By 1880, business was booming for George Pullman. Production of his famous sleeper cars was ramping up, and the draftsmen, carpenters, painters, and other laborers who helped him build that empire were hard at work.

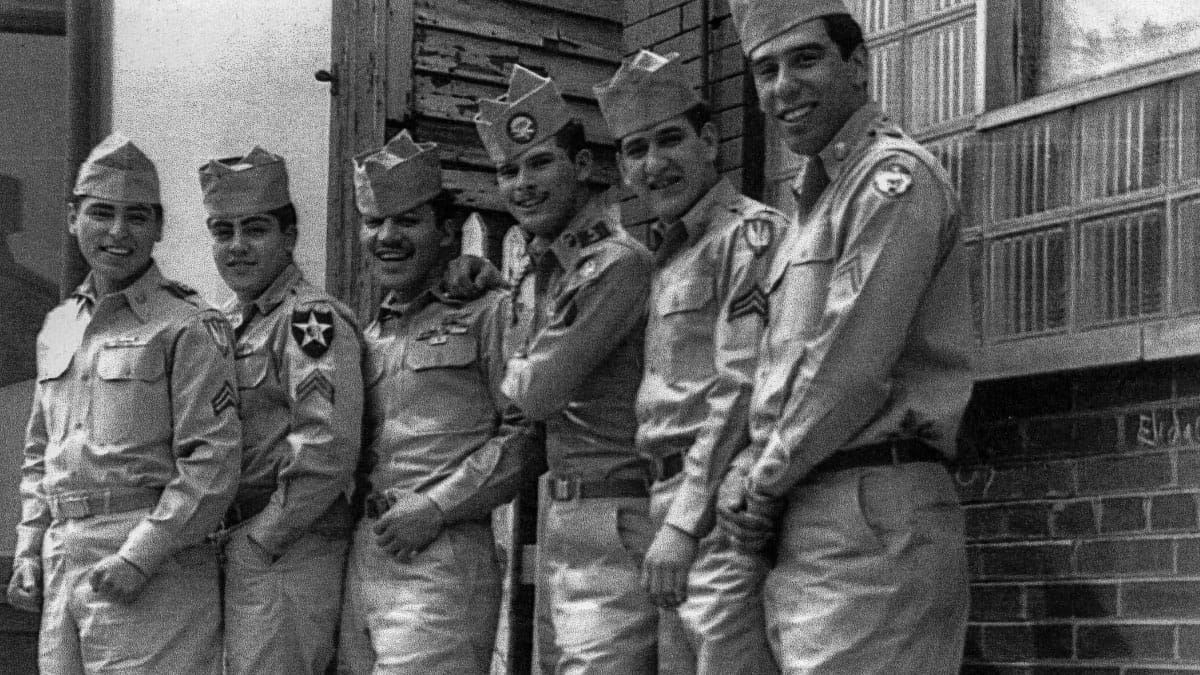

At a time when there were few workplace protections for people working even the most dangerous jobs, Pullman wanted a way to instill a sense of loyalty in his factory employees, many of whom were European immigrants.

