18th STREET and PRAIRIE AVENUE

South Loop

The Battle of Fort Dearborn left more than 50 soldiers and settlers dead, including women and children. Those not killed were taken prisoner; some were later ransomed.

The area around 18th Street and Prairie Avenue on Chicago’s near South Side was the setting for some of the most dramatic scenes in the city’s early history. These stories illustrate how quickly and dramatically fortunes could shift for the city’s 19th-century inhabitants.

Battle of Fort Dearborn

Watch the Segment

Fort Dearborn sat on the south bank of the Chicago River at what is current-day Michigan Avenue. In 1812, it was the westernmost outpost of the nascent United States. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

Some geographic context for the battle of Fort Dearborn: in 1812, the main branch of the Chicago River did not flow straight into Lake Michigan. Just east of Fort Dearborn, it curved south through dunes to the west and sand bars to the east (both of which sat much further inland than today’s landfill extends) and did not empty into the lake until closer to current-day Madison Street. Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

Learn More:

Visit the Prairie District Neighborhood Alpance website.

During the War of 1812, U.S. Army commander William Hull ordered the evacuation of Fort Dearborn, located near the mouth of the Chicago River. Nearly 90 soldiers and settlers made their way toward what they hoped would be safety at Fort Wayne, in Indiana territory.

But just two miles south of Fort Dearborn, as they traveled along the beach near what is now 18th Street and Prairie Avenue (remember that the Chicago shoreline was further inland then than it is today), the group saw a band of Potawatomi Indians hiding in the dunes.

Fearing they were about to be attacked, the soldiers fired at the Potawatomi. What happened next has, at different times in history, variously been called a massacre or a battle. What is clear is that it did not go well for the soldiers, who were outnumbered five to one by the Potawatomi.

The battle lasted only 15 minutes and, at the end, more than half of the soldiers and settlers were dead; those remaining were captured. The Potawatomi set fire to Fort Dearborn and later ransomed most of their captives.

While the Potawatomi won this battle, they would later find themselves outnumbered and outgunned. Just 25 years later, they would be pushed off their ancestral lands and out of the area for good.

Prairie Avenue District

After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, the area around Prairie Avenue and 18th Street became the breeding ground for a new era of warriors: those battling for dominance in the business world.

Chicago’s leading tycoons, magnates, and robber barons built a “millionaires’ row” of grand mansions here, including department store tycoon Marshall Field, railroad industrialist George Pullman, farm machinery manufacturer John J. Glessner, and meatpacking magnate Philip Armour.

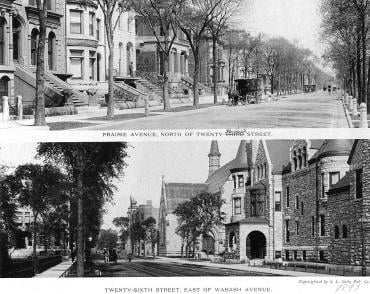

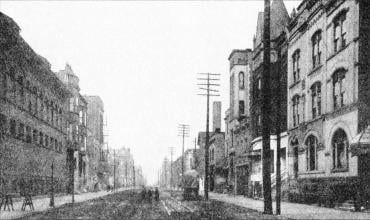

After the Great Fire of 1871, Chicago’s industrialists built mansions along Prairie Avenue. “Millionaires’ Row” included homes designed by H. H. Richardson, Daniel Burnham, and other notable architects. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

Levee District

But the grandeur of Prairie Avenue would not last. Its star dimmed, in part, due to a notorious vice district just to the west. The Levee District rose during the 1893 World’s Fair, scandalizing the genteel inhabitants to its east with lurid nightlife.

It was not the only vice district in town, but it was the most unapologetically sordid one, possibly because it enjoyed protection by such powerful local officials as Democratic Committeeman Mike “Hinky Dink” Kenna, who helped keep its brothels, saloons, and gambling parlors operating without interruption from the police. By the time the Levee was shut down in 1912, it had done irreparable harm to Prairie Avenue’s reputation.

