Vietnam Veterans Memorial

Vietnam Veterans Memorial

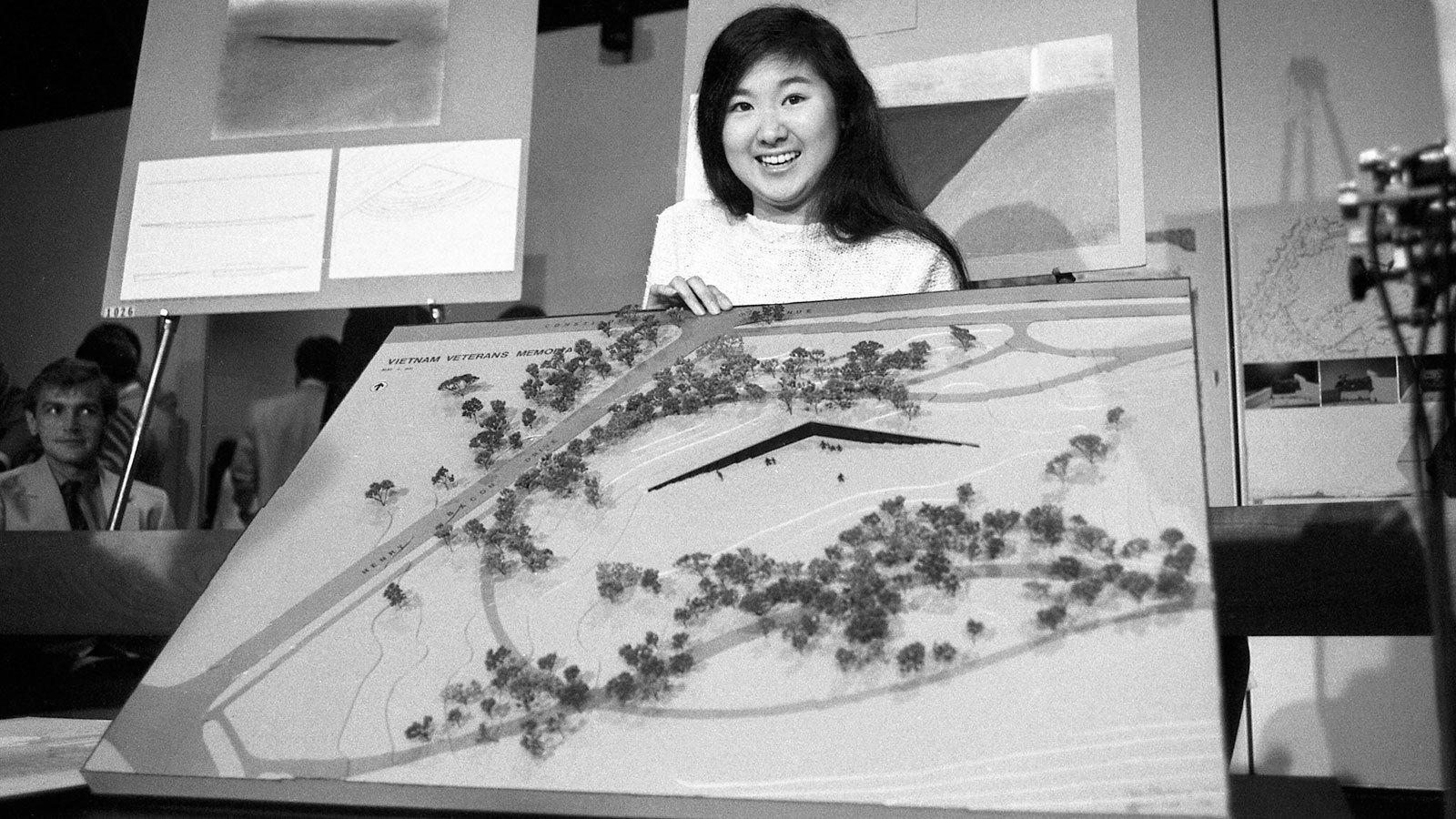

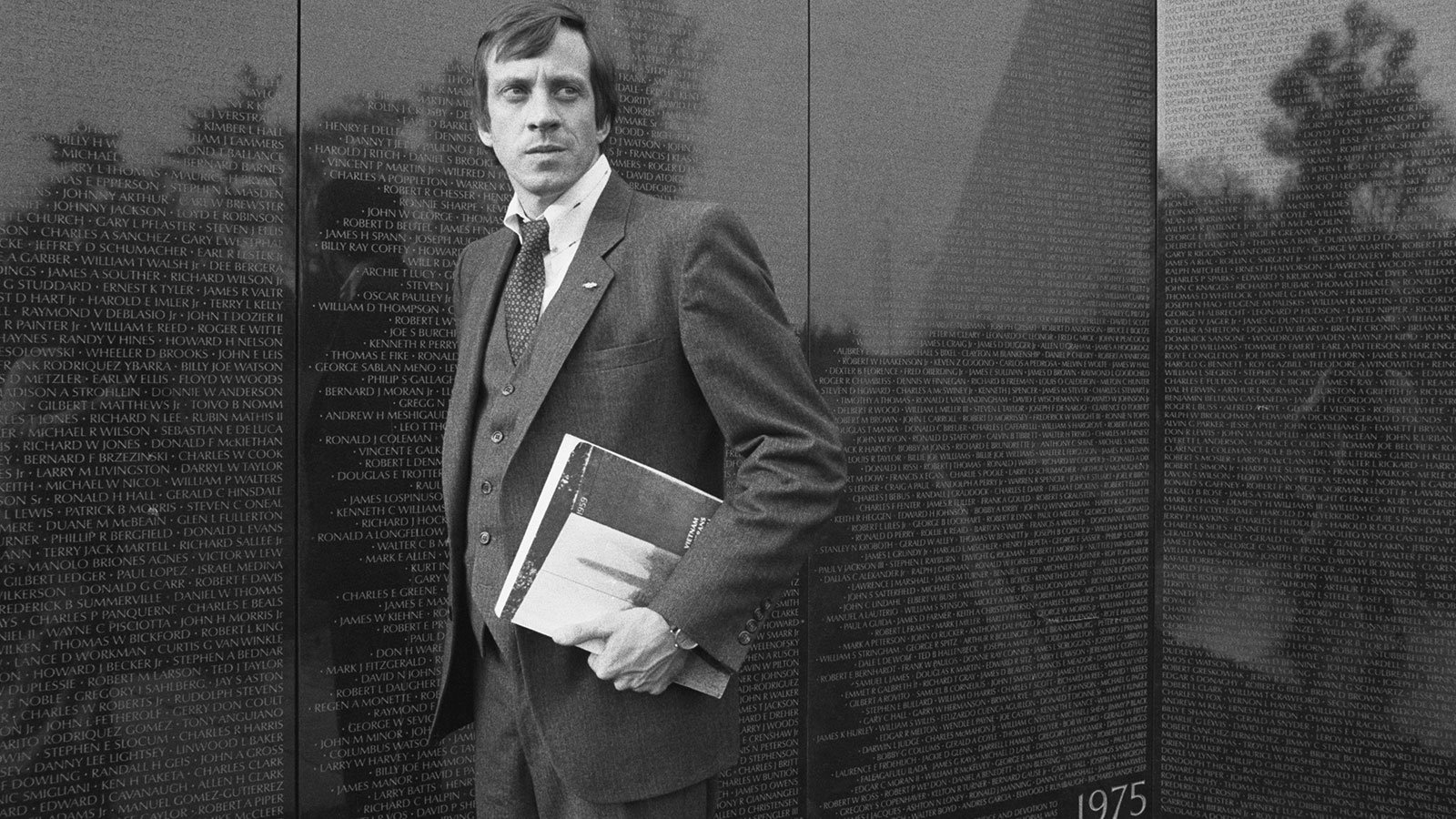

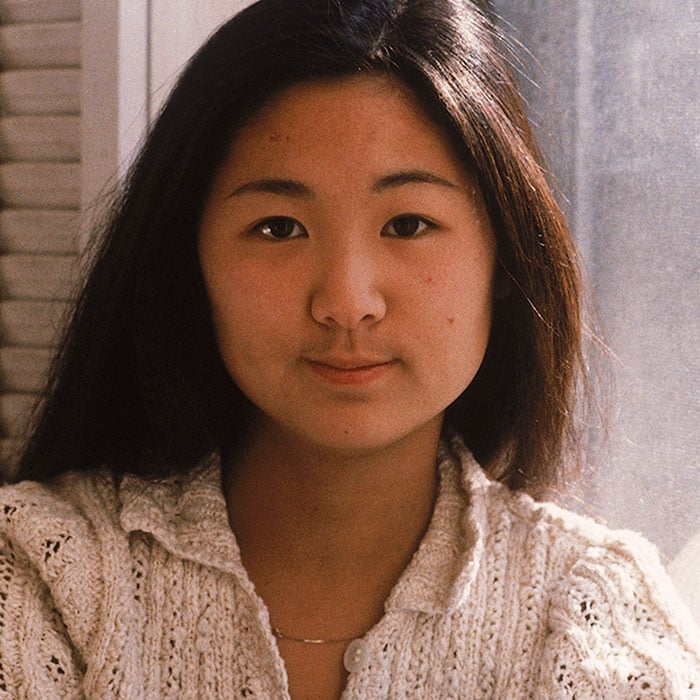

Meet Jan Scruggs, the Vietnam Veteran who led the fight for a national memorial that would heal both his fellow veterans and the nation. The winner of the design competition was an unknown architecture student named Maya Lin, whose design offered an emotional and participatory way to honor the fallen.

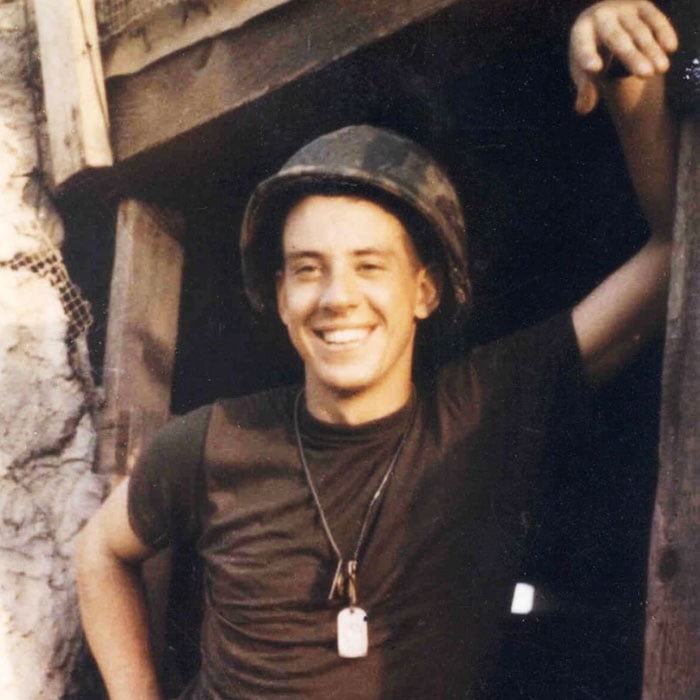

Jan Scruggs was a skinny teenager from Bowie, Maryland, who signed up for the draft, more than anything, to get far away from his hometown. His father, who worked as a cab driver and a milkman, had remarried soon after his parents divorced, and Jan felt like he was in the way.

So in April 1969, he shipped off to Vietnam with the U.S. Army 199th Light Infantry Brigade. He had little concept of how drastically his life was about to change.

During his one-year tour of duty, half of his company was killed or wounded. He almost bled to death in a 1969 mortar attack. It was a lot to handle.

But so was coming home.

“I had kind of a difficult time when I came back,” he said. Public opposition to the war had grown, and he felt like he was the target of their frustration.

“People could not separate the war from the warriors,” said Scruggs. “They misplaced their anger.”

So he tried to numb himself and not think about it. He drank a lot and smoked pot daily.

He says that he definitely suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, which didn’t have a name at the time.