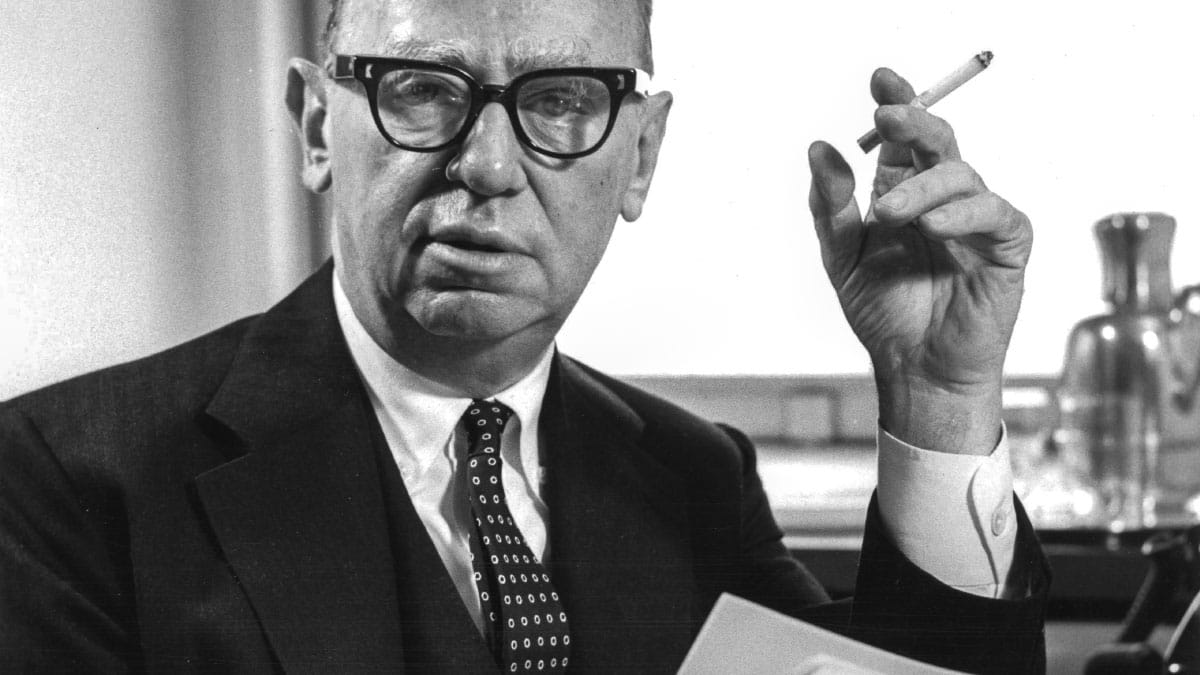

“Maybe we don’t want to kill them in the workplace because we want them to come back. Maybe we don’t want them living in squalor where they could suffer disease because we want them to come back,” Bob Bruno, professor of labor and employment relations at the University of Illinois, told Chicago Stories.

So he built an eponymous town where he would provide everything his workers needed, at least on the surface.

Pullman purchased 4,000 acres of land south of Chicago near Lake Calumet and built a planned company town where his employees could live comfortably in a nice, clean town with the added bonus of being close to his factory.

“He hoped that it would be capitalism helping labor equally, while labor helped capitalism,” Sue Bennett, assistant superintendent of the Pullman National Monument, told Chicago Stories. “It was an opportunity to improve their lives by having a more pleasant landscape around them with amenities, social clubs, and organizations.”

According to the National Park Service, the town of Pullman was ethnically diverse, with fewer than half of the residents in 1885 being native-born Americans. Many were English, Dutch, German, Irish, and Scandinavian. Though the Pullman Company employed Black men and women to work as porters and maids, the town itself had very few, if any, Black residents. The porters and maids typically lived in Bronzeville, closer to downtown Chicago, or near the rail lines.

“The company itself actually had no restriction on race [when it came to] who would live in the town of Pullman,” Bennett said. “But let's face it: There were societal limitations based on race.”

