George Pullman may have built a picturesque town outside Chicago for the workers who built his luxury sleeping train cars, but his paternalistic control over the lives of his employees helped spark one of the biggest and most contentious labor actions in American history. His company also relied on Black workers – most often porters and maids. Although those jobs helped establish a Black middle class, the workers endured racism and discrimination on the job. They, too, organized, and in doing so paved the way for the civil rights movement.

A Strike that Ground America to a Halt

At the end of 2022, President Joe Biden signed a bill that imposed a settlement upon railway companies and workers that had been brokered by his administration and then rejected by several of the rail unions for lacking enough paid leave. Under the 1926 Railway Labor Act, the federal government can offer recommendations in contract negotiations between rail companies and unions, as well as bind them to a labor agreement. The Biden Administration did both of those things in order to avoid a strike that Biden said would have caused “an economic catastrophe.”

For a sense of the possible effects of a railroad strike on the country, one can look back almost 130 years to one that originated just outside Chicago, in the town of Pullman.

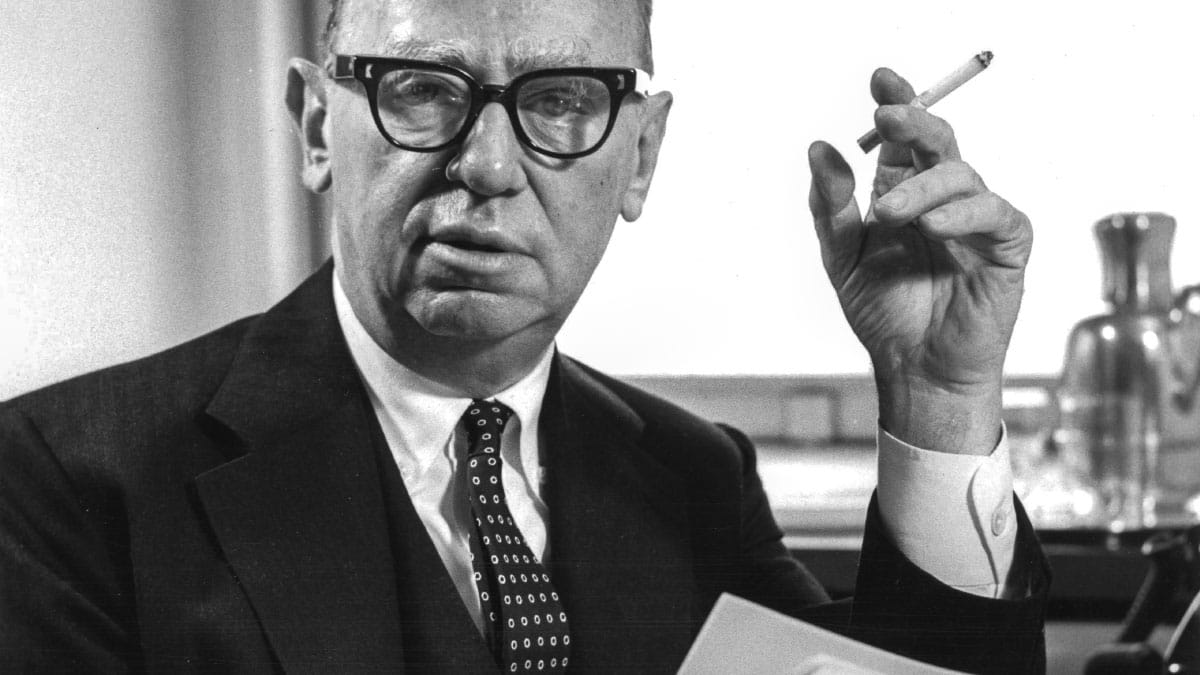

“Chicago is this boiling pot of conflict, hostility, uncertainty, and you really have the early formation of two warring classes: a powerful industrial capitalist class and a large polyglot of immigrant, Black, and White workers who are trying to make a claim on democratic citizenship. The battles that unfold will happen in all of the primary industries in and around Chicago,” Bob Bruno, professor of labor and employment relations at the University of Illinois, told Chicago Stories. “Railroads are central to that confrontation.”

