them the skills, support, and training they need to thrive independently,” Soble said.

The United States incarcerates a higher share of its population for a decade or longer than any European country, and U.S. prisons are increasingly filled with older adults serving long sentences. In Illinois, people age 50 and older make up about 22% of the prison population, up from 4% in 1988. More than two-thirds of older adults in prison as of December 2022 were serving sentences of more than a decade.

Long prison sentences have had a disproportionate impact on Black Illinois residents, who make up less than 15% of the state population but more than 60% of people with expected prison stays of 15 years to life, according to a recent report by FAMM, a national advocacy group formerly known as Families Against Mandatory Minimums.

A growing body of research shows that long sentences have no real positive impact on public safety. According to a statistical analysis published in January 2023 by the Council on Criminal Justice, a nonpartisan research group, reducing long prison sentences in Illinois by 30% would result in “a virtually undetectable increase” in annual arrests.

These long prison sentences disqualify many older former prisoners from some Social Security and Medicare benefits, which are predicated on wages earned throughout one’s lifetime — and prison wages generally don’t count toward those benefits.

For Covelli, who spent more than half of his life behind bars, this means he didn’t earn enough to qualify for disability insurance, even if his back issues or mental health diagnoses might someday make it impossible for him to work.

Since 1978, when Illinois ended discretionary parole, there have been few avenues for early release for people with long sentences. Under the state’s “truth-in-sentencing” laws, which went into effect in 1998, prisoners must serve between 50% and 100% of their sentence, depending on their conviction.

In recent years, lawmakers introduced some new pathways to release, but few people have benefited. Cook County prosecutors filed motions last year asking judges to resentence three men, ages 55 to 63, under a new state law allowing for resentencing “in the interest of justice,” but none of the men were resentenced.

Under a separate law, prisoners who are terminally ill or medically incapacitated could start applying for parole in January 2022. As of April 2023, only 39 people have been paroled out of more than 340 applicants, data obtained by Injustice Watch shows.

More than half of the applicants were deemed unqualified for parole under the law, which requires a diagnosis from a prison doctor who says they’ll likely be “medically incapacitated” — meaning they can’t bathe or dress themselves — within six months or dead within 18 months.

Democratic state lawmakers have repeatedly introduced an “elder parole” bill, which would expand parole to older adults who have served at least 25 years in prison. But despite passing the Illinois House of Representatives’ criminal justice committee in March 2023, the bill has stalled in the current legislative session.

If such a bill had been in place when Covelli was in prison, he would’ve been eligible for release more than a decade ago.

“I would’ve still been a young man or at least a younger man,” he said. “Who knows where I’d be right now. Probably not where I am.”

Jonah Newman contributed data reporting to this story.