By the mid-20th century, Chicago was known as the candy capital of the country. What began as modest operations in the mom-and-pop kitchens of European immigrants eventually grew into a large industry. By 1940, Chicago candymakers produced some 556 million pounds of candy per year. Chicago had all the ingredients for confectionery success. It had a skilled, diverse workforce. It was in the sweet spot, too – conveniently located in the heart of the country. It even had (though this may surprise Chicagoans who have endured many a cold winter) the right climate, with cooler temperatures more ideal for making and shipping things that had a habit of melting before refrigeration was common.

“Chicago becomes this mecca for people that have some candy-making skills, some chocolate-making skills. You know how to make dragées from Italy, nougat from France. You’re skilled in hard candy from England,” Beth Kimmerle, author of Candy: The Sweet History, told Chicago Stories. “What happens is that’s reflected in the candy. I mean, literally, the copper pot becomes the melting pot of candy.”

From the crunchy and the sticky treats to the chewy and the chocolatey ones, the iconic confections that came from Chicago’s candy companies became household names.

1. Ferrara Candy

At the turn of the 20th century, Salvatore Ferrara came to the United States as a teenager with “literally nothing,” his great-grandson, Nello Ferrara, told Chicago Stories.

“He had a set of skills in his back pocket, which was working in a bakery making small confections,” Nello Ferrara said.

After teaching himself English and working for the Sante Fe Railroad as an interpreter, Salvatore saved up money and opened a bakery in Chicago’s Little Italy neighborhood with his brother and brother-in-law. The bakery’s sugar-coated almonds, called “confetti,” were especially popular.

In 1932, according to Susan Benjamin’s book, Sweet as Sin, the company introduced Red Hots as its first branded item. (Prior to Red Hots, the company sold its products mostly as wholesale items.) With that spicy, cinnamon-flavored hard candy, the Ferrara brand was born. Salvatore’s son, Nello V. Ferrara, later grew the company and focused its operations on panned candies, changing the company name to Ferrara Pan Candy Company.

To make panned candies, “companies produced the sweets in a ‘pan’ that looks like a small cement mixer,” writes Benjamin. The company found success with its pan candy, including well-known treats such as Jaw Busters, Atomic Fireballs, Boston Baked Beans, and Lemonheads.

In the early 2000s, many Chicago confectioners that were once family owned merged with other companies or relocated to keep up with the rising cost of production. Ferrara Candy merged with Minnesota-based candy company Farley’s and Sathers in 2012, ending its time as a family-run business, and was later purchased by Italian-based parent company Ferrero Group. Today, the company continues to produce Trolli Gummy Worms and several other household candies, such as Laffy Taffy, Nerds, and Jujyfruits.

2. Wrigley Gum

When William Wrigley Jr. set out to earn his living as a salesman, he didn’t initially have candy in mind. Wrigley reportedly came to Chicago in 1891 with $32 in his pocket. Wrigley’s father was a soap manufacturer, so he sold soap door-to-door. To boost soap sales, he began offering a free can of baking powder as a premium with each bar of soap.

“The baking powder became more popular than the soap. So he dropped the soap [and] sold baking powder,” Leslie Goddard, author of Chicago’s Sweet Candy History, told Chicago Stories. “Eventually [Wrigley] started offering other premiums, including gum, with every order.”

