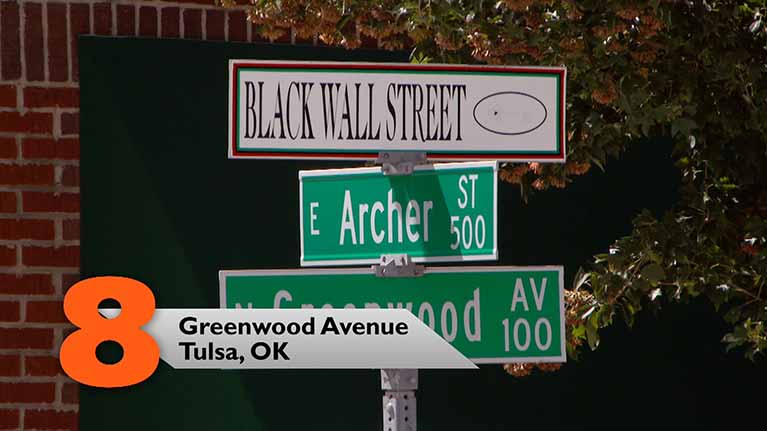

Greenwood Avenue

Greenwood Avenue

Visit what was once known as the “Black Wall Street” until a violent mob burned it to the ground in 1921.

Streets can draw together people from diverse backgrounds and far-flung neighborhoods or lead people through communities that they otherwise might never encounter.

But they also have a long history as geographic dividing lines between “us” and “them,” demarcating neighborhoods by class, background, and race.

In Tulsa, Oklahoma, for more than a century, the black population was excluded from living or owning a business in downtown Tulsa. And although the oil boom of 1901 brought an infusion of money into the local black community, they didn’t gain access to white society – unless they were working as a maid or butler.

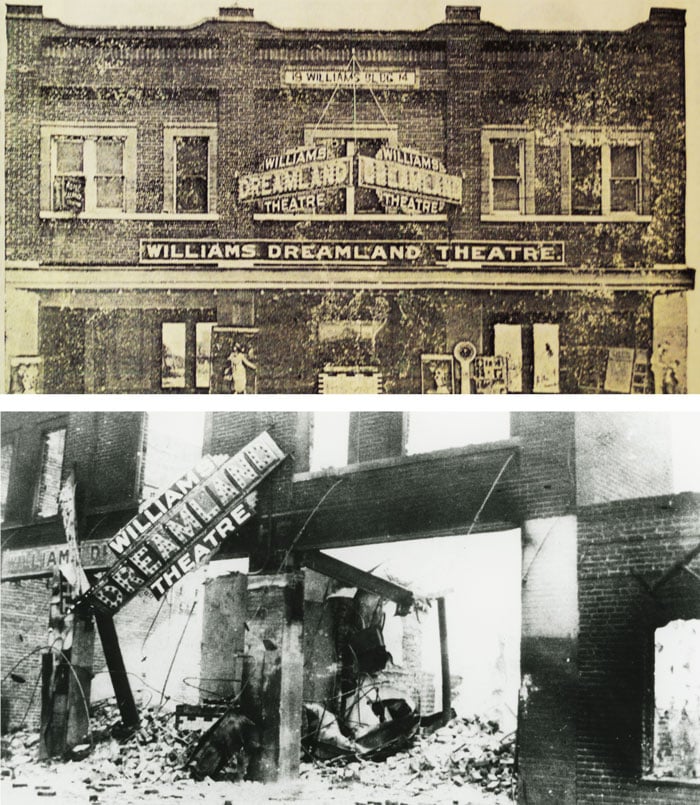

But on the other side of the tracks, along Greenwood Avenue, black businesses and society flourished. It became, in a way, its own separate town with its own nightclubs, attorneys, and jewelers. Greenwood Avenue was home to fifteen doctors, four hotels, two theaters, and two newspapers. Among locals, it was called “Black Wall Street.”