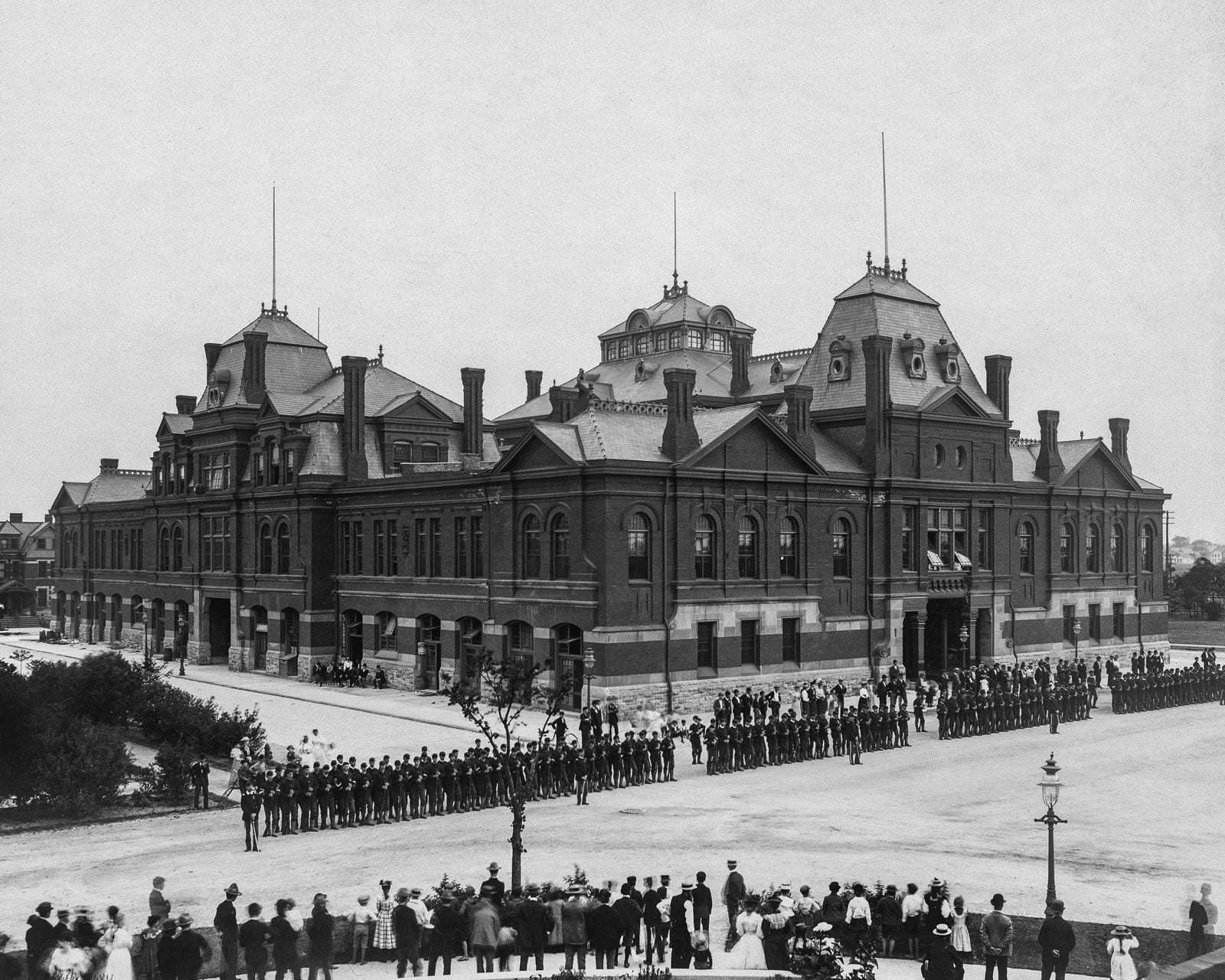

The town of Pullman, today a neighborhood within the city, was founded by George Pullman, a self-made titan of industry who started his career as a civil engineer but amassed a fortune after dreaming up a sleeping train car that allowed people to travel across the country in luxury. Pullman’s town was a model community compared to the crowded, dirty slums of the city in which many of the immigrant workers who built Pullman’s Palace Cars used to live.

But Pullman not only founded the town – he also owned it. The wages he paid the workers who lived there came back to the company in the form of rent and purchases at the town’s shops. “We are born in a Pullman house, fed from the Pullman shops, taught in the Pullman school, catechized in the Pullman Church, and when we die we shall go to the Pullman Hell,” one laborer said.

When an economic downturn came in 1893, Pullman cut wages. The rents his company charged the workers stayed the same, as did the price of the food and other goods they sold. In response, the Pullman workers called a strike in May 1894.

A month later, a meeting of the new American Railway Union (ARU) took place in Chicago, and, thanks to the testimony of such workers as Pullman seamstress Jennie Curtis, the ARU voted to boycott Pullman cars, refusing to move or handle them. Two hundred and fifty thousand workers joined the strike, which stopped trains on 29 railroads, halting most rail transport in the Midwest and West. It was one of the biggest labor actions in U.S. history. And it wasn’t just freight railroads; even commuter rail in the city came to a halt.

“Produce was lying to rot in the fields or in box cars,” Sue Bennett, assistant superintendent of the Pullman National Monument, told Chicago Stories. “People could not travel to funerals. Basically the economic engine came to a halt in the United States.”

As in 2022, the federal government eventually intervened – but without the Railway Labor Act, it had to come up with a pretext to do so. Because U.S. mail was transported on trains that sometimes contained Pullman cars and were thus stopped by the strike, rail managers accused the strikers of interfering in interstate commerce. The attorney general filed an injunction that declared the strike illegal.

