Between 1865 and 1950, there were an estimated 6,500 lynchings in the United States, according to a 2020 report from the Equal Justice Initiative. The violence has been documented since the late nineteenth century, and it was once the topic of a public debate between two of Chicago’s foremost activists.

Journalist and activist Ida B. Wells published a pamphlet in 1892 called Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, in which she investigated 728 lynchings in the South. Months before the pamphlet was published, Wells’s own friends were murdered in a Memphis lynching. But Southern Horrors was merely the beginning of Wells’s anti-lynching crusade – a fight that drew so many death threats and so much rage from Southern whites that Wells was forced to flee Memphis.

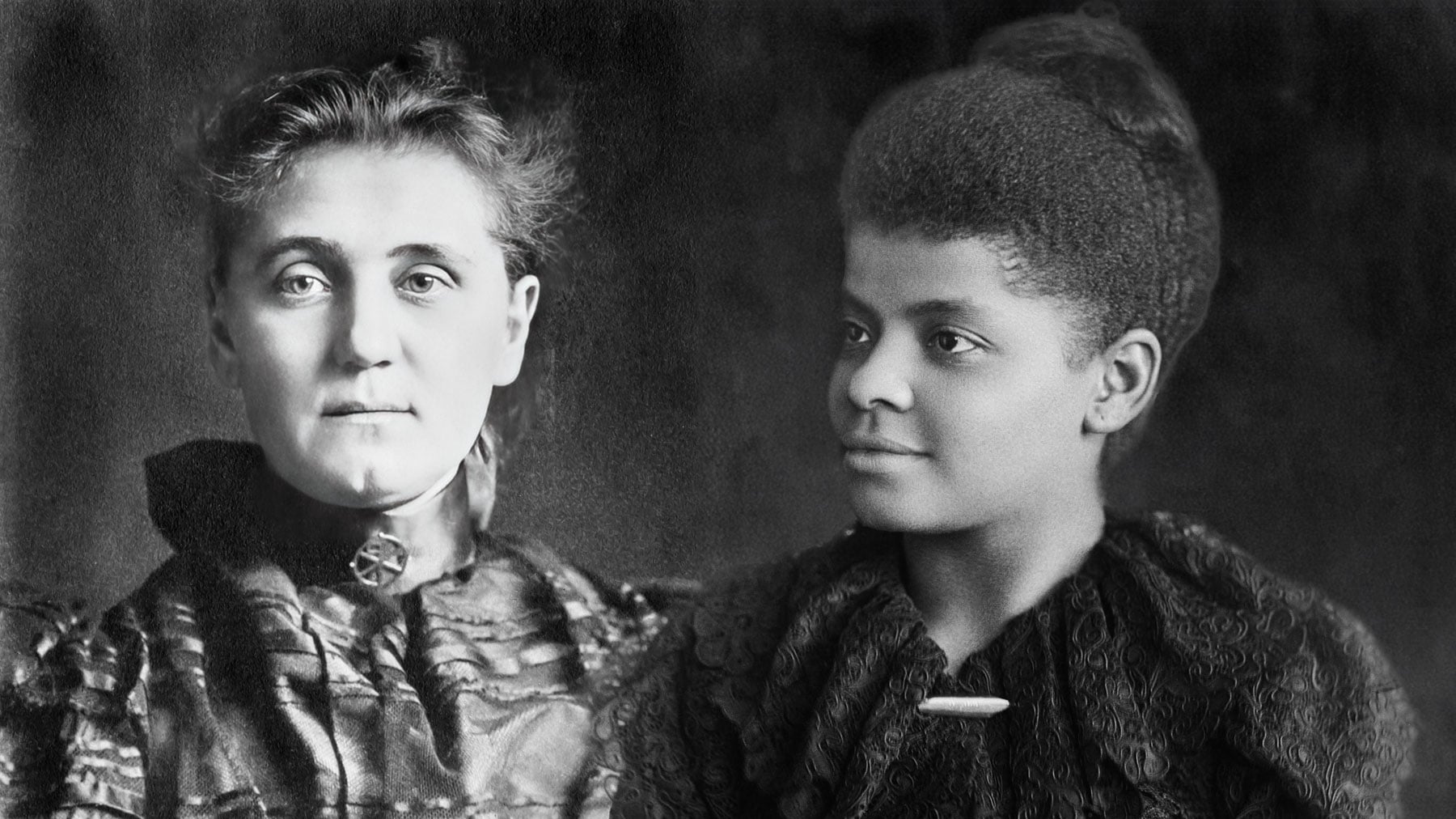

Wells ultimately settled on the South Side of Chicago, just a few years after activist and Hull House founder Jane Addams had moved to the city. Roughly four miles away in the city’s Nineteenth Ward, Addams was working with the city’s immigrant population, advocating for the labor movement, public health, women’s rights, and other issues that emerged from her work in the neighborhood.

The two women were just two years apart in age – Addams, born in Cedarville, Illinois, to an affluent family in 1860, and Wells, born into slavery in 1862 just six months before the Emancipation Proclamation went into effect.

Stacy Lynn, associate editor at the Jane Addams Papers Project, said they likely met in the early 1890s, possibly through their involvement in various women’s clubs in the city. There aren’t many letters between the two, possibly because they lived in the same city, Lynn suggests. Documentation shows that Wells spoke at Hull House on the topic of “social prejudice” in 1898. Addams had an open-door policy at Hull House, and Wells was likely a frequent visitor. In 1899, following the lynching of a Black man in Maysville, Kentucky, Wells invited Addams to speak at a meeting about the violent act.