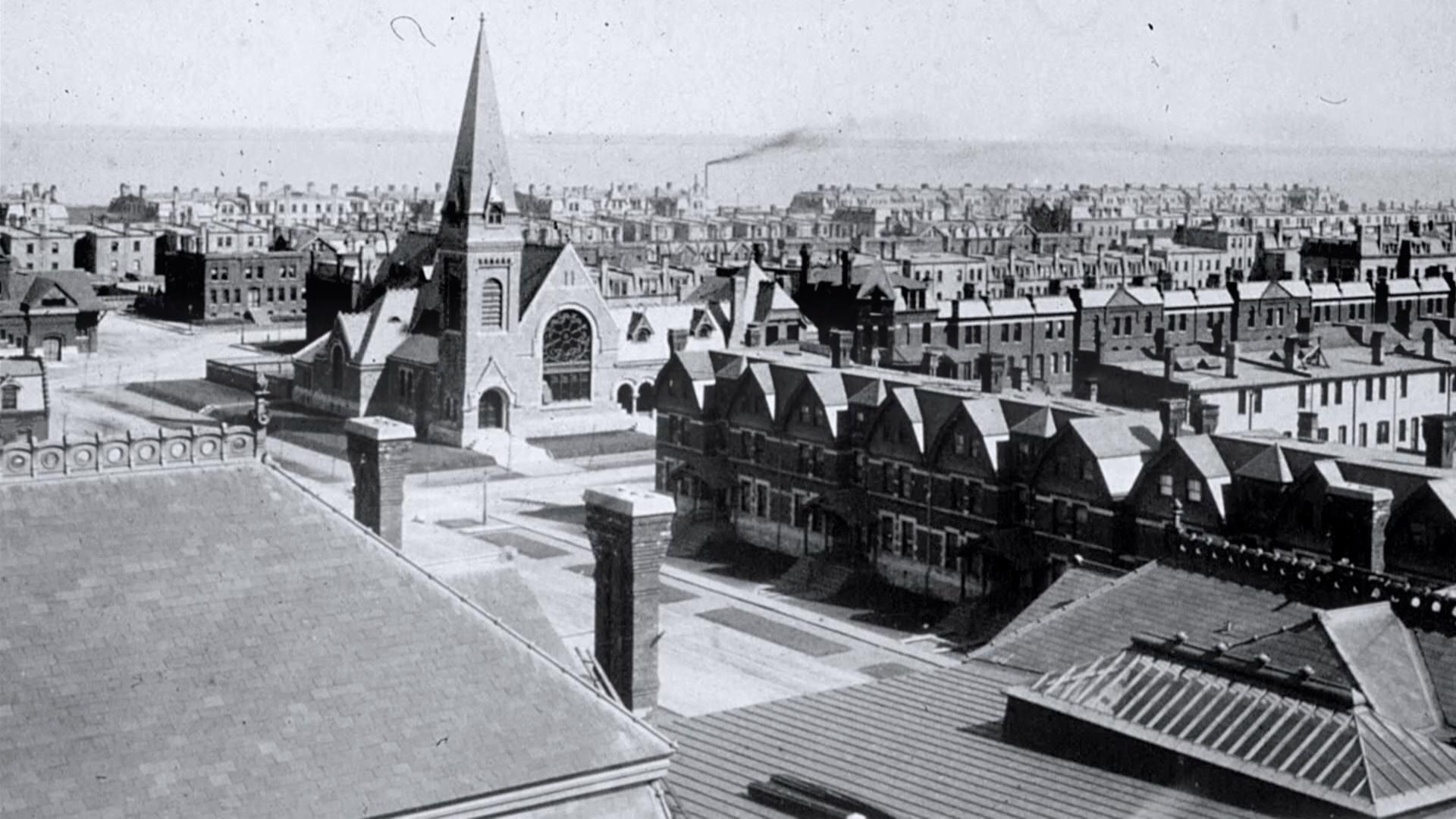

The buildings in the town were designed by architect Solon Spencer Beman, and landscape architect Nathan Franklin Barrett designed the streets and parks. The resulting town contained beautiful parkways and plazas, with such amenities as shops, a library, theater, schools, churches, and a hotel.

“This was not just an urban slum. This was meant to lift the spirits of his workers, and hopefully encourage the workforce to be loyal to the company and to be satisfied with their working conditions as well as their living conditions,” Bennett said.

Many of the red brick homes were in the Queen Anne style. There were tidy rowhomes with clean streets in the front and alleys in the back for trash. Some of the homes also had gas lighting and indoor plumbing – a luxury for the time. Cool breezes off the lake kept the homes cooler in warmer months.

The town, however, was not exempt from social and economic hierarchy. Workers higher up the chain lived in nicer, more spacious homes, while lower-wage workers had smaller homes or apartments.

“Pullman’s ideal of a class system was in some ways represented by what height ceiling [your home had],” Larry Spivack, president of the Illinois Labor History Society, told Chicago Stories. Top executives had homes with 12-foot ceilings, while foremen had 10-foot ceilings. Unskilled workers, Spivack said, had 8-foot ceilings.

The pristine living conditions came at a cost, which went right back into George Pullman’s pocket. According to the National Park Service, the rent that Pullman charged guaranteed him “a six percent return on the company’s investment in building the town.”

“He collected rent. He grew the food that people bought. The shopping center, the arcade, everything there went into the profit, including the church rent,” Spivack said.

Workers certainly could live in other towns or neighborhoods, but “there was this unwritten rule that those that were paying rent and living in the Pullman housing might be buffered a little bit from work slowdowns or work layoffs,” Bennett said.

And, apart from the town’s hotel bar where visitors could indulge, there was a ban on alcohol. Otherwise, drinking alcohol within town limits could get you instantly fired, according to Spivack.

“You are completely captured. You are free under law, but the social relations have really captured you in a cocoon where you don’t have much freedom to operate,” Bruno said. “[Pullman] very consciously crafted a workforce that he felt he could control. The idea behind a town that he constructs in his own name is really about control…any pushback on the part of the workers was viewed by him as a betrayal that was worthy of simply being dismissed.”

