At the age of 29, a Chicago man with piercing green eyes, a talent for drawing, and a pet bird occasionally perched on his shoulder was diagnosed with HIV. Danny Sotomayor, an openly gay man, was one of the tens of thousands of people diagnosed with HIV in the 1980s and ’90s in the United States. During that time, HIV/AIDS was erroneously seen as a “gay disease,” but it did not differentiate its victims. Sotomayor would become one of the loudest voices in Chicago as he fought for his life and the lives of others suffering from a disease that, at the time, was almost a guaranteed death sentence. With his pointed political cartoons, no patience for some of the city’s politicians, and a passionate personality, Sotomayor helped lead major protests that spilled out into Chicago’s streets – and sometimes the balconies of government buildings. Though Sotomayor would not survive his fight with AIDS, his friends and fellow activists remember how he left his mark so that others might survive.

Danny’s Chicago Community

By the 1980s, a section of Chicago’s Lakeview neighborhood that would later be called Boystown had become the center of the city’s gay community. Halsted Street in particular was home to several gay-friendly bars, such as Sidetrack and Roscoe’s, as well as community centers and bookstores, such as Unabridged.

“The bars all had painted windows. There were no signs, there was no flash, certainly no one walked around holding hands or doing anything like that,” Victor Salvo, executive director of the Legacy Project and a friend of Sotomayor, told Chicago Stories. “There was a furtive quality to it, and it lent itself to a subversive quality that gay people ended up really sort of embracing, especially once the politics started to kick in. There was a whole counterculture vibe to it.”

Nearby were the Belmont Rocks, a stretch of the lakefront where queer people could be themselves out in the sunshine at a time when their bars had darkened windows. The gay press, such as Windy City Times and Gay Chicago Magazine, served as platforms for entertainment and editorials.

“I’d been part of a smaller LGBTQ community before, but coming here, it felt like there was so much more to offer. It felt like you were going into the ocean rather than a lake,” author and historian Owen Keehnen told Chicago Stories.

Part of that ocean was a young man named Daniel Sotomayor, known by his friends as Danny. Born in 1958 in Humboldt Park, Sotomayor was of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent.

“He had these vibrant green eyes, and it really stood out because he had dark hair,” his brother, David Sotomayor, told Chicago Stories.

Sotomayor had an abusive father and a troubled childhood. He went to Prosser High School, then on to the American Academy of Art and Columbia College Chicago to get a degree in graphic arts. David said Danny found comfort in drawing. It was a way for him to express himself.

Lori Cannon, a close friend of Sotomayor’s and herself a long-time activist, told Chicago Stories that Sotomayor wanted to escape the abuse of his childhood when he left the neighborhood.

“He wanted to live an openly gay life,” Cannon said. “He had a diverse circle of friends. It was all races. He spoke English to us. He cooked Puerto Rican food. That was his favorite, but he was open to so many cultures.”

He had a variety of jobs, working as a waiter, an actor, and a caricature artist. His pet macaw, George, was sometimes perched on his shoulder. He would later meet his partner, a writer named Scott McPherson. Together they had a dog, a boxer named Scout. Sotomayor was known for his sense of humor.

“It was hanging out at Roscoe’s where I first learned how funny he was,” Salvo said. “He honestly did not have a political bone in his body. It was AIDS that…turned him into an activist.”

In 1981, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) published an article describing a lung infection that was found in five otherwise healthy gay men. Over the next year, more and more healthy men, mostly in New York and California, were infected with the virus. Researchers began calling the new epidemic GRID, or gay-related immune deficiency, inaccurately creating a public perception – and therefore stigma – that it was a “gay disease.” The CDC first began using the term AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, in September 1982. From 1981 to 1990, more than 100,000 people died from AIDS-related illnesses, according to the CDC, with hundreds of thousands more infected.

“In most people’s minds, they were inseparable: AIDS and homosexuality were the same thing,” Salvo said.

Though case counts were much higher in New York and California, many Chicagoans remember it as a frightening time. There were few resources for people living with HIV/AIDS, and little to no money was going toward funding research and treatments. In the early years, people didn’t know what caused the illness or how it spread. Bill McMillan, former AIDS activist and friend of Sotomayor, told Chicago Stories that he remembers one bar on Halsted Street using plastic cups for fear of germs spreading.

“There was a lot of shame,” McMillan said. “It [added] another layer of shame to being a homosexual. It was very different back in 1983 than it is today.”

People diagnosed with AIDS were sometimes evicted from their apartments, dropped from their insurance, and fired from their jobs. Keehnen said that in addition to the stigma, there was a lack of compassion and sense of urgency for those who were sick. He said he often saw sick people come into Unabridged Bookstore, where he worked at the time.

“There were so many people who had come in, and they would be ill. And then you would see them in a couple weeks, and they’d look a little…sicker and then you wouldn’t see them anymore, and then they’d be dead. And that happened over and over again,” Keehnen said. “All you saw was loss of potential…My anger came from just seeing so many people who, all they wanted to do was stay alive. That’s all they wanted.”

For many people living with AIDS, it wasn’t a gradual illness. Some got a head cold and died within weeks. It exposed the vulnerability of a community who largely lived their lives in the shadows, said Salvo.

“When I was 29 years old, I didn’t know a single person who was HIV positive. By the time I turned 30, six of my friends were dead.”— Victor Salvo

In 1987, Sotomayor was diagnosed with HIV. By 1988, Sotomayor’s illness had turned into full-blown AIDS. He spent the next several years in and out of hospitals for different illnesses caused by the virus.

“It was a death sentence: ‘Plan your funeral,’” said activist Rick Garcia of receiving such a diagnosis. Garcia said some people became depressed and retreated from society. Others, such as Danny, got angry. The stigma and the lack of urgency and resources fueled the anger.

“That rage he felt as a child and young adult quickly got transferred to his activism while he started fighting for everybody’s life, including his own,” Cannon said.