“There’s such potential here,” said John W. Franklin, the noted historian and grandson of one of Greenwood’s most prominent attorneys in those days, Buck Colbert Franklin. “There’s such excitement here and such a future, everyone believes,” he said. “And then, of course, it all comes to a screeching halt…June 1, 1921.”

Many of Tulsa’s white residents, particularly those who didn’t own land, were seething with resentment over black success. Lynchings became a common tool used to instill fear and maintain the racial hierarchy. And as soon as Oklahoma became a state in 1907, the legislature codified racial segregation and discrimination. In case that wasn’t enough, in 1914, the City of Tulsa passed its own segregation ordinance, forbidding blacks or whites from residing on any block where three-fourths or more of the residents were of another race.

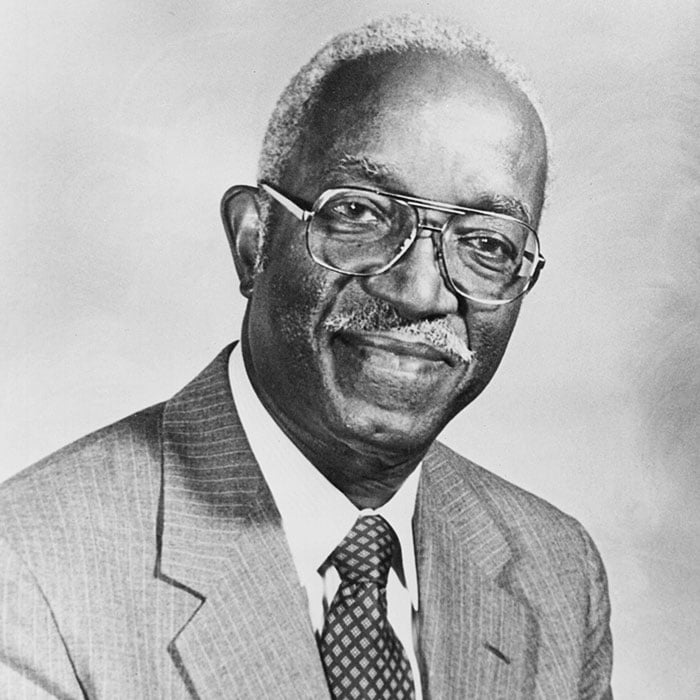

Buck Colbert Franklin moved to Greenwood in early 1921 to establish a law office there. He saw an opportunity to create a better life for his family and to help black and Native American landowners negotiate fair oil leases. They had been sold or given their land because it had previously been deemed worthless. Now that the dry soil was discovered to have oil running underneath it, he wanted to make sure they got a fair shake.

Franklin’s wife, a schoolteacher, planned to follow months later with their children, after the school year ended.

Then on May 30, 1921, a young black man named Dick Rowland stepped into a downtown elevator operated by a 17-year-old white girl. Rowland often used the elevator in the Drexel Building, where he shined shoes, to use the bathroom upstairs, per an agreement with his employer. No one knows what happened in that elevator, but the afternoon edition of that day’s Tulsa Tribune claimed that he “attacked her, scratching her hands and face and tearing her clothes.”

“Her screams brought a clerk from Renberg's store to her assistance and the Negro fled,” the report reads.