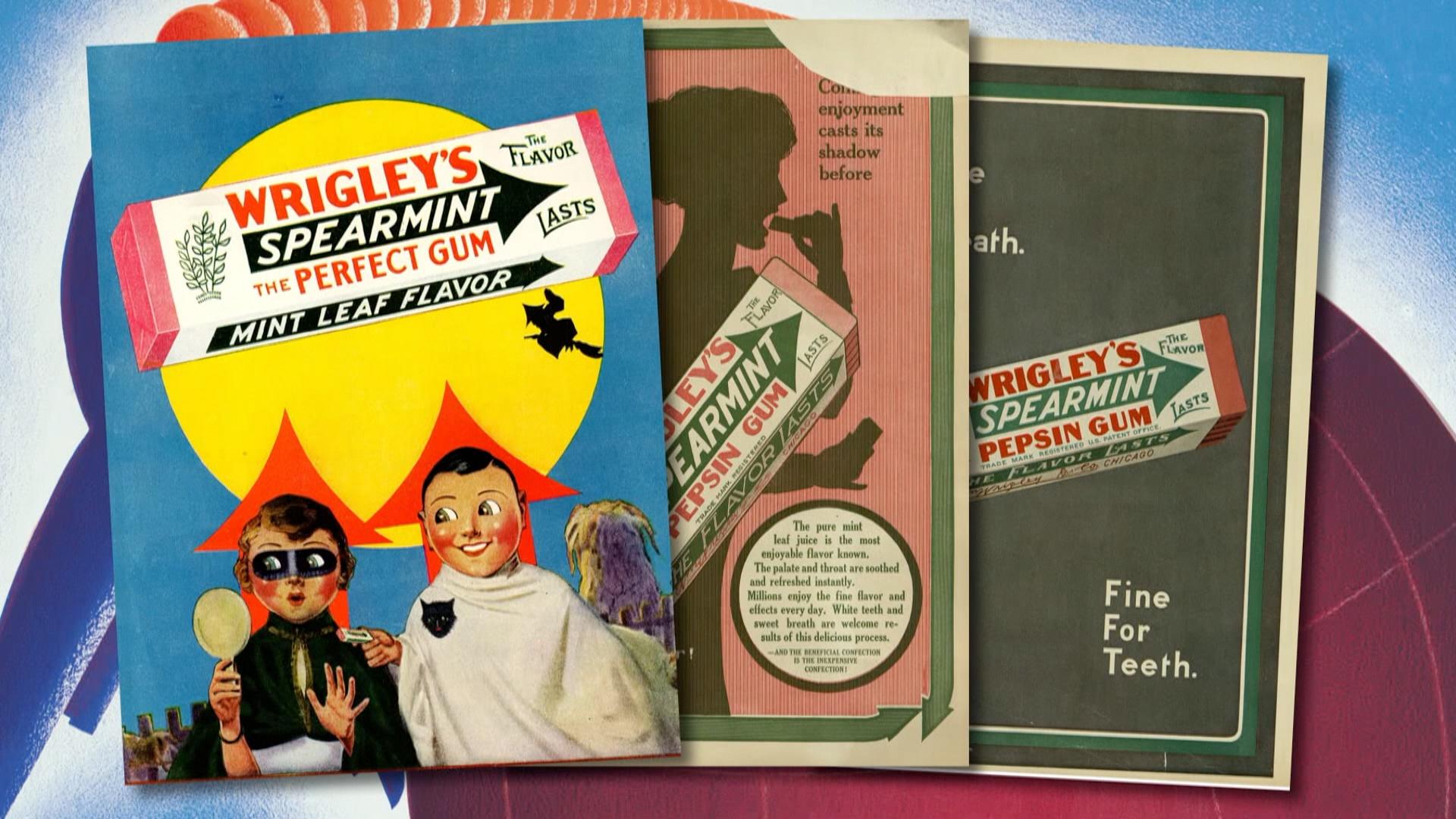

The same thing happened: The gum was more popular than the baking powder. Wrigley bought his gum supplier and began to develop his own flavors: Juicy Fruit, Spearmint, and Double Mint. Goddard said Wrigley was particularly adept at marketing. The marketing motto, “Tell ’em quick, and tell ’em often” is attributed to Wrigley.

“It's very telling that he made such a fortune on three flavors of gum at 5 cents a pack, because what he was doing was extremely innovative marketing,” Goddard said. “When you look at the Wrigley’s ads and especially when you’re looking at the ads from the 1930s…he was using bold graphics, bright colors, minimal text.”

While that style of advertising might be very common today, ads were typically much more text-heavy in the 1920s and 1930s. He also once mailed free samples of gum to anyone listed in the phone book. “If you can afford a telephone, you can afford gum,” Goddard said of his reasoning.