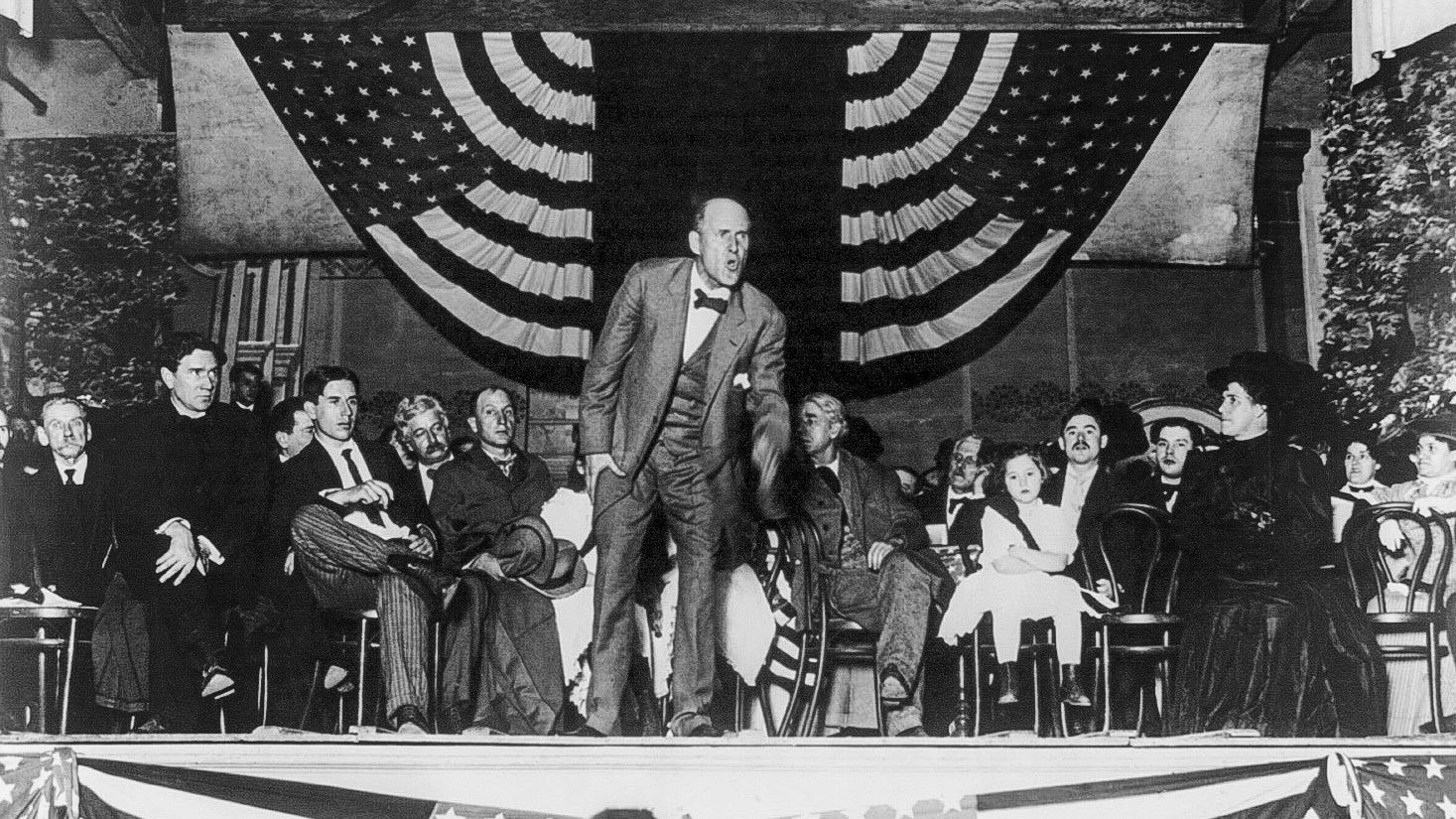

President Grover Cleveland deployed troops to end the strike. Violence broke out, resulting in dozens of deaths and thousands of injuries. The strike was defeated with no gains for the workers. The ARU’s head Eugene V. Debs – later a candidate of the Socialist Party of America for president of the United States – was arrested, along with seven other organizers. Despite the legal defense of a young Clarence Darrow, who later became a famed trial lawyer, they were sentenced to prison in a conviction upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court.

George Pullman died not long after the strike, having suffered a blow to his reputation. His company lost a bit more after his death, when the Illinois Supreme Court ordered it to sell off everything in the town except the factories. The company could no longer act as landlord to its workers.

There were still more battles to be waged between the company and its labor.

In Organizing, Black Workers Lay the Groundwork for the Civil Rights Movement

During its first meeting in Chicago, the ARU had voted by a very slim margin to prevent African American men from joining the union.

“They were just edged out of participating in the American Railway Union with Eugene Debs by a small number of votes, and so their voice was not heard,” Bennett said. “Their grievances were not part of this collective railing against the company for some relief.”

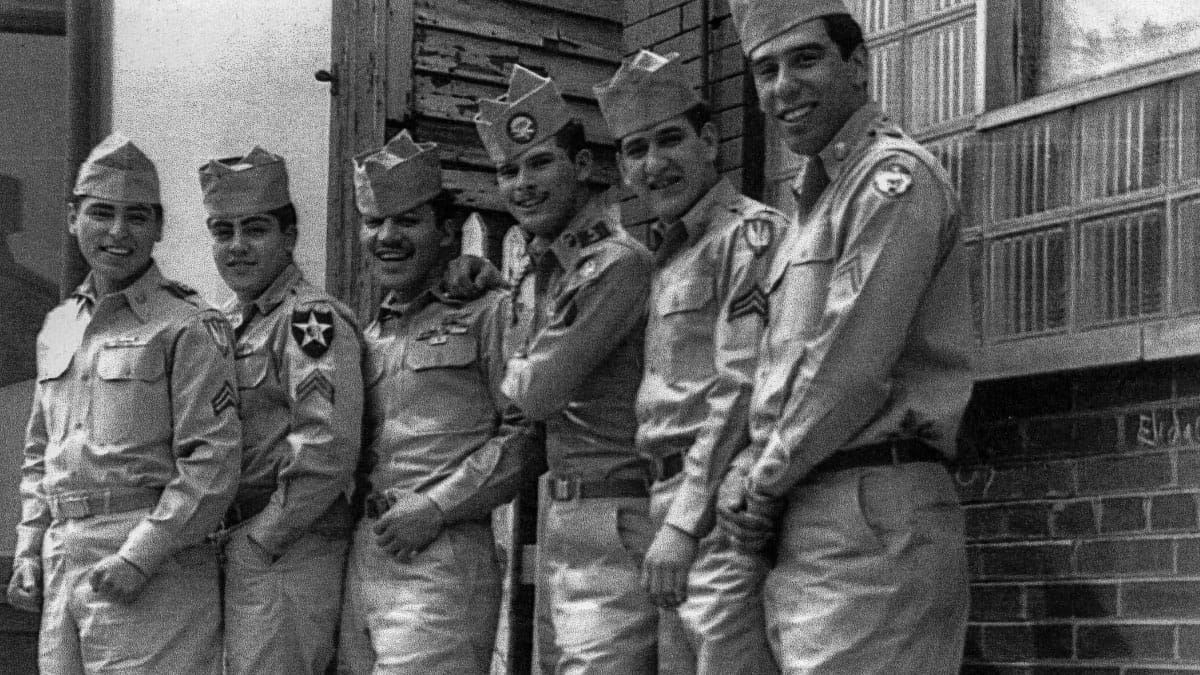

But the Pullman Company was a prominent employer of Black people: by the 1920s, it employed more Black workers than any other corporation in the country.