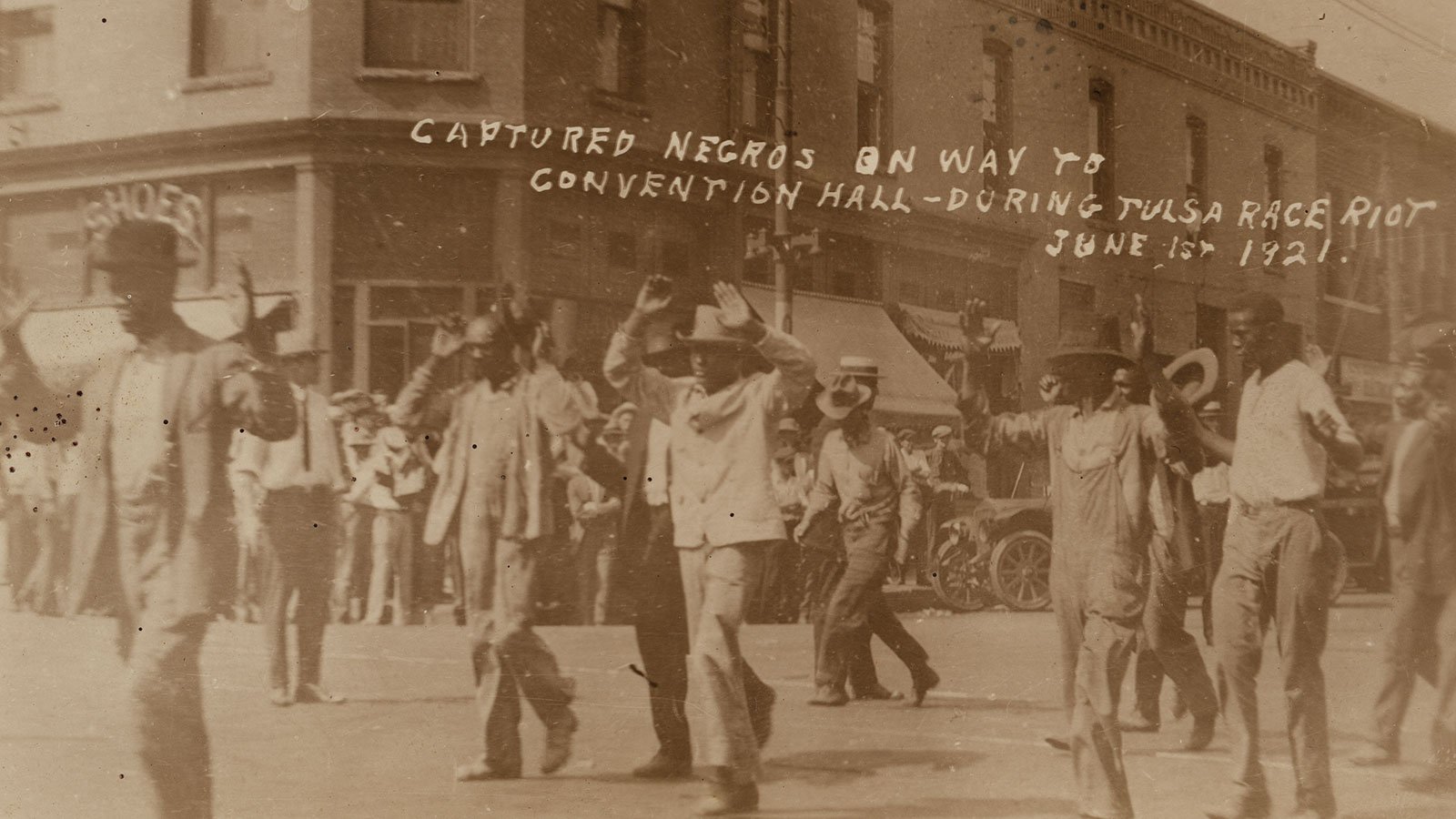

Rowland was later arrested on Greenwood Avenue and brought to a jail cell downtown, above the courthouse. Afraid Rowland might be lynched, a cadre of armed, black, World War I veterans arrived to guard the courthouse overnight. Soon, a crowd of angry white residents also arrived, and there was a confrontation. A gunshot was fired, no one knows by whom, but by early morning, thousands of angry white residents had amassed. They crossed the tracks onto Greenwood Avenue, brandishing rifles and other weapons, including a machine gun.

The machine gun was set up on a hill overlooking the black district, and the angry mob opened fire.

“We have the eyewitness accounts of people hearing what they thought was hail hitting their homes and it’s actually bullets, and they can see the machine gun with an American flag on it,” said Franklin. “People were machine gunned down in the streets.”