But then he fell in love and got married. He says his wife helped motivate him to get his life together. He enrolled in college and went on to pursue a graduate degree in psychology.

But in 1978, he and his wife went to see the movie The Deer Hunter. The film explored the effects of war – not just on the men who fought it but on their families and communities.

That night, he went home and thought a lot about his own war wounds – not just the shrapnel still in his body, but the memories of what he saw.

The worst of it had happened on base. Some soldiers were returning from combat and unloading ammunition. But someone apparently hadn’t put the firing pins back in the mortar rounds, and a massive explosion was triggered. It was a simple mistake that took a dozen lives.

Jan was shaving at the time and ran out to see what had happened. He recalls seeing one of his friends lying on the ground.

“Their bodies were on fire. One guy, I remember his brains were out of his head,” he said. “You know, all that came back.”

The morning after he recalled all of this, he awoke with an idea.

“I called my boss up,” Scruggs remembers, “and I said, ‘Look, I’m going to build a national memorial in the center of Washington, D.C.’”

His boss laughed it off.

“He said, ‘Well, you know, we all need a mental health day from time to time. Go ahead and take two weeks.’ And he was kind of laughing and everybody was. But I used those two weeks to come up with a theoretical basis that would drive the memorial.”

He began thinking about what he had learned in graduate school about Carl Jung.

“[Jung] had certain spiritual explanations for things,” said Scruggs. “One of the things he talked about was…the collective unconscious and collective psychological states. For example, in a city like Chicago, if the Bears win the Super Bowl, this sort of affects everybody. In…the Vietnam War, the deaths of American soldiers affected everybody, whether they were for the war or against it.”

He wanted to build something that would help everyone heal – the veterans, their loved ones, and the nation.

“The broader benefit that I hoped would happen was that this would sort of serve as a symbol of unity and reconciliation,” he said.

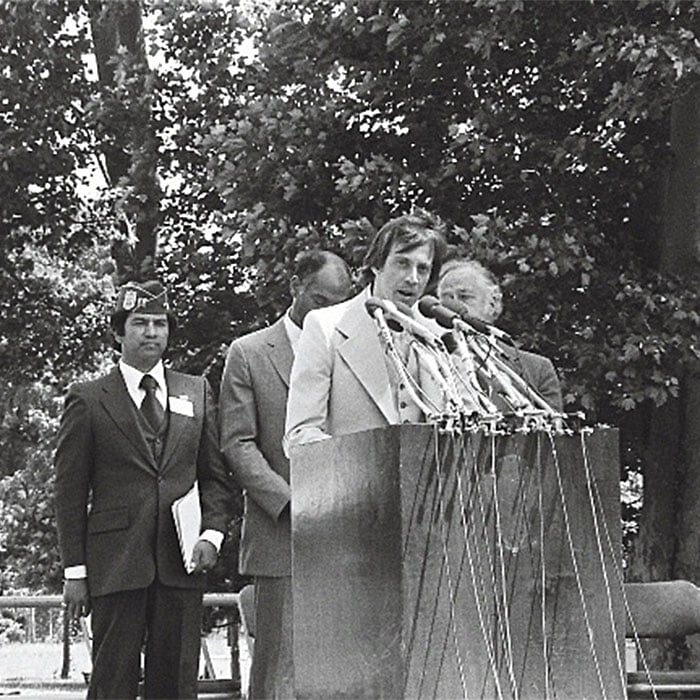

He sold a small cottage he owned in West Virginia for $2,800 and used that money to launch his project. He hired an attorney and held a press conference at the National Press Club in Washington.

With a small group of interested veterans, Scruggs founded the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Fund (VVMF). Soon they enlisted the support of several prominent politicians, from both sides of the aisle.

“I got all these people together to show that this memorial was not about the politics of the war, that this would separate the war from the warrior. And that became our little mantra,” he said.