By 1935, Wrigley made 60% of all the chewing gum in America, according to Sweet as Sin. Wrigley’s company was a success – so much so that his very name became associated with the Chicago skyline with the construction of the Wrigley Building. He bought Catalina Island off the coast of Southern California and turned it into a tourist destination for many years. He also became the primary shareholder of the Chicago Cubs in 1921, giving the field the name it still bears. (Alas, his Cubs never won a World Series in his lifetime.) Though the Wrigley family controlled its gum company for decades, Mars acquired the company in 2008.

3. Brach’s

In 1904, a German immigrant named Emil Brach took $1,000 in savings to open his own candy shop on North Avenue in Chicago. He named it Brach’s Palace of Sweets. His operation started out modestly, working with his sons to create candy in a single kettle. He began with caramels and other individually wrapped sweets, such as butterscotch discs and mints. As his business grew, he bought more equipment.

By 1911, according to Goddard in Chicago’s Sweet Candy History, Brach’s company was churning out 50,000 pounds of candy per week. It was Brach’s interest in technology that was a boon for his production.

“E. J. Brach loved technology and equipment. He was constantly experimenting with different methods for mass production,” Goddard said.

Joël Glenn Brenner, author of The Emperors of Chocolate, told Chicago Stories that Brach eventually developed his own wrapping machine.

“By doing that, he took the industry in a whole new direction. He was able to then individually wrap pieces of candy for sale, and he very quickly became a wholesaler,” Brenner said.

By 1923, Brach’s had four factories, and the company was outgrowing all of them. So they built a sprawling new factory on Kinzie Avenue on the West Side. With its new capacity, Brach’s was producing more than 2 million pounds of 127 different kinds of candy a week, writes Goddard. In 1948, an explosion at the factory, which started when a spark set cornstarch ablaze, killed 11 employees and injured 18. But the company rebounded and by the end of the 1950s, Brach’s produced 4 million pounds of candy per week.

Ownership of the company has changed multiple times since the 1960s, but today, Brach’s Candy is made under the Ferrara Candy brand, and the candy is now manufactured in Mexico.

When Batman film The Dark Knight was filmed in Chicago in 2007, a former Brach’s administrative building served as the exterior of one of Gotham’s hospitals. In the famous scene, the Joker blows up the building. It was a practical effect, meaning the real Brach’s building was destroyed.

“The fact that this company that did so much for candy and did so much for so many Chicagoans who worked there was having its end in such a spectacular way really hits you,” Goddard said. “It’s a fabulous moment [in the film], and it’s also a really, really sad moment for anyone who absolutely adored Brach’s.”

Brach’s Candy Corn is still a popular Halloween treat with the company producing, by one estimate, 7 billion pieces of candy corn every year.

