Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg, Virginia

In 1698, the Jamestown settlement that had served as the capital of England's Virginia Colony burned down. For political reasons as well as practical ones, colonial officials transferred the capital to the small town of Middle Plantation.

The new site had all of the required advantages: a high location, a brick church, freshwater springs, even a new college named after King William and Queen Mary. At first, the move was supposed to be temporary, but in 1699, the House of Burgesses decided to make it permanent.

When Governor Francis Nicholson moved to the newly rechristened Williamsburg, he was determined to have a formally designed capital city, despite obstacles both man-made and natural.

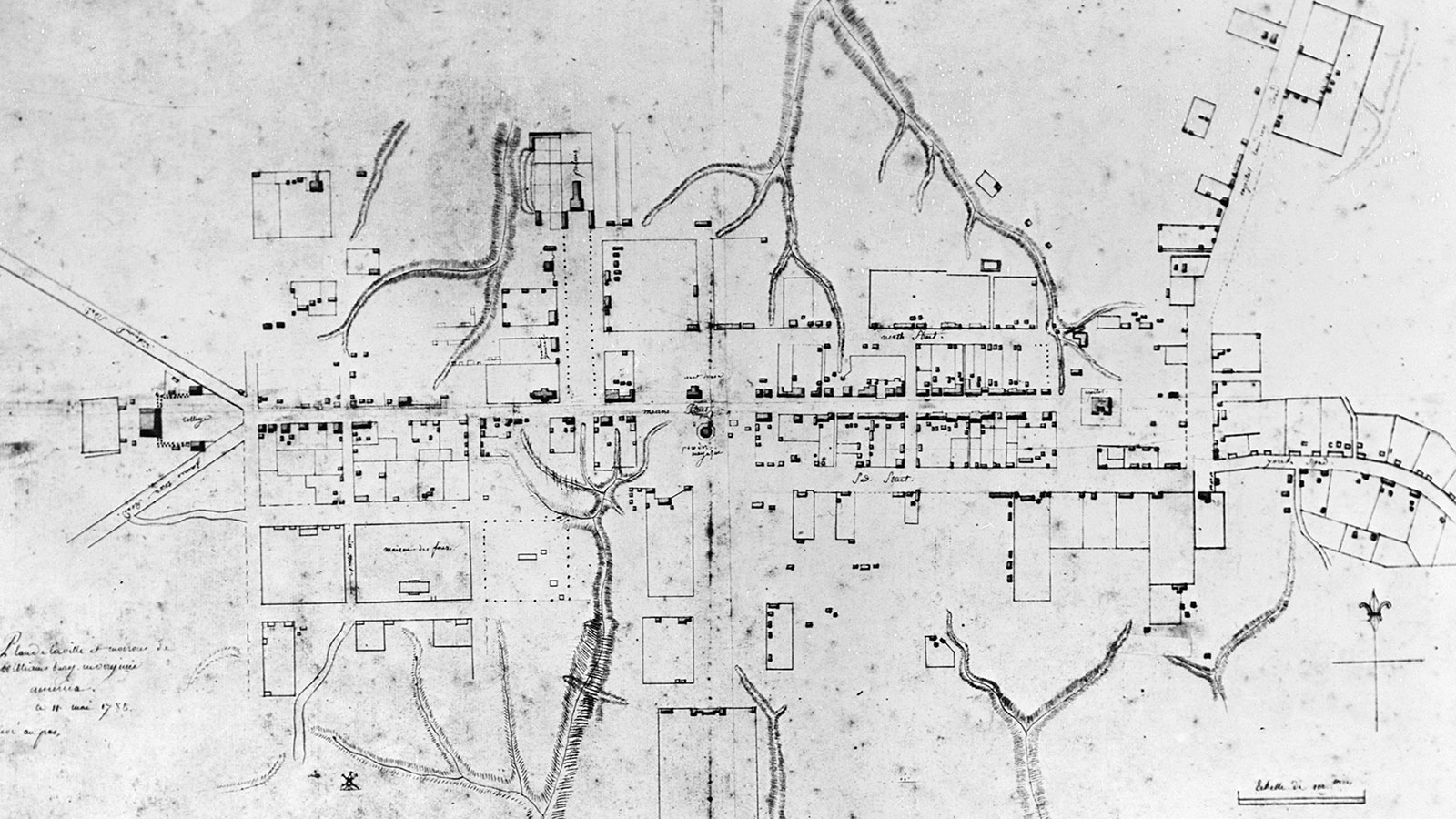

Nicholson imposed a formal plan over the existing village. The centerpiece was a 99-foot-wide main street between the college and the new Capitol building. Almost a mile long, this thoroughfare, named Duke of Gloucester Street, anticipated the growth of the settlement.

Houses were required to be within six feet of the street. A market square divided the street in half. A second formal axis to the north opened up a striking view of the new Governor's Palace.

Houses that already stood in the path of the new street had to be torn down. Using the power of eminent domain, Nicholson's government dismantled the houses and returned the bricks to their owners.

The natural ravines that crisscrossed the town site were harder to manage. Duke of Gloucester Street and the parallel streets to either side - named "Francis" and "Nicholson" by none other than Governor Francis Nicholson himself - had to traverse the ravine, down one side and up the other, until the ravines were filled in.

Despite these challenges, Nicholson's plan provided a framework from which town residents could build their houses and businesses. Williamsburg soon became one of the largest and most important cities in the colonies. Its fortunes did not change until after the Revolution, when the capital was moved to Richmond.

In the 1920s, long before there was an organized preservation movement in America, the local parish rector convinced millionaire John D. Rockefeller that the extraordinary collection of eighteenth century architecture in Williamsburg was worth preserving. An organization called Colonial Williamsburg was formed to restore buildings and construct new ones to replicate the buildings that had been lost.

Work began in 1927. In the first two decades, more than 80 buildings were restored, and more than 300 new ones constructed.

Restored and rebuilt, Colonial Williamsburg now attracts hundreds of thousands of visitors a year who come to the town to learn about and experience America's colonial history.