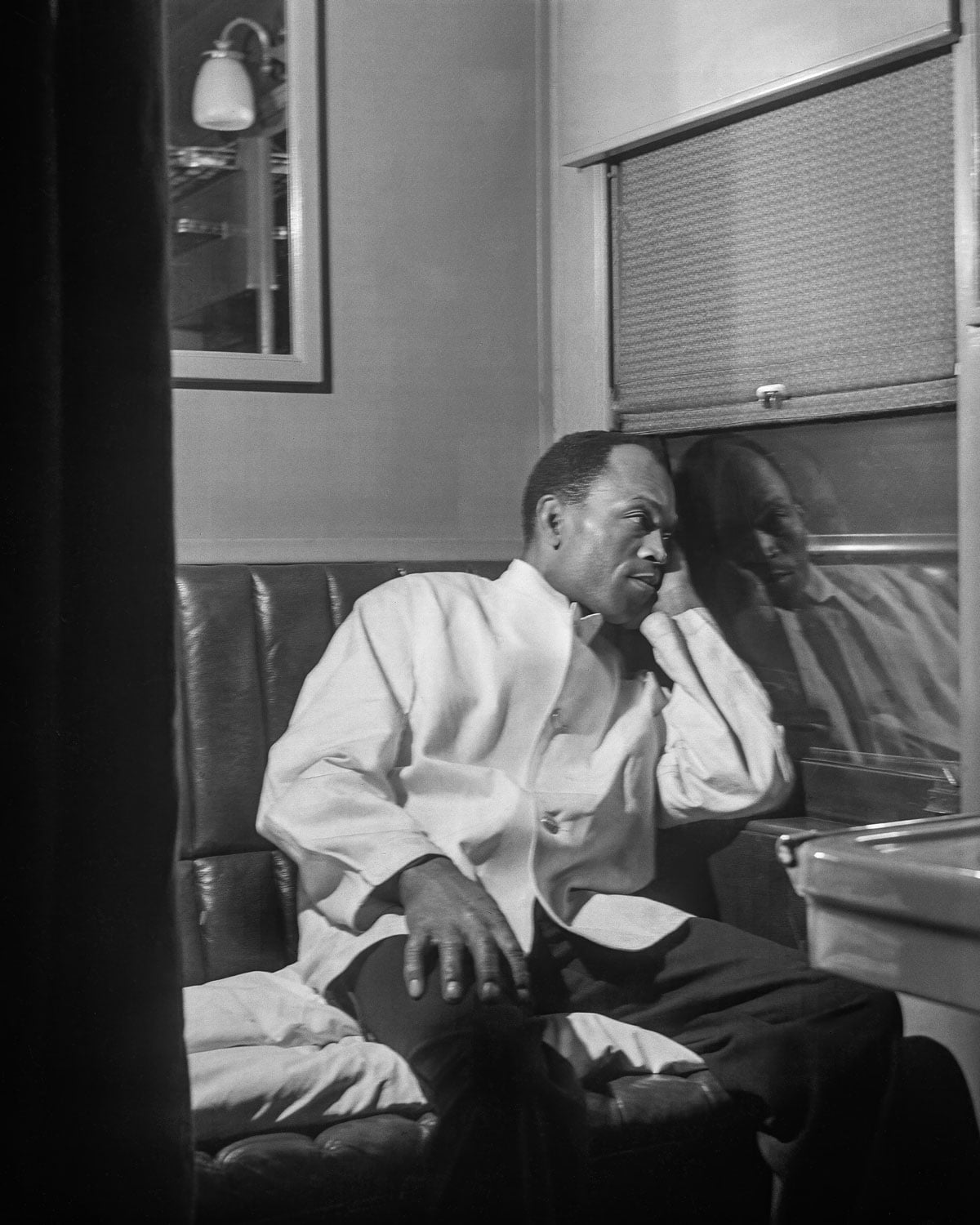

Most of those men worked as porters on the Palace Cars; Black women worked as maids. A job as a Pullman porter was respected and one of the better positions available to Black men at the time, allowing them to enter the Black middle class. Thurgood Marshall’s father was a porter, as were the parents or grandparents of Willie Brown, Whoopi Goldberg, and Michelle Obama, among others. The job allowed safe travel throughout the country, and porters often carried Black newspapers such as The Chicago Defender and The Pittsburgh Courier to Black people around the nation. Black Southerners were drawn north by the papers’ depictions of living and working conditions as well as jobs, helping to fuel the Great Migration to northern cities.