4. Curtiss Candy Company

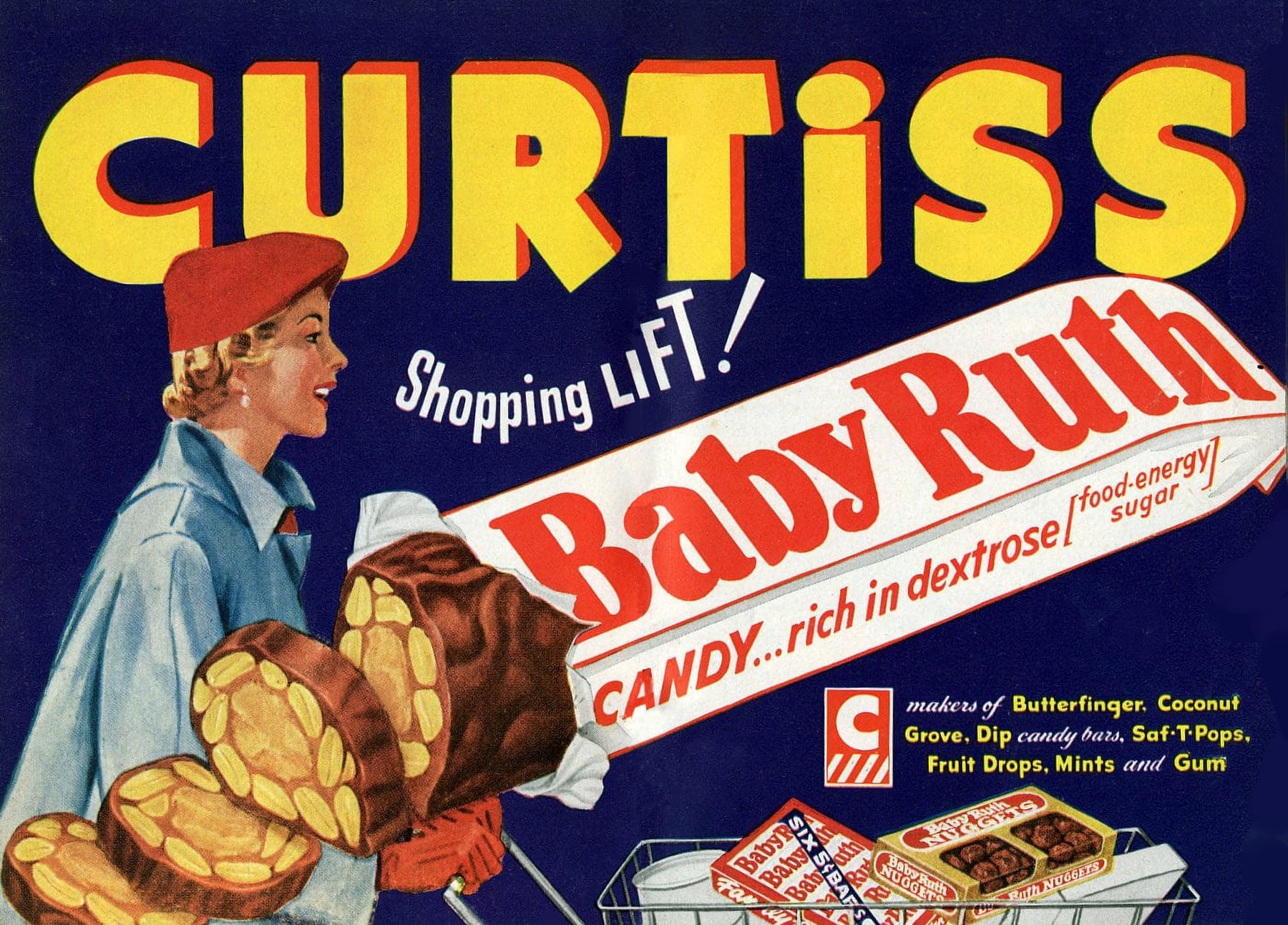

In 1916, Otto Schnering created the Curtiss Candy Company at the back of a plumbing shop on Halsted Street. Amid anti-German sentiment during World War I, Schnering opted to use his mother’s maiden name to name his company.

Just four years after launching his company, Schnering reworked an existing candy bar, called Kandy Kake, into a new bar with peanuts, caramel, and nougat called Baby Ruth. Goddard told Chicago Stories that there are a couple of conflicting origin stories about the name.