Danny’s Fight

In 1987, the inaugural display of the AIDS Memorial Quilt took place in Washington, D.C., on the National Mall. The following year, the quilt came to Chicago. The sight of the quilt – each panel representing a human life lost to AIDS – unlocked something in Sotomayor.

“Danny said, ‘That’s going to be us one day. But we’re here now. Let’s make our time count,’” Cannon said.

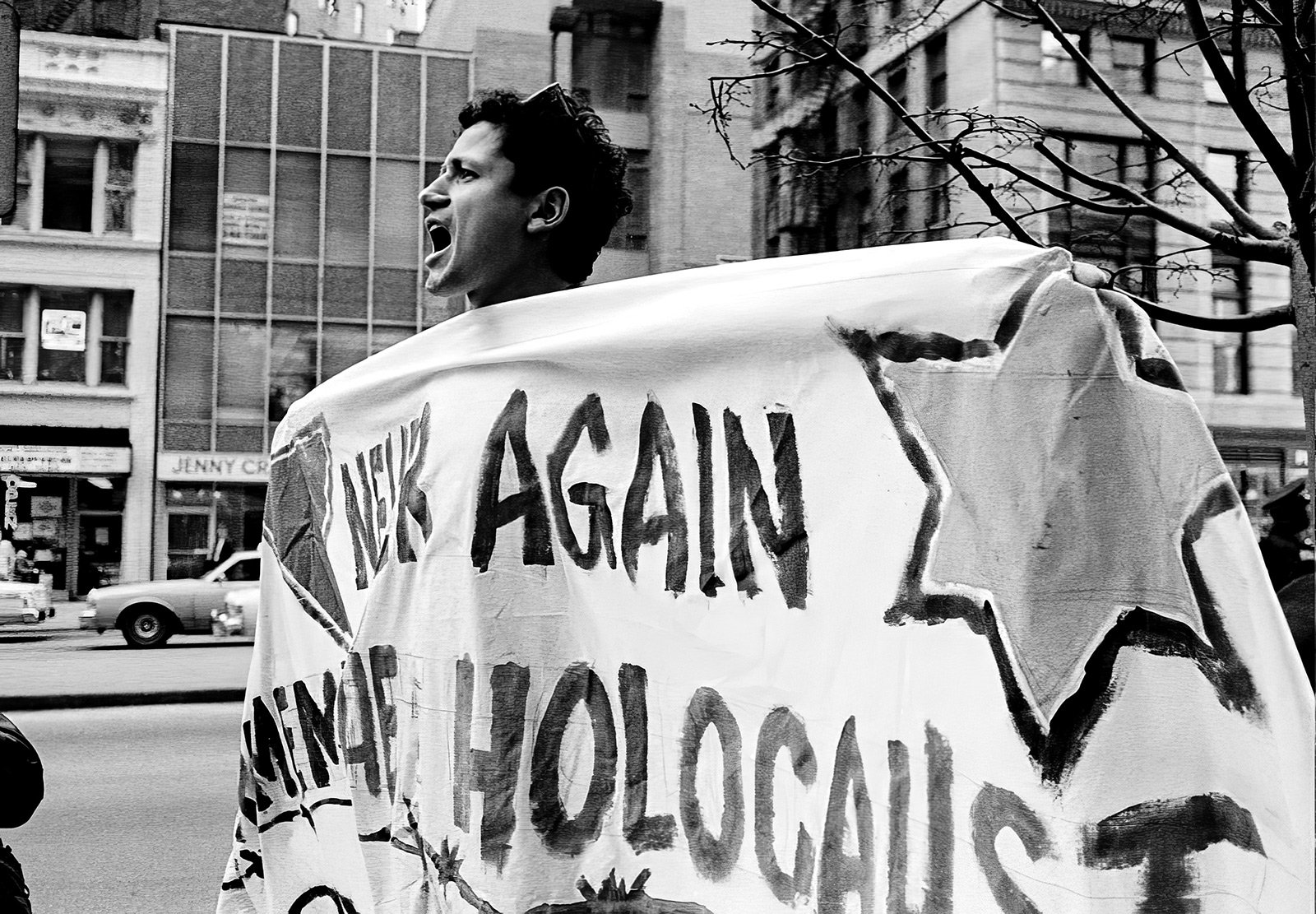

Sotomayor became more involved with AIDS activism while visiting the quilt on display in Washington once again in the fall of 1988. A group called the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP, had also staged a protest at the Food and Drug Administration calling for the approval of azidothymidine, or AZT, the only drug known at the time to inhibit the progression of AIDS. Sotomayor attended the protest.

“One of the most frustrating things about AIDS and HIV prior to this was the lack of attention on anything. ACT UP learned how to use the media, how to market themselves…to change the narrative that was causing death,” Keehnen said.