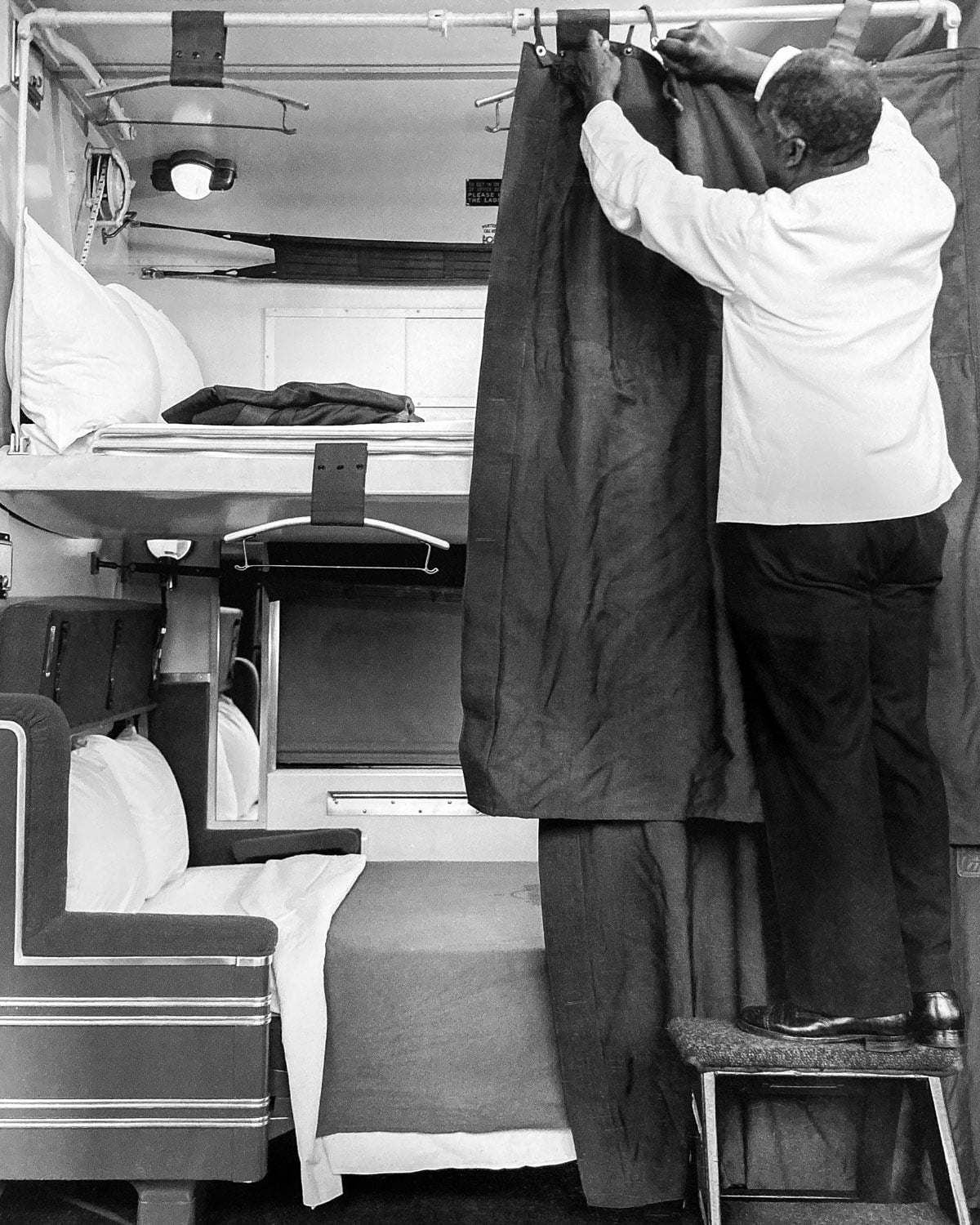

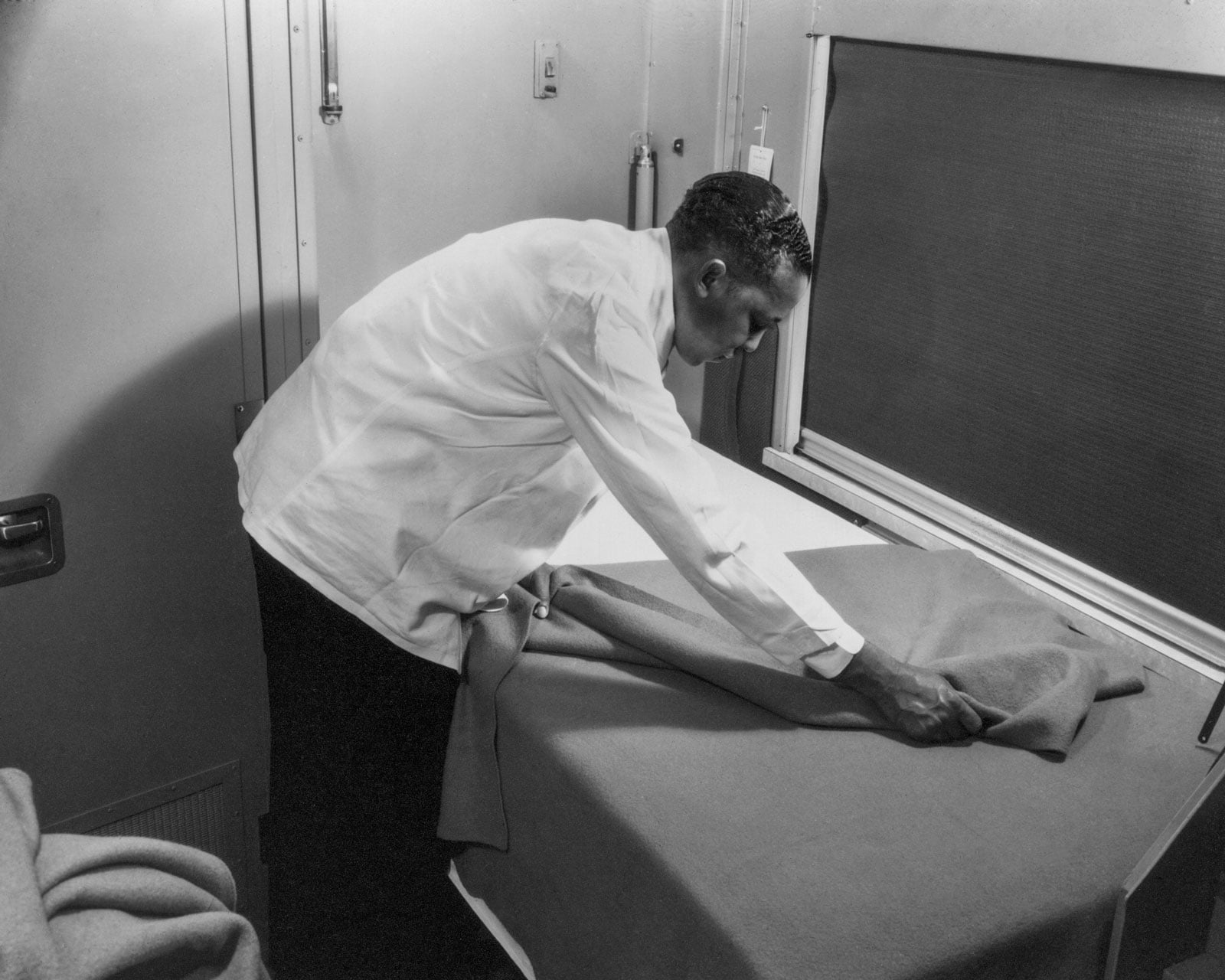

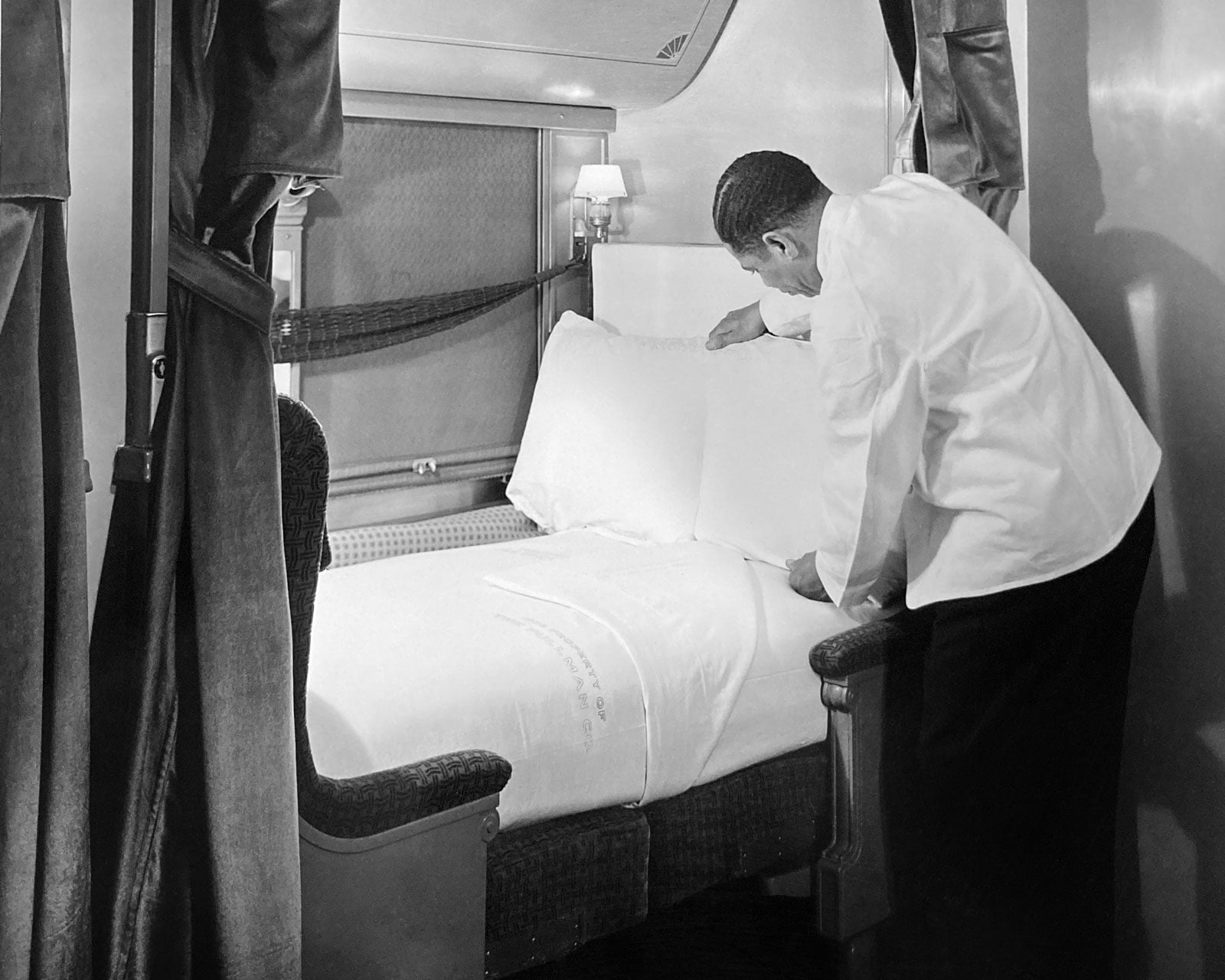

But there were obvious restrictions and denigrations. Porters worked long hours without breaks, and then could sometimes sleep for only a few hours at a time on a couch in the smoking car of the train. They often had to buy with their own money the shoeshine kits and towels required for the job. Their wages were low, although they could make decent money from tips – the potential of which allowed the company to pay them so little. And they often faced racism from the White customers whom they attended. A standard address for them was not their own name but “George,” after the founder of the company.

“There was a kind of dehumanizing component to that,” Cornelius L. Bynum, an assistant professor of history at Purdue University, told Chicago Stories. Bynum said the thinking at the time was “These weren’t skilled individuals, but…rote cogs who provided subservient service and did not need to be recognized as human beings or as individuals at all.”

The Pullman Porters

Many porters and maids were former enslaved people whom George Pullman thought would be deferential to his moneyed customers. Maids took care of children and helped traveling ladies with their wardrobe and hair, but there was often only one per train and only on deluxe or cross-country journeys.

As the workforce grew, porters began playing a role in promoting elements of Black culture, particularly through The Chicago Defender and The Pittsburgh Courier. In those papers were stories of Black workers standing up to their employers.

“Oftentimes they would have these newspapers and throw them off the back of the trains. And through word of mouth, local youth in particular would know where to pick these newspapers up, and they would take the papers back to their communities, back to their stores, back to their churches,” Lionel Kimble, associate professor of history at Chicago State University, told Chicago Stories.