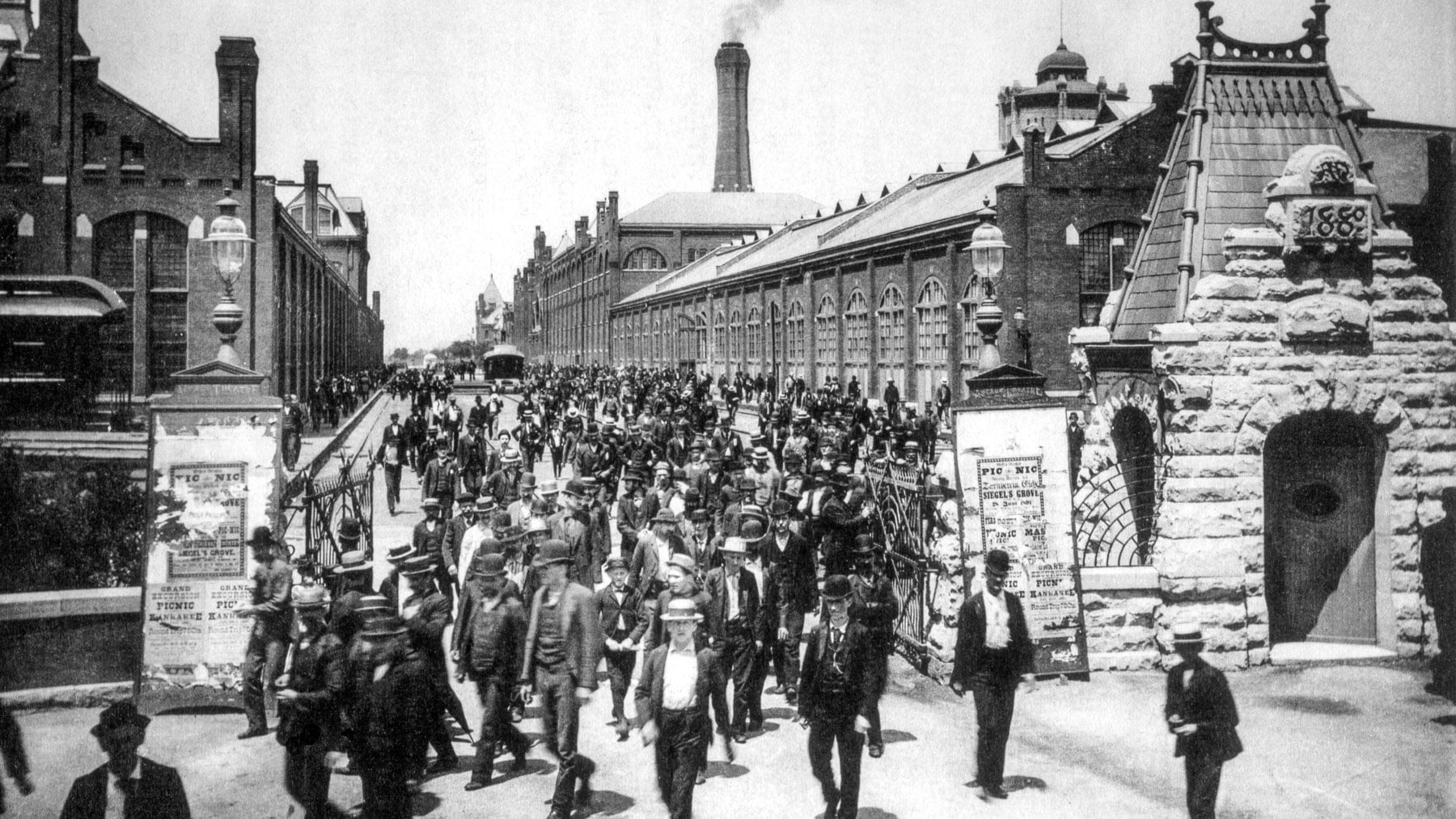

Amid the Panic of 1893 and the subsequent economic downtown, the patience of the town’s workers grew thin. The Pullman Company had cut hours and wages, but the rent for the town’s residents stayed the same. In 1894, the employees went on strike. The American Railway Union got involved, leading to a boycott of Pullman cars that brought most rail transport in the West and Midwest to a halt for a month. Violence escalated between strikers and police, and the strike ultimately failed to achieve the workers’ goals.

Two years after Pullman’s 1897 death, the town of Pullman was annexed to Chicago after the Illinois Supreme Court ordered the company to give up ownership of the town, arguing that the company’s charter stipulated it was only for manufacturing, and owning the town operated outside of that charter.

“Would a landlord today reduce rent if there was an economic depression?” Bennett said. “No. The difference here with the Pullman Company was the company was both the employer and the landlord, and that’s the business principle that got George Pullman the bad reputation and his legacy tarnished.”