On March 31, 1981, Mayor Jane Byrne and her husband, Jay McMullen, moved from their Gold Coast, high-rise apartment into the Cabrini-Green Homes, a housing project on Chicago’s Near North Side. Some called it “brave,” while others condemned it as a publicity stunt.

During World War II, the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) tore down an old slum neighborhood nicknamed “Little Hell” and built an apartment project for laborers supporting the war effort. The two-story row homes were named for American Saint Frances Xavier Cabrini. The housing authority continued to expand the project over the next decade, adding high-rise buildings. In the 1960s, CHA built even more units called the William Green Homes. By this point, the population of Cabrini-Green was majority-Black, as segregation policies took hold. (The CHA was found liable in a 1969 lawsuit for racially discriminatory practices.)

By the time Jane Byrne was mayor, high crime had plagued the troubled housing complex for more than a decade. Shootings and gang-related violence had spiked in early 1981. In her 1992 book, My Chicago, Byrne recalls driving by the complex.

“As we approached the huge campuslike setting of high rises, low rises, and townhouses nestled together, I noticed a starkness,” she writes. “It was lunch hour, yet the playgrounds and parks were virtually empty. Where were the children? And where were the police. No sign of them, either.”

When Byrne visited another time, she encountered a police scene in which a young girl had been gang raped. “How could I put Cabrini on a bigger map? Suddenly I knew – I could move in there,” she writes.

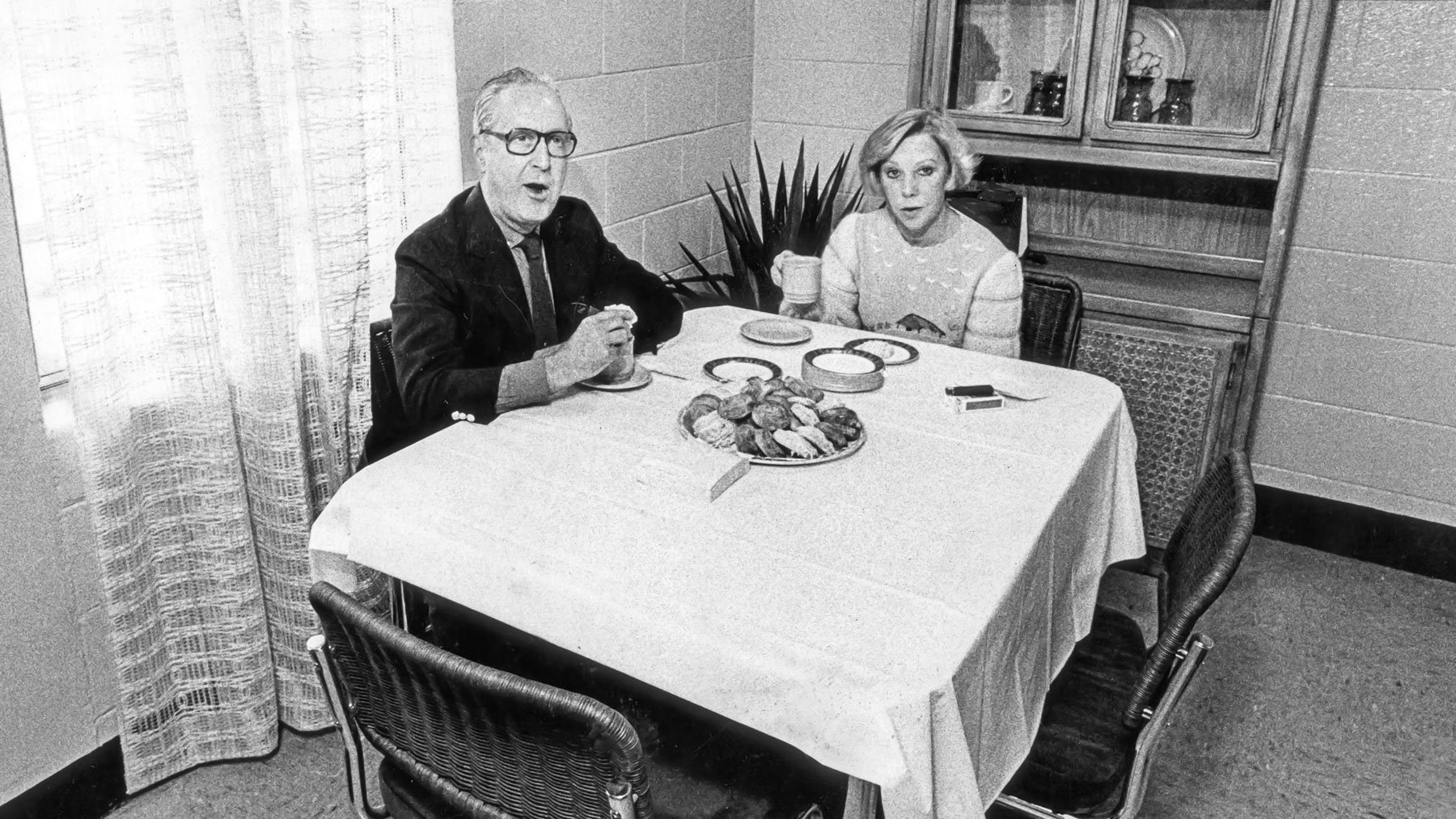

Byrne and her husband – along with two bodyguards – moved into a fourth-floor apartment. Byrne recounts that she met with children who would knock on her door every night.

“Living in Cabrini was not uncomfortable, but all in all it was a sobering experience,” she writes.

The public’s view on the move was mixed.

“I thought it was a daring and really smart decision. Not everybody agreed,” Carol Marin, who covered Byrne as a reporter at the time, told Chicago Stories. “Give her credit for bringing attention to a place that most people would rather look away from, not drive by, don’t go in that neighborhood. And so I thought what she did, while it may not have had a long-lasting effect, I think what she did was bold.”

“I think it was largely viewed as what it was – it was a gimmick,” David Axelrod, who was also a reporter at the time, told Chicago Stories.

While Byrne stayed at Cabrini, the elevators were fixed, trash was picked up, and the violence stopped for a few weeks.

“Hey, there's paint! All of a sudden you’ve discovered paint for Jane Byrne! All of a sudden you discovered rodent control. Where’s all that been all this time?” Jacky Grimshaw, initially a Byrne supporter who would later become a precinct coordinator for Harold Washington, told Chicago Stories. “By moving in, it just pointed to the inequalities of what was going on in Cabrini.”

Byrne and her husband lived at Cabrini-Green for three weeks, and after they moved out, the challenges facing Cabrini-Green persisted. In 1997, Mayor Richard M. Daley announced a redevelopment plan that would demolish most Cabrini-Green housing. In 2011, the last high-rise was razed, and many of its residents were displaced, though some of the two-story row houses still stand.