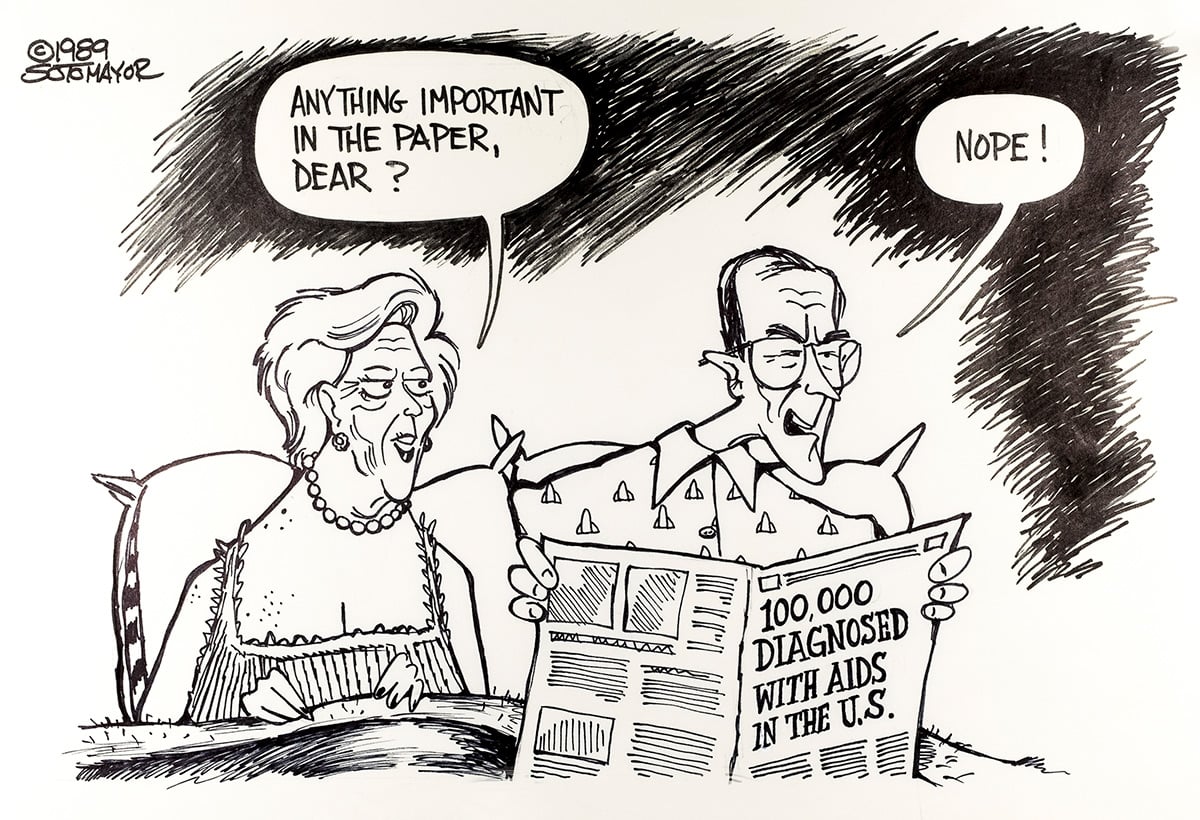

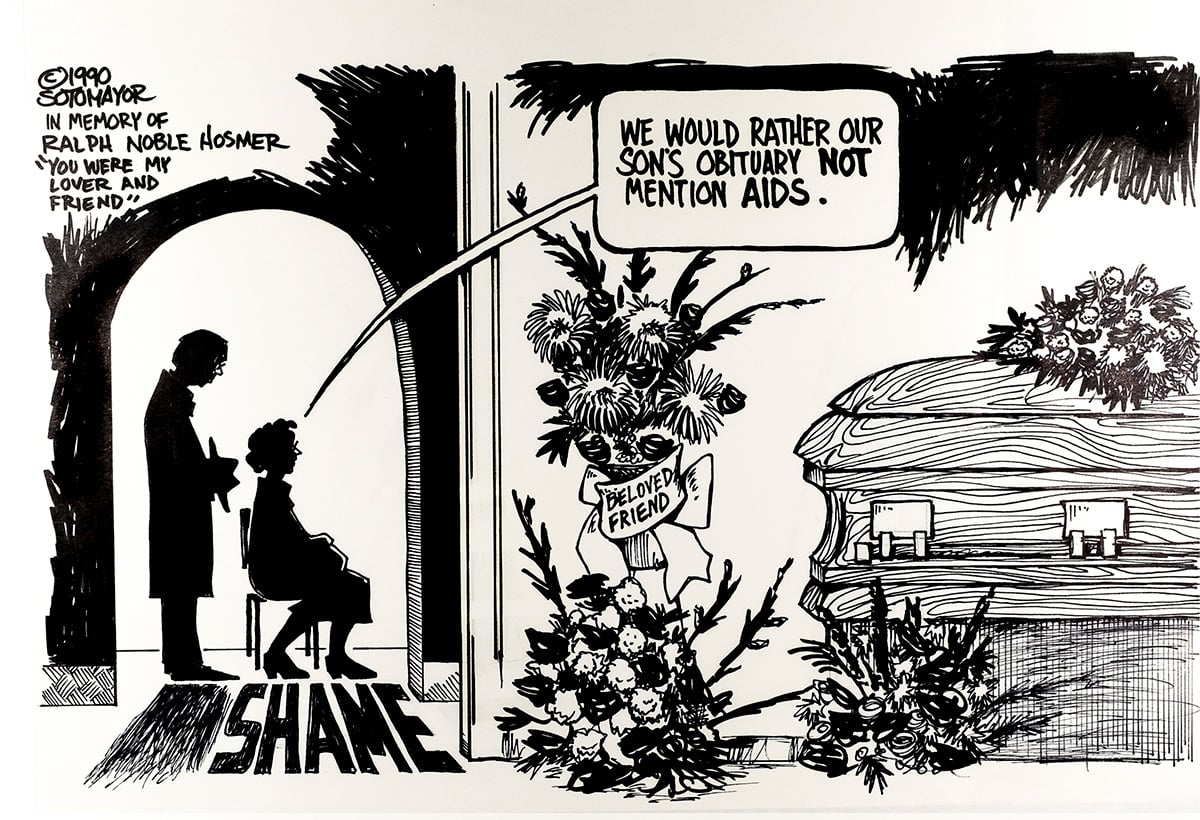

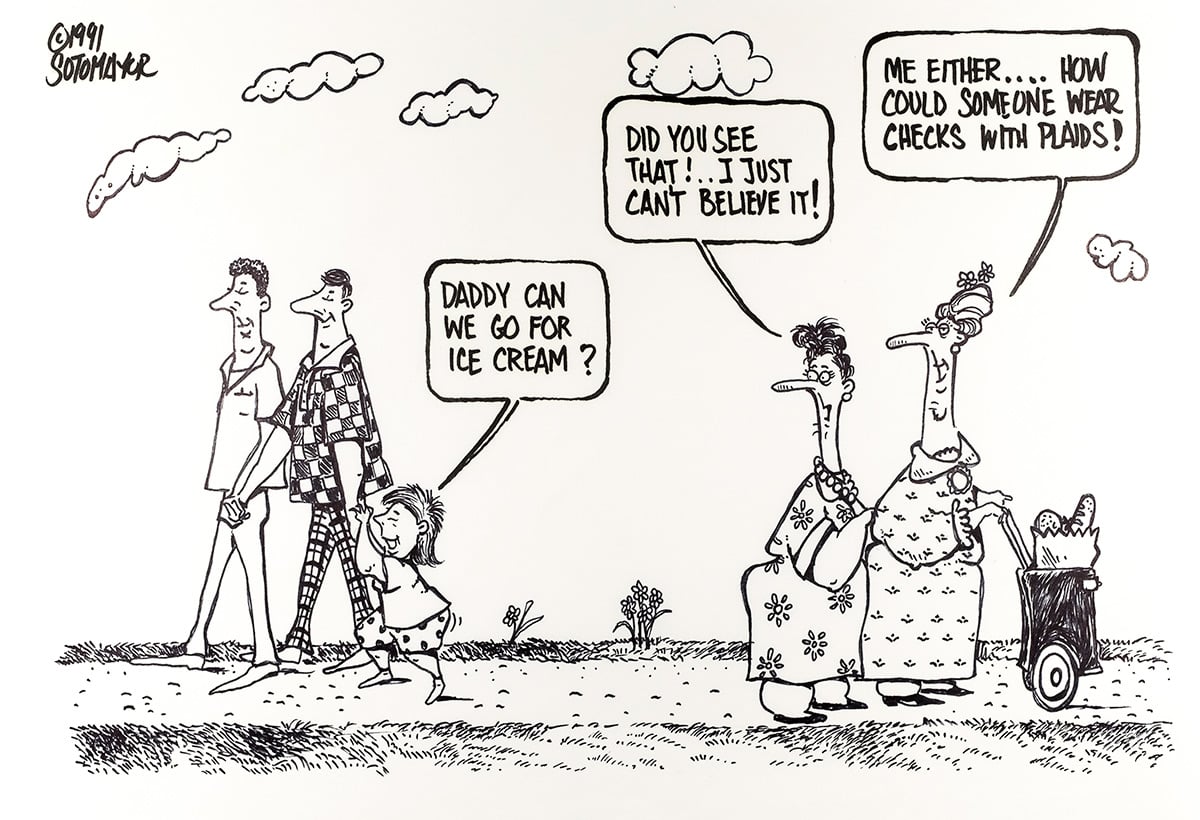

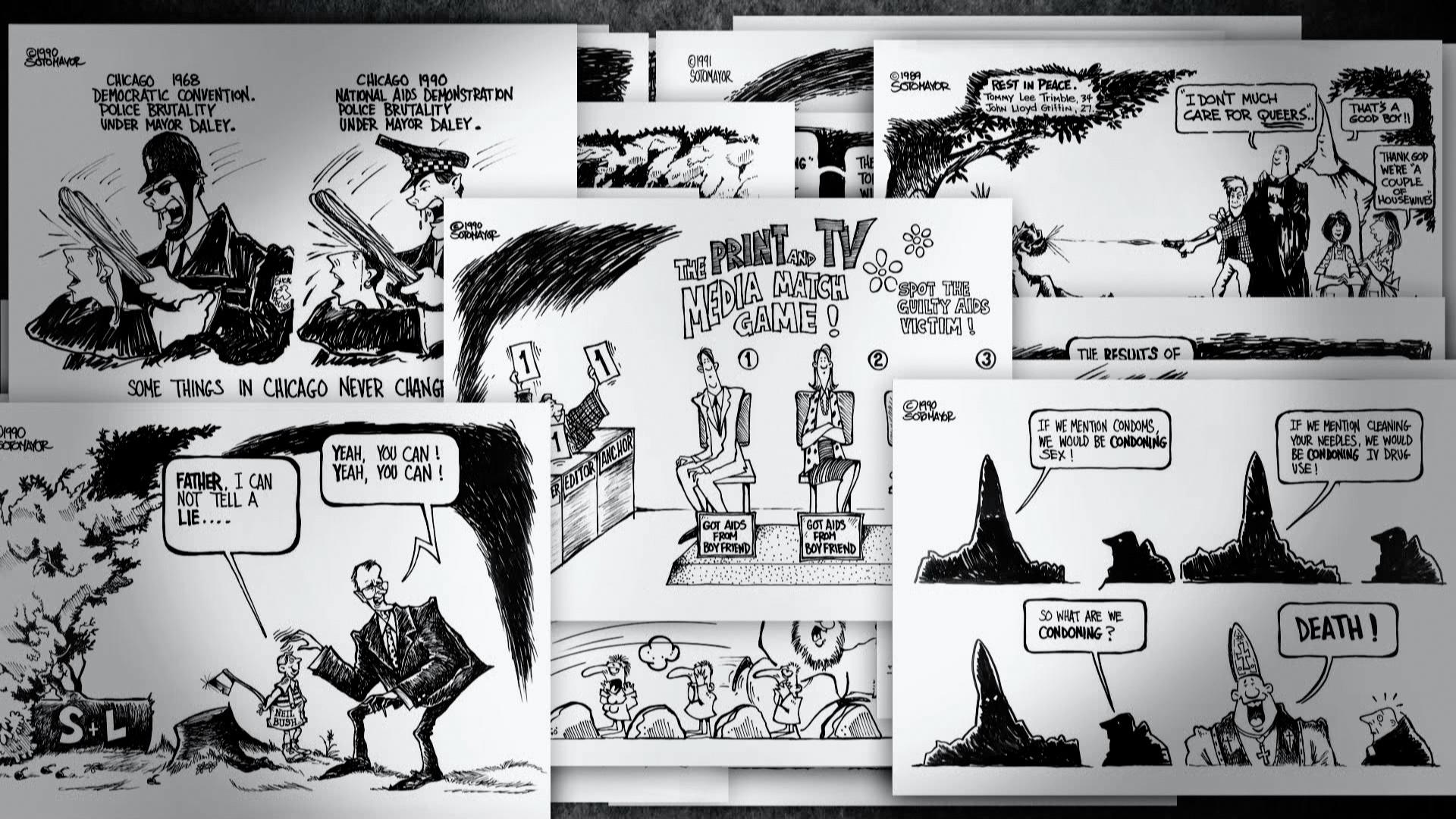

After that protest, Sotomayor got involved with the local chapter, ACT UP/Chicago, which evolved in the late ’80s from various other LGBTQ rights and AIDS organizations and went on to lead several protests in the city. He also used his talent for drawing to create pointed political cartoons that were published in the local gay press. He later became the first openly gay, nationally syndicated cartoonist, with his work appearing in newspapers across the country.

His cartoons often went after politicians, insurance companies, or pharmaceutical companies. What made his cartoons special, Cannon said, was that they came from the pencil of a man living with AIDS.