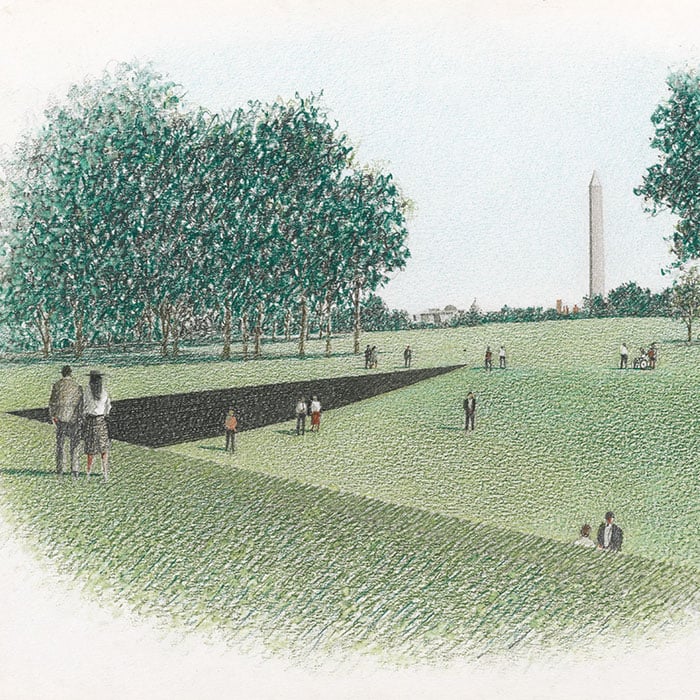

Within three years, the VVMF had raised more than eight million dollars. Congress designated a prime location on the National Mall, adjacent to the Lincoln Memorial.

They announced a national design competition and gathered a panel of leading architects and sculptors as judges. There were only a few stipulations: submitted designs would be contemplative, would display the names of each of the 57,661 Americans who were killed or missing in Vietnam, and couldn’t make a political statement for or against the war.

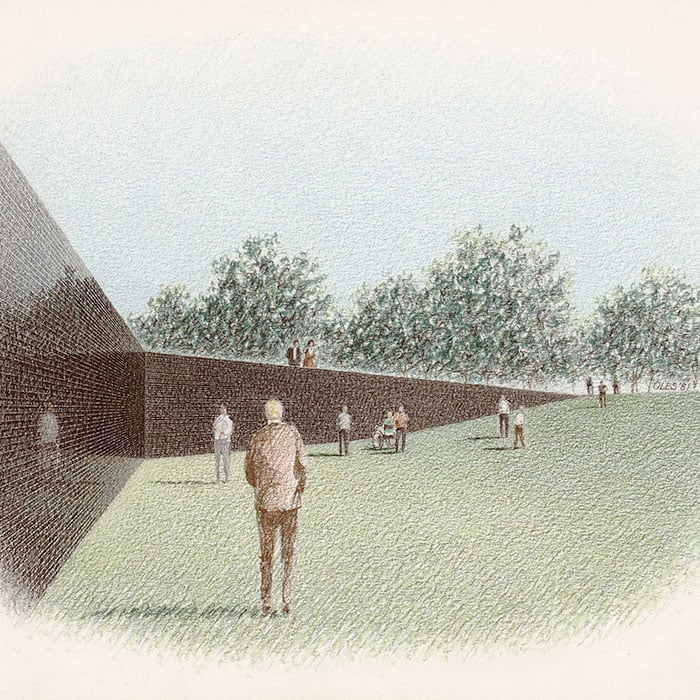

After a blind review of more than 1,400 entries, the jury arrived at a decision. It was a simple design that broke with two centuries of tradition. While most American war monuments were white, soaring, and triumphal, this design would be made of black stone. It would be low to the ground and partially buried. It would be solemn.

“It is completely abstract, it’s a piece of abstract art,” explains architecture critic Reed Kroloff.

“It doesn’t tell you how to grieve; it doesn’t tell you how to celebrate...All of that is open to interpretation.”

The artist turned out to be a total unknown: Maya Lin.

“It was very shocking,” said Kroloff. “She’s not an architect, and she’s not even out of college. She’s a kid, and she’s Asian [American].”

“This is a war where youth died, where young people all across the United States come together to protest this thing. It’s a meaningful choice, by accident,” said Kroloff.