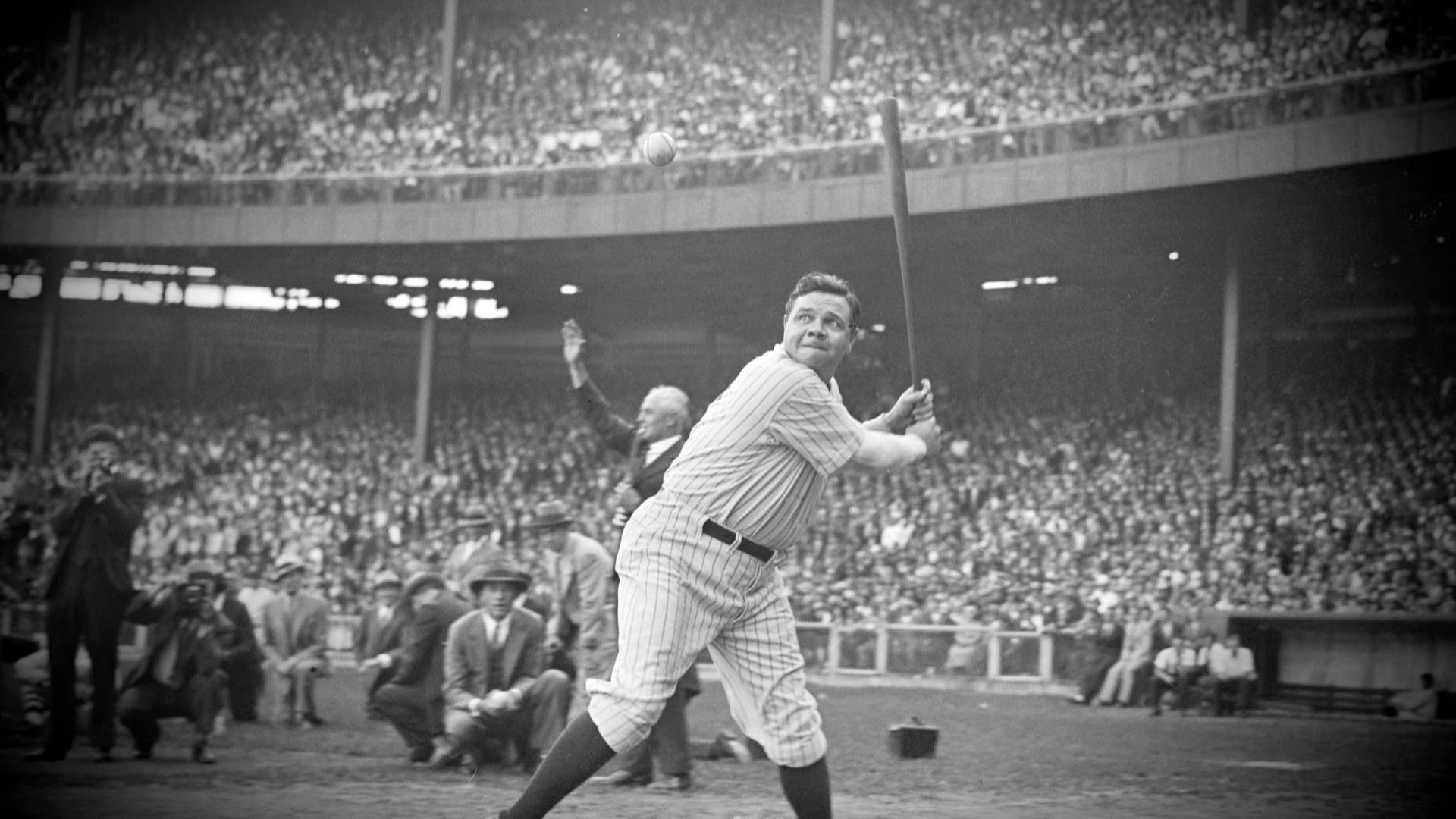

“The Curtiss Candy Company always said it was named for Ruth Cleveland, beloved daughter of Grover Cleveland,” Goddard said. “Historians are a little bit skeptical. Ruth Cleveland, very sadly, died in 1904, and that’s about 16 years before the Baby Ruth bar appears. It seems a little ironic that Babe Ruth, the baseball player, was hitting his peak fame around 1920.”

The company may have come up with the story to avoid any litigation or royalties while being able to leverage the popularity of George Herman “Babe” Ruth, Goddard added.

Schnering also boosted Baby Ruth’s success with quite the marketing stunt: He made it rain candy bars. Schnering chartered a plane to drop a bunch of Baby Ruth candy bars attached to parachutes over Pittsburgh, and later over forty states, according to Brenner in The Emperors of Chocolate. Baby Ruth became a top candy bar by 1925.

He also created a second popular candy bar, a crunchy, flaky chocolate and peanut butter bar which he called Butterfinger. The name of that candy bar also had a sports connection, as it was reportedly named for athletes who couldn’t hold onto the ball.

Though the company was sold in 1964 and later bought by Nabisco, Schnering’s two most popular candy bars are still made today.

5. Mars

Frank Mars was decidedly not successful at his first several attempts at creating a candy company. The financial stress ended his marriage and distanced him from his son, Forrest, who was sent to live with his grandparents in Canada, according to Brenner in The Emperors of Chocolate. Mars finally found modest success when he established another company in Minneapolis called Mar-O-Bar Co. (later renamed Mars, Incorporated).