“Jane Addams is always being called upon to participate in these meetings. She positioned herself through her work [as] a go-to person for all of these various groups,” Lynn said.

Lynn writes that it was Addams’s “first significant connection to the movement for racial justice.” It was that speech that prompted her to write “Respect for Law,” published in The Independent in 1901. In the essay, Addams denounces mob violence, arguing that it undermines the rule of law and due process.

“That violence is the most ineffectual method of dealing with crime, the most preposterous attempt to inculcate lessons of self-control. A community has a right to protect itself from the criminal, to restrain him, to segregate him from the rest of society. But when it attempts revenge…it shows itself ignorant of all the teachings of history.”— Jane Addams, “Respect for Law”

Ross Stanton Jordan, interim director at the Jane Addams Hull House Museum, told Chicago Stories that Addams’s interpretation of mob violence against Black Americans was a common one held at the time.

“If this person did something wrong, what they didn’t deserve was lynching,” Jordan said, describing Addams’s argument. “They deserved a court case. They deserved a fair hearing, but they didn’t deserve a mob.”

But Addams, as Wells would respond, was making one critical error: that the Black people who were lynched were guilty of a crime at all.

“Jane Addams is a white woman working among other elite white women living in a mostly white immigrant community,” Lynn said. “The arguments that she makes are a little less radical, almost always, than Ida B. Wells.”

Ida B. Wells wrote her own essay in direct response to her acquaintance that same year, entitled “Lynching and the Excuse for It.”

“Appreciating the helpful influences of such a dispassionate and logical argument as that made by the writer referred to, I earnestly desire to say nothing to lessen the force of the appeal. At the same time an unfortunate presumption used as a basis for her argument works so serious, tho [sic] doubtless unintentional, an injury to the memory of thousands of victims of mob law, that it is only fair to call attention to this phase of the writer’s plea. It is unspeakably infamous to put thousands of people to death without a trial by jury; it adds to that infamy to charge that these victims were moral monsters, when, in fact, four-fifths of them were not so accused even by the fiends who murdered them.”— Ida B. Wells, “Lynching and the Excuse for It”

Wells’s argument is full of statistics. (A few years prior to this piece, Wells had published The Red Record, which, according to the White House Historical Association, is the first documented statistical report on lynching.) In her rebuttal to Addams’s piece, she writes that hundreds of Black men were lynched for misdemeanors, while others “have suffered death for no offense known to the law,” citing such causes as “mistaken identity,” “unpopularity,” or “insult.”

Wells adds that these reasons far exceed “the lynchings for the very crime universally declared to be the cause of lynching.” The crime Wells is referring to is the assault of a white woman, a prevailing myth at the time that served as the excuse for why Black men were lynched. Wells’s reporting had since proven that to be an “old thread-bare lie.”

“Ida B. Wells thought that was the enormous oversight of Jane Addams, that it further implicated that Black men [had] something wrong with them fundamentally,” Jordan said.

As Lynn points out, Wells’s rebuttal of Addams is very matter of fact but respectful of her colleague, referring to “Miss Addams’s forceful pen.”

“Ida B. Wells doesn’t usually pull punches. She really doesn’t. She will blast people out of the water,” Lynn said. “She doesn't do that with Jane Addams. And I don't think it’s because she’s just being nice to Jane Addams. I think it’s because she respects Jane Addams.”

Lynn thinks it was bold of Wells to call out the influential woman with whom she worked, but that courage is characteristic of Wells, who published reports on lynching amid death threats and whose own printing press was destroyed by a mob for doing so.

“She’s one of the bravest American heroes I think we could ever study. But she also knows that Jane Addams is going to hear her, and so that’s part of it. They work together not too long after that, so there’s no hard feelings over their disagreement on this point,” Lynn said.

There are no letters or other historical documents that provide any insight into what Addams’s response may have been to her colleague’s rebuttal.

“I can't say that Ida B. Wells changed [Addams’s] mind necessarily. But I suspect that Jane Addams gulped and said, ‘Oh yeah, you are right,’” she said.

“[Addams] was a radical in her time in so many ways, but she was what we might think of today as a ‘white liberal,’” Jordan said. “I think Jane Addams would want an advocate like Ida B. Wells to push her, to point out where her democratic ideals weren't meeting all the people that needed support and help.”

Addams and Wells continued to work together. Both women were among the founding members of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Wells also called on Addams for support when the Chicago Tribune published a series of articles “tending to show the benefits of a separate school system for the races in Chicago.” Wells confronted the editor, who made racist remarks to her. Wells turned to Addams, who called a meeting at Hull House and formed a committee to meet with the Tribune.

“I do not know what they did or what argument was brought to bear,” Wells wrote in her autobiography, Crusade for Justice, “but I do know that the series of articles ceased and from that day until this there has been no further effort made by the Chicago Tribune to separate the schoolchildren on the basis of race.”

Nothing excites Lynn more as a historian, she said, than imagining a room in which Ida B. Wells and Jane Addams were working together.

“Holy cow! Those two women being in a room together, solving a problem,” Lynn said. “It’s thrilling to think about. I wish we knew more about their relationship.”