Referring to his grandfather’s written account, Franklin said, “There is a scene where he witnesses people being shot in front of him in cold blood in the street and also miracles of a woman and her child spared the bullets, even though they’re in the midst of this madness, confusion,” said Franklin.

Airplanes bombarded Greenwood from above, dropping what Franklin’s grandfather described as “explosives.”

“I’m thankful that my father and his younger sister and mother are not here because they may have perished,” said Franklin.

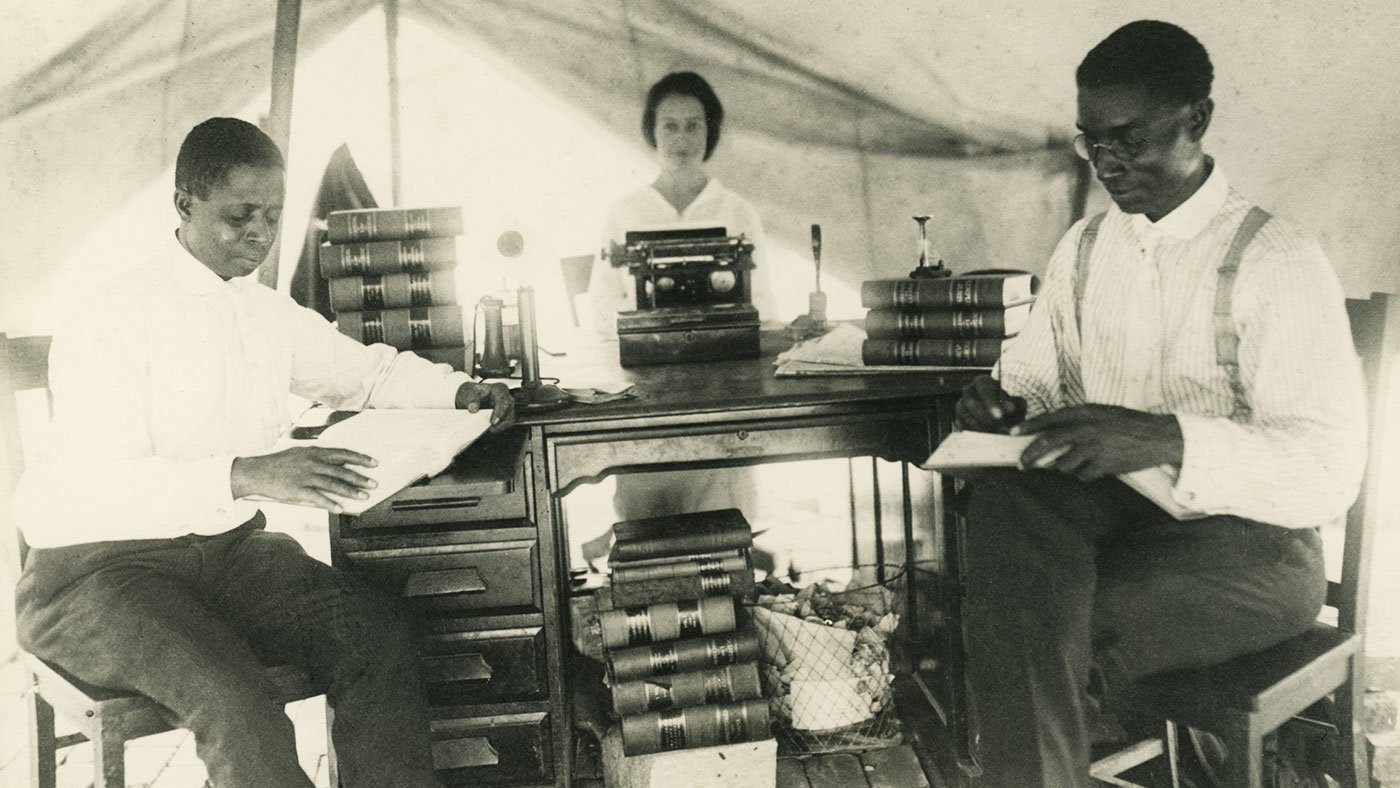

Thousands, including Franklin’s grandfather, were arrested and detained for several days in makeshift mass-detention facilities, including a local theater and a ballpark.