“They were honest, and they were his viewpoint [with] no sugarcoating, no soft-pedaling,” Cannon said. “Even when he was sick, he found a way to get something in.”

Cannon said one day while riding the ‘L’ with Sotomayor, they noticed a CTA advertisement depicting a condom and the phrase, “Don’t think of it as birth control. Think of it as death control.” Sotomayor was angry, believing the ads to be blaming individuals with HIV. He wanted ads that were informative about safe sex at a time when education about HIV/AIDS was nonexistent. Salvo said the ads featured only heterosexual people “because you weren’t allowed to spend any money on anything that validated homosexual existence.” ACT UP/Chicago took action.

“We contacted [the] CTA and asked them to meet with us several times to talk about these posters,” McMillan said. “They would have nothing to do with us.”

Sotomayor put his skills as an artist to work, creating his own CTA advertisements. One showed a dancing condom and read, “Don’t be silly, wear a willy.”

In May 1989, a group from ACT UP/Chicago got together at a CTA bus stop at Clark Street and Diversey Avenue. Several of the activists boarded buses to post the new advertisements, while others staged a “die-in” – a person would lie down in the street and another would outline their body in chalk to represent the death toll – in the middle of the intersection. McMillan estimated that 15 to 20 people were arrested, and some went out to a Mexican restaurant to celebrate after they got out of jail. Keehnen said direct action felt therapeutic.

“Demonstrations were screamed therapy, and it was screamed therapy in a community. It was just this massive release of anger and just this cry for change. It was incredibly empowering.”— Owen Keehnen

