PALOS FOREST PRESERVE

Southwest Suburbs

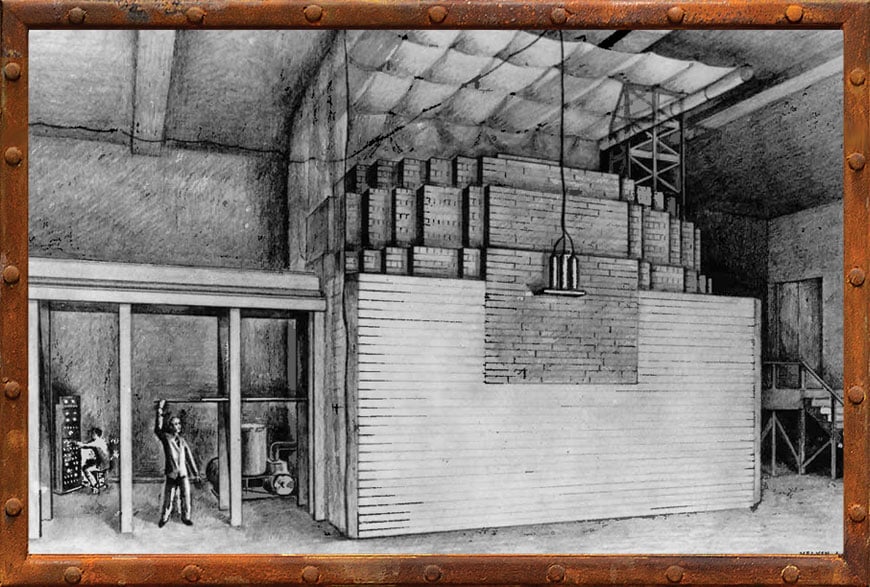

On December 2, 1942, a group of 49 scientists led by Enrico Fermi created the world’s first controlled nuclear chain reaction beneath the stands of the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field. It would change the course of history. Photo Credit: Argonne National Laboratory

Watch the Segment

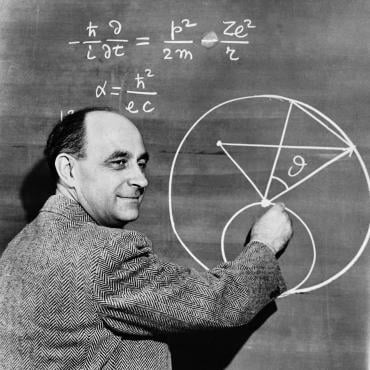

Enrico Fermi was already a Nobel Prize-winning physicist when he came to Chicago. He traveled to Sweden to accept the award in 1938; he and his family emigrated to the U.S. rather than return to fascist Italy. Photo Credit: Argonne National Laboratory

During World War II, Chicago played a crucial role in the development of the first atomic bomb. Physicist Enrico Fermi and his team were working intently to create the world’s first controlled chain reaction in the hope that they might deliver a weapon that could end the war.

Not only was their work top secret, it was also extremely dangerous. In 1943, they moved their nuclear reactor – and the huge pile of enriched uranium needed for the chain reaction and the experiments that followed their first successes – from a former squash court under Stagg Field at the University of Chicago to a more remote area in Palos Hills.

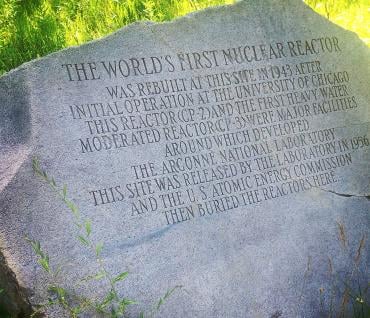

They succeeded in their goal. But what to do with all that radioactive material? A good deal of it was ultimately buried in what is today the Palos Forest Preserve. Markers discourage picknickers from digging.

Nuclear research moved from the University of Chicago to a site in Palos Hills after the first successful chain reaction. After the war, the lab was renamed Argonne National Laboratory and continued nuclear research on the site for nearly ten years. Photo Credit: Argonne National Laboratory

The site closed in 1956. The reactor and some of the nuclear material from the experiments were buried here and remain underground to this day, capped by a concrete barrier. Photo Credit: Argonne National Laboratory

Markers discourage visitors from digging and assure them of their safety. However, trace amounts of radioactivity were discovered in wells serving the picnic areas in the 1970s. The Illinois Department of Public Health claims that the material “… poses no apparent public health hazard because human exposure to contaminants is infrequent, of short duration, and likely negligible.” Photo Credit: Argonne National Laboratory