Lin’s age, her race, her gender, and her design were all targets of criticism. Some initial funders withdrew their support.

“This became a Rorschach inkblot [test] for the Vietnam War,” said Scruggs.

But the VVMF stood by their choice, and eventually they won the approval of several prominent politicians and the federal authorities.

But then, says Scruggs, just days before construction was set to begin, an article in the Chicago Tribune about opposition among a vocal group of Vietnam veterans spurred former Congressman Henry Hyde into action.

“Next thing you know, they told our construction crew we can’t build it,” said Scruggs. “We got the money in the hand. We got the approvals, everything we need. [The] secretary [of the] interior says, ‘I’m sorry.’”

Eventually, they all sat down and worked out a compromise. They would move forward with Maya Lin’s design but add two elements nearby: an American flag and a more traditional bronze statue of three soldiers.

The memorial was dedicated on November 13, 1982. Scruggs said the day was filled with “tears, joy, hugs, veterans meeting each other…It all worked, I couldn’t believe it.”

Today, the memorial continues to draw visitors down from street level toward a quiet, contemplative place.

“It allows you to put yourself right up against it,” said Kroloff. “A big memorial on a pedestal, you can’t ever be a part of it. You’re only looking up at it, you’re not ever in it. In this one you’re in the memorial.”

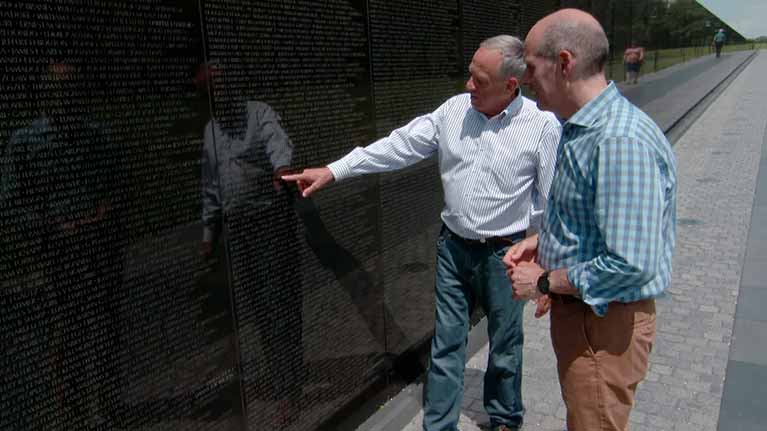

To this day, survivors and descendants leave notes, mementos, and flowers for lost loved ones. They touch the names and make rubbings of the mirror-like granite.

“When you see their names, you see your own face as well, and that’s part of the mystery and majesty of this,” said Scruggs.

Since the memorial’s dedication, additional names have been added, bringing the total number of people lost in the war to 58,272. Other than the more recent additions, the names are not listed alphabetically but by the date they were lost. Men who died together, then, are near each other on the wall.

Jan Scruggs, the driving force behind the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, recounts the ways that the monument has helped him heal his war wounds.

And all of the men Scruggs watched die that day in 1969 are together. It took him almost a decade, though, to seek them out. He was at the wall with NPR reporter and fellow Vietnam veteran Alex Chadwick at the time.

“And he said…’Why haven’t you ever gone to see their names?’” remembers Scruggs. “And I said, ‘I don’t know.’”

And so he did. He touched their names and remembered each of them. He told their stories.

“They didn’t really die for nothing, in one sense, because the tragedy of that, I think, helped create this memorial,” he said.

Today, Jan Scruggs feels good about having dedicated much of his life to creating this place for Americans to remember, to grieve, and to heal.

“You know it’s a pretty awesome thing to get anything done in Washington, even small things. But something that’s 492 feet long and commemorated the people who served in the war who were sort of shunned, to have done something like that…it’s really quite a feeling.”

Scruggs recently retired as the president of the VVMF and battled a heart infection that landed him in a coma. He’s now recovering and continuing to mentor a new generation of veterans from wars in Iraq and Afghanistan who are fighting for their own space where they can honor their dead, grieve their losses, and tell their own story.

“I have one more mission,” he said.