Over time, Prairie Avenue became less fashionable as the millionaires moved north. Mansions deteriorated and were divided into rooming houses. Most were eventually demolished. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

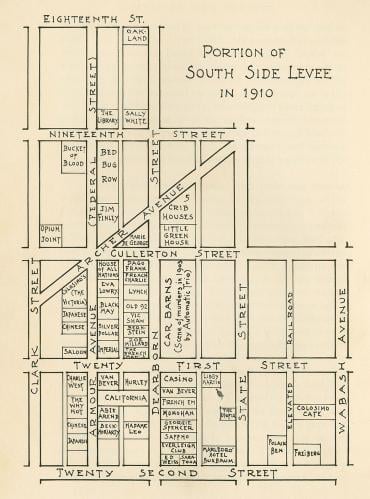

One of the reasons for Prairie Avenue’s decline was a nearby vice district that flourished during the World’s Colombian Exposition of 1893 and thereafter. Brothels, gambling parlors, and saloons with colorful and lurid names brought a new and different character to the area. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

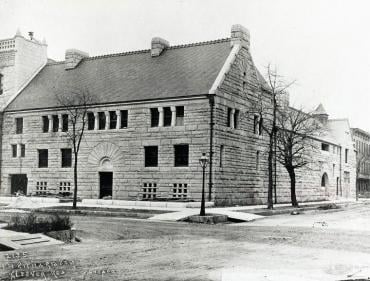

One mansion still standing on Prairie Avenue is the 1887 house designed by architect Henry Hobson Richardson for John J. Glessner. The home’s design, a dramatic departure from the Victorian style of other Prairie Avenue mansions, inspired a young Frank Lloyd Wright. Glessner House is open to the public and offers tours and information about the surrounding area. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

Motor Row (Michigan Avenue south of Roosevelt Road)

Also nearby, commercial development continued to increase all around Prairie Avenue. After 1900, a growing collection of auto showrooms and repair shops rose along (and around) South Michigan Avenue, feeding the rapidly growing appetite for the horseless carriage. The increase in auto registrations in Chicago tells the story: from 300 in 1900, to 90,000 in 1920, to an astounding 300,000 in 1925.

On Motor Row, Chicagoans could browse the showrooms and purchase Fords, Buicks, Studebakers, Hudsons, Cadillacs, Pierce-Arrows and dozens more makes. They could also attend auto shows at the nearby Coliseum to see the newest models.

“Motor Row” rose along South Michigan Avenue after 1900, providing showrooms with every make and model to feed the exploding demand for automobiles. Photo Credit: Wiki Commons Andrew Jameson

The home of department store innovator Marshall Field. Other Prairie Avenue residents included railroad industrialist George Pullman, farm equipment manufacturer John J. Glessner, and meatpacking magnate Philip Armour. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

The home of railroad industrialist George Pullman and his wife Harriet was one of Prairie Avenue’s most lavish, with an interior described by a local newspaper as “more beautiful than the Gardens of Cashmere.” It was not uncommon for the Pullmans to entertain 400 or more people at a time. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

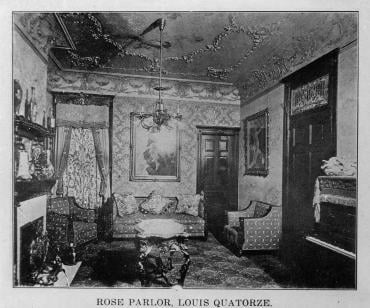

The Everleigh Club was a high-class brothel that operated in the Levee District, catering to some of the city’s most notable names. It had in common with its Prairie Avenue neighbors a lavish interior. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

The Everleigh Club was operated by sisters Minna and Ada Everleigh. They paid protection money to aldermen and police so they could continue to operate freely. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum

The Everleigh Club operated in two brownstones on the 2100 block of South Dearborn Street. Today, the street grid has been altered, and the site holds a Chicago Housing Authority property designed by Bertrand Goldberg called the Hilliard Towers Apartments (formerly Hilliard Homes). Photo Credit: Wiki Commons

First Ward Alderman John Coughlin, known as “Bathhouse John” (right), and Democratic Committeeman Michael “Hinky Dink” Kenna were critical players in the mix of corruption, graft, and bribery that made the Levee’s vice-ridden operation possible. Photo Credit: Chicago History Museum