Some porters soon began demanding more favorable conditions, including some of the rights that White Pullman workers had gained. The company tried to appease its Black workers with a company “union” that didn’t actually bargain on their behalf but instead offered social events. It also fired those who attempted to unionize outside the company union.

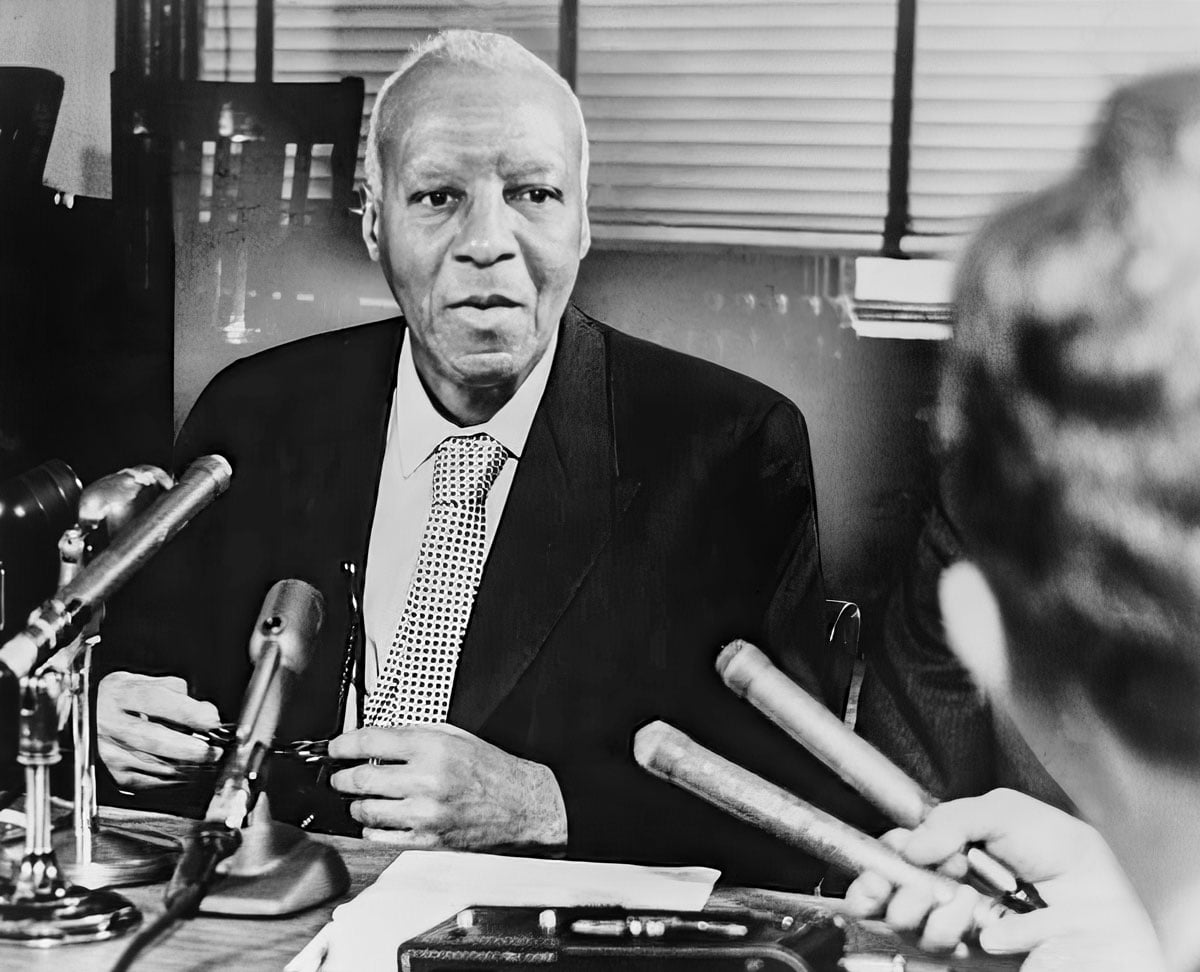

By 1925, the Pullman Company employed 12,000 Black men as porters. In that year, porters approached the awe-inspiring, stentorian-voiced A. Philip Randolph, the editor of a magazine circulated by porters that campaigned against lynching and advocated for Black participation in unions, to form a union of their own, and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was born.

“[Randolph] was a socialist. He definitely believed in the idea of class alliances and class identity and class consciousness,” Bruno said. “He saw the importance of being a free citizen, [of] being an independent American, not being controlled or dictated or limited by your skin color. He saw how that was deeply implicated with your economic power, your ability to protect your work.”