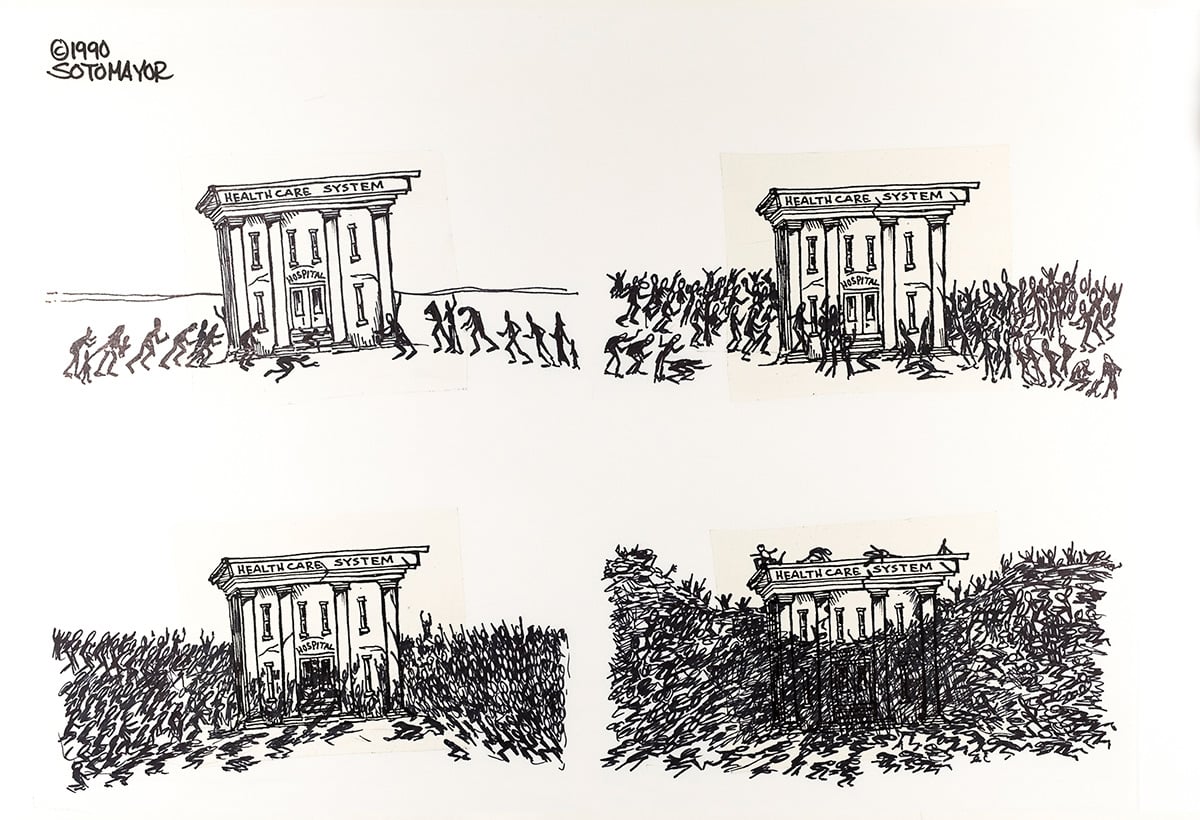

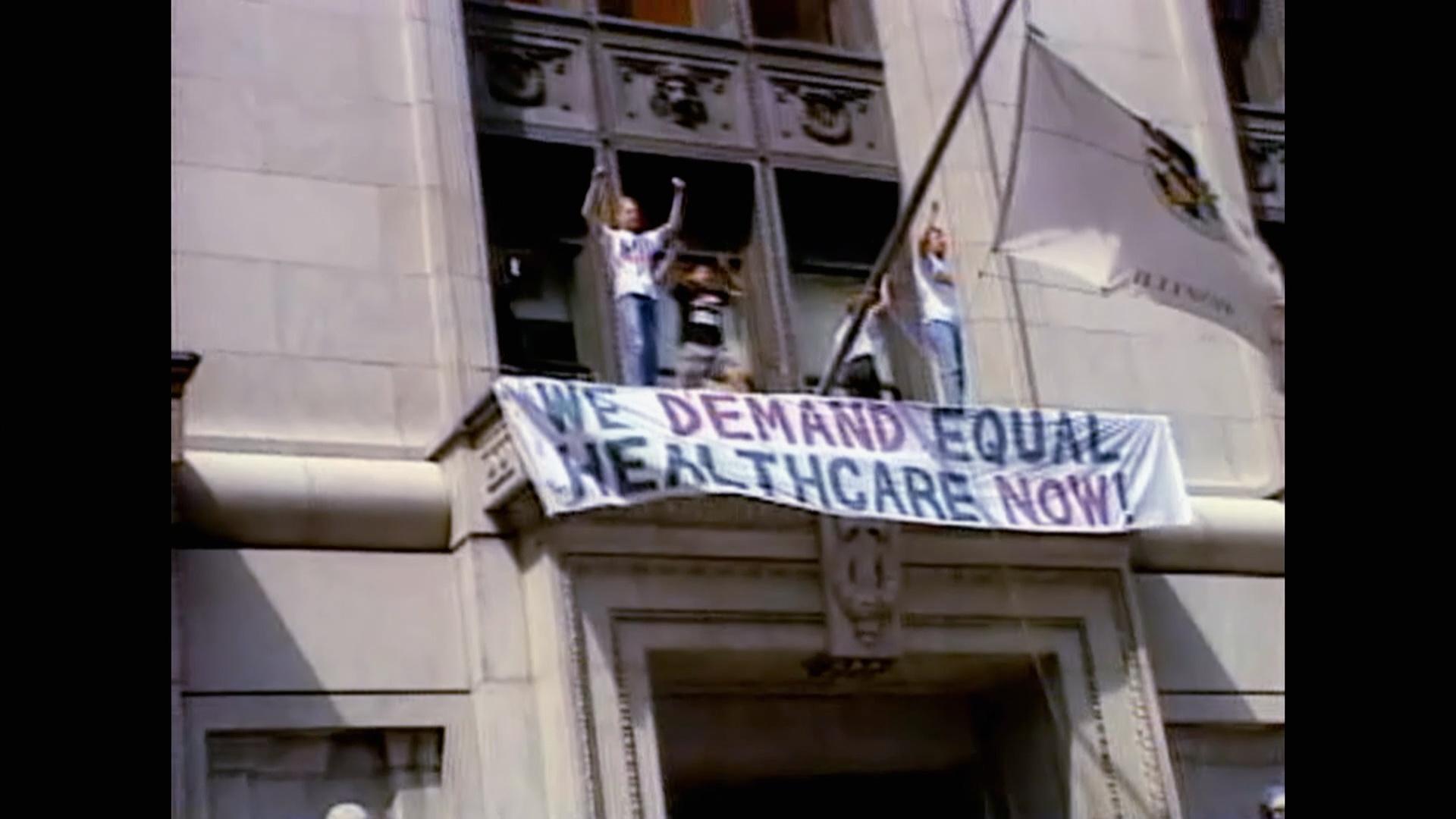

Eventually, the CTA pulled their “death control” ads. ACT UP/Chicago continued that release of anger, organizing a large event called the National AIDS Action for Healthcare in 1990 with thousands of people protesting the denial of insurance coverage to LGBTQ people, the high cost of medication, the slow pace of drug trials, and the lack of an AIDS ward for women at Cook County Hospital.

The National AIDS Action for Healthcare march started at the Prudential Building, then headed toward the American Medical Association. Chicago police were there, some on horseback, some wearing rubber gloves. Some of the women of ACT UP/Chicago had hidden mattresses in an alley, and then threw them down in the middle of the intersection of Washington and LaSalle streets to represent the lack of a women’s AIDS ward.