Forty square blocks in and around Greenwood Avenue had burned to the ground, leaving approximately 9,000 people homeless. No one knows for sure how many died; figures range from 38 to 300 killed.

Buck Franklin lost everything but his life. “The money he saved to welcome his wife and children is burned up with all his possessions,” said Franklin. “His office is burned. He has nothing.”

There was little help for the victims. Insurance companies refused to compensate them, claiming that riots fall under the “act of God” exception. But the Red Cross came to Tulsa and provided some assistance.

Buck Franklin stayed in Tulsa and continued to work for his community, practicing law out of a Red Cross-issued tent.

Many other black residents also stayed and rebuilt Greenwood. Four years later, the National Negro Business League held their annual convention there.

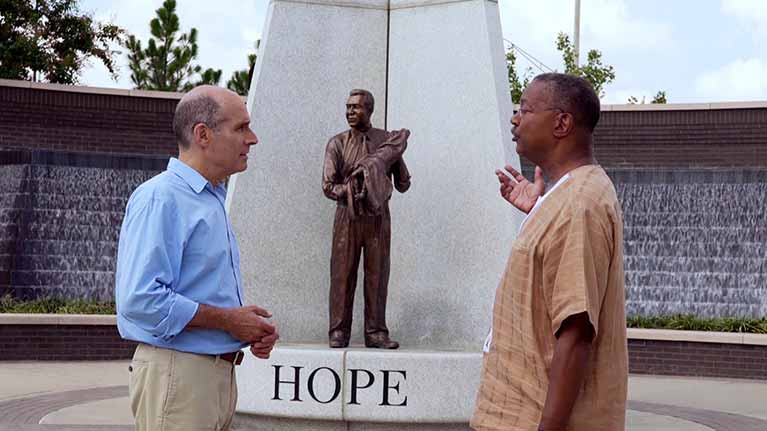

“The city continues and thrives, and that’s why it’s a story of resilience,” said John W. Franklin, walking down modern-day Greenwood Avenue. “You notice the dates on these buildings: 1922, 1923…The houses are around here, and the neighborhood and the businesses continue.”

But where the tracks had once served as the unofficial dividing line between Greenwood Avenue and white Tulsa, soon an even bigger barrier would rise: the interstate. Franklin says was a deliberate decision that effectively unraveled the local black community.

“This is the fifties; [we] don’t have voting rights yet. So when the decisions are made where to build a highway, we have no voice,” said John W. Franklin. “The highway comes straight through this business district, and it never really recovers.”