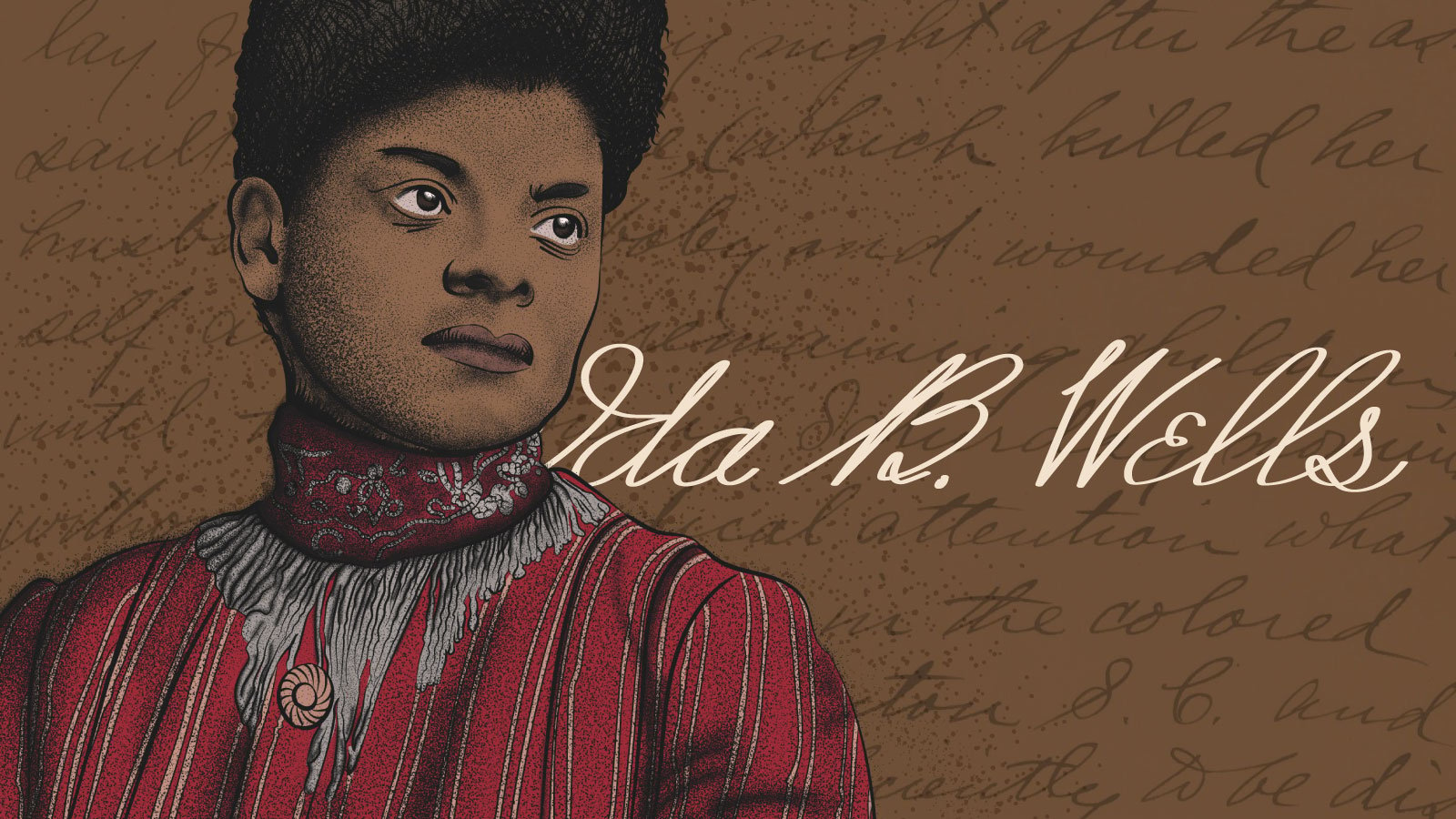

Pullman maids joined the union, while a “Ladies Auxiliary” of porters’ wives helped fundraise, host rallies, and educate others about the cause. Ida B. Wells helped gain the support of the Black community. The Brotherhood grew quickly, with its largest chapter in Chicago.

The Pullman Company did what it could to stop the union. It sent spies to meetings and fired workers who openly associated with the Brotherhood. It offered Randolph a blank check to cease his organizing, prompting his legendary reply: “Black people’s dignity is not for sale.” It refused to recognize the Brotherhood as legitimate, arguing that the company union took that role; the federal government refused to intervene on behalf of the Brotherhood’s appeals.

Similar tactics have been alleged against big companies resisting unionization efforts today. Approval of labor unions in the United States has climbed to its highest point since 1965, as workers at numerous large corporations – from Apple to Chipotle, Lowe’s, and Trader Joe’s – began pushing to organize during the disruptions of the COVID-19 pandemic. The National Labor Relations Board has charged companies such as Starbucks with labor law violations, with organizers alleging harassment, intimidation, illegal firing, and closure of unionized stores, claims that the company denies. Workers at a Staten Island Amazon warehouse organized the first union representing Amazon workers in 2022, despite a history of alleged union busting by the company.

But as the 2022 contract with rail workers by the government and the struggle of today’s unions to negotiate with their employers show, some workers still face an uphill battle.

That was true back when the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters first organized, as well. While the union struggled against Pullman’s anti-union tactics, the Great Depression began. Many Black Pullman workers were furloughed or lost their job, depriving the union of support.

It took the election of Franklin Delano Roosevelt as president of the United States and his passage of legislation that outlawed company unions and guaranteed collective bargaining rights for the Brotherhood to be officially recognized.

“This is where the Pullman porters really gained a considerable amount of power with the election of President Roosevelt, because now they were able to form a counter-union to these company unions and have the workers vote on who they wanted to represent them,” Kimble said.

In 1937, the Brotherhood signed an agreement for higher wages, a cap on monthly hours, and better job security on behalf of the porters, becoming the first Black union to successfully negotiate with a major company in the United States.

But that wasn’t the end of the Brotherhood and its influence. Porters brought their drive and organizational skill from the union to the civil rights movement. Former porter E. D. Nixon bailed Rosa Parks out of jail after she refused to give up her seat to a White passenger on a segregated bus in Montgomery, Alabama. He then helped organize the epochal bus boycott there, convincing Martin Luther King Jr. to join.

“Had it not been for A. Philip Randolph, we may not have seen a Martin Luther King,” Larry Spivack, president of the Illinois Labor History Society, told Chicago Stories. “A. Philip Randolph was really a mentor to Martin Luther King and helped him understand the power of sit-down strikes and boycotts, which translated into trying to end Jim Crow in the 1940s and ’50s and early ’60s.”

Randolph helped organize the famous March on Washington in 1963 and spoke at the Lincoln Memorial both before and after King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. Randolph received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Lyndon B. Johnson the following year, a few months after Johnson signed the era-defining Civil Rights Act.

The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters merged with another union in the 1970s, and the ensuing union still represents rail workers today. After the government’s imposition of a contract in 2022, it continued to negotiate with railroads, winning more paid sick leave for the workers.