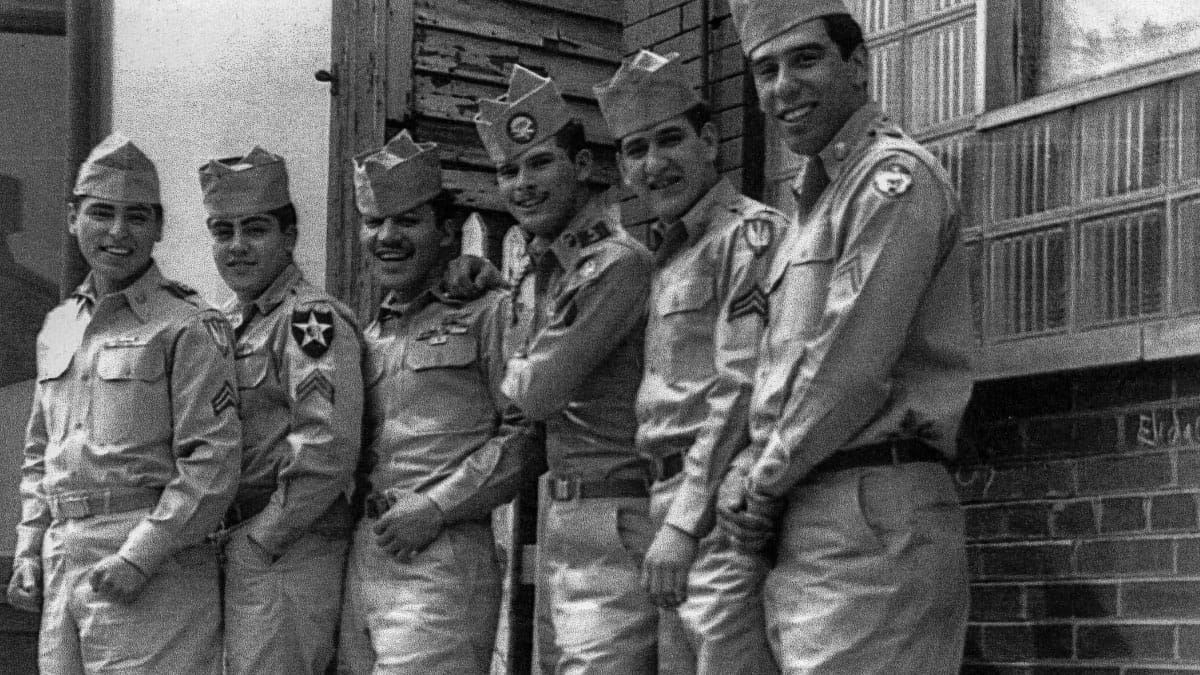

While people were consumed by the mattress stunt, Sotomayor and four of his friends – Bill McMillan, Tim Miller, Frank Sieple, and Paul Adams – slipped away and headed for the County Building. They calmly walked into the building, dressed in nice dress shirts, and boarded an elevator. They entered an office.

“There was this middle-aged woman sitting there, and she said, ‘Can I help you?’ And we said, ‘No.’ We just walked right by her,” McMillan said. They went into an inner office, blocked the door with a heavy desk, and climbed out onto a balcony that overlooked the street. They removed their dress shirts to reveal their ACT UP/Chicago t-shirts and unfurled a large banner that read, “WE DEMAND EQUAL HEALTHCARE NOW.” The crowd below cheered.

“It was just very, very empowering. It was electric,” McMillan said. “Everybody is seeing this. We’re getting our message across.”

Some of their friends below were worried, because there was no railing and they were high off the ground. Because they were on the county side of the building, it took a while before the county sheriff’s officers arrived. They dragged the men in one by one, with Sotomayor and Adams as the holdouts.

“Danny was on the balcony and he was saying, ‘I’m a person with AIDS. I don't have anything to lose. If you don’t get away from me, I’m gonna jump,’” Keehnen recalled. The demonstration, he said, “was so operatic. It was larger than life.” It propelled Sotomayor forward as one of the most visible leaders of the AIDS movement in Chicago.

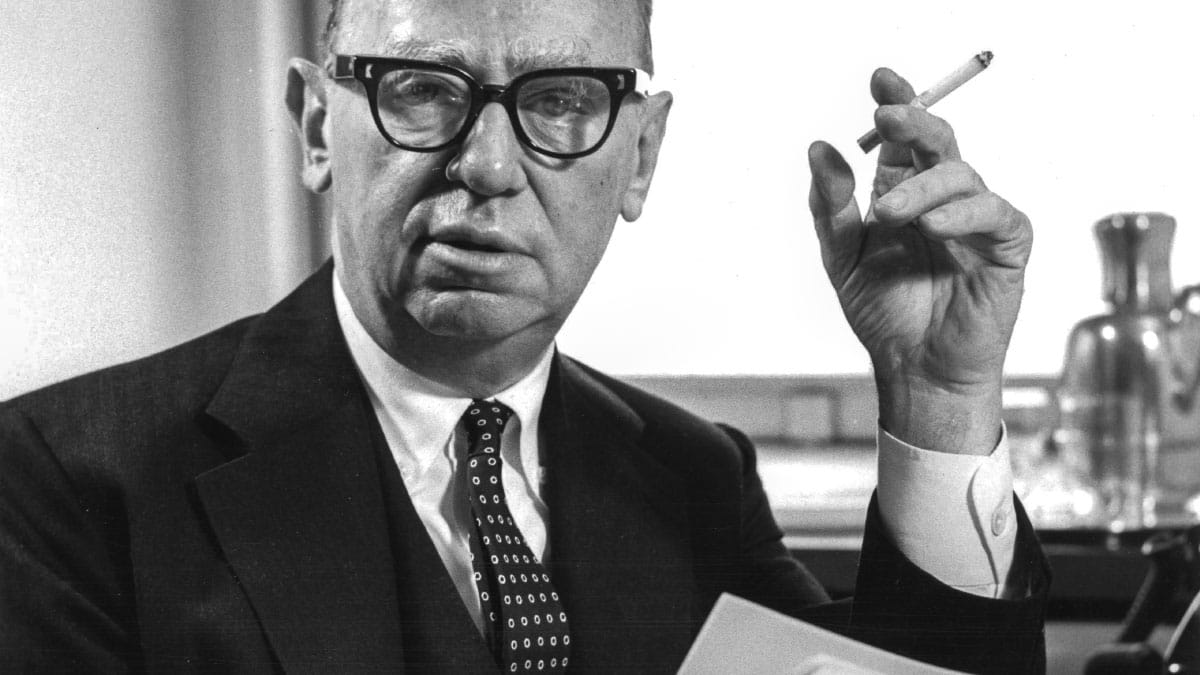

As that visible leader, Sotomayor often went head-to-head with another leader in Chicago: Mayor Richard M. Daley. Daley had assumed office in 1989, and Sotomayor made it his mission to target Daley and his AIDS policies. The city budget included very little AIDS funding. McMillan said that activists learned from a former city employee that more money was going to rat abatement in the city than for AIDS funding.