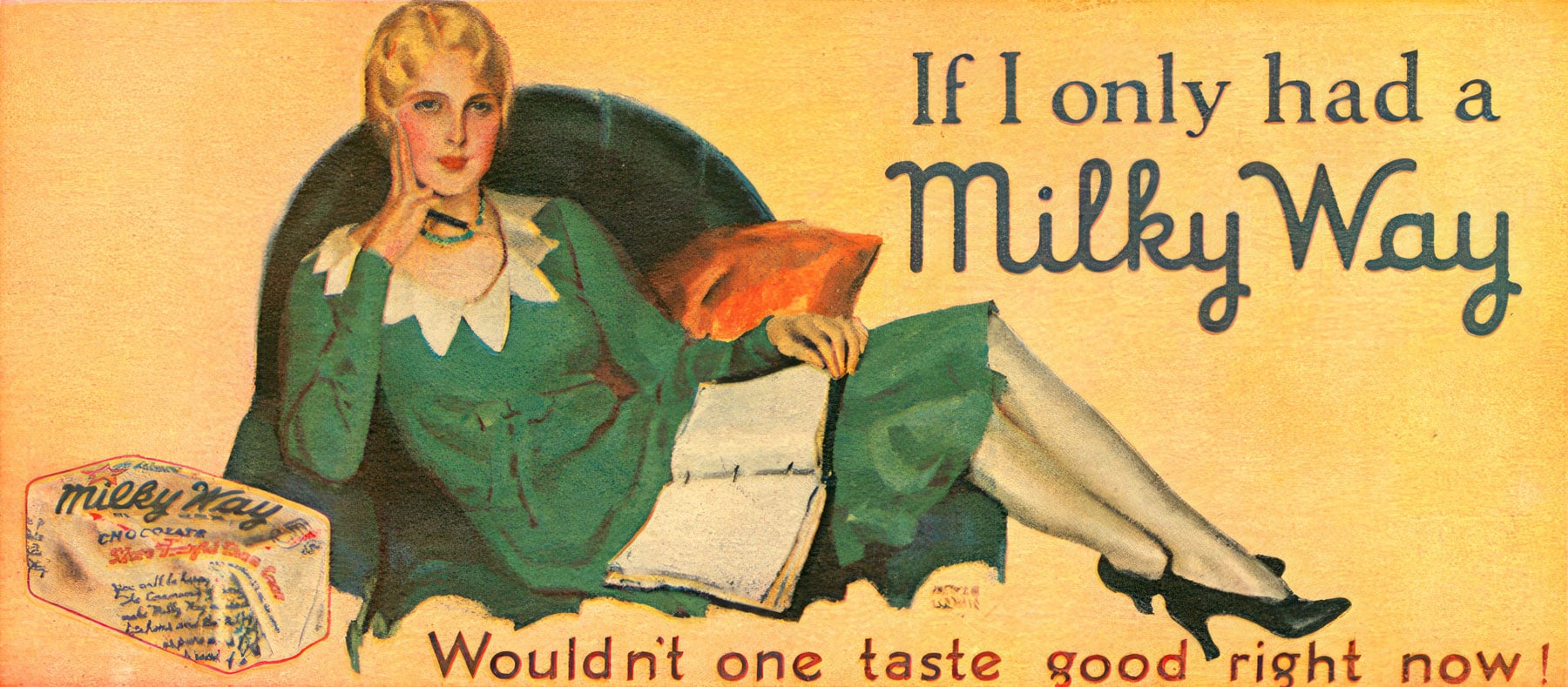

The father and son didn’t reunite until Forrest was an adult, and his dad bailed him out of jail after a bit of legal trouble. When the two men discussed business, Forrest supposedly gave his father the idea for a new candy bar while drinking a chocolate malted milkshake. With that idea, the Milky Way candy bar was born.

It was in Chicago where Frank and Forrest found fortune. They moved the company headquarters from Minneapolis to Chicago in 1929 and built a new factory on the West Side.

“[Forrest] designed it on the outside to look like this fancy, country club-ish, Spanish-style building that you don’t know what’s inside,” Brenner told Chicago Stories. “Forrest did that on purpose. He was really trying to continue in that great tradition of secrecy and protect all of those advances that Frank had developed.”