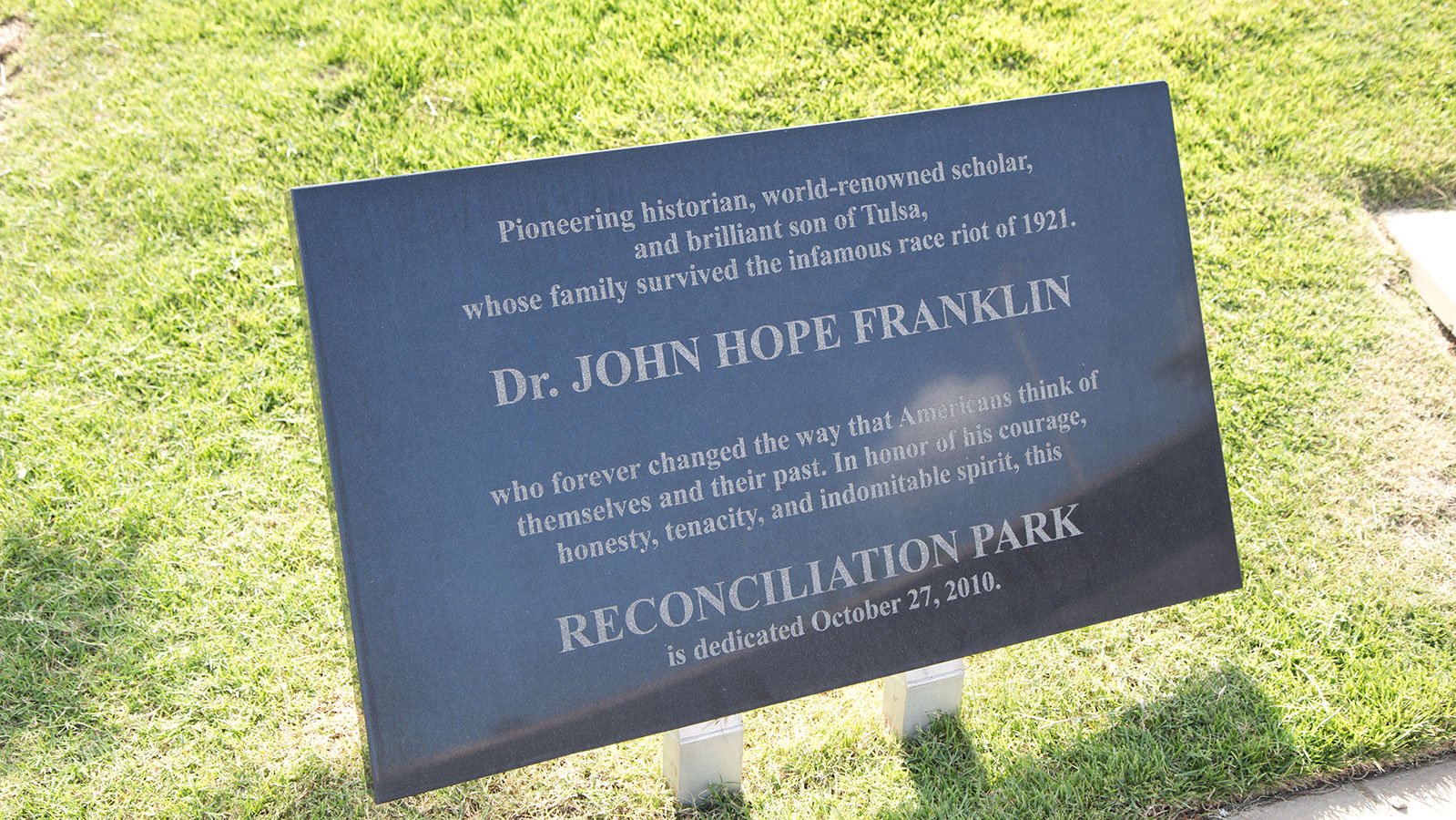

Reconciliation Park is just one part of a larger effort to remember and learn from what transpired along Greenwood Avenue in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

And it wasn’t just in Tulsa. “Throughout America, the interstate system destroys black business districts, because they’re the weakest in political power to resist,” said Franklin, now a cultural historian at Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Residents of Tulsa, meanwhile, still struggle to come to terms with their past. For many years, said Franklin, white Tulsans “told their children not to talk about it.”

“Tulsa is still a very divided city, and this is a hidden and shameful history, and so it’s very difficult for people to talk about,” said Franklin.

It wasn’t until 2010 that a state commission studied the causes of the Tulsa massacre. Out of that discussion, a group of residents decided to create the park as a way of remembering and documenting their history for current and future generations.

Today, near this street that’s long been separated from the rest of the city, there is a new “Reconciliation Park,” named for a famous scholar of African American history: John Hope Franklin, John W. Franklin’s father, with whom he co-authored his grandfather's biography.

The park memorializes what is often referred to as the “Tulsa Race Riot” and tells the story of African Americans’ role in building Tulsa and Oklahoma.

“The idea of the park is to bring people together,” said John W. Franklin.