Activists clashed with Daley at a meeting at Ann Sather’s restaurant in Lakeview. One activist accused Daley of having no compassion for people living with HIV/AIDS.

“[The comment] had something to do with someone asserting to Daley that he had no idea what it felt like to lose someone. And Daley had very recently lost a child to spina bifida,” Salvo said.

The meeting did not go well. Daley stormed out of that particular meeting, but Sotomayor would follow him to other places around the city in the months that followed. He frequently showed up at Daley’s press conferences and other events, often blowing a whistle and flashing a sign reading, “DALEY TELL THE TRUTH ABOUT AIDS.”

Over time, some of the insurance companies, government entities, and hospitals began to respond to the demands for change as the AIDS crisis wore on. ACT UP/Chicago wanted to adapt and expand its strategy to focus on groups beyond gay men who were living with HIV/AIDS, such as women, incarcerated people, or people using intravenous drugs. Sotomayor and ACT UP/Chicago eventually parted ways over their different approaches.

But Sotomayor continued being a vocal – albeit solo – protestor, continuing to show up at events with Daley. In 1991, a gay and lesbian political action committee called IMPACT held its annual gala. Daley was in attendance. Unfortunately for Daley, so were Sotomayor and Cannon. Cannon had volunteered to greet people, allowing Sotomayor (who was not on the guest list) to enter. When Sotomayor spotted Daley, they were “nose-to-nose.”

“The banner is now out of my purse. I have my whistle and there’s a mini-action. It’s caught on camera. And at that point they call security and [we’re ushered out],” Cannon said. “That is what prompted Mayor Daley to make that famous quote, ‘Why is that kid always yelling at me?’ At which point [local activist] Kathy Osterman responded, ‘That kid has a name. It’s Danny Sotomayor. Do you ever listen to what he says?’”

Those bold actions sometimes put Sotomayor at odds with his fellow activists.

“I would say if he was passionate about an issue, it became very hard to convince him that there was any other way to approach it than the way he viewed it,” Keehnen said.

Sotomayor lost his cartoon gig with Gay Chicago because he had used a fake press pass to infiltrate a press conference with Daley. He also lost a cartoon job with Windy City Times for once again blurring the line between his activist and editorial roles. Salvo said Sotomayor’s rebelliousness came from his impatience as AIDS “continued its march” through his personal life and health and as he continued going through a health care system that did not yet have the infrastructure to support people with AIDS.

“Danny was always biting the hand that fed him,” Salvo said. “He went through this personal transformation from being this quiet, nice guy with a really kooky sense of humor to this firebrand.”

Danny’s Legacy

By the end of 1991, both Sotomayor and his partner, Scott McPherson, were sicker. At the next year’s IMPACT dinner, they were both in the hospital. Their beds were close enough to hold hands, former ACT UP/Chicago member Sharyl Holtzman told Chicago Stories. But the same event Sotomayor had interrupted the year before was now giving him an award for his tireless activism. Though Sotomayor was too ill to leave the hospital, Cannon and Salvo were able to take McPherson to see Sotomayor honored at the dinner. When they brought McPherson back to the hospital, he spoke to Sotomayor.

“Scott was like, ‘You should have been there, Danny. They were all applauding for you. They were all cheering for you,’” Salvo said. “You kind of hope he heard it.”

The dinner was on February 2, 1992. Danny Sotomayor died as the sun was rising on February 5. Thousands of people came to his wake. Much to the shock of his friends, Mayor Daley showed up.

“I don't know which one of us said it first. It was probably me. ‘Well, you know for sure he’s dead because he’d be sitting up strangling [Daley].’ That was the proof right there,” Salvo said, laughing.

Sotomayor’s family, who was sometimes in conflict with his friends in his remaining days and after his death, had a Catholic mass for his funeral. Salvo said if there was anything Danny hated more than Mayor Daley, it was the Catholic Church. His friends later put together a memorial service at the Riviera Theatre. Salvo put together a slideshow of images to David Bowie’s “Heroes.”

Though Sotomayor was gone, his friends and fellow activists continued fighting for people with AIDS. Increasing Chicago’s budget for AIDS support, for which Sotomayor had long fought, was still a top priority. Someone within the Daley administration had leaked the city’s proposed budget to leaders at ACT UP/Chicago. The activists then put together their own proposal which they shared with Alderman Helen Shiller. Shiller drafted a spending proposal that the Daley administration supported. The city had tripled its spending on AIDS.

Just four years after Sotomayor saw the AIDS Quilt at Navy Pier, his friends created his own square in his memory, adding his name to what would ultimately become 110,000 names stitched into its panels. His square, designed by Salvo, showed his famous cartoon critiquing George and Barbara Bush, with photos and written remembrances from his friends. McPherson, who would die in November 1992, was able to write his name and a love letter to Sotomayor on the square.

Since the beginning of the crisis, 675,000 people with AIDS have died, according to the CDC. But better treatments and funding have no longer made such a diagnosis a death sentence. Thirty years after Sotomayor’s death, his friends remember his tenacity. He was inducted into the Chicago LGBT Hall of Fame and now has a plaque on Halsted Street’s Legacy Walk, which is led by his friend Salvo.

“At a certain point, Danny wasn’t fighting for himself anymore,” Keehnen said. “He was fighting more for the people in the future.”

One of the last things Sotomayor told his brother, David, as he was dying was that his brother would miss him six months from now.

“He was absolutely right,” David Sotomayor said. “Well, he was actually wrong about the six months. It’s been 30 years.”