On the heels of Milky Way’s success in the early 1930s, the company made its next big hits: Snickers, followed by 3 Musketeers. But tension was growing between Frank and Forrest. Forrest wanted to take the company global and continue to expand it, while Frank was happy with the success they already enjoyed. Frank gave Forrest $50,000 and the foreign rights to the Milky Way bar, so Forrest set out to start his own company in Europe and make his own way. There, he developed the Mars Bar, modeled on the Milky Way. Not long after they parted, Frank died at age 50.

Years later, estranged from Mars, Inc., Forrest turned to a competitor of the family business: Pennsylvania-based Hershey. In Europe, Forrest had seen soldiers in the Spanish Civil War snacking on candy-coated chocolates that could be carried without the chocolate melting.

“Forrest was utterly fascinated, and he learned all that he could about how this chocolate became covered or enrobed in a sugar shell. When he got back to the States, he knew that was the product that he was going to introduce to the American market,” Brenner said.

Forrest showed up, unannounced, to meet with William Murrie, the president of Hershey at the time.

“That is what the ‘M’ on the M&M stands for: Mars and Murrie,” said Brenner. Forrest, ever the ambitious businessman, later bought out Murrie’s share. The slogan “The milk chocolate that melts in your mouth, not in your hand” was trademarked in 1954.

6. Frango Mints

You can’t talk about candy in Chicago without mentioning Frango Mints, though technically, the Frango name was not born in Chicago at all. And the original Frango treat was not even a mint – it was a frozen, custard-like dessert with maple flavoring.

“Frango Mints were actually invented in Seattle at Frederick and Nelson department store,” Goddard told Chicago Stories. “When Marshall Field’s bought Frederick and Nelson in 1929, they got the right to the term Frango.”

Following World War II, Marshall Field’s, which had a kitchen in its State Street store, developed Frango Mints, a minty, chocolate truffle. They were marketed as an exclusive indulgence, according to Goddard. And it came at a cost, too.

“When it was first introduced, it was $1.50 a pound, which was a lot for a box of chocolates in the late 1940s,” she said.

It became a “portable symbol” of Chicago, said Goddard, as Frango Mints were often purchased by visitors as a souvenir.

“The fact that Frango Mints are so beloved by Chicagoans is a really good way to tell how well [supposed Frango creator Herb] Knechtel developed a candy that was first of all, delicious, and second of all, very nicely marketed as a Chicago icon. They specifically said, ‘You can buy it only at Marshall Field’s,’” Goddard said.

In 2017, 11 years after Marshall Field’s closed and Macy’s took over, another Chicago classic, touristy treat, Garrett’s Popcorn, purchased the rights to the Frango Mints recipe.

7. Tootsie Rolls

As with Frango Mints, Tootsie Rolls weren’t a Chicago invention, but the company did ultimately end up in Chicago.

Rewind to 1896, when a man named Leo Hirschfield invented the Tootsie Roll in Brooklyn and named the one-cent, hand-rolled candy after his daughter.

Tootsie Rolls were made in New York for several decades until 1968, when company president Melvin Gordon moved operations to a former World War II bomber factory in Chicago. According to the company, they made 64 million Tootsie Rolls every day.

Ellen Rubin Gordon, Gordon’s wife, had a connection to the company before they met. Long before she became president and chief operating officer in 1978, her parents were majority shareholders, and she was once in a Tootsie Roll advertisement. She still runs the company today.

“Who would have known that someday she would be at the helm of Tootsie Roll?” Goddard said. “She’s significant because she was one of the very first women to head up a company being traded on the New York Stock Exchange.”

In its factory near Midway Airport, Tootsie Roll Industries also makes Tootsie Pops, Blow-Pops, Dots, and Junior Mints, among others. One mystery, however, still remains: How many licks does it take to get to the center of a Tootsie Pop? Since 1970, the company has “received more than 20,000 letters from children around the world who believe they have solved the mystery behind how many licks it takes to get to the center of a Tootsie Pop.” The official company position? There are too many variables to arrive at a conclusive answer. “Basically, the world may never know.”